Alternative Agenda for Rewriting the History of the Iviarathas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government College of Engineering, Karad

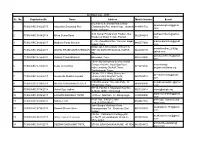

Government College of Engineering Karad An Autonomous Institute of Government of Maharashtra Vidyanagar, Karad, Maharashtra 415124, India Student List Degree : B.TECH. Semester : V Branch : CIVIL ENGINEERING Sr No Application ID Reg No Student Name 1 EN18139966 18111101 SATHE RUTUJA AVINASH 2 EN17115475 17111204 JATHAR GANESH DNYANDEV 3 EN18154858 18111205 BANSODE VINAY BHAGWAN 4 EN17123894 17111206 VALAY RAMESHWAR NIRMAL 5 EN18191091 18111206 DHAWALE GHANSHYAM KISHOR 6 EN18157253 18111208 SHETAKE MANOJ MOHAN 7 EN18216384 18111209 SUTAR RATAN MAHADEV 8 EN18196991 18111110 ADHORE YOGITA NAVNATH 9 EN18163148 18111111 DESAI RUTUJA ANIL 10 EN18208965 18111212 VINAYAK BAPUSAHEB SALUNKHE 11 EN18144709 18111213 KUNAL MURLIDHAR PAWAR 12 EN18143224 18111214 NARALE AUDUMBAR PRAKASH 13 EN18197088 18111215 OSWAL KHETAL JEEVAN 14 EN18130505 18111217 BHAGWAT OMKAR BHIMRAO 15 EN18197281 18111118 PATIL VISHAKHA SHANKARRAO 16 EN18193439 18111219 POWAR ANKIT MADHUKAR 17 EN18192291 18111220 SHEVADE SHREYASH DILIP 18 EN18125595 18111221 GOMASE YASH DIWAKAR 19 EN18158032 18111124 KAMBLE DIPTI SHIVAJI 20 EN18106023 18111225 SWAMI SUSMIT MANTAYYA 21 EN18217870 18111227 TINGARE KIRTIRAJ MAHESH 22 EN17211607 17111128 KAMBLE SAMIKSHA GARIBDAS 23 EN18115778 18111229 GORE VISHAL BABURAO 24 EN18211196 18111230 PATIL CHINMAY MARUTI 25 EN18187113 18111231 WAGHMARE VIKRAM DHANRAJ 26 EN18193917 18111233 KHUPERKAR SWARUP SARJERAO 27 EN18238676 18111134 KSHIRSAGAR SONALI SHAHAJI 28 EN18216513 18111139 NAIK AKSHATA PRAKASH 29 EN18235638 18111140 ASMITA ARJUN OHOL 30 EN18160710 -

