Robert Schumann Robert Schumann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1785-1998 September 1998

THE EVOLUTION OF THE BROADWOOD GRAND PIANO 1785-1998 by Alastair Laurence DPhil. University of York Department of Music September 1998 Broadwood Grand Piano of 1801 (Finchcocks Collection, Goudhurst, Kent) Abstract: The Evolution of the Broadwood Grand Piano, 1785-1998 This dissertation describes the way in which one company's product - the grand piano - evolved over a period of two hundred and thirteen years. The account begins by tracing the origins of the English grand, then proceeds with a description of the earliest surviving models by Broadwood, dating from the late eighteenth century. Next follows an examination of John Broadwood and Sons' piano production methods in London during the early nineteenth century, and the transition from small-scale workshop to large factory is noted. The dissertation then proceeds to record in detail the many small changes to grand design which took place as the nineteenth century progressed, ranging from the extension of the keyboard compass, to the introduction of novel technical features such as the famous Broadwood barless steel frame. The dissertation concludes by charting the survival of the Broadwood grand piano since 1914, and records the numerous difficulties which have faced the long-established company during the present century. The unique feature of this dissertation is the way in which much of the information it contains has been collected as a result of the writer's own practical involvement in piano making, tuning and restoring over a period of thirty years; he has had the opportunity to examine many different kinds of Broadwood grand from a variety of historical periods. -

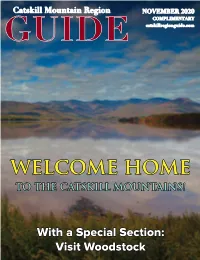

NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE Catskillregionguide.Com

Catskill Mountain Region NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! With a Special Section: Visit Woodstock November 2020 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com IN THIS ISSUE www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 35, NUMBER 11 November 2020 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS & ARTISTS Benedetta Barbaro, Darla Bjork, Rita Gentile, Liz Innvar, Joan Oldknow, Jeff Senterman, Sarah Taft, Margaret Donsbach Tomlinson & Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee On the cover: The Ashokan Reservoir. Photo by Fran Driscoll, francisxdriscoll.com Justin McGowan & Emily Morse PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 A CATSKILLS WELCOME TO THE GRAF PIANO DISTRIBUTION By Joan Oldknow & Sarah Taft Catskill Mountain Foundation 12 ART & POETRY BY RITA GENTILE EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: November 10 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year 13 TODAY BUILDS TOMORROW: by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box How to Build the Future We Want: The Fear Factor 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ By Robert Tomlinson catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines 14 VISIT WOODSTOCK send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! or occupied by the error. -

Tobias Koch Pianist

TOBIAS KOCH PIANIST TERMINE 2013 13.-15. Januar 2013 BAYREUTH 17. Januar 2013 BR Klassik Radiosendung 15.05-16 Uhr Einstündige Sendung in der Reihe "Pour le Piano - Tastenspiele" mit Tobias Koch. Werke von Ferdinand Hiller, Franz Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann und Mozart. 17.-23. Januar 2013 MÜNCHEN BR-Produktion mit Werken von Richard Wagner: Klaviersonaten, Lieder und Faust-Gesänge. Koproduktion mit cpo. 19. Januar 2013 MÜNCHEN BR Studio 1 im Funkhaus, 20 Uhr "Der frühe Wagner". Extra-Konzert im BR mit Klaviermusik und Liedern. Mit u.a. Magdalena Hinterdobler (Sopran), Mauro Peter (Tenor), Peter Schöne (Bass), Madrigalchor der Hochschule für Musik und Theater München und Falk Häfner (Moderation). Tobias Koch spielt auf einem Flügel von Eduard Steingraeber (Bayreuth 1852, Opus 1). Das Konzert wird für Radio und TV aufgezeichnet und zu einem späteren Zeitpunkt gesendet. 28. Januar 2013 COTTBUS 29. Januar 2013 HANNOVER NDR Landesstudio, Funkhaus 01. Februar 2013 GREIFENBERG (Oberbayern) Greifenberger Institut für Musikinstrumentenkunde, 20 Uhr Franz Schubert: "Die schöne Müllerin", mit Markus Schäfer. Hammerflügel Louis Dulcken, München 1820 aus der Sammlung der Greifenberger Werkstatt für historische Tasteninstrumente. 02. Februar 2013 BAD NAUHEIM Waldorfschule, 17 Uhr Ludwig Berger: "Die schöne Müllerin" und Franz Schubert: "Die schöne Müllerin". Mit Markus Schäfer, Tenor 04.-07. Februar 2013 WEIMAR Stadtschloss Aufnahme von Schuberts "Schöne Müllerin" mit Markus Schäfer (Tenor) für DLR Kultur. Fortepiano Johann Fritz (Wien um 1830) aus der Sammlung von Prof. Ulrich Beetz. 15. Februar 2013 Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik / Bestenliste 1/2013 für die Aufnahme von Kammermusikwerken August Klughardts (s. CDs) 22. Februar 2013 FREIBURG im Breisgau 02./03. -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert

Die Frage, wie kommt Riedlingen an zwei so hochkarätige Solisten für die doch kleinen Galeriekonzerte, muss beantwortet werden. Zentrale Stelle ist Prof. Dr. Edward Swen- son (USA), der schon wiederholt in Riedlingen war und mit seinem Vortrag „Conrad Graf und seine Kundschaft in Europa“ die Besucher begeisterte. Begleitet wurde er damals von Stefania Neonato, die sich aus der Zeit bei Malcolm Bilson an der Ithaca Universität kannten. Prof. Malcolm Bilson, der sich auf einer Europareise befindet und. in Wien und Budapest konzertiert, konnte für die Idee gewonnen werden, zusammen mit Stefania Neonato in der Geburtsstadt des Conrad Graf auf einem Original- Instrument zu konzertieren. Die beiden Künstler stellten speziell für Riedlingen und den vorhandenen Hammerflügel ein fulminantes Konzert - Programm für zwei- und vier Hände zusammen. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Bei allem Bemühen kann man zwischen Mozart und Riedlingen keine Verbindungen nachweisen. Mozart gehört zu den Pionieren der vierhändigen Klavierkomposition; die Anregung dazu erhielt er zweifellos durch das gemeinsame Musizieren mit seiner Schwester am Cembalo. Bereits als Neunjähriger schreibt Mozart Stücke für sich und seine fünf Jahre ältere Schwester und er gilt weithin als Erfinder dieser Gattung – auch wenn tatsächlich schon Komponisten vor ihm, etwa Johann Christian Bach, sich diesem Genre widmeten. Die B-Dur Sonate KV 358 zählt zu den ersten nachweisbaren echten Werken Mozarts für Klavier vierhändig. (Anja Renczikowski) Ludwig van Beethoven Gegen Ende 1825 hat Conrad Graf Beethoven leihweise einen vierchörigen Flügel zur Verfügung gestellt. Nach Beethovens Tod hat Graf sein Instrument wieder zurückgenommen und später verkauft (heute im Beethovenhaus Bonn). Vielleicht hat Beethoven für die Überlassung seines Flügels Graf insofern gedankt, als er ihm das Autograph seiner Klaviersonate in e-Moll, Op. -

Museum and Digital Beethoven-Haus a Brief Guide

BEETHOVEN’S BIRTHPLACE Beethoven-Haus Bonn museum and digital beethoven-haus a brief guide BEETHOVEN-HAUS BONN BEETHOVEN’S BIRTHPLACE museum Beethoven – oRiginal anD Digital digital beethoven- haus The Beethoven family lived for some years in the yellow house on the lefthand side in the courtyard of the set of buildings which today comprise the Beethoven Haus. Ludwig van Beethoven was born here in Decem ber 1770. Since 1889 the BeethovenHaus Society has maintained a commemorative museum in the birthplace, which today houses the world’s largest Beethoven collection. The exhibition rooms contain a selection of more than 150 original documents from the time Beethoven spent in Bonn and Vienna. The hi storical building adjoining on the right (the white rear building), in which Beethoven’s christening was once celebrated, has since 2004 accommodated the “Digital BeethovenHaus”. Modern methods of presentation lead the visitor on a journey of exploration through Beethoven’s life and work (Studio of Digital Archives). His music is interpreted in a completely new way as audiovisual art and for the first time it is presented virtually (Stage for Musical Visualisation). TOUR You may begin your tour as you wish with: • Beethoven’s Birthplace (museum), the yellow house, entered from the courtyard • the Digital archives studio (multimediabased Beethoven), the white house (ground floor), entered from the Sculptures Courtyard • the stage for Musical visualisation (virtual theatre), performance times available at the ticket office, meeting point -

