Unionized Charter School Contracts As a Model for Reform of Public School Job Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections-2016.Pdf

2016 UNITED FEDERATION OF TEACHERS • RETIRED TEACHERS CHAPTER INTRODUCTION It is always a pleasure to experience the creativity, insights and talents of our re- tired members, and this latest collection of poems and writings provides plenty to enjoy! Being a union of educators, the United Federation of Teachers knows how im- portant it is to embrace lifelong learning and engage in artistic expression for the pure joy of it. This annual publication highlights some gems displaying the breadth of intellectual and literary talents of some of our retirees attending classes in our Si Beagle Learning Centers. We at the UFT are quite proud of these members and the encouragement they receive through the union’s various retiree programs. I am happy to note that this publication is now celebrating its 23rd anniversary as part of a Retired Teachers Chapter tradition reflecting the continuing interests and vitality of our retirees. The union takes great pride in the work of our retirees and expects this tradition to continue for years to come. Congratulations! Michael Mulgrew President, UFT Welcome to the 23rd volume of Reflections in Poetry and Prose. Reflections in Poetry and Prose is a yearly collection of published writings by UFT retirees enrolled in our UFTWF Retiree Pro- grams Si Beagle Learning Center creative writing courses and retired UFT members across the country. We are truly proud of Reflections in Poetry and Prose and of the fine work our retirees do. Many wonderful, dedicated people helped produce this volume of Reflections in Poetry and Prose. First, we must thank the many contributors, UFT retirees, many of whom participated in the creative writing classes at our centers, and also our learning center coordinators, outreach coordi- nators and instructors who nurture talent and encourage creative expression. -

AGREEMENT Between the United States Postal Service And

AGREEMENT Between the United States Postal Service and the American Postal Workers Union, AFL-CIO Covering Information Technology/Accounting Services 2011-2016 AGREEMENT Between the United States Postal Service and the American Postal Workers Union, AFL-CIO Covering Information Technology/Accounting Services 2011– 2016 UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE 2011 IT/AS NEGOTIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Subject Page Preamble 1 Article 1 Union Recognition 2 Article 2 Non-Discrimination and Civil Rights 3 Article 3 Management Rights 4 Article 4 Technological and Mechanization Changes 5 Article 5 Prohibition of Unilateral Action 7 Article 6 No Layoffs or Reduction in Force 8 Article 7 Employee Classifications 9 Article 8 Hours of Work 11 Article 9 Salaries and Wages 15 Article 10 Leave 1 8 Article 11 Holidays 2 1 Article 12 Probationary Period 2 4 Article 13 Assignment of Ill or Injured Regular Work Force Employees 25 Article 14 Safety and Health 2 7 Article 15 Grievance-Arbitration Procedure 30 Article 16 Discipline Procedure 35 Article 17 Representation 39 Article 18 No Strike 44 Article 19 Handbooks and Manuals 45 Article 20 Parking 46 Article 21 Benefit Plans 47 Article 22 Bulletin Boards 49 Article 23 Rights of Union Officials to Enter Postal Installations 50 Article 24 Employees on Leave with Regard to Union Business 51 Article 25 Higher Level Assignments 52 iii Subject Page Article 26 Work Clothes 54 Article 27 Employee Claims 55 Article 28 Employer Claims 56 Article 29 Training 57 Article 30 Local Working Conditions 5 8 Article 31 Union-Management -

The Middle School Teacher Turnover Project

The Research Alliance for New York City Schools Executive Summary February 2011 The Middle School Teacher Turnover Project A Descriptive Analysis of Teacher Turnover in New York City’s Middle Schools William H. Marinell The Research Alliance for New York City Schools Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development Acknowledgements While there is one author listed on the title page of this report, many individuals contributed to this report and to the analyses on which it is based. James Kemple, the Executive Director of the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, provided invaluable guidance about the design and execution of the analyses, as well as thoughtful and thorough critique of drafts of this report and its accompanying Executive Summary and Technical Appendix. Jessica Lent, Janet Brand, and Micha Segeritz, all Research Alliance colleagues, provided critical analytical and data management support at various points. The members of our larger research team – Richard Arum (NYU), Aaron Pallas (Teachers College, Columbia), Jennifer Goldstein (Baruch College, CUNY) and doctoral students Amy Scallon, Travis Bristol, and Barbara Tanner – contributed constructive feedback throughout the analytical process. Jim Wyckoff, Sean Corcoran, and Morgaen Donaldson offered candid, extremely valuable critique of the study’s technical and substantive merits, as did the New York City Department of Education’s research team led by Jennifer Bell-Ellwanger. Members of the Research Alliance’s Governance Board identified findings that might resonate with various stakeholders in the New York City public education system. Research Alliance staff members Lori Nathanson, Tom Gold, Adriana Villavicencio, and Jessica Lent helped revise this report and its accompanying documents. -