A/C Ahshivrad Water Supplayers Vele Mu.Po.Vele Ta.Vai A/C Babu Rajan T

Janata Urban Co-Operative Bank Ltd.,Wai Unclaimed Deposit upto Jan 2016 NAME ADDRESS A/C AHSHIVRAD WATER SUPPLAYERS VELE MU.PO.VELE TA.VAI A/C BABU RAJAN T. A/P SURUR A/C BAGAL KIRAN ANIL A.P.K. A/P SURUR A/C BAGAL RANGUBAI NARAYAN A/P SURUR A/C BALAG UDDHAV VISHWANATH MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C BANDAL VITTHAL ANANDRAO MU.MOHDEKRVADI PO.SURUR A/C BHOSALE CHANDRAKANT DHARMU MU.PO.SHIRAGAV TA.VAI A/C BHUMI AGRO INDUSTRIES A/P BHUINJ A/C BULUNGE BABURAO LAXMAN MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C BULUNGE RAJENDRA VITTHAL MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C C.K. ARFAT MOYADU MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C C.K. MUSTAK MOYADU MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C C.K. SIBU NANU MU.PO.VELE TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C CHANDELIYA SUKHADEV MUKNARAM A/P SURUR A/C CHAVAN AVINASH PRATAPRAO A/P SURUR A/C CHAVAN BALKRUSHNA BABURAO MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C CHAVAN CHAYADEVI ARVIND (2) AT-PO-SURUR, A/C CHAVAN DHANSING NIVRUTTI MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C CHAVAN GAJANAN DYANDEV A/P SURUR A/C CHAVAN HANAMANT KRUSHNA A/P-SURUR A/C CHAVAN INDUBAI MARUTI MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C CHAVAN MADHAVRAO YADAVRAO MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C CHAVAN MARUTI SHAMRAO MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C CHAVAN SARSWATI BAJIRAO MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C CHAVAN SHAKUNTALA NARAYAN MU.PO.SURUR A/C CHOUHAN KHERU LAXMAN AT-PO-GULUMB,TAL-WAI, A/C DERE RAJENDRA VINAYAK MU.PO.VELE TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C DERE VINAYAK SHRIRANG MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C DHAMAL ANIL GAJABA MU.PO.VELE TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C DHAYAGUDE MOHAN NAMADEV MU.VADACHAMLA PO.KHED TA.KHAND A/C DHEVAR BALDRUSHNA DHONDIBA A/P SURUR A/C DHIVAR JITENDRA DHONDIBA MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI A/C DHUMAL VASANT DINKAR AT-WAHAGAON,PO-SURUR, A/C DIPNARAYANSIGHN DUKHANSIGH MU.PO.SURUR TA.VAI JI.SATARA A/C GAIKWAD ANUSAYA DADASO A/P-VELE TAL-WAI Page 1 Janata Urban Co-Operative Bank Ltd.,Wai Unclaimed Deposit upto Jan 2016 A/C GAIKWAD BALKRUSHNA MUGUTRAO AT-PO-SURUR, A/C GAIKWAD SUREKHA SUNIL MUA.PO.KAVTHE TA.VAI. -

Shivaji the Founder of Maratha Swaraj

26 B. I. S. M. Puraskrita Grantha Mali, No. SHIVAJI THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ BY C. V. VAIDYA, M. A., LL. B. Fellow, University of Bombay, Vice-Ctianct-llor, Tilak University; t Bharat-Itihasa-Shamshndhak Mandal, Poona* POON)k 1931 PRICE B8. 3 : B. Printed by S. R. Sardesai, B. A. LL. f at the Navin ' * Samarth Vidyalaya's Samarth Bharat Press, Sadoshiv Peth, Poona 2. BY THE SAME AUTHOR : Price Rs* as. Mahabharat : A Criticism 2 8 Riddle of the Ramayana ( In Press ) 2 Epic India ,, 30 BOMBAY BOOK DEPOT, BOMBAY History of Mediaeval Hindu India Vol. I. Harsha and Later Kings 6 8 Vol. II. Early History of Rajputs 6 8 Vol. 111. Downfall of Hindu India 7 8 D. B. TARAPOREWALLA & SONS History of Sanskrit Literature Vedic Period ... ... 10 ARYABHUSHAN PRESS, POONA, AND BOOK-SELLERS IN BOMBAY Published by : C. V. Vaidya, at 314. Sadashiv Peth. POONA CITY. INSCRIBED WITH PERMISSION TO SHRI. BHAWANRAO SHINIVASRAO ALIAS BALASAHEB PANT PRATINIDHI,B.A., Chief of Aundh In respectful appreciation of his deep study of Maratha history and his ardent admiration of Shivaji Maharaj, THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ PREFACE The records in Maharashtra and other places bearing on Shivaji's life are still being searched out and collected in the Shiva-Charitra-Karyalaya founded by the Bharata- Itihasa-Samshodhak Mandal of Poona and important papers bearing on Shivaji's doings are being discovered from day to day. It is, therefore, not yet time, according to many, to write an authentic lifetof this great hero of Maha- rashtra and 1 hesitated for some time to undertake this work suggested to me by Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Prati- nidhi, Chief of Aundh. -

