Scripture in the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin Dei Verbum 2013, N

digital BDV English Edition 2013, n. 1-4 digital BDV Bulletin Dei Verbum English Edition 2013, n. 1-4 Contents Editorial Thomas P. Osborne “… The ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat” (Gen 8:4) 2 Forum Father Mark Sheridan, osb The Bible as read by the Fathers of the Church 3 Prof. Dr. Thomas Söding Exegesis as Theology, Doing Theology as Exegesis: A Difficult but Necessary Alliance 15 Prof. Dr. Florian Wilk Hermeneutics of the Bible from a Protestant Perspective 23 Projects and Experiences Sr. Anna Damas SSpS Experiences with Bibliodrama in Papua-New Guinea 34 Federation News CBF Message to the Holy Father on the Occasion of His Election to the Papacy 36 Pope Francis’ Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, N. 174-175 37 Message of the Executive Committee of the Catholic Biblical Federation 38 The CBF welcomes a new associate member from Peru! 48 New Subregional Coordinators for Central Europe and Southern and Western Europe 48 Father Jan Jacek Stefanów, SVD appointed new CBF General Secretary 49 Biblical Pastoral Publications 50 BDV digital is an electronic publication of the Catholic Biblical Federation, General Secretariat, D-86941 Sankt Ottilien, [email protected], www.c-b-f.org. Editorial Board: Thomas P. Osborne and Gérard Billon Liga Bank BIC GENODEF1M05 IBAN DE28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 -- 1 -- digital BDV English Edition 2013, n. 1-4 Editorial can congress in Peru in August, the BICAM trien- nial plenary assembly in Malawi in September, the subregional meetings in Warsaw in Septem- ber and in Maynooth near Dublin, with the active “… The ark came to rest on the moun- presence of a delegate of the General Secretariat, tains of Ararat” (Gen 8:4) witness to the renewed spirit of communication and solidarity within the Federation. -

Word of God, Baptism, Eucharist in the Mission of the Church

WORD OF GOD, BAPTISM, EUCHARIST IN THE MISSION OF THE CHURCH “In calling upon all the faithful to proclaim God’s word, the Synod Fa- thers [of the 2008 General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops] restated the need in our day too for a decisive commitment to the missio ad gentes. In no way can the Church restrict her pastoral work to the ‘ordinary maintenance’ of those who already know the Gospel of Christ. Missionary outreach is a clear sign of the maturity of an ecclesial community. The Fathers also insisted that the word of God is the saving truth which men and women in every age need to hear. For this reason, it must be explicitly proclaimed. The Church must go out to meet each person in the strength of the Spirit (cf. 1 Cor 2:5) and continue her prophetic defense of people’s right and freedom to hear the word of God, while constantly seeking out the most effective ways of proclaiming that word, even at the risk of persecution. The Church feels duty-bound to proclaim to every man and woman the word that saves (cf. Rom 1:14)” (Pope Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini, 95). In the Old Testament, the Word prepares the way for the event of the Word becoming flesh. The New Testament’s Letter to the Hebrews be- gins precisely underlining this extreme dynamism of the Word: “In times past, God spoke in partial and various ways to our ancestors through the prophets; in these last days, he spoke to us through a son, whom he made heir of all things and through whom he created the universe” (Heb 1: 1-2). -

How Do the Writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "Transformation" Apply to a Couple's Growth in Holiness in Sacramental Marriage?

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? Houda Jilwan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jilwan, H. (2018). How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/194 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DO THE WRITINGS OF POPE BENEDICT XVI ON “TRANSFORMATION” APPLY TO A COUPLE’S GROWTH IN HOLINESS IN SACRAMENTAL MARRIAGE? Houda Jilwan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Philosophy and Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia 2018 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1: The universal call to holiness .................................................................................. 11 1.1 Meaning of holiness ..................................................................................................... 11 1.2 A quick overview of the universal call to holiness in Scripture and Tradition .................. -

