Contempt by Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique and Comment Reform of the Judicial Appointments Process

—M.U.L.R— DavisWilliams — Title of Article — printed 14/12/03 at 12:53 — page 819 of 45 CRITIQUE AND COMMENT REFORM OF THE JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS PROCESS: GENDER AND THE BENCH OF THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ∗ RACHEL DAVIS AND GEORGE WILLIAMS† [The judges of the High Court of Australia are appointed by the federal executive on the basis of ‘merit’ after an informal and secret consultation process. This system is anachronistic when compared with the judicial appointments procedures and ongoing reforms in other common law jurisdictions, and when considered against the minimum level of scrutiny and accountability now expected of senior appointments to other public institutions. It is also inconsistent with the role of the High Court in determining the law, including matters of public policy, for the nation as a whole. One consequence of the current system, including its reliance on the subjective concept of ‘merit’, is that, of the 44 appointments to the Court, only one has been a woman. The appointments process should be reformed to provide for the selection of High Court judges by the executive based upon known criteria after the preparation of a short list by a judicial appointments commission. Without this, the current executive appointments system threatens to undermine public confidence in the Court and the administration of justice.] CONTENTS I Introduction.............................................................................................................820 II The Current Executive Appointments Process........................................................823 -

Bench & Bar Dinner

CONTENTS Winter 2001 Editor’s note . 2 Letters to the Editor. 3 A message from the President . 4 Editorial Board Justin Gleeson S.C. (Editor) Recent developments Andrew Bell Two recent High Court decisions . 8 James Renwick Reinsurance recoveries . 11 Rena Sofroniou Melway and Boral considered. 13 Chris Winslow (Bar Association) Opinion Criminal prosecutions . 20 Editorial Print/Production To specialise or not to specialise?. 22 Rodenprint Interview Paul Daley: 40 years not out . 24 Layout Hartrick’s Design Office Pty Ltd Bench & Bar Dinner 2001 . 30 Advertising Addresses Bar News now accepts The Hon. Bob Debus MP . 32 advertisements. For more 37 information, contact The Hon. Justice D A Ipp. Chris Winslow at the Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. 41 NSW Bar Association on (02) 9229 1732 or e-mail Features [email protected] Pacific Circuit . 43 Duty Barrister Scheme. 45 Cover A portrait of Ian Barker QC, Tribute entered in the 2001 Archibald Competition by artist Deny Jennifer Blackman: A tribute . 47 Christian. The artist was previously the winnerof the Appointments 'Packers' Prize' in 1999. The Hon. Justice McClellan . 48 The Hon. Justice Palmer . 48 The Hon. Justice Allsop . 49 The Hon. Justice Stevenson . 50 ISSN 0817-002 Vale Bertram Wright QC . 51 Views expressed by contributors to Bar Hugh Robson QC . 51 News are not necessarily those of the Bar The Hon. Russell Bainton QC. 52 Association of NSW. Patrick Costello . 53 Michael Errington . 55 Contributions are welcome and should be addressed to the Editor, Justin Mariusz Podleska . 55 Gleeson S.C., 7th Floor, Wentworth John Evans . 54 Chambers, 180 Phillip Street, Sydney, NSW 2000. -

