Are You Man Enough?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

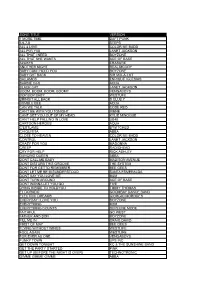

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Pop Stars RE ORDER 17/10/02 3:05 PM Page 2

Pop Stars RE ORDER 17/10/02 3:05 PM Page 2 Pop Stars Series EZP-07 EZP-10 Duets Vol 1 Hits Of Kylie Vol 1 1) You’re The One That I Want Grease 1) Can’t Get You Outta My Head 2) I Got You Babe Chrissie Hinde & UB40 2) Spinning Around 3) Pure & Simple Hear’ say 3) On A Night Like This 4) Up Where We Belong Joe Cocker & Jennifer Warnes 4) The Loco-motion 5) I’ll Be Missing You Puff Daddy & Faith Evans 5) I Should Be So Lucky 6) Endless Love Lionel Richie & Diana Ross 6) Fever 7) Don’t Go Breaking My Heart Elton John & Kiki Dee 7) Kids (duet with Robbie Williams) 8) I Know Him So Well Elaine Paige & Barbara Dickson 8) Got To Be Certain DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES EZP-08 EZP-11 Hits Of Steps Hits Of westlife 1) Tragedy 1) Flying Without Wings 2) Summer Of Love 2) I Have A Dream 3) Say You’ll Be Mine 3) If I Let You Go 4) One For Sorrow 4) Queen Of My Heart 5) Love’s Got A Hold On My Heart 5) Swear It Again 6) Deeper Shade Of Blue 6) Uptown Girl 7) Better Best Forgotten 7) What Makes A Man 8) After The Love Has Gone 8) When You’re Looking Like That DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES EZP-09 EZP-12 Rock & Roll Xmas Hits Of S Club The No1 Christmas Seller 1) Merry Christmas Everybody Slade 1) You 2) I Wish It Could Be Christmas Wizzard 2) Bring It All Back 3) Last Christmas Wham 3) Have You Ever 4) Wombling Merry Christmas The Wombles 4) Don't Stop Movin' 5) A Spaceman Came Travelling Chris De Burgh 5) S Club Party 6) When A Child Is Born Johnny Mathis 6) You're My Number One 7) Merry Christmas Everyone Shakin Stevens 7) Two In A Million 8) Do They Know Its Christmas Band Aid 8) Never Had A Dream Come True 9) (New Year Countdown) Auld Lang Syne 9) Natural 10)Reach DISC HAS REPEATED TRACKS WITH VOCAL GUIDES www.easykaraoke.com ©. -

RADIO and TELEVISION MIRROR, Published Monthly by MACFADDEN PUBLICATIONS, INC., Washington and South Avenues, Dunellen, New Jersey

10* The Favorite of Millions of Listeners BIG SISTER Now as a ROMANTIC NOVEL ve pages f (5pec.Sl star po?tra.ts - Stella Dallas and Front Page Farrell WHISPER "I LOVE YOU" ^^^ W,TH Perfume, Face Powder, Lipstick, Talcum, Single toosePow- JCOfl der Vanity *» ZZVWaaaA YOUR STAR IS LUCKY., if your Smile is Right! Your smile is YOU! Help keep your But remember healthy gums are impor- Ipana is specially designed not only to gums firmer, your teeth brighter tant if you want your smile to have clean teeth brilliantly and thoroughly with Ipana and massage! brightness and sparkle. That's why it's but, with massage, to help firm and so unwise ever to ignore the first warn- strengthen your gums. Massage a little YOU don't have to be a beauty to have ing tinge of "pink" on your tooth brush. extra Ipana onto your gums every time beauty's rewards — popularity, suc- you brush your teeth. Notice its clean Tooth cess, the man you want most to win. Never ignore "Pink Brush" and refreshing taste. That invigorating Even if you're "plain" let your hopes If you see "pink" on your tooth brush "tang" means circulation is quickening in tissues—helping soar high. Fortune can be more than ...see your dentist. He may merely say gum gums to health- ier firmness. kind . fortune can be lavish if your your gums have become tender because smile is right! A lovely smile is a mag- today's soft foods have robbed them of Get a tube of economical Ipana Tooth net to others . -

Speak to a Girl!