New York City Rubber Rooms: the Legality of Temporary Reassignment Centers in the Context of Tenured Teachers’ Due Process Rights

NEW YORK CITY RUBBER ROOMS: THE LEGALITY OF TEMPORARY REASSIGNMENT CENTERS IN THE CONTEXT OF TENURED TEACHERS’ DUE PROCESS RIGHTS By Bree Williams Education Law & Policy Professor Kaufman May 14, 2009 1 I. INTRODUCTION Jago Cura, a 32 year-old English teacher, was three months into his teaching assignment in the New York City Public School District (“the District”) when he was assisting students in his class with a group project.1 For no discernible reason, he began to lose control of his students and the class environment turned chaotic.2 Unable to deal with the stress, Cura began screaming and cursing at his students and, shortly after that, picked up a chair and flung it toward a blackboard.3 The chair bounced off the blackboard and grazed a student.4 After a moment, Cura realized what he had done and left the classroom.5 The day after this incident, the principal of Cura’s school instructed him to go to a Department of Education building for work instead of his classroom to teach.6 Unbeknownst to him at the time, Cura was being sent to a Temporary Reassignment Center, or what teachers within the District have termed, a “rubber room.”7 Rubber rooms are Department of Education facilities throughout the District that serve as a type of holding facility where teachers awaiting investigations or hearings involving alleged mishaps are sent for an indefinite period of time. This paper analyzes the legality of rubber rooms as a form of re-assignment for teachers that have allegedly engaged in misconduct, in light of a teacher’s tenure rights and right of due process. -

28Th SEASON ANNUAL REPORT

28th SEASON ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 LA RUTA by Ed Cardona, Jr., Directed by Tamilla Woodard Set Design by Raul Abrego, Costume Design by Emily DeAngelis, Lighting Design by Lucrecia Briceño, Sound Design by Sam Kusnetz, Projection Design by Dave Tennent & Kate Freer, IMA, Prop Design by Claire Kavanah Above: Annie Henk, Zoë Sophia Garcia, Gerardo Rodriguez, and Bobby Plasencia Left: Brian D. Coats and Sheila Tapia Cover: the set of LA RUTA Photos © Lia Chang, 2013 CONTENTS Letter from the Producing Artistic Director 4 Community Outreach & Events 6 TheaterWorks! 7 La Ruta 8 Directors Salon 12 2013 Annual Awards Ceremony 14 Financials 15 Supporters 16 Board & Staff 18 Working Theater is dedicated to producing new plays for and about working people.* Our 28th Season ran from February to June 2013 and featured the development and production of several new plays, as well as other events aimed specifically at reaching our audience of working men and women. *working people refers to the wage and salaried workers of modest means working in factories, stores, offices, hospitals, classrooms and other workplaces throughout America. A note from the PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Working Theater’s 2012/13 Season was without a doubt one of the most extraordinary seasons in our history. Several years back Working Theater held a day-long retreat with its board and staff to assess the Company’s progress in achieving its mission: to create theater for and about working people and introduce audiences of working people (the doormen, postal workers, bus drivers, city employees and restaurant workers who make NYC run) to the intimate thrill and transformation of off-Broadway Theater. -

THE NEW YORK CITY DEPAR1MENT of EDUCATION April 15, 2010 Michael Mulgrew, President United Federation of Teachers 52 Broadway, 1

