“Dark Side”: Star Wars Symbolism and the Acceptance of Torture in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global War on Terror

SADAT MACRO 9/14/2009 8:38:06 PM A PRESUMPTION OF GUILT: THE UNLAWFUL ENEMY COMBATANT AND THE U.S. WAR ON TERROR * LEILA NADYA SADAT I. INTRODUCTION Since the advent of the so-called “Global War on Terror,” the United States of America has responded to the crimes carried out on American soil that day by using or threatening to use military force against Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Pakistan. The resulting projection of American military power resulted in the overthrow of two governments – the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the fate of which remains uncertain, and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq – and “war talk” ebbs and flows with respect to the other countries on the U.S. government’s “most wanted” list. As I have written elsewhere, the Bush administration employed a legal framework to conduct these military operations that was highly dubious – and hypocritical – arguing, on the one hand, that the United States was on a war footing with terrorists but that, on the other hand, because terrorists are so-called “unlawful enemy combatants,” they were not entitled to the protections of the laws of war as regards their detention and treatment.1 The creation of this euphemistic and novel term – the “unlawful enemy combatant” – has bewitched the media and even distinguished justices of the United States Supreme Court. It has been employed to suggest that the prisoners captured in this “war” are not entitled to “normal” legal protections, but should instead be subjected to a régime d’exception – an extraordinary regime—created de novo by the Executive branch (until it was blessed by Congress in the Military * Henry H. -

America's Illicit Affair with Torture

AMERICA’S ILLICIT AFFAIR WITH TORTURE David Luban1 Keynote address to the National Consortium of Torture Treatment ProGrams Washington, D.C., February 13, 2013 I am deeply honored to address this Group. The work you do is incredibly important, sometimes disheartening, and often heartbreaking. Your clients and patients have been alone and terrified on the dark side of the moon. You help them return to the company of humankind on Earth. To the outside world, your work is largely unknown and unsung. Before saying anything else, I want to salute you for what you do and offer you my profound thanks. I venture to guess that all the people you treat, or almost all, come from outside the United States. Many of them fled to America seekinG asylum. In the familiar words of the law, they had a “well-founded fear of persecution”—well- founded because their own Governments had tortured them. They sought refuge in the United States because here at last they would be safe from torture. Largely, they were right—although this morninG I will suGGest that if we peer inside American prisons, and understand that mental torture is as real as physical torture, they are not as riGht as they hoped. But it is certainly true that the most obvious forms of political torture and repression are foreign to the United States. After all, our constitution forbids cruel and unusual punishments, and our Supreme Court has declared that coercive law enforcement practices that “shock the conscience” are unconstitutional. Our State Department monitors other countries for torture. -

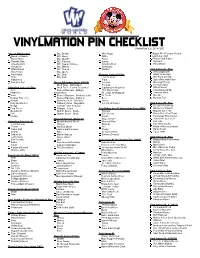

VM Pin Checklist Copy

VINYLMATION PIN CHECKLIST Checklist 1.1 (1/4/15) Alice In Wonderland DCL Dream Miss Piggy Buzz's XP-37 Space Cruiser Queen of Hearts DCL Magic Rizzo Lightning's Bolt Oyster Baby DCL Wonder Rowlf Flowers and Fairies Tweedle Dee DCL Fantasy Statler Figment Tweedle Dum DCL Captain Mickey Swedish Chef Dreamfinder Caterpillar DCL Minnie Sweetums White Rabbit DCL Donald Waldorf Park Series #6 - Pins March Hare DCL Goofy DHS Clapboard Mad Hatter DCL Chip Muppets Series #2 Pins WDW Road Sign Dodo DCL Dale Lew Zealand Wet Paint Donald Hedgehog Pepe Space Mountain Paris Cheshire Cat Disney Afternoon Series 2(2013) Scooter Monorail Orange Duck Tales - Gizmoduck Penguin Sonny Eclipse Animation Series #1 Pins Duck Tales - Fenton Crackshell Captain Link Hogthrob DCL Lifeboat Alice Rescue Rangers - Gadget First Mate Piggy Adventureland Tiki Peter Pan Hackwrench Dr. Julius Strangepork Primeval Whirl Marie Rescue Rangers - Monterey Jack Dr. Teeth Monstro Donkey Pinocchio Rescue Rangers - Zipper Jr. Zoot Norway Troll Aladdin Darkwing Duck - Bushroot Janice Fairy Godmother Darkwing Duck - Negaduck Sgt. Floyd Pepper Park Series #7 - Pins Dodge Talespin - Don Karnage Donald Philharmagic Frog Prince Talespin - Louie Park/Urban Ser. #1 Vinylmation Pins (2008) America on Parade Quasimodo Gummi Bears - Cubbi Figment Muppet Vision 3D Phil Gummi Bears - Gruffi ELP Mickey Tinker Bell’s First Flight Mushu Kermit Polynesian Fire Dancer Haunted Manson Series #1 Magical Stars Figment in Spacesuit Animation Series 2 - 3” Great Ceasar’s Ghost Monorail Red Star Jets Jose Carioca Phineas Teacups Kali River Rapids Flower Hat Box Ghost Yeti World of Motion Serpent Tinker Bell Captain Bartholomew Oopsy Earful Tower Dopey King El Super Raton Epcot 2000 Sebastian Master Gracey Balloon (Chaser) John Henry Singing Bust Park Series #8 - Pins Kim Possible Gus Park Series #2 Vinylmation Pins (2009) Blizzard Beach Snowman Baloo Constance Hatchaway Aquaramouse Buddy Tigger Captain Cullpepper Festival of the Lion King Minnie Moo Fantasia Donald The Executioner Crossroads of the World MK 10th Anniv. -