Shivaji's Fortunes and Possessions

The Life of Shivaji Maharaj, 414-420, 2017 (Online Edition). N. Takakhav Chapter 31 Shivaji’s Fortunes and Possessions N. S. Takakhav Professor, Wilson College, Bombay. Editor Published Online Kiran Jadhav 17 March 2018 The life story of Shivaji has been told in the preceding chapters. It is proposed in the present chapter to make an attempt to estimate the extent of his power, possessions and wealth at the time of his death. Nor should it be quite an uninteresting subject to make such an audit of his wealth and possessions, seeing that it furnishes an index to the measure of his success in his ceaseless toils of over thirty-six years, in that war of redemption which he had embarked upon against the despotism of the Mahomedan rulers of the country. At the time when the Rajah Shahaji transferred his allegiance from the fallen house of the Naizam Shahi sultans to that of the still prosperous Adil Shahi dynasty and in the service of that government entered upon the sphere of his proconsular authority in the Karnatic, he had left his Maharashtra jahgirs, as we have seen, under the able administration of the loyal Dadaji Kondadev. These jahgir estates comprised the districts of Poona, Supa, Indapur, Daramati and a portion of the Maval country. This was the sole patrimony derived by Shivaji from his illustrious father at the time he embarked upon his political career. Even these districts were held on the sufferance of the Bijapur government and were saddled with feudal burdens. That government was in a position to have cancelled or annexed these jahgirs at any time. -

THE SWAMI at DHAYAD3HI. the Chhatrapati the Peshwa Iii) The

156 CHAPTER lY : THE SWAMI AT DHAYAD3HI. i) The Chhatrapati ii) The Peshwa iii) The Nobility iv) The Dependents. V) His iiind* c: n .. ^ i CHAPTER IV. THE SWAia AT DHAVADSHI, i) The Chhatrapatl* The eighteenth century Maratha society was religious minded and superstitious. Ilie family of the Chhatrapati was n6 exception to this rule. The grandmother of the great Shivaji, it is said, had vowed to one pir named Sharifji.^ Shivaji paid homage to the Mounibawa of - 2 Patgaon and Baba Yakut of Kasheli. Sambhaji the father of Shahu respected Ramdas. Shahu himself revered Sadhus and entertained them with due hospitality. It is said that Shahu»s concubine Viroobai was dearer to him than his two (^eens Sakwarbai and Sagimabai. Viroobai controlled all Shahu*s household matters. It is 1h<xt said/it was Viroobai who first of all came in contact with the Swami some time in 1715 when she had been to the Konkan for bathing in the sea and when she paid a visit to Brahmendra Swami.^ The contact gradually grew into an intimacy. As a result the Sv/ami secured the villages - 1. SMR Purvardha p . H O 2. R.III 273. 3. HJlDH-1 p. 124. 158 Dhavadshi, Virmade and Anewadi in 1721 from Chhatrapati dhahu. Prince Fatesing»s marriage took place in 1719. life do not find the name of the Swami in the list of the invitees,^ which shows that the Swami had not yet become very familiar to the King, After the raid of Siddi Sad on Parshurajs the Swami finally decided to leave Konkan for good. -

