16Th Century EDITIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

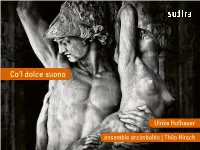

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara E Venezia Fall 2016

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara e Venezia Fall 2016 Monday, 17 October 6.00pm Italian Madrigals of the Late Cinquecento Performers: Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Dolci miei sospiri tra Ferrara e Venezia Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) for his assistance in planning this concert. Program Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1580-1651), Toccata seconda arpeggiata da: Libro primo d'intavolatura di chitarone, Venezia: Antonio Pfender, 1604 Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Voi partite mio sole da: Primo libro d'arie musicali, Firenze: Landini, 1630 Claudio Monteverdi Ecco mormorar l'onde da: Il secondo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardane, 1590 Concerto di Margherita Giovanni de Macque (1550-1614), Seconde Stravaganze, ca. 1610. Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Luzzasco Luzzaschi (ca. 1545-1607), Aura soave; Stral pungente d'amore; T'amo mia vita Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba da: Madrigali per cantare et sonare a uno, e due e tre soprani, Roma: Verovio, 1601 Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1463), T'amo mia vita da: Il quinto libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Amadino, 1605 Luzzasco Luzzaschi Canzon decima a 4 da: AAVV, Canzoni per sonare con ogni sorte di stromenti, Venezia: Raveri, 1608 We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff Giaches de Wert (1535-1596), O Primavera gioventù dell'anno (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) da: L'undecimo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardano, 1595 for his assistance in planning this concert. -

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

Direction 2. Ile Fantaisies

CD I Josquin DESPREZ 1. Nymphes des bois Josquin Desprez 4’46 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 2. Ile Fantaisies Josquin Desprez 2’49 Ensemble Leones Baptiste Romain: fiddle Elisabeth Rumsey: viola d’arco Uri Smilansky: viola d’arco Marc Lewon: direction 3. Illibata dei Virgo a 5 Josquin Desprez 8’48 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 4. Allégez moy a 6 Josquin Desprez 1’07 5. Faulte d’argent a 5 Josquin Desprez 2’06 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction 6. La Spagna Josquin Desprez 2’50 Syntagma Amici Elsa Frank & Jérémie Papasergio: shawms Simen Van Mechelen: trombone Patrick Denecker & Bernhard Stilz: crumhorns 7. El Grillo Josquin Desprez 1’36 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction Missa Lesse faire a mi: Josquin Desprez 8. Sanctus 7’22 9. Agnus Dei 4’39 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 10. Mille regretz Josquin Desprez 2’03 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 11. Mille regretz Luys de Narvaez 2’20 Rolf Lislevand: vihuela 2: © CHRISTOPHORUS, CHR 77348 5 & 7: © HARMONIA MUNDI, HMC 901279 102 ITALY: Secular music (from the Frottole to the Madrigal) 12. Giù per la mala via (Lauda) Anonymous 6’53 EnsembleDaedalus Roberto Festa: direction 13. Spero haver felice (Frottola) Anonymous 2’24 Giovanne tutte siano (Frottola) Vincent Bouchot: baritone Frédéric Martin: lira da braccio 14. Fammi una gratia amore Heinrich Isaac 4’36 15. Donna di dentro Heinrich Isaac 1’49 16. Quis dabit capiti meo aquam? Heinrich Isaac 5’06 Capilla Flamenca Dirk Snellings: direction 17. Cor mio volunturioso (Strambotto) Anonymous 4’50 Ensemble Daedalus Roberto Festa: direction 18. -

PETRUCCI E-02 TIBALDI 15-04-2005 09:20 Pagina 491

PETRUCCI E-02 TIBALDI 15-04-2005 09:20 Pagina 491 RODOBALDO TIBALDI REPERTORIO TRÀDITO E COEVO NELLE INTAVOLATURE PER CANTO E LIUTO RACCOLTE DA FRANCESCO BOSSINENSIS CON UNO SGUARDO ALLE RACCOLTE ANALOGHE I due libri di intavolature per canto e liuto raccolti da Franciscus Bossinensis e pubblicati da Ottaviano Petrucci nel 1509 e nel 1511 sono stati variamente conside- rati dagli studi musicologici, talvolta in riferimento alla prassi esecutiva, talvolta con una certa attenzione a singoli e ben determinati fenomeni analizzati in alcuni brani, ma più spesso come riduzioni a tre parti di componimenti ‘vocali’ a quattro voci (o comunque concepiti a quattro voci); il più delle volte, comunque, vengono esamina- ti come un qualcosa esistente in quanto dipendente dai libri di frottole editi tra il 1504 e il 1514, e non nella loro autonomia. Eppure, uno sguardo complessivo alle due sil- logi, alla mappa delle relazioni con i testimoni a penna e a stampa afferenti al mede- simo repertorio (tra i quali un posto non secondario ricopre l’importante manoscrit- to Parigi, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Rés. Vmd. ms 27), il confronto tra le diverse versioni, che talvolta rivela alcuni aspetti interessanti riguardanti non solo la sfera dell’esecuzione, ma soprattutto quella della composizione (o, per lo meno, sembra talvolta che la diversa destinazione delle raccolte del Bossinensis sia consi- derata proprio nella sua ‘alterità’), ed infine il numero degli unica conservati nei due libri, e nel secondo in modo particolare, ci permettono di osservarli in una prospetti- va un poco diversa, forse anche a causa della perdita del decimo libro di frottole. -