THE NEW YORK CITY DEPAR1MENT OF EDUCATION JOEL I. KLEIN. Cliana{fo, OFACE OF THE CHANCELLOR 52 CHAMBERS STREET - NEW YORK NY 10007 April 15, 2010 Michael Mulgrew, President United Federation ofTeachers 52 Broadway, 14th Floor New York, New York 10004 Dear Mr. Mulgrew: This letter will confirm the mutual understandings and agreements between the Board of Education ofthe City School District ofthe City ofNew York ("DOE") and the United Federation ofTeachers ("UFT"). Nothing in this Agreement shall constitute a waiver or modification ofany provision ofany collective bargaining agreement, letter (including but not limited to the June 27, 2008 letter from the Chancellor to the President ofthe UFT) or other agreement between the DOE and the UFT except as specifically set forth herein. Nothing in this agreement shall be construed to convert non-mandatory subjects ofbargaining into mandatory subjects ofbargaining. As used herein, the term "CBA" shall refer to the collective bargaining agreement covering teachers and corresponding provisions ofother UFT-DOE collective bargaining agreements. The long delays that have arisen in the current process ofinvestigating alleged acts of misconduct and adjudicating charges pursuant to Education Law § 3020-a benefit neither the DOE nor the employees represented by the UFT. The DOE and the UFT are committed to ensuring that the agreements reached here will be carried out so that those delays will be ended and the process outlined in the law, the contracts between the parties, and this Agreement will be adhered to. For purposes ofthis Agreement, all timelines shall be measured in calendar days, but shall not include the summer break, all recess periods and holidays. -

Chapter Leader Handbook 2015 UNITED FEDERATION of TEACHERS Local 2, American Federation of Teachers AFL-CIO

MICHAEL MULGREW, PRESIDENT Chapter Leader Handbook 2015 UNITED FEDERATION OF TEACHERS Local 2, American Federation of Teachers AFL-CIO 52 Broadway New York, NY 10004 1-212-777-7500 OFFICERS MICHAEL MULGREW…………………………………...…..………. President EMIL PIETROMONACO……………………………………………… Secretary LEROY BARR………….………………..………………… Assistant Secretary MEL AARONSON…………………………..………………………… Treasurer TOM BROWN…………………………………………….... Assistant Treasurer VICE PRESIDENTS KAREN ALFORD …..………...……....………...…….…. Elementary Schools CARMEN ALVAREZ ………..……………........………….. Special Education EVELYN DEJESUS ………..….………………………........ Education Issues ANNE GOLDMAN …………..…………...…………….… Non-DOE Members JANELLA HINDS …………...…………….……..….. Academic High Schools RICHARD MANTELL ....................... Junior High and Intermediate Schools STERLING ROBERSON … Career and Technical Education High Schools UFT BOROUGH OFFICES Bronx: 2500 Halsey St. ………….………………..….……….. 1-718-379-6200 Brooklyn: 335 Adams St., 25th Floor …………………...……. 1-718-852-4900 Manhattan: 52 Broadway ……………………….…………..... 1-212-598-6800 Queens: 97-77 Queens Boulevard ……………..………..….. 1-718-275-4400 Staten Island: 4456 Amboy Rd., 2nd Floor ……..……….…... 1-718-605-1400 Dear Colleagues, It is with great pride and gratitude that I write this letter. Chapter leaders are the backbone of our union. It is you, the union’s frontline representatives, who know best what is happening in the schools; you who can report how budget cuts, principals and everything else are really affecting students and educators; and you who motivate and mobilize UFT members into the powerful force that we are. There is no more important job in our union, and I thank you for taking it on. The union has put together this manual to help you in that job. It contains a “how-to” section that gives an overview of the many roles chapter leaders play and several sections that provide a comprehensive breakdown of everything you need to know about union benefits, the grievance process, salary schedules and much more. -