The History of the Royal Family Hh

THE HISTORY OF THE ROYAL FAMILY H.H. Kshatriya Kulawatasana, Sinhasanadhishwar Shrimant Raja Shivaji IV [Baba Sahib] Bhonsle Chhatrapati Maharaj 1838 - 1866 H.H. Kshatriya Kulawatasana, Sinhasanadhishwar Shrimant Raja Shivaji IV [Baba Sahib] Bhonsle Chhatrapati Maharaj Shahaji Dam Altaphoo, Raja of Kolhapur, KCSI (24.5.1866). b. at the Sarnobat Mansion, 26th December 1830, eldest son of H.H. Kshatriya Kulawatasana, Sinhasanadhishwar Shrimant Raja Shahaji I [Buwa Sahib] Bhonsle Chhatrapati Maharaj, Raja of Kolhapur, by his fourth wife, H.H. Shrimant Akhand Soubhagyavati Anandi Bai Tara Sahib Maharaj, educ. privately. Succeeded on the death of his father, 29th November 1838. Ascended the gadi, 13th December 1838 and reigned under a Council of Regency until he came of age. Invested with full ruling powers, 1866. m. (first) at Kolhapur, 26th April 1847, H.H. Shrimant Akhand Soubhagyavati Sundra Bai Sahib Maharaj (b. 1835; d. at Kolhapur, 21st December 1866), daughter of Meherban Shrimant Khasajirao Sahib Patankar, of Patan. m. (second) at Baroda, 17th May 1854, H.H. Shrimant Akhand Soubhagyavati Rani Ahilya Bai Barodekarin Sahib Maharaj [Khasai Bai] (b. at the Royal Palace, Baroda, 1842; d. at Kolhapur, 14th December 1895), daughter of H.H. Shrimant Maharaja Ganpatrao Gaekwad, Sena Khas Khel Shamsher Bahadur, Maharaja of Baroda. He d. at the Old Palace, Kolhapur, 4th August 1866, having had issue three sons: * 1) Yuvraj Shrimant Shahaji [Bala Sahib] Maharaj. b. at Kolhapur, 24th August 1848 (s/o Sundra Bai). He d. March 1849. * 2) An unnamed son of Sundra Bai. b. at Kolhapur, 13th November 1855 and d. 26th May 1857. -

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Middle Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP.ID-CL.ID. Account No. Invest Type Amount Transferred Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF PAN Number Aadhar Number 74/153 GANDHI NAGAR A ARULMOZHI NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 636102 IN301774-10480786-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 160.00 15-Sep-2019 ATTUR 1/26, VALLAL SEETHAKATHI SALAI A CHELLAPPA NA KILAKARAI (PO), INDIA Tamil Nadu 623517 12010900-00960311-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 60.00 15-Sep-2019 RAMANATHAPURAM KILAKARAI OLD NO E 109 NEW NO D A IRUDAYAM NA 6 DALMIA COLONY INDIA Tamil Nadu 621651 IN301637-40636357-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 KALAKUDI VIA LALGUDI OPP ANANDA PRINTERS I A J RAMACHANDRA JAYARAMACHAR STAGE DEVRAJ URS INDIA Karnataka 577201 IN300360-10245686-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 8.00 15-Sep-2019 ACNPR4902M NAGAR SHIMOGA NEW NO.12 3RD CROSS STREET VADIVEL NAGAR A J VIJAYAKUMAR NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 632001 12010600-01683966-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 15-Sep-2019 SANKARAN PALAYAM VELLORE THIRUMANGALAM A M NIZAR NA OZHUKUPARAKKAL P O INDIA Kerala 691533 12023900-00295421-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 AYUR AYUR FLAT - 503 SAI DATTA A MALLIKARJUNAPPA ANAGABHUSHANAPPA TOWERS RAMNAGAR INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 IN302863-10200863-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 80.00 15-Sep-2019 AGYPA3274E -