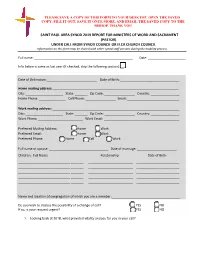

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

See Entire C.V

1 William M. Wright IV, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Professor of Theology Duquesne University 600 Forbes Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15282 412.396.5473 [email protected] Education Ph.D. (2005), Religion (New Testament). Emory University. Atlanta, GA. Dissertation: “Rhetoric and Theology: Figural Reading of John 9” o Advisor: Gail R. O’Day o Committee: Lewis Ayres, Luke Timothy Johnson, Philip Lyndon Reynolds, Vernon Robbins Minor Area: Philosophy M.T.S. (2001), Theology. University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame, IN. Concentration in biblical studies B.A. (1999), History. Baldwin-Wallace College. Berea, OH. Graduated summa cum laude Employment History and Teaching Experience 2005–present Duquesne University. Pittsburgh, PA. February 2018 Promoted to Full Professor Summer 2014 Duquesne University Italian Campus. Rome, Italy. February 2011 Granted tenure and promoted to Associate Professor August 2005 Mandatum conferred Spring 2012; Fall 2015 Adjunct professor. Saint Vincent Seminary. Latrobe, PA. June 2005 Adjunct lecturer. Spring Hill College. Mobile, AL; Atlanta, GA Adjunct lecturer for Atlanta Institute of Christian Spirituality Professional Memberships Studiorum Novi Testamenti Societas Society of Biblical Literature Catholic Biblical Association of America Eastern Great Lakes Biblical Society Academy of Catholic Theology Phi Kappa Phi Honor Society June 2019 2 TEACHING Courses Taught Duquesne University Undergraduate: UCOR 141: Biblical and Historical Perspectives IHP 145: Honors Theology o Apocalypticism and the Bible o The Mystery -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

The Synod for the Amazon

THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON Marcelo Barros • The divine revelation that arrives late1 • ABSTRACT It is good news that the Synod of Catholic Bishops from around the world, convened by Pope Francis and which will take place in October in Rome, has been prepared with extensive consultation with Amazonian communities and civil organizations working with them. The novelty of this Synod is the call for the Church, instead of acting as a teacher, to listen and hear the voice of the Amazon. In doing so, the Church will discover how to confront the challenges and new possibilities for its mission; a new vision and in opposition to the colonization in which it was complicit. KEYWORDS Spiritual listening | Catholic Church | Earth cry | Amazon peoples | Walk together • SUR 29 - v.16 n.29 • 133 - 138 | 2019 133 THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON There is no doubt that for the peoples of the Amazon, the news that Pope Francis convoked a Synod of Roman-Catholic Bishops from around the world to reflect about the appeals that the Amazon is making to the Universal Church (the body of Christian churches worldwide) was well-received. As Dom Roque Paloschi, president of the Indigenist Missionary Council in Brazil (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), affirmed, “the Synod for the Amazon practically began in January of 2018, in Puerto Maldonado (Peru), during the Pope’s meeting with Amazonian people.”2 The Synod of Bishops is an institution that continues an old church custom and enacts the Church’s vocation as a sign and instrument of unity for all of humanity. -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit. -

“Wheat from the Chaff” — Establishing the Canon

Wheat from the Chaff Establishing the Canon Donald E. Knebel May 21, 2017 Slide 1 1. This is the last presentation in this series looking at the human authors and contexts of the books that make up the Protestant Bible. 2. Today, we will look at how the books in the Bible were selected. 3. In the process, we will look at some other writings that were not selected. 4. We will then consider what it means that the Bible is the word of God. Slide 2 1. The Jewish Bible, on which the Protestant Old Testament is based, includes 24 individual books, organized into three sections – the Torah, meaning Teachings; the Nevi’im, meaning Prophets, and the Ketuvim, meaning Writings. 2. The Jewish Bible is called the Tanakh based on the first letter of the three sections. 3. Scholars remain uncertain about exactly when and how those 24 books were selected, with most believing the final selection did not take place until about 100 A.D. 4. By that time, most of the books comprising the New Testament had been written and Christianity had begun to separate from Judaism. Slide 3 1. At the time most of the books of the Protestant Old Testament were being written, the Jewish people did not have a conception of a single book that would encompass all their most important writings. 2. Instead, they had writings from various periods, some considered more reliable than others and all considered subject to revision and replacement. 3. In about 400 A.D., the prophet Nehemiah reported that Ezra had read to the people “the book of the law of Moses,” but says nothing about any other books being important at the time. -

