Clef Transposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enharmonic Substitution in Bernard Herrmann's Early Works

Enharmonic Substitution in Bernard Herrmann’s Early Works By William Wrobel In the course of my research of Bernard Herrmann scores over the years, I’ve recently come across what I assume to be an interesting notational inconsistency in Herrmann’s scores. Several months ago I began to earnestly focus on his scores prior to 1947, especially while doing research of his Citizen Kane score (1941) for my Film Score Rundowns website (http://www.filmmusic.cjb.net). Also I visited UCSB to study his Symphony (1941) and earlier scores. What I noticed is that roughly prior to 1947 Herrmann tended to consistently write enharmonic notes for certain diatonic chords, especially E substituted for Fb (F-flat) in, say, Fb major 7th (Fb/Ab/Cb/Eb) chords, and (less frequently) B substituted for Cb in, say, Ab minor (Ab/Cb/Eb) triads. Occasionally I would see instances of other note exchanges such as Gb for F# in a D maj 7 chord. This enharmonic substitution (or “equivalence” if you prefer that term) is overwhelmingly consistent in Herrmann’ notational practice in scores roughly prior to 1947, and curiously abandoned by the composer afterwards. The notational “inconsistency,” therefore, relates to the change of practice split between these two periods of Herrmann’s career, almost a form of “Before” and “After” portrayal of his notational habits. Indeed, after examination of several dozens of his scores in the “After” period, I have seen (so far in this ongoing research) only one instance of enharmonic substitution similar to what Herrmann engaged in before 1947 (see my discussion in point # 19 on Battle of Neretva). -

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele IT’S EASY WITH THE LEE OSKAR HARMONICA SYSTEM... SpiceSpice upup youryour songssongs withwith thethe soulfulsoulful soundsound ofof thethe harmonicaharmonica alongalong withwith youryour GuitarGuitar oror UkuleleUkulele playing!playing! Information all in one place! Online Video Guides Scan or visit: leeoskarquickguide.com ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. - All Rights Reserved Major Diatonic Key labeled in 1st Position (Straight Harp) Available in 14 keys: Low F, G, Ab, A, Bb, B, C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#, High G Key of C MAJOR DIATONIC BLOW DRAW The Major Diatonic harmonica uses a standard Blues tuning and can be played in the 1st Position (Folk & Country) or the 2 nd Position (Blues, Rock/Pop Country). 1 st Position: Folk & Country Most Folk and Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the blow (exhale) chord. This is called 1 st Position, or straight harp, playing. Begin by strumming your guitar / ukulele: C F G7 C F G7 With your C Major Diatonic harmonica Key of C MIDRANGE in its holder, starting from blow (exhale), BLOW try to pick out a melody in the midrange of the harmonica. DRAW Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do C Major scale played in 1st Position C D E F G A B C on a C Major Diatonic harmonica. 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. All Rights Reserved 2nd Position: Blues, Rock/Pop, Country Most Blues, Rock, and modern Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the draw (inhale) chord. -

Finale Transposition Chart, by Makemusic User Forum Member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans

Finale Transposition Chart, by MakeMusic user forum member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans. Sounding Written Inter- Key Usage (Some Common Western Instruments) val Alter C Up 2 octaves Down 2 octaves -14 0 Glockenspiel D¯ Up min. 9th Down min. 9th -8 5 D¯ Piccolo C* Up octave Down octave -7 0 Piccolo, Celesta, Xylophone, Handbells B¯ Up min. 7th Down min. 7th -6 2 B¯ Piccolo Trumpet, Soprillo Sax A Up maj. 6th Down maj. 6th -5 -3 A Piccolo Trumpet A¯ Up min. 6th Down min. 6th -5 4 A¯ Clarinet F Up perf. 4th Down perf. 4th -3 1 F Trumpet E Up maj. 3rd Down maj. 3rd -2 -4 E Trumpet E¯* Up min. 3rd Down min. 3rd -2 3 E¯ Clarinet, E¯ Flute, E¯ Trumpet, Soprano Cornet, Sopranino Sax D Up maj. 2nd Down maj. 2nd -1 -2 D Clarinet, D Trumpet D¯ Up min. 2nd Down min. 2nd -1 5 D¯ Flute C Unison Unison 0 0 Concert pitch, Horn in C alto B Down min. 2nd Up min. 2nd 1 -5 Horn in B (natural) alto, B Trumpet B¯* Down maj. 2nd Up maj. 2nd 1 2 B¯ Clarinet, B¯ Trumpet, Soprano Sax, Horn in B¯ alto, Flugelhorn A* Down min. 3rd Up min. 3rd 2 -3 A Clarinet, Horn in A, Oboe d’Amore A¯ Down maj. 3rd Up maj. 3rd 2 4 Horn in A¯ G* Down perf. 4th Up perf. 4th 3 -1 Horn in G, Alto Flute G¯ Down aug. 4th Up aug. 4th 3 6 Horn in G¯ F# Down dim. -