The Collegium Musicum the Madrigal Singers

The School ofMusic , presents the 57th program ofthe 1989-90 season c,'19qO 2. -2-7 The Collegium Musicum Margriet Tmdemans, Director The Madrigal Singers Joan Catoni Conlon. Director .. '..,-' ' "LaBella Venezia" Diversity of styles from La Serenissima February 27, 1990, 8:00 PM Meany 1beater " I -- --......~. r' I D~lI,(001 c fk.s 'fF Ir t9 0 2 11.(,,;03 Thus. amidst her angry tears, she lifted her voice to heaven. In this way in the hearts oflovers does Love Program mixflames and ice. Ca.~"'7*1lr(&02A Cynthia Beiunen. mezzo-soprano Dessus Ie marebe d'Arras (1528) .......... ADRIAN WIU.AERT (C.1490-1562) At the market (me"ily. merrily we play). I encountered a Spaniard (merrily ...). He said, 'Usten. maid,' Hor care canzonette (1584) ......................•CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI (merrily...) 'I will give you silver' (merrily...). Dear camonets. go swiftly and surely. Ricercar declmo (Venice. 1559) ................................WILLAERT without saying a word. to Idss her hand... r Sweet camonets. go only to one...begging her pardon... Maledetto (1632) .................................CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI Adoramus te (1620) ....................CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI (1567-1643) (Lament ofOlympia. abandoned by her lover on a We adore you. 0 Christ. and we bless'JOu./Or by your desert island}Cursed one! I love with afaitlt/ul. burn.ing passion. priceless blood, you have redeemed us. Have mercy upon yet I am a river oftorment. Love's ~ows pierce us. me. yet I am disarmed. You dismiss the fire ofmy love! Laurie Hungerford Flint, soprano Cantate Domino (1620) ........................... CI..AUDIO MONTEVERDI Sing to the Lord a new song. a bless G04 s name, who has made miracles to happen. -

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker July 8-15, and July 15-22 Connecticut College, New London CT Music of France and the Low Countries Largest recorder program in U.S. Expanded vocal programs Renaissance reeds and brass New London Assembly Festival Concert Series Historical Dance Viol Excelsior www.amherstearlymusic.org Amherst Early Music Festival 2018 Week 1: July 8-15 Week 2: July 15-22 Voice, recorder, viol, violin, cello, lute, Voice, recorder, viol, Renaissance reeds Renaissance reeds, flute, oboe, bassoon, and brass, flute, harpsichord, frame drum, harpsichord, historical dance early notation, New London Assembly Special Auditioned Programs Special Auditioned Programs (see website) (see website) Baroque Academy & Opera Roman de Fauvel Medieval Project Advanced Recorder Intensive Ensemble Singing Intensive Choral Workshop Virtuoso Recorder Seminar AMHERST EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL FACULTY CENTRAL PROGRAM The Central Program is our largest and most flexible program, with over 100 students each week. RECORDER VIOL AND VIELLE BAROQUE BASSOON* Tom Beets** Nathan Bontrager Wouter Verschuren It offers a wide variety of classes for most early instruments, voice, and historical dance. Play in a Letitia Berlin Sarah Cunningham* PERCUSSION** consort, sing music by a favorite composer, read from early notation, dance a minuet, or begin a Frances Blaker Shira Kammen** Glen Velez** new instrument. Questions? Call us at (781)488-3337. Check www.amherstearlymusic.org for Deborah Booth* Heather Miller Lardin* Karen Cook** Loren Ludwig VOICE AND THEATER a full list of classes by May 15. Saskia Coolen* Paolo Pandolfo* Benjamin Bagby** Maria Diez-Canedo* John Mark Rozendaal** Michael Barrett** New to the Festival? Fear not! Our open and inviting atmosphere will make you feel at home Eric Haas* Mary Springfels** Stephen Biegner* right away. -