Speak to a Girl! Count: 32 Wall: 2 Level: Upper Intermediate Choreographer: Stephen Paterson, April 2017, Version 1 Music: Tim McGraw & Faith Hill - Speak To A Girl (iTunes) 3.52 | 52 bpm Notes: 8 count intro from the start of the song. Start on the lyrics – “Damn” (Two TAGS, first after wall 2, second after wall 4) [1-8] Behind, Slow Sweep, Rock Back, Recover, 1/4, 1/2, Slow Sweep, Across, Back, Back, Across, Back, 1/4,Touch, Slow 1/4 Pivot, Rock Back, Recover, Pivot 1/2, Full Turn 1 & a Step L slightly behind R, slow sweep R to side (& a) 2 & a Rock step R slightly behind L, Recover weight onto L in place (&), turn 1/4 L then step R back (a) (9.00) 3 & a Turn 1/2 L then step L fwd, slow sweep R side then forward (&a) (3.00) 4 & a Step R across L, Step L back (&), Step R back (a) 5 & a Step L across R, Step R back (&), Turn 1/4 L then step L out to side (a) (12.00) 6 & a Touch ball of R across L, unwind 1/4 L (&), take weight onto R in place (a) (9.00) 7 & a Rock step L back, Recover weight onto R in place (&), Step L fwd (a) 8 & a Pivot 1/2 R taking weight onto R in place, Turn 1/2 R then step L back (&), Turn 1/2 R then step R fwd (a) (3.00) [9-16] Across, Rock Side, Recover, Across, 1/4 Back, Step Side, Across, Rock Side, Recover, Across, 1/4 Back, Step Side Step Forward, Slow 1/2 Pivot, 1/2 Back, Sweep, Rock Back, Recover, Left Full Turn, Right Full Turn 1 & a Step L across R, Rock R out to side (&), recover weight onto L in place (a) 2 & a Step R across L, Turn 1/4 R then step L back (&), Step R out to side (a) (6.00) 3 & a Step -

Placebo Greatest Hits Zip

Placebo greatest hits zip click here to download Placebo - Greatest Hits () [2CD] [ Kbps] [MEGA]. Disco 1. For What It's Worth Meds Every You Every Me Battle For The Sun Because I Want You. Download www.doorway.ru Direct Link Download. Download www.doorway.ru Mediafire Download. Free download info for the Indie rock Alternative rock album Placebo - Greatest Hits () compressed www.doorway.ru file format. The genre category. Download Placebo Greatest Hits es una banda de rock alternativo formada en en Londres, Inglaterra. Está compuesta por Brian Molko y. Placebo - Greatest Hits (2CD) free download Title Of Album: Placebo - Greatest Hits www.doorway.ru www.doorway.ru().zip. August www.doorway.ru().zip www.doorway.ru www.doorway.ru().zip, light up for sketchup. Placebo - Greatest Hits () Year: | 2CD | Format: MP3 | Bitrate: kbps | MB Genre Placebo - Greatest Hits ().zip - [Verified Download]. Free Full Download Placebo Greatest Hits rapidshare megaupload hotfile, Placebo Greatest Hits via torrent download, rar Zip password mediafire included. unlock,apple,www.doorway.ru,Miss,Rita,Episode,3,Pdf,www.doorway.ru().zip,dota,2,chest,unlocker,password,consumer,tribes,cova,,bernard,|,kozinets. Greatest Hell's Hits () CD 1: CD 2: Bryan Adams - The Best Of Me. Placebo - Greatest Hits () CD 1. Todos os livros da casa do www.doorway.ru. placebo. e4f8 Generally WinZip program was created back in , while the ZIP format was created in ,. Placebo Greatest Hits () (Al.R) download. Greatest Hits. CD1. For What It's Worth. Meds. Every You Every Me. Battle For The Sun. Because I Want You. Find a Placebo - Greatest Hits first pressing or reissue. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

The Dialogical Relationship Between Spiritual and Professional Identity in Beginning Teachers: Context, Choices and Consequences

The dialogical relationship between spiritual and professional identity in beginning teachers: context, choices and consequences by Kimberly Franklin B.Ed. UBC 1985 M.Ed. OISE 1989 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION In the Faculty of Education © Franklin 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

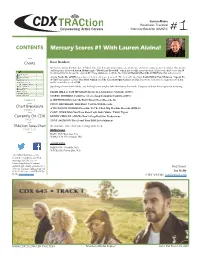

Mercury Scores #1 with Lauren Alaina!

Lauren Alaina Road Less Traveled Mercury Records (UMGN) CONTENTS Mercury Scores #1 With Lauren Alaina! — Charts Dear Readers; Spring has sprung big-time here in Music City which means temperatures are on the rise and so are many great new singles. One to note and brag on is the new Lauren Alaina single “Road Less Traveled” which has steadily risen our chart. It has been chart active for 34 weeks and this week tops the chart at #1! Congratulations to all the fine folks atMercury Records (UMGN) for this achievement. Arista Nashville (SMN) has a lot to celebrate this week as well. The new offering from Faith Hill & Tim McGraw “Speak To A Girl” has garnered both The Most Added and The Greatest Spin Gainer awards this week. It is also the highest new debut on the chart this week at #44. Speaking of new chart debuts...we had eight new singles take their bows this week. Congrats to these fine singles for debuting... FAITH HILL & TIM MCGRAW/Speak To A Girl/Arista Nashville (SMN) MAREN MORRIS/I Could Use A Love Song/Columbia Nashville (SMN) PAGE 2-4 GARTH BROOKS/Ask Me How I Know/Pearl Records Inc. — SWON BROTHERS, THE/Don’t Call Me/TSB Records Chart Breakouts A THOUSAND HORSES/Preachin’ To The Choir/Big Machine Records (BMLG) PAGE 6-7 — CODY JINKS/Wish You Were Here/Cody Jinks Music / Thirty Tigers Currently On CDX DENNY STRICKLAND/We Don’t Sleep/Red Star Productions PAGE 7 TONY JACKSON/The Grand Tour/DDS Entertainment — TRACtion Texas Chart We announce some chart panel changes this week.