Legislative Background Brief for the Economic Affairs Interim Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rbgh-Free” Momentum Building in U.S

“rbGH-Free” Momentum Building in U.S. Creamery Assn. of Oregon declared that its prized cheeses would no longer contain milk from Posilac- injected cows. Tillamook’s leadership saw sales of the co-op’s pre-eminent branded cheeses impacted by consumer concerns about rbGH. After the Tillamook co-op board of directors announced a “rbGH-Free” policy for its cheeses, then Posilac’s manufacturer—Monsanto—tried to disrupt the co- op’s membership. * In the summer 2006, Alpenrose Dairy (Redmond, Oregon) became completely “rbGH- More and more U.S. dairy processors are responding to consumer Free”. concerns by selling “rbGH-Free” dairy products. This trend was * In December 2005, Darigold’s Seattle, building fast, even before recent reports that rbGH–related hormones Washington's fluid milk supply went “rbGH-Free”. in milk were causing increased multiple human births. Darigold (formerly operating as West Farm) is mov- ing step-by-step, according to Rick North. In by Pete Hardin Nutrition, where author Dr. Gary Steinman reports February 2006, Darigold shifted production of its that a secondary hormone related to “Posilac” injec- Increased consumer demand for “rbGH-Free” yogurt to a “rbGH-Free” plant. tions—Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), may dairy products is driving more dairy processors to be causing up to a five-fold increase in births of require their raw milk supplies contain no milk from twins in milk-drinking women in the U.S. Global hospital wellness group: anti-rbGH dairy farms using Monsanto’s synthetic, milk-stim- ulating cow growth hormone—“Posilac”. Rick North reports another key organization is Meatrix 2 video targets factory dairies/rbGH involved with the “anti-rbGH” effort is an interna- Some raw milk marketers are absorbing higher tional group—Health Care Without Harm. -

Our Donors Page 1 of 20 CORPORATIONS, FOUNDATIONS, ORGANIZATIONS, and INDIVIDUALS

Our Donors page 1 of 20 CORPORATIONS, FOUNDATIONS, ORGANIZATIONS, AND INDIVIDUALS Our Donors Thank you to everyone who made an investment in girls in 2019 by supporting Girl Scouts of Western Washington. The gifts below were made between October 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019. Donors are listed alphabetically. CORPORATIONS, FOUNDATIONS, ORGANIZATIONS, AND INDIVIDUALS AbbVie Employee Alaska Airlines Mr. & Mrs. Dale Anderson Nora Arendt Engagement Fund Denise Alessi Ann Anderson Mark Armstrong Jessica Abella Sara Alexander Amy Anderson Ellen Aronson Kendra Abernethy Emily Alford Kristen Anderson Raaji Asaithambi David Abrams Sally Alfred Sharon Anderson Masashi Asao Shannon Abrams Mark Allan Ms. Mary Anderson Kristine Ashcraft Divya Abrol Claudia Allard Karrie Anderson Bredstrand Virginelle Ashe Accenture LLP Jenni Allen Ms. Adrienne Anderson- Kelly Ashley Smith Barbara Acevedo Visser Brittany Allen Erin Ashley Kerry Lee Andken Vicki Adams Adrienne Allen AT&T Employee Giving Ms. Jennifer Andress Campaign Rachel Adams Jay Allen Evelyn Andrews Charity Atchison Carol Adams Lisa Allenbaugh Chantey Andrews Martin Atkinson Kristina Adams Sally Allwardt Duff & Marilyn Andrews Jill Aul Kateryna Adams Pamela Almaguer-Bay Virginia Andrews Burdette Michelle Auster Susan Adams-Provost Nicole Aloni Courtney Angeles Kerry Axley Ereisha Addo Lara Alpert Urban Animal AYCO Charitable Foundation Penny Jo Adler Sharia Al-Rashid Mary Ann Ruth Bacha Lea Aemisegger Lea Rachelle Alston Anonymous Hannah Bachelder Martha E. Ahart Amazon Smile Anonymous Jennifer Bachhuber Saher Ahmad Hanan Amer Melissa Aparico Lisa Baer Samantha Aiello American Legion George Morris Post No 129 Janet Aradine Mona Baghdadi Sheryle Aijala Ameriprise Financial Jennifer Aragon Morges Bahru Levy Aitken Brooke Andersen Ann Ardizzone Julia Bai William Aitken Elspeth Baron Anderson Judge Stephanie Arend Brittany Bailey Julie Kane Akhter We hope your gift is acknowledged accurately. -

Outdoor-Industry Jobs a Ground Level Look at Opportunities in the Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Outdoor Recreation Sectors