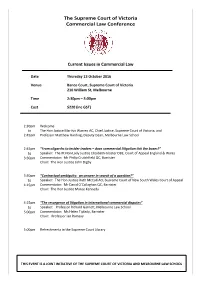

2016 Conference Program

The Supreme Court of Victoria Commercial Law Conference Current Issues in Commercial Law Date Thursday 13 October 2016 Venue Banco Court, Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William St, Melbourne Time 2:30pm – 5:00pm Cost $220 (inc GST) 2:30pm Welcome to The Hon Justice Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Victoria, and 2:45pm Professor Matthew Harding, Deputy Dean, Melbourne Law School 2:45pm “From oligarchs to insider traders – does commercial litigation tick the boxes?” to Speaker: The Rt Hon Lady Justice Elizabeth Gloster DBE, Court of Appeal England & Wales 3:30pm Commentator: Mr Philip Crutchfield QC, Barrister Chair: The Hon Justice John Digby 3:30pm “Contractual ambiguity: an answer in search of a question?” to Speaker: The Hon Justice Ruth McColl AO, Supreme Court of New South Wales Court of Appeal 4:15pm Commentator: Mr David O’Callaghan QC, Barrister Chair: The Hon Justice Maree Kennedy 4:15pm “The resurgence of litigation in international commercial disputes” to Speaker: Professor Richard Garnett, Melbourne Law School 5:00pm Commentator: Ms Helen Tiplady, Barrister Chair: Professor Ian Ramsay 5:00pm Refreshments in the Supreme Court Library THIS EVENT IS A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA AND MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Session 1 The Right Hon Dame Elizabeth Gloster DBE PC, was appointed a Lady Justice of Appeal, and consequently appointed to the Privy Council, on 9 April 2013. Dame Elizabeth was called to the Bar by the Inner Temple in 1971; in 1989 she was appointed a Queen's Counsel and made a Bencher of the Inner Temple in 1992. -

The Honourable Justice M J Beazley AO*

99 Judicial Officers’ Bulletin Published by the Judicial Commission of NSW December 2018, Volume 30 No 11 100 years of women in the law The Honourable Justice M J Beazley AO* To acknowledge the centenary of the Women’s Legal Status Act 1918, which allowed women to practise law in NSW, the President of the Court of Appeal reflects on the slow acceptance of women into the legal profession and some of the trailblazing women who “did it first”. On 5 December 1918, the NSW legislature passed the stipendiary or police magistrate, or a justice of the peace; or Women’s Legal Status Act 1918 (NSW) (the Act). The Act was admitted and to practise as a barrister or solicitor of the NSW the culmination of protracted lobbying by women activists of Supreme Court, or to practise as a conveyancer. the time, including the English suffragette Adela Pankhurst, who visited Sydney in 1914, sisters Belle and Annie Goldring, Sixty-two years later, in 1980, Jane Mathews became the Rose Scott and Kate Dwyer. A Bill was originally introduced first woman to be appointed to the NSW District Court. into the NSW Legislative Assembly in August 1916, but She was only the second woman to have been appointed a withdrawn as it was ruled out of order. A second Bill lapsed. judge in Australia. Dame Roma Mitchell was the first, having The Women’s Legal Status Bill was eventually introduced been appointed to the South Australian Supreme Court in on 3 October 1918 by the NSW Attorney General and 1965. It is perhaps unsurprising that South Australia was the barrister, David Hall. -

Summer Edition

SUMMER EDITION A brief meditation on artificial intelligence Guidance for NSW Barristers in the wake of lawyer X Updated sentencing statistics on the Judicial Information Research System CONTENTS THE JOURNAL OF THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2019 02 EDITOR’S NOTE bar 04 PRESIDENT’S COLUMN news 06 OPINION ws The bar needs to fight for its future 6 The future of the Bar – a response 8 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE A brief meditation on artificial intelligence, Ingmar Taylor SC (Chair) adjudication and the judiciary 10 ne Gail Furness SC The consequence of delay in Local Court criminal matters 13 Anthony Cheshire SC Farid Assaf SC 14 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS Dominic Villa SC THE JOURNAL OF NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | AUTUMN 2019 14 Penny Thew Scrutinising Two-Candidate Preferred Counting in the High Court Daniel Klineberg Australian Securities and Investments Commission bar Catherine Gleeson v Kobelt [2019] HCA 18 16 Victoria Brigden Claims for quantum meruit 18 Kevin Tang Belinda Baker Female Genital Mutilation and Statutory Construction 20 Stephen Ryan A Majority of the Victorian Court of Appeal Uphold Cardinal Joe Edwards Pell’s Conviction for Child Sexual Assault Offences 22 Sean O'Brien Kavita Balendra The UK Supreme Court finds that Boris Johnson’s Ann Bonnor prorogation of Parliament was unlawful 24 Christina Trahanas Trouble in Paradise Papers: privilege may not found a cause of action 26 Bar Association staff members: Michelle Nisbet Vale the Chorley Exception 27 Cover image: Rocco Fazzari 28 FEATURES Guidance for NSW Barristers 28 ISSN 0817-0002 A Message from the Free State of Prussia to Hong Kong 30 Views expressed by contributors 34 to Bar News are not necessarily Are there implications of New South Wales Court filing trends? those of the New South Wales The updated and enhanced sentencing statistics on Bar Association.