Studentsfirstny Analyzes Hidden 2015-16 Teacher Evaluation Ratings

BURYING THE EVIDENCE: StudentsFirstNY Analyzes Hidden 2015-16 Teacher Evaluation Ratings At a recent meeting, New York City United Federation of Teachers (UFT) President Mike Mulgrew crowed that 97% of city teachers are effective or highly effective according to the 2016-17 evaluation results. The problem is, there has been no public review of the results from the 2015-16 school year, let alone the newer results the union boss touted. A deliberate attempt to de-emphasize teacher evaluation results While the New York State Education Department (SED) produced an analysis of the results in March and posted it on the website, there was no public release, and no mention of the analysis in any Board of Regents meetings. Five months later, again with no press release, SED posted researcher files with the 2015-16 data, away from view of most parents and education stakeholders. Several weeks later, some data was posted in a more parent-friendly format, but a query for New York City results produces an error message. SED displayed an alarming lack of transparency by failing to properly release a detailed analysis of 2015-16 teacher evaluation ratings. Some might argue that these ratings have less meaning since there’s a moratorium on the use of student test scores and evaluations are in a transitional state. In this paper, StudentsFirstNY argues the opposite: it is because evaluations are in a state of transition that we must closely analyze the results to have an informed conversation on what is working and what is not. Regents Chancellor Betty Rosa recently told POLITICO New York, “We’re going to take stock in the next month or two before the Legislature comes back,” but she had already concluded that the moratorium must be extended, without any public review of the latest results. -

Com·Mu·Ni·Ty /K-´Myü-N-Te¯/ a Unified Body of Individuals Working Together

Strengthening our communities com·mu·ni·ty /k-´myü-n-te¯/ A unified body of individuals working together. Getting to know the United Federation of Teachers The UFT represents over 200,000 members — New York City public school teachers, paraprofessionals, guidance counselors, social workers, psychologists, school secretaries, nurses, administrative law judges and family child care providers, just to name a few. un·ion /´yoon-y ne / The act of joining together for a common purpose. Michael Mulgrew President UFT Vice Presidents BOROUGH OFFICES Queens Michael Mendel Secretary Carmen Alvarez Bronx 97-77 Queens Blvd. Mel Aaronson Treasurer Karen Alford 2500 Halsey Street Rego Park, NY 11374 Bronx, NY 10461 718.275.4400 Robert Astrowsky Assistant Secretary Leo Casey 718.379.6200 Mona Romain Assistant Treasurer Richard Farkas Staten Island Brooklyn 4456 Amboy Road Catalina Fortino 335 Adams Street Staten Island, NY Sterling Roberson Brooklyn, NY 11201 10312 Anthony Harmon Director of Community 718.852.4900 718.605.1400 & Parent Engagement Manhattan 52 Broadway New York, NY 10004 212.598.6800 Part of your community For over fifty years, the United Federation of Teachers has committed itself to strengthening our communities, our schools and the lives of our students. Through their hard work and dedication, UFT members are making the city a better place to live and work every day. e /k me -´pa -SH n/ com·pas·sion The act of helping others, especially those who are struggling. Paraprofessionals Family Child Care Providers Nurses Teachers Helping students succeed – In the classroom and beyond Each and every student deserves a quality education and the opportunity to succeed. -

Nycdoe-09X313-Is-313-School-Of-Leadership

June 24, 2015 To Whom It May Concern: The New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) intends to submit applications for the School Improvement Grant (SIG) Cohort 6 to the New York State Department of Education (NYSED). The NYCDOE currently intends to submit applications for the following six (6) schools with the following intervention models: DBN School Name BEDS Code Intervention Model 30Q111 PS 111 JACOB BLACKWELL 343000010111 Innovation Framework 07X520 FOREIGN LANG ACAD OF GLOBAL STUDIES 320700011520 Innovation Framework 14K322 FOUNDATIONS ACADEMY 331400011322 Innovation Framework 16K455 BOYS AND GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 331600011455 Innovation Framework 25Q460 FLUSHING HIGH SCHOOL 342500011460 Innovation Framework 09X313 IS 313 SCHOOL OF LEADERSHIP DEV 320900010313 Innovation Framework We may also submit additional applications; we are currently finalizing the selection of any other schools and intervention models. Please feel free to contact us with questions. Thank you for this opportunity to support our schools. Sincerely, Mary Doyle Executive Director State School Improvement & Innovation Grants Office of State/Federal Education Policy & School Improvement Programs [email protected] 2015 SIG 6 Application Cover Page Last updated: 06/18/2015 Please complete all that is required before submitting your application. Page 1 Select District (LEA) Name: Listed alphabetically by District 320900010000 NYC GEOG DIST # 9 - BRONX Select School Name: Listed alphabetically by school name (Priority Schools followed by Focus Schools) 320900010313 -