Outdoor-Industry Jobs A Ground Level Look at Opportunities in the Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Outdoor Recreation Sectors Written by: Dave Wallace, Research Director, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Chris Dula, Research Investigator, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Randy Smith, IT and Research Specialist, Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board Alan Hardcastle, Senior Research Manager, WSU Energy Program, Washington State University James Richard McCall, Research Assistant, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC), Washington State University Thom Allen, Project Manager, Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC), Washington State University Executive Summary Washington’s Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board (Workforce Board) was tasked by the Legislature to conduct a comprehensive study1 centered on outdoor and field-based employment2 in Washington, which includes a wide range of jobs in the environment, agriculture, natural resources, and outdoor recreation sectors. Certainly, outdoor jobs abound in Washington, with our state’s Understating often has inspiring mountains and beaches, fertile and productive farmland, the effect of undervaluing abundant natural resources, and highly valued natural environment. these jobs and skills, But the existing data does not provide a full picture of the demand for which can mean missed these jobs, nor the skills required to fill them. opportunities for Washington’s workers Digging deeper into existing data and surveying employers in these and employers. sectors could help pinpoint opportunities for Washington’s young people to enter these sectors and find fulfilling careers. This study was intended to assess current—and projected—employment levels across these sectors with a particular focus on science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) oriented occupations that require “mid-level” education and skills. -

STANDING COMMITTEE MINUTES City of Spokane Urban Development Committee 11/13/2017 - FINAL

STANDING COMMITTEE MINUTES City of Spokane Urban Development Committee 11/13/2017 - FINAL Attendance Council President Ben Stuckart, Council Member Mumm, Council Member Karen Stratton, Council Member Laurie Kinnear, Council Member Amber Waldref, Council Member Mike Fagan, Council Member Breean Beggs, Gavin Cooley, Jonathan Mallahan, Andrew Worlock, Hannalee Allers, Nathen Calene, Anna Everano, Jacob Fraley, Jacqui Halvorson, Brian McClatchey, Adam McDaniel, Skyler Oberst, Teri Stripes, Ali Brast, Eldon Brown, Laura Williams Non-City Employees: Karl Otterstrom - STA Approval of Minutes: The approval of the meeting minutes for October was deferred until the December Urban Development Committee Meeting. Agenda Items: 1. Strategic Investments – Council President Stuckart Council President Stuckart briefed the Committee regarding this item. Please see attached briefing paper. 2. Skywalk Permitting Ordinance – Council President Stuckart Council President Stuckart briefed the Committee regarding this item. Please see attached briefing paper and ordinance. 3. Resolution Opposing the House of Representatives Tax Cuts & Jobs “Tax Reform” Bill – Council President Stuckart Council President Stuckart briefed the Committee regarding this item. Please see attached briefing paper and resolution. 4. Briefing on the Monroe Street Business Support Plan – Council Member Mumm Council Member Mumm briefed the Committee regarding this item. 5. Residential Parking Enforcement: discussion – Council Member Stratton Council Member Stratton briefed the Committee regarding this item. This was a discussion item only pertaining to certain regulations regarding parking vehicles on streets and the rules that apply. 6. A Rezone from Residential Single Family to Residential Single Family Compact for the Ivory Abbey near the Perry District – Ali Brast Ali Brast, Development Services Center, Briefed the Committee regarding this item. -

Member-Investment-Le

WCIT MEMBERSHIP Insights, Advocacy, Actions BECOME A WCIT Member TODAY Become a WCIT member today and join a diverse group of small and medium-sized companies, Fortune 500 businesses and agriculture producers that together advocate for the competitiveness of Washington state’s trade economy. When you join WCIT, you get: A distinguished and highly-involved network of business leaders, community leaders, elected officials and diplomats invested in advancing goals of mutual interest Access to exclusive meetings and briefings on relevant trade issues and behind-the-scenes updates on current issues impacting trade-related businesses In-depth engagement with leading authorities on issues such as the trade war, NAFTA renegotiation, trade enforcement and more Bi-weekly updates on trade policy and discounts on event registrations In addition, WCIT is a sought-after voice on trade and competitiveness issues, and we use the strength of our platforms to highlight our members: Video Storytelling amplifies company member messaging with the media and other influencers, advancing your agenda and promoting the people behind the scenes. Social Media Marketing elevates our member companies’ priorities and brands to advance their reputations and trade goals alike. With followers like the United States Trade Representative, key congressional leaders, the International Trade Administration and more, WCIT’s influence in this increasingly important aspect of policy advocacy can move the needle on priority issues. News Media regularly seeks out WCIT for insights to be quoted in the press, make appearances on local and national broadcasts, author trade op-eds, and meet with editorial boards. We frequently refer reporters to member companies interested in getting their trade stories out. -