“Know What You Believe” Answering the Tough Questions of the Christian Faith

“Know What You Believe” Answering the Tough Questions of the Christian Faith Question #7: “HOW DID WE GET THE BIBLE?” The Bible is the source and foundation of all we believe as Christians. Can we trust what it says? How do we know that the 66 books in the Bible are inspired by God? Who decided what books would be in the Bible? Tonight we will discover the fascinating story about how we got the Bible. STEP 1: REVELATION – God made known to us what otherwise would remain unknown. ➢ General Revelation – Creation (Romans 1:19-20). ➢ Special Revelation – The Living Word (Jesus Christ) and the Written Word (the Bible). STEP 2: INSPIRATION – God superintended human authors, so that by using their own individuality, they composed and recorded without error the original manuscripts. ➢ 2 Peter 1:21 “For prophecy never had its origin in the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.” ➢ 2 Timothy 3:16 “All scripture is God-breathed...” The Bible is unique in its formation: The Bible was written over a period of 1,500 years by 40 different authors with various backgrounds and cultures, from three continents and three languages, with a variety of literary forms. Yet there is complete unity and harmony which cannot be explained by coincidence. The Bible is unique in its fulfillment of prophecy: The Bible contains over 2,000 statements of prophecy, many of which have occurred just as the Bible predicted. The resettlement of Israel in the Holy Land (Amos 9:14-15), and over 60 details about Jesus’ life (messianic prophecies) – are just a few examples that validate the Bible’s inspiration. -

The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church

Anke Wanger THE-733 1 Student Name: ANKE WANGER Student Country: ETHIOPIA Program: MTH Course Code or Name: THE-733 This paper uses [x] US or [ ] UK standards for spelling and punctuation The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church 1) Introduction The topic of Biblical canon formation is a wide one, and has received increased attention in the last few decades, as many ancient manuscripts have been discovered, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the question arose as to whether the composition of the current Biblical canon(s) should be re-evaluated based on these and other findings. Not that the question had actually been settled before, as can be observed from the various Church councils throughout the last two thousand years with their decisions, and the fact that different Christian denominations often have very different books included in their Biblical Canons. Even Churches who are in communion with each other disagree over the question of which books belong in the Holy Bible. One Church which occupies a unique position in this regard is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church. Currently, it is the only Church whose Bible is comprised of Anke Wanger THE-733 2 81 Books in total, 46 in the Old Testament, and 35 in the New Testament.1 It is also the biggest Bible, according to the number of books: Protestant Bibles usually contain 66 books, Roman Catholic Bibles 73, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles have around 76 books, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on their belonging to the Greek Orthodox, Slavonic Orthodox, or Georgian -

Diocesan Statutes of the Third Diocesan Synod Diocesan Statutes of the Third Diocesan Synod

DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO Diocesan Statutes of the Third Diocesan Synod Diocesan Statutes Diocesan Statutes of the Third Diocesan Synod Promulgated on Th e Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ the King ROMAN CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO The Last Supper, Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO Diocesan Statutes of the Third Diocesan Synod Promulgated on The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ the King NOVEMBER 26, 2006 ROMAN CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO 2110 Broadway, Sacramento, CA 95818-2518 Front cover photo taken by Gino Creglia Photography; photos on inside taken by Cathy Joyce, The Catholic Herald. Rite of Christian Initiation photo, page 43, taken by Julz Hansen. TABLE OF CONTENTS Statute Page Abbreviations iii Pre-Note 2 I. General Norms ......................................................................................... 1-7 6 II. The People of God ................................................................................ 8-72 10 A. The Christian Faithful ............................................................................ 8-16 10 B. The Hierarchical Constitution of the Church 15 Diocesan Bishop and Auxiliary Bishop ............................................... 17-21 15 Priests and Deacons ..........................................................................22-29 17 The Liturgy: Central to the Life of Priests and Deacons .......................30-35 20 Clergy Retreats and Ongoing Education .............................................36-39 22 Conduct of Priests and Deacons ........................................................40-43