INTERNATIONAL FORTEPIANO SALON #5: Pioneers: Fortepiano in China

Catskill Mountain Foundation presents INTERNATIONAL FORTEPIANO SALON #5: Pioneers: Fortepiano in China Hosted by the Academy of Fortepiano Performance in Hunter, NY SATURDAY MAY 22, 2021 @ 9 pm (Eastern Daylight Saving Time) (Sunday, May 23, 2021 @ 9 am China Time) Hosted by Yiheng Yang and Maria Rose Founders and faculty of the Academy of Fortepiano Performance in Hunter, NY Guest Hosts: Audrey Axinn (Tianjin) Yuan Sheng (Beijing) Yuehan Wang (Beijing) Also Featuring: Michael Tsalka, Zijun Wang, and Jing Tang PROGRAM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo in F major, K.494 Audrey Axinn, Anton Walter fortepiano (replica by Paul McNulty) Frédéric Chopin Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 69, No. 2 Nocturne in D-Flat Major, Op. 2 Yuan Sheng, 1836 Pleyel piano Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata in E-flat Major, K.282 Adagio, Menuetto Yuehan Wang, Anton Walter fortepiano (replica by Paul McNulty) Franz Schubert Impromptu in G-Flat Major, Op. 90, No. 3 Johann Baptist Wanhal Capriccio in E-Flat Major, Op. 15, No. 2 (1786) Michael Tsalka, 1838 Conrad Graf piano; ca. 1785 Johann Bohack fortepiano Franz Schubert Sonata in C Minor, D.958 Allegro (4th movt.) Zijun Wang, Graf fortepiano (replica by Paul McNulty) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Fantasy in D minor, K.397 Jing Tang, Anton Walter fortepiano (replica by Paul McNulty) BIOGRAPHIES A sensitive and compelling performer and educator, Audrey Axinn is currently Associate Dean and faculty at the Tianjin Juilliard School. She is also on faculty at New York Juilliard and Mannes School of Music. She has performed widely at venues such as the Boston Early Music and Edinburgh Festivals and taught master classes at almost two dozen conserva- tories in Asia, Europe and North America. -

Learn More About the Steinway N°1 Replica

Tradition, Innovation, Perfection From Instrument No. 1 to Today Inventing the Piano »A Steinway is a Steinway and there is nothing like it in the world.« In 1700, Italian Bartolomeo de Francesco Cristofori (1655-1731) made musical history when fortepianos began to be fitted with a “hammer” action. When piano builder John Broadwood Arthur Rubinstein he presented the first fortepiano to Prince Ferdinando de Medici. The pianoforte was born, became the first person to extend the keyboard from Cristofori’s original four octaves to six, the name being derived from its ability to produce different levels of sound—both “piano” another significant milestone in the piano’s development had been achieved. Two other (quiet) and “forte” (loud). By around 1726, Cristofori had refined the instrument to such an important inventions were the work of Sebastian Erard, in the shape of the patented agraffe, extent that it already contained the components still used in piano building today. Word of through which strings were threaded, and the repetition action. Today’s grand piano actions this new keyboard instrument reached Germany in the are still built according to Erard’s design. early 18th century. Gottfried Silbermann, for instance, By the early 19th century, it was clear that the fortepianos unveiled his first fortepiano in 1726, after much experi- had become firmly established. Now fashionable, it was mentation. Johann Andreas Stein was another pioneer, found in affluent private homes as well as concert halls. working tirelessly on developing a sort of “escapement” When the piano industry was experiencing this boom action, which created a sensation in 1750 and led to the in 1800, Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg was a mere three development of the Viennese action. -

Schubertiade ‘Du Holde Kunst, Ich Danke Dir’ Anima Eterna Brugge Jos Van Immerseel

SCHUBERTIADE ‘DU HOLDE KUNST, ICH DANKE DIR’ ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE JOS VAN IMMERSEEL 1 MENU › TRACKLIST › ENGLISH TEXT › TEXTE FRANÇAIS › NEDERLANDSE TEKST › DEUTSCHER TEXT › SUNG TEXTS › TEXTES CHANTÉS › GEZONGEN TEKSTEN › GESUNGENE TEXTE SCHUBERTIADE ‘DU HOLDE KUNST, ICH DANKE DIR’ ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE JOS VAN IMMERSEEL CD1 1 STÄNDCHEN (ERSTE FASSUNG) D 920 5’29 MEZZO, VOCAL QUARTET, FORTEPIANO 2 AUF DER BRUCK D 853 3’58 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 3 GRETCHEN AM SPINNRADE D 118 3’36 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO 4 DIE NACHT D 983C 2’42 VOCAL QUARTET 5 MARCHE CARACTÉRISTIQUE D 886/2 6’27 FORTEPIANO* (FOUR HANDS) 6 DIE JUNGE NONNE D 828 4’45 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO QUINTETT ‘DIE FORELLE’ D 667 VIOLIN, VIOLA, CELLO, DOUBLE BASS, FORTEPIANO* 7 ALLEGRO VIVACE 13’26 8 ANDANTE 7’12 9 SCHERZO 4’32 10 ANDANTINO (THEME & VARIATIONS) 7’47 11 ALLEGRO GIUSTO 7’12 TOTAL TIME: 67’12 CD2 1 NACHTGESANG IM WALDE D 913 6’08 VOCAL QUARTET, HORN QUARTET 2 GANYMED D 544 4’17 SOPRANO, FORTEPIANO 3 DU LIEBST MICH NICHT D 756 3’44 MEZZO, FORTEPIANO 4 ANDANTE (TRIO IN E FLAT MAJOR) D 929/2 10’01 VIOLIN, CELLO, FORTEPIANO* 5 L’INCANTO DEGLI OCCHI D 902/1 2’54 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 6 IL TRADITOR DELUSO D 902/2 3’48 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 7 IL MODO DI PRENDER MOGLIE D 902/3 4’25 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO DIVERTISSEMENT À LA HONGROISE D 818 FORTEPIANO* (FOUR HANDS) 8 ANDANTE 10’54 9 MARCIA, ANDANTE CON MOTO 3’06 10 ALLEGRETTO 13’50 TOTAL TIME: 63’13 CD3 1 FANTASIE IN F MINOR D 940 18’11 FORTEPIANO* ( FOUR HANDS) 2 DER WANDERER D 489 4’55 BARITONE, FORTEPIANO 3 NACHT UND TRAÜME D 827 3’46 SOPRANO, -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Moschos, P. (2006). Performing Classical-period music on the modern piano. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8485/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] PERFORMING CLASSICAL-PERIOD MUSIC ON THE MODERN PIANO Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) Petros Moschos ýý*** City University Music Department June 2006 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................. iii Abstract ................................................................................................ iv List figures -

Classical Vienna 1

Classical Vienna Music for Guitar & Piano James Akers romantic guitar Gary Branch fortepiano RES10182 Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841) Classical Vienna 1. Nocturne No. 1 [4:33] Music for Guitar & Piano Anton Diabelli (1781-1858) Sonata for the Piano Forte and Guitar, Op. 71 2. Allegro moderato [5:42] 3. Menuetto & Trio [4:48] James Akers romantic guitar 4. Polonaise [3:15] Ignaz Moscheles (1794-1870) Gary Branch fortepiano 5. Fantasia on ‘Potem Mitzwo!’ [6:12] Ferdinando Carulli 6. Nocturne No. 2 [3:45] Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) Sonata Brillante, Op. 15 7. Allegro [6:06] 8. Adagio [4:59] Mauro Giuliani Variations on ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ & Polonaise 9. Introduzione [1:57] 10. Variations [7:44] 11. Polonaise [9:14] About James Akers: Ferdinando Carulli ‘It’s a small soundscape, but when played with such beauty, 12. Variations on Themes taste and subtlety, an utterly enchanting one.’ by Rossini [9:24] BBC Music Magazine Total playing time [67:47] Classical Vienna: Music for Guitar resounded to more comforting sounds. Music and Fortepiano publishers poured out vast quantities of works written by skilled craftsmen composers intent By the early-nineteenth century, long term on quieting, not arousing, the latent and societal changes in Europe had created a unseemly passions of the European elite. prosperous and expanding middle class. The values and culture of this group, mainly The market for music lessons, sheet music concerned with aspiration and self- and performances provided gainful improvement, quickly became established, employment for the composers featured on and remained reasonably consistent this recording, many of whom were able to thereafter. -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2011-2012 CONCERTS FROM