Matching Gift Programs

Plexus Technology Group,$50 SPX Corp,d,$100 TPG Capital,$100 U.S. Venture,$25 Maximize the Impact of Your Gift Plum Creek Timber Co Inc.,$25 SPX FLOW,d,$100 TSI Solutions,$25 U.S.A. Motor Lines,$1 Pohlad Family Fdn,$25 SSL Space Systems/Loral,$100 Tableau Software,$25 UBM Point72 Asset Mgt, L.P. STARR Companies,$100 Taconic Fdn, Inc.,$25 UBS Investment Bank/Global Asset Mgt,$50 Polk Brothers Fdn Sabre Holdings Campaign (October 2017),$1 Taft Communications,$1 Umpqua Bank,$1 Polycom Inc.,$20 Safety INS Group, Inc.,$250 Takeda Pharma NA,$25 Unilever North America (HQ),s,d Portfolio Recovery Associates,$25 Sage Publications, Inc.,$25 Talent Music,$5 Union Pacific Corp MoneyPLUS,d Match Your Gift PotashCorp,d,$25 Salesforce.com,$50 Tallan Union Pacific Corp TimePLUS,$25 Potenza,$50 Sallie Mae Dollars for Doers,d Talyst,$25 United States Cellular Corp,$25 when you donate to Power Integrations,$25 Saltchuk,$25 Tampa Bay Times Fund,r,$25 United Technologies Corp - UTC,d,$25 Praxair,d,$25 Samaxx,$5 TargetCW,$1 UnitedHealth Group Precor,$25 Samuel Roberts Noble Fdn Inc.,d,$100 Teagle Fdn, Inc.,d UnitedHealth Group (Volunteer) Preferred Personnel Solutions SanMar Technology Sciences Group,$10 Universal Leaf Tobacco Corp,$25 Preformed Line Products Co,r,d,$25 Sandmeyer Steel Co,r,$50 Teichert, Inc. Unum Corp,2:1,d,$50 Premier, Inc.,$50 Sanofi,$50 Teknicks,$1 Premier, Inc. Volunteer,$25 Schneider Electric Co (Cash & Volunteer),d,$25 Tektronix, Inc.,d,$20 Principal Financial Group,r,$50 Scripps Networks Interactive,r,$25 Teleflex,r,d,$50 V/W/X/Y/Z VISA Intl ProLogis,d,$50 Scripps Networks Volunteer,d,$250 Teradata Campaign (October),$25 VMware Inc.,$31 ProQuest LLC,$25 Securian Financial Group,r,d,$35 Terex Corp,$50 Vanderbilt Ventures, Inc. -

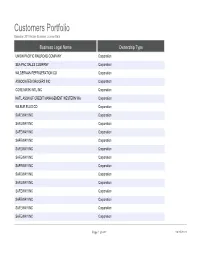

Customers Portfolio Based on 2010 Active Business License Data

Customers Portfolio Based on 2010 Active Business License Data Business Legal Name Ownership Type UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY Corporation SEA PAC SALES COMPANY Corporation WILDERMAN REFRIGERATION CO Corporation ASSOCIATED GROCERS INC Corporation CORE MARK INTL INC Corporation NATL ASSN OF CREDIT MANAGEMENT WESTERN WA Corporation WILBUR ELLIS CO Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation SAFEWAY INC Corporation Page 1 of 482 09/25/2021 Customers Portfolio Based on 2010 Active Business License Data Trade Name City, State, Zip UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY SEATTLE, WA 98108 SEA-PAC SALES COMPANY KENT, WA 98032 WILDERMAN REFRIGERATION CO SEATTLE, WA 98109 ASSOCIATED GROCERS INC SEATTLE, WA 98118 CORE-MARK INTL INC LAKEWOOD, WA 98499 NACM WESTERN WASHINGTON & ALASKA SEATTLE, WA 98121 WILBUR-ELLIS CO AUBURN, WA 98001 SAFEWAY INC BELLEVUE, WA 98005 SAFEWAY INC #1477 SEATTLE, WA 98107 SAFEWAY STORE #1062 SEATTLE, WA 98116 SAFEWAY STORE #1143 SEATTLE, WA 98117 SAFEWAY STORE #1508 SEATTLE, WA 98118 SAFEWAY STORE #1550 SEATTLE, WA 98115 SAFEWAY STORE #1551 SEATTLE, WA 98112 SAFEWAY STORE #1586 SEATTLE, WA 98125 SAFEWAY STORE #1845 SEATTLE, WA 98103 SAFEWAY STORE #1885 SEATTLE, WA 98119 SAFEWAY STORE #1965 SEATTLE, WA 98118 SAFEWAY STORE #1993 SEATTLE, WA 98112 SAFEWAY STORE #219 SEATTLE, WA -

People Helping Pets… Pet Helping People

People Helping Pets… Pet Helping People Below is a list of companies that may offer employee matching gift programs. Please check with your HR department to find out if your company offers this benefit. Adobe Systems Incorporated Liberty Mutual Alaska Airlines Macy's, Inc. American Express Company MasterCard Worldwide, Inc. American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Mattel, Inc. Amgen Inc. Maytag Corporation AON Corporation/AON Inc. McDonald's Corporation Assurant Employee Benefits Merck & Co., Inc. AT&T, Inc. Microsoft Corporation AT&T Mobility, LLC Mitsubishi International Corporation Bank of America Corporation Morgan Stanley Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Motorola The Boeing Company Nintendo of America, Inc. BP America, Inc. Northern Trust Company Caterpillar Inc. Oracle Chevron Corporation PepsiCo Foundation Cigna Corporation Pfizer Inc. Cisco Systems, Inc. Philip Morris International Inc. CITGO Petroleum Company Pitney Bowes Inc. Citigroup Inc. Polaroid Corporation/Primary PDC The Coca Cola Company Prudential Financial, Inc. Corning Incorporated RBC Dain Rauscher Corp. Costco Wholesale RealNetworks Inc. Darigold, Inc. Russell Investments Deloitte Safeco Corporation Eli Lilly and Company Sara Lee Corporation Exxon Mobil Corporation Shaklee Corporation Fannie Mae Sony Corporation of America Gap Inc. Spiegel, Inc. GE Foundation Starbucks General Mills Inc. Subaru of America, Inc. The Gillette Company Texas Instruments Incorporated GlaxoSmithKline Foundation Time Warner Inc. Goodrich Corporation The Toro Company Hasbro, Inc. Union Pacific Corporation H.J. Heinz Company United Parcel Service, Inc. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company U.S. Bancorp HP Compaq The Vanguard Group, Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation Verizon Communications Inc. J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. Vulcan Materials Company John Hancock Funds, LLC Washington Dental Service Kellogg Company Wells Fargo & Company Keycorp, Key Bank Foundation The West Group, Inc. -

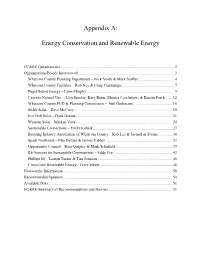

Appendix A: Energy Conservation and Renewable Energy

Appendix A: Energy Conservation and Renewable Energy EC&RE Questionnaire .................................................................................................................... 2 Organizations/People Interviewed .................................................................................................. 3 Whatcom County Planning Department – Nick Smith & Mark Sniffen .................................... 4 Whatcom County Facilities – Rob Ney & Craig Cummings ...................................................... 7 Puget Sound Energy – Lynn Murphy ......................................................................................... 9 Cascade Natural Gas – Alyn Spector, Kary Burin, Monica Cowlishaw, & Kristin Forck ....... 12 Whatcom County PUD & Planning Commission – Atul Deshmane ........................................ 16 Silfab Solar – Dave McCarty .................................................................................................... 19 EcoTech Solar – Dana Brandt ................................................................................................... 21 Western Solar – Markus Virta .................................................................................................. 24 Sustainable Connections – Emily Kubiak................................................................................. 27 Building Industry Association of Whatcom County – Rob Lee & Jacquelyn Styrna .............. 30 Spark Northwest – Mia Devine & Jaimes Valdez ................................................................... -

Sally Templeton

UNIVERSITY CONSULTING ALLIANCE Sally Templeton PHILOSOPHY STATEMENT Understanding oneself deeply is essential to being an extraordinary leader. Knowing that one’s experiences, philosophies and values can drive one’s behavior, and understanding how they drive it, awaken a leader to their own strengths, opportunities and potential pitfalls. Knowing yourself as well as one can – taking off blinders, realizing one’s impact and how one is reflected in others’ eyes – allows a leader to realistically assess how to leverage their strengths, and adjust for their weaknesses. With customized, confidential coaching, an individual not only gains this information about oneself, but learns how to use this information in combination with the culture and expectations of their organization and community. Add the learning of proven tools and processes for change, communication and management, and they can transform themselves into an extraordinarily effective leader: a leader who delivers the desired results while increasing trust and respect, developing staff members, and contributing to a stellar team. AREAS OF EXPERTISE/RESULTS Leadership Coaching Team Development Management Skills Behavior Styles Applications Communications Skills Career Coaching Leading Organizational Change EXPERIENCE / SELECTED PROJECTS Provided leadership coaching to executives from the University of Washington, Microsoft, Landis & Gyr, Silver Reef Casino, Wizards of the Coast, and others CONSULTANT PROFILE Developed and delivered mentor training to the NCAA Delivered -