Taverner Byrd

TAVERNERMASSES BY BYRD WITH MOTETS BY &&STRAVINSKY& DURUFLÉ The Ripieno Choir 7.30 pm Saturday Tickets £15 in advance, conducted by 25 June 2016 £17 on the day, David Hansell All Saints’ Church £5 for under-18s. Call Weston Green 020 8399 2714 or email Esher, Surrey [email protected] KT10 8JL – or book online at 25 JUNE ripienochoir.org.uk RIPIENOthe choır. JOHN TAVERNER (c1490-1545) Western Wynde Mass WILLIAM BYRD (c1540-1623) Mass for Four Voices interspersed with motets by IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) Ave Maria & Pater noster MAURICE DURUFLÉ (1902-1986) Four motets on Gregorian melodies & Notre Père Four great composers and unrelentingly TAVERNER brilliant music in strongly contrasting styles. Taverner’s Western Wynde Mass is a BYRD set of variations in which the folk song theme moves through the choral texture & surrounded by ever-inventive and intricate counter-melodies. The result is an intriguing mix of medieval, Eton Choirbook and later Renaissance effects which never fails to captivate singers and listeners alike. Byrd modelled his famous Mass for Four Voices on Taverner’s Mean Mass, quoting from it in 25 JUNE his own Sanctus movement. This famous work has not been sung by Ripieno for several years and we The concert will start at are especially looking forward to the Agnus Dei 7.30pm and will end movement – some of music history’s greatest pages. at approximately 9.30pm. In contrast to the intricate polyphony of Tickets: £15 in advance, the sixteenth century, the twentieth century motets £17 on the day, £5 for use simple chordal textures that are positively under-18s, from the box austere by comparison, anticipating Arvo Pärt and office: 020 8399 2714, or John Tavener. -

Some Historical Perspectives on the Monteverdi Vespers

CHAPTER V SOME HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE MONTEVERDI VESPERS It is one of the paradoxes of musicological research that we generally be- come acquainted with a period, a repertoire, or a style through recognized masterworks that are tacitly or expressly assumed to be representative, Yet a masterpiece, by definition, is unrepresentative, unusual, and beyond the scope of ordinary musical activity. A more thorough and realistic knowledge of music history must come from a broader and deeper ac- quaintance with its constituent elements than is provided by a limited quan- tity of exceptional composers and works. Such an expansion of the range of our historical research has the advan- tage not only of enhancing our understanding of a given topic, but also of supplying the basis for comparison among those works and artists who have faded into obscurity and the few composers and masterpieces that have sur- vived to become the primary focus of our attention today. Only in relation to lesser efforts can we fully comprehend the qualities that raise the master- piece above the common level. Only by comparison can we learn to what degree the master composer has rooted his creation in contemporary cur- rents, or conversely, to what extent original ideas and techniques are re- sponsible for its special features. Similarly, it is only by means of broader investigations that we can detect what specific historical influence the mas- terwork has had upon contemporaries and younger colleagues, and thereby arrive at judgments about the historical significance of the master com- poser. Despite the obvious importance of systematic comparative studies, our comprehension of many a masterpiece stiIl derives mostly from the artifact itself, resulting inevitably in an incomplete and distorted perspective. -

May 2012 Broadside

T H E A T L A N T A E A R L Y M U S I C A L L I A N C E B R O A D S I D E Volume XII, # 4 May/June 2012 President’s Message Parting and new Board members As we near the end of our 2011-2012 year, we give our thanks to our parting Board members, Jane Burke and George Lucktenberg. Jane has served you organization for 6 years as Board member and membership chair and in many other ways so necessary for an organization. George has also served on the Board representing harpsichordists and their interests. (The bylaws of AEMA limit Board membership to two 3-year terms). We now welcome our new Board members, Brenda Lloyd and Daniel Pyle. You may recall their candidate statements enclosed with the recent ballots. Brenda has already worked with us, behind the scenes, in editing our BROADSIDE newsletters, a truly appreciated service. Daniel will join us with his treasured experience with so many aspects of Early music. AEMA MISSION It is the mission of the Atlanta Early Music Alli- ance to foster enjoyment State of AEMA and awareness of the his- torically informed perform- On May 12th we held our Annual Membership meeting, hosted by David Buice at the ance of music, with special emphasis on music written Presbyterian Church of the New Covenant. We enjoyed the potluck luncheon and finished with a before 1800. Its mission will music session in the lovely sanctuary under the leadership of Robert Bolyard.