List of Employees in Bank of Maharashtra As of 31.07.2020

LIST OF EMPLOYEES IN BANK OF MAHARASHTRA AS OF 31.07.2020 PFNO NAME BRANCH_NAME / ZONE_NAME CADRE GROSS PEN_OPT 12581 HANAMSHET SUNIL KAMALAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 13840 MAHESH G. MAHABALESHWARKAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 14227 NADENDLA RAMBABU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 14680 DATAR PRAMOD RAMCHANDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182116.67 PENSION 16436 KABRA MAHENDRAKUMAR AMARCHAND AURANGABAD ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 168872.35 PENSION 16772 KOLHATKAR VALLABH DAMODAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 16860 KHATAWKAR PRASHANT RAMAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 183517.13 PENSION 18018 DESHPANDE NITYANAND SADASHIV NASIK ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169370.75 PENSION 18348 CHITRA SHIRISH DATAR DELHI ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 166230.23 PENSION 20620 KAMBLE VIJAYKUMAR NIVRUTTI MUMBAI CITY ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169331.55 PENSION 20933 N MUNI RAJU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 172329.83 PENSION 21350 UNNAM RAGHAVENDRA RAO KOLKATA ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 21519 VIVEK BHASKARRAO GHATE STRESSED ASSET MANAGEMENT BRANCH GENERAL MANAGER 160728.37 PENSION 21571 SANJAY RUDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182204.27 PENSION 22663 VIJAY PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 179765.67 PENSION 11631 BAJPAI SUDHIR DEVICHARAN HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13067 KURUP SUBHASH MADHAVAN FORT MUMBAI DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13095 JAT SUBHASHSINGH HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13573 K. ARVIND SHENOY HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 164483.52 PENSION 13825 WAGHCHAVARE N.A. PUNE CITY ZONE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 155576.88 PENSION 13962 BANSWANI MAHESH CHOITHRAM HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 14359 DAS ALOKKUMAR SUDHIR Retail Assets Branch, New Delhi. -

Architect List - 2019 Sr

Architect List - 2019 Sr. No. RegistrationNo Name Address Mobile Number E-mail 642,Flat no 9, Snehal Park,Behind splusadesigners@gmail. 1 PCMC/ARC/0652/2017 Adityasinh Dayanand Patil Chandrakant Patil Heart Hosp. Jawahar 8149991732 com Nagar, Kolhapur. A/16 Kumar Priydarshan Pashan, Sus subhaarchitects@yahoo. 2 PCMC/ARC/0438/2018 Milind Subha Saraf 9822554283 Road,near Balaji Temple Pashan com C - 16, Jivandhara Soc. Yamuna nagar, madhuraarchitect@gmail. 3 PCMC/ARC/0692/2017 Madhura Parag Merukar 9860577999 Nigadi- Pune com SHOP NO 1,SHIVANJALI HEIGHTS anandkhedkar_2000@ 4 PCMC/ARC/0562/2017 ANAND PRABHAKAR KHEDKAR BEHIND BORATE SANKUL KARVE 9822400439 yahoo.com RD. sucratuarchitects@gmail. 5 PCMC/ARC/0725/2018 Siddesh Pravin Bhansali Bibvewadi, Pune. 9028783400 com 1901/1902 Drewberry Everest World Complex Kolshet Road,Opp Bayer kedar.bhat@ 6 PCMC/ARC/0768/2018 Kedar Arvind Bhat 9819519195 India Company Dhokali,Thane, srujanconsultants.org Sandozbaugh Thane. Flat no. 102 J- Wing, Survey no directionnextds@gmail. 7 PCMC/ARC/0682/2017 Amannulla Shabbir Inamdar 5A/2A,212B/2, Mayfair Pacific, 9657009789 com Kondhawa Khurd Pune,NIBM C/O-AR.Laxman Thite Sita Park, 18, milind.laxmanthite@gmail 8 PCMC/ARC/0399/2018 MILIND RAMCHANDRA PATIL 8408880898 Shivajinagar, Pune .com RH 55, Flat No 8, Nityanand Hsg Soc, 9 PCMC/ARC/0718/2018 Vishal Vijay Jadhav 9923128414 [email protected] G-Block, MIDC, Chinchwad datta.laxmanthite@gmail. 10 PCMC/ARC/0532/2017 LAXMAN SADASHIV THITE 1st Floor, Sita Park, 18, Shivajinagar, 8408880890 com PLOT NO - 390,SECTOR archetype_associates@ 11 PCMC/ARC/0074/2017 Nafisa A Kazi 9922007885 27/A,PCNTDA,NIGDI gmail.com Janiv Bangla Malshiras Road swapnilgirme173@gmail. -

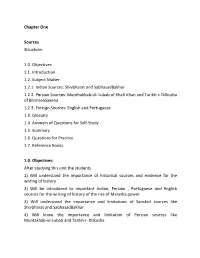

Chapter One Sources Structure: 1.0. Objectives 1.1. Introduction 1.2. Subject Matter 1.2.1. Indian Sources: Shivbharat and Sabha

Chapter One Sources Structure: 1.0. Objectives 1.1. Introduction 1.2. Subject Matter 1.2.1. Indian Sources: Shivbharat and SabhasadBakhar 1.2.2. Persian Sources: Munthakhab-ul- Lubab of Khafi Khan and Tarikh-i- Dilkusha of BhimsenSaxena 1.2.3. Foreign Sources: English and Portuguese 1.3. Glossary 1.4. Answers of Questions for Self-Study 1.5. Summary 1.6. Questions for Practice 1.7. Reference Books 1.0. Objectives: After studying this unit the students 1) Will understand the importance of historical sources and evidence for the writing of history 2) Will be introduced to important Indian, Persian , Portuguese and English sources for the writing of history of the rise of Maratha power. 3) Will understand the importance and limitations of Sanskrit sources like Shivbharat and SabhasadBakhar. 4) Will know the importance and limitation of Persian sources like Muntakhab-ul-Lubab and Tarikh-i- Dilkusha 5) Know the value of documents in English and Portuguese languages for writing the history of Marathas. They will also know about the places where these documents are preserved. 1.1. Introduction: Historical sources are any traces of the past that remain. They may be written sources, documents, newspapers, laws, literature and diaries. They may be artifacts, sites, buildings. History is written with the help of these sources. Whatever the historian says or writes is based on the information and evidence provided by the sources. The historian gathers his information and evidence about the past events and culture by studying the historical sources. It is only by using this collected information that the historian can narrate the history of past events and individuals. -

Maharashtra Council of Homoeopathy 235, Peninsula House, Above Sbbj Bank, 3Rd Floor, Dr

MAHARASHTRA COUNCIL OF HOMOEOPATHY 235, PENINSULA HOUSE, ABOVE SBBJ BANK, 3RD FLOOR, DR. D.N. ROAD, FORT, MUMBAI- 400001 MAHARASHTRA STATE HOMOEOPATHY PRACTITIONER LIST Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. EMAIL ID Remarks 1 CHUGHA TEJBHAN B 9/27, KRISHNA NAGAR Male DEFAULTER GOPALDAS P.O.GANDHI NAGAR, DELHI-51 NAME REMOVED DELHI DELHI 2 ATHALYE VASUDEO 179, BHAWANI PETH Male DEFAULTER VISHVANATH SARASWATI SADAN NAME REMOVED SATARA MAHARASHTRA 3 KUNDERT ABRAHAM 2,RAVINDRA BHUVAN DR. Male DEFAULTER CHANDRASHEKARA AMBEDKAR ROAD,KHAR NAME REMOVED 400052 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 4 PINTO LAWRENCE 22/23 IBRAHIM COURT ST.PAUL Male DEFAULTER MARTIN BALTAZAR ST.NAIGAUM DADAR, NAME REMOVED 400014 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 5 CHUGHA CAMP 180, SHREE NAGAR Male DEFAULTER PRAKASHCHANDRA COLONY INDORE I.M.P. PRAKASHCHANDRA COLONY INDORE I.M.P. NAME REMOVED BHANJANRAM MADHYA PRADESH 6 SHAIKH MEHBOOB ABBAS CHAKAN,TALUKA-KHED Male DEFAULTER NAME REMOVED PUNE MAHARASHTRA 7 PARANJPE MORESHWAR 1398,SADASHIV PETH, POONA Male DEFAULTER NARAYAN NAME REMOVED PUNE MAHARASHTRA 8 CAPTAIN COWAS CAPTAIN VILLA,4, BANDRA HILL, Male DEFAULTER CURSETJI MT.MARY RD NAME REMOVED MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 9 GUPTA KANTILAL C/O DR.P.C.CHUGHA RAVAL Male DEFAULTER SOHANLAL BLDG.LAMINGTON RD NAME REMOVED 400007 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 10 MENDONCA BLANCHEDE 19,ST.FRANCIS AVENUE, Female DEFAULTER WELLINGDON SOUTH NAME REMOVED SANTACRUZ, 400054 MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 11 HATTERIA HOMEE SIR.SHAPURJI BHARUCHA BAUG Male DEFAULTER ARDESHIR SORABJI PLOT NO.L, FLAT NO.4 NAME REMOVED GHODBUNDER -

1 2 3 4 5 6 1 1 Padegaon Shri Dhaygude Talathi 7770089649 2 2

Both Level Officer (BLO) Information Name of 255 Phaltan (SC) Assembly Constituency BLO Information Sr.No Polling Name Of Polling Name Of BLO Designation Mobile No. Station No. Station 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 1 Padegaon Shri Dhaygude Talathi 7770089649 2 2 Padegaon Smt.Gharule Anganvadi Sevika 9623032141 3 3 Padegaon S.R.Raut Gramsevak 9822350526 4 4 Padegaon Smt.L.K.Borate Anganvadi Sevika 9011530446 5 5 Kusur Shri Tanaji Kumbhar Agri Asst 9270335417 6 6 Mirewadi Smt.L.R.Khude Gramsevika 9404386820 7 7 Rawadi Bk. Shri D.M.Madane Agri Asst 9420764644 8 8 Rawadi Ku. Shri.H.R.Raykar Gramsevak 9890155627 9 9 Hol Sou.V.P.Jagtap Anganvadi Sevika 9960908766 10 10 Hol Sou.V.S.Puri Anganvadi Sevika 7709845265 11 11 Jinti Shri.R.B.Ingale Talathi 9158146364 12 12 Jinti Sou.S.D.Ranware Anganvadi Sevika 9561469780 13 13 Jinti Shri.G.M.Jadhav` Gramsevak 9922643015 14 14 Pimpalwadi Shri.S.N.Ahivale Talathi 9822756266 15 15 Pimpalwadi P.E.Yele Gramsevak 9561896687 16 16 Pimpalwadi Sou.R.S.Dhaygude Anganvadi Sevika 9970891431 17 17 Sakhawadi Sou.K.B.Bhosale Anganvadi Sevika 7790663400 18 18 Sakhawadi D.B.Bodare Grampanchyat Clerk 9766890282 19 19 Sakhawadi Sou.S.R.Malvadkar Anganvadi Sevika 9765066899 20 20 Sakhawadi Sou.V.S.Fadtare Anganvadi Sevika 8796941268 21 21 Sakhawadi Sou.S.V.Kakade Anganvadi Sevika 8796941268 22 22 Khamgaon R.D.Kale Talathi 9421389053 23 23 Khamgaon Sou.S.V.Vare Anganvadi Sevika 9860745739 24 24 Khamgaon Sarkal Shri.D.D.Nimbalkar Gramsevak 7588638325 25 25 Khamgaon Sarkal H.M.Devare Anganvadi Sevika 9881817150 26 26 Murum G.B.Khomane Gramsevak 9850467430 27 27 Shindemal Shri.N.D.Adsul Primary Teacher 9922643119 28 28 Malewadi Shri.G.K.Adsul Primary Teacher 9922643119 9673624129 29 29 Koregaon Smt.