FRANKLIN D. CORDELL PRACTICE AREAS Insurance Recovery And

1001 Fourth Avenue, Suite 4000 Seattle, Washington 98154 T 206.467.6477 F 206.467.6292 D 206.805.6610 Franklin D. Cordell [email protected] www.gordontilden.com FRANKLIN D. CORDELL PRACTICE AREAS Insurance Recovery and Commercial Litigation PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Partner, Gordon Tilden Thomas & Cordell LLP, 2007 – Present Partner, Gordon Murray Tilden, LLP, 1998 – 2007 Associate, Gordon Murray Tilden, LLP, 1996 – 1998 Associate (Insurance and Litigation Practice Groups), Covington & Burling, Washington, D.C., 1992 – 1996 Law Clerk to the Honorable H. Emory Widener, Jr., of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1991 – 1992 PROFESSIONAL RECOGNITION “AV” rating by Martindale-Hubbell Thompson-West Super Lawyer, Insurance Law, 2001 – Present Top-100 Vote Recipient, Washington Super Lawyer Survey, 2009 – Present Named as a “Rising Star” by Washington Law & Politics Magazine, 1999 and 2001 Listed in The Best Lawyers in America, Insurance Law EDUCATION Washington & Lee University School of Law , J.D. summa cum laude, 1991 Senior Lead Articles Editor, Washington & Lee Law Review, 1990 – 1991 Order of the Coif, 1991 American Jurisprudence Awards, Nine Courses, 1989 – 1991 University of Virginia , B.A., 1988 REPRESENTATIVE MATTERS ■ Represented The Boeing Company as lead coverage counsel since late 1990s. Participated in recoveries of insurance proceeds in the hundreds of millions of dollars, under wide range of coverage lines. ■ Represented Weyerhaeuser Company in multiple insurance claims and high-stakes coverage litigation, 1990s through the present. ■ Appointed by the State of Washington as Special Assistant Attorney General, responsible for all insurance-coverage advice and litigation on behalf of the State, 2000 through 2013. -

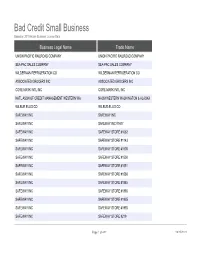

Bad Credit Small Business Based on 2010 Active Business License Data

Bad Credit Small Business Based on 2010 Active Business License Data Business Legal Name Trade Name UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY SEA PAC SALES COMPANY SEA-PAC SALES COMPANY WILDERMAN REFRIGERATION CO WILDERMAN REFRIGERATION CO ASSOCIATED GROCERS INC ASSOCIATED GROCERS INC CORE MARK INTL INC CORE-MARK INTL INC NATL ASSN OF CREDIT MANAGEMENT WESTERN WA NACM WESTERN WASHINGTON & ALASKA WILBUR ELLIS CO WILBUR-ELLIS CO SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY INC #1477 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1062 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1143 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1508 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1550 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1551 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1586 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1845 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1885 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1965 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #1993 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #219 Page 1 of 482 09/25/2021 Bad Credit Small Business Based on 2010 Active Business License Data City, State, Zip SEATTLE, WA 98108 KENT, WA 98032 SEATTLE, WA 98109 SEATTLE, WA 98118 LAKEWOOD, WA 98499 SEATTLE, WA 98121 AUBURN, WA 98001 BELLEVUE, WA 98005 SEATTLE, WA 98107 SEATTLE, WA 98116 SEATTLE, WA 98117 SEATTLE, WA 98118 SEATTLE, WA 98115 SEATTLE, WA 98112 SEATTLE, WA 98125 SEATTLE, WA 98103 SEATTLE, WA 98119 SEATTLE, WA 98118 SEATTLE, WA 98112 SEATTLE, WA 98118 Page 2 of 482 09/25/2021 Bad Credit Small Business Based on 2010 Active Business License Data SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #3091 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #368 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #373 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY STORE #423 SAFEWAY INC SAFEWAY