Signed Order

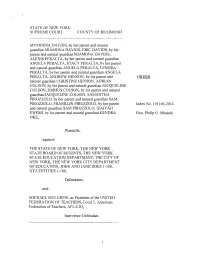

STATE OF NEW YORK SUPREME COURT COUNTY OF RICHMOND MYMOENA DAVIDS, by her parent and natural guardian MIAMONA DAVIDS, ERIC DAVIDS, by his parent and natural guardian MIAMONA DAVIDS, ALEXIS PERALTA, by her parent and natural guardian ANGELA PERALTA, STACY PERALTA, by her parent and natural guardian ANGELA PERALTA, LENORA PERALTA, by her parent and natural guardian ANGELA PERALTA, ANDREW HENSON, by his parent and ORDER natural guardian CHRISTINE HENSON, ADRIAN COLSON, by his parent and natural guardian JACQUELINE COLSON, DARIUS COLSON, by his parent and natural guardian JACQUELINE COLSON, SAMANTHA PIROZZOLO, by her parent and natural guardian SAM PIROZZOLO, FRANKLIN PIROZZOLO, by her parent Index No. 101105-2014 and natural guardian SAM PIROZZOLO, IZAIYAH EWERS, by his parent and natural guardian KENDRA Hon. Philip G. Minardo OKE, Plaintiffs, -against- THE STATE OF NEW YORK, THE NEW YORK STATE BOARD OF REGENTS, THE NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, THE CITY OF NEW YORK, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, JOHN AND JANE DOES 1-100, XYZ ENTITIES 1-100, Defendants, -and- MICHAEL MULGREW, as President ofthe UNITED FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, Local 2, American Federation ofTeachers, AFL-CIO, Intervenor-Defendant. SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF RICHMOND JOHN KEONI WRIGHT, GINET BORRERO, TAU ANA GOINS, NINA DOSTER, CARLA WILLIAMS, MONA PRADIA, ANGELES BARRAGAN, Plaintiffs, -against- THE STATE OF NEW YORK, THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, MERRYL H. TISCH, in her official capacity as Chancellor ofthe Board of Regents ofthe University of the State of New York, JOHN B. -

Campaign Highlights Parent Rights

SPECIAL POST-RA EDITION n Delegates set union’s course | 10 n Union celebrates award winners | 14 www.nysut.org | May 2017 THIS ISSUE OF NYSUT UNITED CONTAINS INFORMATION REGARDING THE NYSUT MEMBER BENEFITS SUMMARY ANNUAL REPORT. Campaign NYSUT President highlights Andy Pallotta and his team parent rights | 6 get down to work | 6 NYSUT members receive a 20% discount off of tuition for Advance your career graduate courses. ELT is now a CTLE provider and many courses are applicable for With NYSUT ELT: NYSED Certification • learn research-based, class- • collaborate with fellow educators room tested, methods in our across New York state — seminars and/or graduate online or site-based! courses; Your choice. Your professional • meet certification requirements; learning. Register and online www.nysut.org/elt To Register: www.nysut.org/elt • 800.528.6208 Be a fan. NYSUT Affiliated with AFT n NEA n AFL-CIO NYSUT UNITED [ MAY 2017, Vol. 7, No. 5 ] NEW YORK STATE UNITED TEACHERS Catanzariti (Retiree), Thomas Murphy (Retiree) Director of Communications: Member Records Department 800 Troy-Schenectady Road, Latham, NY 12110 Deborah Hormell Ward 800 Troy-Schenectady Road, Latham, NY 12110 AT-LARGE DIRECTORS: Cheryl Hughes, 518-213-6000 n 800-342-9810 Editor-in-Chief: Mary Fran Gleason Joseph Cantafio, Rick Gallant, John Kozlowski, Kevin PERIODICALS POSTAGE PAID AT LATHAM, NY Copy Desk Chief: Clarisse Butler Banks OFFICERS: Ahern, Don Carlisto, Maria Pacheco, Raymond ADDITIONAL ENTRY OFFICE WILLIAMSPORT, PA 17701 President: Andy Pallotta Hodges, Pat Puleo, Selina Durio, Edward Vasta, Assistant Editors/Writers: Leslie Duncan Fottrell, Liza Frenette, Ned Hoskin, Executive Vice President: Jolene T.