2018.12.03 Bonner Soufan Complaint Final for Filing 4

Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X : : RAYMOND BONNER and ALEX GIBNEY, Case No. 18-cv-11256 : Plaintiffs, : : -against- : : COMPLAINT CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, : : Defendant. : : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X INTRODUCTION 1. This complaint for declaratory relief arises out of actions taken by defendant Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) that have effectively gagged the speech of former Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) Special Agent Ali Soufan in violation of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The gag imposed upon Mr. Soufan is part of a well-documented effort by the CIA to mislead the American public about the supposedly valuable effects of torture, an effort that has included deceptive and untruthful statements made by the CIA to Executive and Legislative Branch leaders. On information and belief, the CIA has silenced Mr. Soufan because his speech would further refute the CIA’s false public narrative about the efficacy of torture. 2. In 2011, Mr. Soufan published a personal account of his service as a top FBI interrogator in search of information about al-Qaeda before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Soufan’s original manuscript discussed, among other things, his role in the FBI’s interrogation of a high-value detainee named Zayn Al-Abidin Muhammed Husayn, more commonly known as Abu Zubaydah. Soufan was the FBI’s lead interrogator of Zubaydah while he was being held at Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 2 of 19 a secret CIA black site. -

The Taint of Torture: the Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2012 The Taint of Torture: The Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side David Cole Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-054 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/908 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2040866 49 Hous. L. Rev. 53-69 (2012) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Do Not Delete 4/8/2012 2:44 AM ARTICLE THE TAINT OF TORTURE: THE ROLES OF LAW AND POLICY IN OUR DESCENT TO THE DARK SIDE David Cole* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 53 II.TORTURE AND CRUELTY: A MATTER OF LAW OR POLICY? ....... 55 III.ACCOUNTABILITY AND LEGAL VIOLATIONS ............................. 62 IV.THE LAW AND POLICY OF DETENTION AND TARGETING.......... 64 I. INTRODUCTION Philip Zelikow has provided a fascinating account of how officials in the U.S. government during the “War on Terror” authorized torture and cruel treatment of human beings whom they labeled “high value al Qaeda detainee[s],” “enemy combatants,” or “the worst of the worst.”1 Professor Zelikow * Professor, Georgetown Law. 1. Philip Zelikow, Codes of Conduct for a Twilight War, 49 HOUS. L. REV. 1, 22–24 (2012) (providing an in-depth analysis of the decisions made by the Bush Administration in implementing interrogation policies and practices in the period immediately following September 11, 2001); see Military Commissions Act of 2006, Pub. -

• Articles • Across the Star Wars Universe

58 • Articles • Across the Star Wars Universe: A Journey into the World of the Italian Star Wars Fandom GIADA BASTANZI Università Ca’ Foscari of Venice ANDREA FRANCESCHETTI Università Ca’ Foscari of Venice Abstract: In this essay, we perform ethnographic fieldwork on the costuming, prop-making, and performances of the 501st Italica Garrison, the Italian sub-section of the 501st Legion, drawing on the "language" and "speech" theories of Gilbert Ryle and J. N. Findlay (Ryle & Findlay, 1961) and the theoretical position on "strategies" and "tactics" of Michael de Certeau (de Certeau, 2001). While considering the Star Wars franchise and its narratives as a "social phenomenon," we will examine if and how the official Italian fandom’s tactics and performances conform to Henry Jenkins’ concept of "textual poaching" (Jenkins, 2005). In fact, prop-making and collecting performances are in dialectical relation to the narratives of George Lucas, as Lucas’s narratives are in relation to the concepts of Joseph Campbell’s Hero With a Thousand Faces (Campbell, 1949). Vol. 16, no. 1 (2018) New Directions in Folklore 59 Introduction In 2012, LucasFilm Ltd. was purchased by the Disney company. As part of an enormous economic operation, the animation corporation put efforts into broadening the worldwide Star Wars franchise to cultivate the brand and reach more people than ever before. "A long time ago," in 1977, the first film in the franchise, Star Wars: A New Hope was released, creating a generation of fans—and nearly 25 years later, in 2001, The Phantom Menace was released. The new trilogy drew to Star Wars an entirely new generation of fans. -

Star Wars: a New Hope the Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy Pdf

FREE STAR WARS: A NEW HOPE THE PRINCESS, THE SCOUNDREL, AND THE FARM BOY PDF Alexandra Bracken | 336 pages | 22 Sep 2015 | Disney Lucasfilm Press | 9781484709122 | English | United States The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy | Disney Books | Disney Publishing Worldwide Audible Premium Plus. Cancel anytime. Acclaimed New York Times best-selling author Adam Gidwitz delivers a captivating retelling of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back like you've never experienced before, infusing the iconic, classic tale of good versus evil with a unique perspective and narrative style that will speak directly to today's young listeners while enhancing the Star Wars experience for core fans of the saga. By: Adam Gidwitz. Acclaimed New York Times best-selling author Tom Angleberger delivers a captivating retelling of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi like you've never experienced before, infusing the iconic, classic tale of good versus evil with a unique perspective and narrative style that will speak directly to today's young listeners while enhancing the Star Wars experience for core fans of the saga. By: Tom Angleberger. Mischievous and resolved, courageous to the point of recklessness, Anakin Skywalker has come of age in a time of great upheaval. Time has not dulled Anakin's ambition, nor has his Jedi training tamed his independent streak. By: R. In barren desert lands and seedy spaceports At last the saga that captures Star Wars: A New Hope the Princess imagination of millions turns back in time to reveal its cloaked origins - the start of a legend - the story of Star Wars. -

Conflict and Convergence in Legal Education’S Responses to Terrorism

373 The Ivory Tower at Ground Zero: Conflict and Convergence in Legal Education’s Responses to Terrorism Peter Margulies If timidity in the face of government overreaching is the academy’s overarching historical narrative,1 responses to September 11 broke the mold. In what I will call the first generation of Guantánamo issues, members of the legal academy mounted a vigorous campaign against the unilateralism of Bush Administration policies.2 However, the landscape has changed in Guantánamo’s second generation, which started with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Boumediene v. Bush,3 affirming detainees’ access to habeas corpus, and continued with the election of Barack Obama. Second generation Guantánamo issues are murkier, without the clarion calls that marked first generation fights. This Article identifies points of substantive and methodological convergence4 in the wake of Boumediene and President Obama’s election. It then addresses the risks in the latter form of convergence. Substantive points of convergence that have emerged include a consensus on the lawfulness of detention of suspected terrorists subject to judicial review5 and a more fragile meeting of the minds on the salutary role of constraints generally and international law in particular. However, the promise of Peter Margulies is Professor of Law, Roger Williams University. 1. See Sarah H. Ludington, The Dogs that Did Not Bark: The Silence of the Legal Academy During World War II, 60 J. Legal Educ. 396 (2010) (discussing the relative quiescence of legal scholars during the Japanese-American internment and other threats to civil liberties). 2. For a discussion of those policies, see Peter Margulies, Law’s Detour: Justice Displaced in the Bush Administration (NYU Press 2010). -

To Come Jon Favreau Brings the Beloved Hot Summer Characters Back to the Big Screen Blockbusters

Summer 2019 Spring 2019STORIES AND TIPS TO GET THE MOST OUT OF STORIES AND TIPS YOUR REWARDS TO GET THE MOST OUT OF YOUR DISNEY REWARDS COOL OFF WITH Hot Summer Blockbusters COOL OFF WITH THE LION KING RETURNS to come Jon Favreau brings the beloved Hot Summer characters back to the big screen Blockbusters READY, SET, LAUGH WITH TOY STORY 4 Join old friends and new HEAT UP Your Summer Adventures DISCOVER ALADDIN COME TO LIFE See this thrilling adaptation In This Issue Take Imaginations on a Summer Vacation with Your Disney® Visa® Debit Card Summer is a great time to enjoy new PAGES THE TOYS ARE experiences—like the much-anticipated Star PAGES A WHOLE NEW LOOK PAGES STAR WARS: GALAXY’S EDGE 8 & 9 12 & 13 Wars: Galaxy’s Edge opening at Disneyland® 4 & 5 FOR A CLASSIC FILM BACK IN TOWN AT DISNEYLAND® PARK Park on May 31, 2019 (capacity is limited). In Woody, Buzz and the toys hit the road Aladdin comes to life in a brilliant Find helpful hints to make your long-awaited this Rewards insider, you’ll find helpful tips in Toy Story 4, making new friends, new live-action adaptation in journey to Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at for putting your Disney Visa Debit Card to including Forky, a utensil-turned-craft- st theaters May 24th. Disneyland® Park opening May 31 , an work to make the most of this new land. But project-turned-toy. In theaters June 21st. out-of-the-galaxy experience! memorable adventures can also happen at your nearest movie theater. -

Enjoining an American Nightmare

CHAPTER 25 Enjoining an American Nightmare Matthew Harwood n a sweltering Washington, DC, day in late August 2009, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) released a special review from its inspector generalO entitled “Counterterrorism Detention and Interrogation Activities,” dated 7 May 2004.1 The 162-page report, more than five years old by its release, investigated the agency’s use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” (EIT) on high-value al-Qaeda detainees caught by the United States after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. The 10 specific EITs deemed legal by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel for CIA use included stress positions, sleep deprivation, and waterboarding—all commonly considered torture by international law, the human rights community, and the United States prior to 2001.2 Unfortunately, those techniques would finally make their way into mili- tary interrogation rooms in Afghanistan and Iraq, most notoriously Abu Ghraib, in the United States’ Global War on Terror. Despite assurances from the Bush administration that such EITs were legal, the CIA’s inspector general launched the investigation after receiving informa- tion that “some employees were concerned that certain covert agency activities at an overseas detention and interrogation site might involve violations of hu- man rights.”3 The employees worried that CIA interrogators tortured detainees in contravention of United States and international law. Participants in the Counterterrorist Center (CTC) program, responsible for terrorist interroga- tion, damningly told investigators that they feared prosecution for torturing detainees.4 Worse still, the report could not determine whether the enhanced techniques worked, while acknowledging that the techniques’ practitioners knew they could harm the prisoner. -

The Way of Jediism - 1 - Temple of the Jedi Order (Templeofthejediorder.Org) the Way of Jediism

The Way of Jediism - 1 - Temple of the Jedi Order (templeofthejediorder.org) The Way of Jediism First Edition Published by the Temple of the Jedi Order (TOTJO) First International Church of Jediism (charter received Dec 25th 2005) www.TempleOfTheJediOrder.org All content is copyrighted to the Temple of the Jedi Order and the relevant authors, July 2010. Edited by John Henry Phelan (Patriarch/President/Senior Pastor), Mark Barwell (Cardinal Bishop/VP/Associate Pastor) and Hans Thomas Finch. Front cover courtesy of Alejandro Mascaro (Knight of Jediism at the Temple of the Jedi Order) The Way of Jediism - 2 - Temple of the Jedi Order (templeofthejediorder.org) Table of Contents Jediism – a 21st Century Paradigm.................................................................3 Jedi Doctrine as defined by the Temple of the Jedi Order...............................6 Becoming a Jedi...............................................................................................8 16 Basic Teachings of the Jedi........................................................................8 The Jedi Creed...............................................................................................10 The Orthodox Jedi Code................................................................................11 3 Primary Tenets of Jediism...........................................................................11 Jedi Oaths......................................................................................................12 The 12 Vows of the Jedi.................................................................................12 -

The Star Wars Timeline Gold: Appendices 1

The Star Wars Timeline Gold: Appendices 1 THE STAR WARS TIMELINE GOLD The Old Republic. The Galactic Empire. The New Republic. What might have been. Every legend has its historian. By Nathan P. Butler - Gold Release Number 49 - 78th SWT Release - 07/20/11 _________________________________________ Officially hosted on Nathan P. Butler’s website __at http://www.starwarsfanworks.com/timeline ____________ APPENDICES ―Look at the size of that thing!‖ --Wedge Antilles Dedicated to All the loyal SWT readers who have helped keep the project alive since 1997. -----|----- -Fellow Star Wars fans- Now that you‘ve spent time exploring the Star Wars Timeline Gold‘s primary document and its Clone Wars Supplement, you‘re probably curious as to what other ―goodies‖ the project has in store. Here, you‘ll find the answer to that query. This file, the Appendices, features numerous small sections, featuring topics ranging from G-Canon, T-Canon, and Apocryphal (N-Canon) timelines, a release timeline for ―real world‖ Star Wars materials, information relating to the Star Wars Timeline Project‘s growth, and more. This was the fourth file created for the Star Wars Timeline Gold. The project originally began as the primary document with the Official Continuity Timeline, then later spawned a Fan Fiction Supplement (now discontinued) and an Apocrypha Supplement (now merged into this file). The Appendices came next, but with its wide array of different features, it has survived to stand on its own alongside the primary document and continues to do so alongside the newer Clone Wars Supplement. I hope you find your time spent reading through it well spent.