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2011-2012 CONCERTS FROM The Carolyn Royall Just Fund Martin Bruns, baritone Christoph Hammer, fortepiano The Franz Liszt Bicentenary Project Saturday, October 22, 2011 Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Saturday, October 22, 2011 – 8:00 pm MARTIN BRUNS, baritone • CHRISTOPH HAMMER, piano PROGRAM Freudvoll und leidvoll, op. 84; transcribed for solo piano by Franz Liszt, S. 468 Ludwig van BEETHOVEN Freudvoll und leidvoll, op. 84 (Goethe) (1770-1827) Wonne der Wehmut, op. 83, no. 1 Neue Liebe, neues Leben, op. 75, no. 2 (Goethe) Freudvoll und leidvoll, S. 280 (Goethe) Franz LISZT O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst (Liebesträume), S. 541/3 (Freiligrath) (1811-1886) Seliger Tod, S. 541/2, transcribed for solo piano by Liszt from his own Liebesträume, S. 307 Tout n’est qu’images fugitives, WWV 58 (Reboul) Richard WAGNER Der Tannenbaum, WWV 50 (Scheuerlin) (1813-1883) Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam, S. 309 (Heine) Franz LISZT Vergiftet, sind meine Lieder, S. 289 (Heine) Oh ! Quand je dors, S. 282 (Hugo) Intermission Tre Sonetti del Petrarca, S. 270 Franz LISZT 1. Benedetto sia ‘l giorno e ‘l mese e l’anno… 2. Pace no trovo… 3. I’ vidi in terra angelici costume… Mädchens Wunsch, op. 74, transcribed for solo piano by Liszt, S. 480 Frédéric CHOPIN (1810-1849) Petrarca-Chopin: Tre Madrigali, op. 74 Mario CASTELNUOVO-TEDESCO 1. Non al suo amante più Diana piacque (1895-1968) 2. Perch’al viso d’Amor portava insegna 3. Nova angeletta sovra l’ale accorta Des Tages laute Stimmen schweigen, S. -

The First Fleet Piano: Volume

THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One GEOFFREY LANCASTER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Lancaster, Geoffrey, 1954-, author. Title: The first fleet piano : a musician’s view. Volume 1 / Geoffrey Richard Lancaster. ISBN: 9781922144645 (paperback) 9781922144652 (ebook) Subjects: Piano--Australia--History. Music, Influence of--Australia--History. Music--Social aspects--Australia. Music, Influence of. Dewey Number: 786.20994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover based on an original design by Gosia Wlodarczak. Cover design by Nic Welbourn. Layout by ANU Press. Printed by Griffin Press. This edition © 2015 ANU Press. Contents List of Plates . xv Foreword . xxvii Acknowledgments . xxix Descriptive Conventions . xxxv The Term ‘Piano’ . xxxv Note Names . xxxviii Textual Conventions . xxxviii Online References . xxxviii Introduction . 1 Discovery . 1 Investigation . 11 Chapter 1 . 17 The First Piano to be Brought to Australia . 22 The Piano in London . 23 The First Pianos in London . 23 Samuel Crisp’s Piano, Made by Father Wood . 27 Fulke Greville Purchases Samuel Crisp’s Piano . 29 Rutgerus Plenius Copies Fulke Greville’s Piano . 31 William Mason’s Piano, Made by Friedrich Neubauer(?) . 33 Georg Friedrich Händel Plays a Piano .