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

Transposition Tutorial 1

Transposition Tutorial 1 Open the transposition menu by clicking the radio button Defaults menus: 1st dropdown menu: To the following key; 2nd dropdown menu: C Major / A minor; Up and All Staves. Transposing by key: From the 2nd dropdown menu showing C Major/A minor, select a key and then choose Up or Down depending on the key. Up or Down indicates direction of the transposition. For best results, when transposing by key choose the direction which results in the smallest interval of change. Click OK to complete the transposition. To return to the original key, click Reload. Transpositions cannot be saved. Closing the selection or the viewer will automatically reset to the original key. Transposing for an instrument: From the 1st dropdown menu select: For a transposing instrument. From the 2nd dropdown menu, now showing Soprano Saxophone select your instrument. If your music is a Piano Vocal sheet, you may want to transpose only the melody by selecting Staff Number(s)1 through 1. You will transpose only the melody for the instrument you choose and the piano will remain in its correct key. Transposition Tutorial 2 Transposing for an Instrument (continued): Once you have transposed the melody line for a specific instrument you may choose to change the octave of just the melody line. For example, Tenor Saxophone transposes up an octave and a 2nd, and the resulting transposition may be too high for the instrument. From the 1st dropdown menu, select By Interval. From the 2nd dropdown menu now showing Minor Second, select Perfect Octave. Select the Down button and to transpose only the melody line select Staff Number(s) (Staff number 1 though 1 is the melody line). -

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

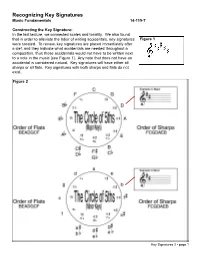

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

Written Vs. Sounding Pitch

Written Vs. Sounding Pitch Donald Byrd School of Music, Indiana University January 2004; revised January 2005 Thanks to Alan Belkin, Myron Bloom, Tim Crawford, Michael Good, Caitlin Hunter, Eric Isaacson, Dave Meredith, Susan Moses, Paul Nadler, and Janet Scott for information and for comments on this document. "*" indicates scores I haven't seen personally. It is generally believed that converting written pitch to sounding pitch in conventional music notation is always a straightforward process. This is not true. In fact, it's sometimes barely possible to convert written pitch to sounding pitch with real confidence, at least for anyone but an expert who has examined the music closely. There are many reasons for this; a list follows. Note that the first seven or eight items are specific to various instruments, while the others are more generic. Note also that most of these items affect only the octave, so errors are easily overlooked and, as a practical matter, not that serious, though octave errors can result in mistakes in identifying the outer voices. The exceptions are timpani notation and accidental carrying, which can produce semitone errors; natural harmonics notated at fingered pitch, which can produce errors of a few large intervals; baritone horn and euphonium clef dependencies, which can produce errors of a major 9th; and scordatura and C scores, which can lead to errors of almost any amount. Obviously these are quite serious, even disasterous. It is also generally considered that the difference between written and sounding pitch is simply a matter of transposition. Several of these cases make it obvious that that view is correct only if the "transposition" can vary from note to note, and if it can be one or more octaves, or a smaller interval plus one or more octaves. -

Tuning Forks As Time Travel Machines: Pitch Standardisation and Historicism for ”Sonic Things”: Special Issue of Sound Studies Fanny Gribenski

Tuning forks as time travel machines: Pitch standardisation and historicism For ”Sonic Things”: Special issue of Sound Studies Fanny Gribenski To cite this version: Fanny Gribenski. Tuning forks as time travel machines: Pitch standardisation and historicism For ”Sonic Things”: Special issue of Sound Studies. Sound Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Taylor & Francis Online, 2020. hal-03005009 HAL Id: hal-03005009 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03005009 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Tuning forks as time travel machines: Pitch standardisation and historicism Fanny Gribenski CNRS / IRCAM, Paris For “Sonic Things”: Special issue of Sound Studies Biographical note: Fanny Gribenski is a Research Scholar at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and IRCAM, in Paris. She studied musicology and history at the École Normale Supérieure of Lyon, the Paris Conservatory, and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales. She obtained her PhD in 2015 with a dissertation on the history of concert life in nineteenth-century French churches, which served as the basis for her first book, L’Église comme lieu de concert. Pratiques musicales et usages de l’espace (1830– 1905) (Arles: Actes Sud / Palazzetto Bru Zane, 2019). -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale.