Santa Clara County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Study Appendix B

Uvas Road at Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project Biological Assessment Biological Assessment Uvas Road over Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (37C-0095/37C-0601 [new]) Near Morgan Hill, Santa Clara County, California 04-SCL-0-CR Federal Project Number BRLO 5937(124) Caltrans District 04 November 2015 Biological Assessment Uvas Road over Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (37C-0095/37C-0601 [new]) Near Morgan Hill, Santa Clara County, California 04-SCL-0-CR Federal Project Number BRLO 5937(124) Caltrans District 04 November 2015 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Department of Transportation and Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department Prepared By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Patrick Boursier, Principal (408) 458-3204 H. T. Harvey & Associates Los Gatos, California Approved By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Solomon Tegegne, Associate Civil Engineer Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department Highway and Bridge Design 408-573-2495 Concurred By: ___________________________________ Date: ____________ Tom Holstein Environmental Branch Chief Office of Local Assistance Caltrans, District 4 Oakland, California 510-286-5250 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in Braille, large print, on audiocassette, or computer disk. To obtain a copy in one of these alternate formats, please call or write to the Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department: Solomon Tegegne Santa Clara County Roads and Airports Department 101 Skyport Drive San Jose, CA 95110 408-573-2495 Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Determinations Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Determinations The Uvas Road at Little Uvas Creek Bridge Replacement Project (proposed project) is proposed by the County of Santa Clara Roads and Airports Department in cooperation with the Office of Local Assistance of the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and this Biological Assessment (BA) has been prepared following Caltrans’ procedures. -

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015 I. Introduction The Board of Directors (“Board”) has requested information relating to facility operations at the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range (“Chabot Gun Range” or “gun range”), including estimated capital and operation and maintenance costs required for continued operation of the gun range. As discussed below, District staff has gathered information regarding environmental compliance, facility conditions and deferred maintenance, sound impacts and mitigation options, and information related to use, revenue, and operational costs of the gun range. II. CEQA Compliance No action by the Board is being requested at this time, and therefore no action is necessary to comply with CEQA for purposes of this Board item. However, a decision by the Board to consider entry into a long term extension of the Chabot Gun Club’s lease would first require environmental review under CEQA, most likely the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR). III. History of the Chabot Gun Range In 1963, the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range was developed in cooperation with the Oakland Pistol Club, which had previously leased a site in Knowland Park, Oakland, California. The original 1962 lease was a partnership between the District and the Oakland Pistol Club to construct, develop, operate and maintain a marksmanship range in Anthony Chabot Regional Park. In 1964, the original lease was amended to finalize the schedule and define the cost-share for construction of the Chabot Gun Range. In 1967, the District entered into a new long-term lease with Chabot Gun Club, Inc. -

Do No R Resource G Uide

H Reaching for the Stars… Continuing the Legacy www.csecc.org “You have the opportunity to brighten lives with your generosity to your favorite charities. Join Maria and me and become someone's star by participating in the 2008 California State Employees Charitable Campaign.” donor resource guide resource donor A RN OLD S CHWARZENEGGER Governor of California 2008 California State Employees Charitable Campaign Chair H H Chair’s Message H Dear Fellow State Employees, It is a big thrill to be back as chairman of the 2008 California State Employees Charitable Campaign. I enjoyed last year’s campaign so much that I couldn’t wait to get started again. Together, we raised $8.7 million for our favorite charities. I am proud to say this was the most we’ve ever raised and the biggest annual increase in the history of the campaign. It was truly a fantastic year, and working with so many wonderful and compassionate volunteers was a tremendous inspiration. In fact, my belief that Californians are the most generous people in the world is stronger than ever, and I know that we can set the bar even higher this year. Thank you for all of your great work, and I look forward to another record-breaking campaign. Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor 2008 CSECC Chair 2 H California State Employees Charitable Campaign H Table of Contents H United Way Organizations (PCFDs) .....................9 America’s Charities ........................................................... 33 Arrowhead United Way ........................................................ 9 Animal Charities of America .............................................. 34 United Way of the Bay Area ................................................. 9 Arts Council Silicon Valley ..................................................35 United Way of Butte & Glenn Counties ................................12 Asian Pacific Community Fund of Southern California ..........35 United Way California Capital Region ..................................13 Bay Area Black United Fund, Inc. -

Spring 2020 News

Spring 2020 News We are Different. We are Able. Mission CAA provides an equitable collegiate experience to adults with special needs who historically have not had access to college education. Students Bernard and Frank in our new computer lab Vision CAA Classes go online during Shelter in Place Empowering the student body When the shelter in place mandate was put in with Joint Venture Silicon Valley to secure to creatively transform the way place March 2020 there was one week left in the community volunteers to help CAA students the world views individuals quarter. In the last week of the Winter Quarter, and families with their new distance learning with disabilities. CAA creates CAA transitioned to a fully online learning equipment. successful contributing citizens platform, and we have Michael Reisman, Director through the arts. CAA student ambassador Oliver M. was able to of the School of Science and Technology, and Dr. give Mayor Sam Liccardo a CAA Visionary Award Motto Pamela Lindsay, Dean of Instruction, to thank. the day the Mayor Zoomed in to be interviewed by Showcase Ability! They worked tirelessly researching Zoom and the CAA podcasting class. establish links that the students would use. They Founders Executive Board also wrote and published instructions for accessing CAA extends to the entire community heartfelt Dr. Pamela Lindsay, EdD/CI Ali Barekat each of the 58 courses. thanks for your support and goodwill during these DeAnna Pursai, Exec. Dir. Reverend David Bird times. Communication, teamwork, and a steadfast Board of Directors David Cross Spring Quarter resumed on Monday, April 6. CAA desire to give adults of all abilities a chance to Leann Cherkasky-Makhni Piero Dusa welcomed ten new students. -

AQ Conformity Amended PBA 2040 Supplemental Report Mar.2018

TRANSPORTATION-AIR QUALITY CONFORMITY ANALYSIS FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Commission Association of Bay Area Governments MARCH 2018 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Jake Mackenzie, Chair Dorene M. Giacopini Julie Pierce Sonoma County and Cities U.S. Department of Transportation Association of Bay Area Governments Scott Haggerty, Vice Chair Federal D. Glover Alameda County Contra Costa County Bijan Sartipi California State Alicia C. Aguirre Anne W. Halsted Transportation Agency Cities of San Mateo County San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission Libby Schaaf Tom Azumbrado Oakland Mayor’s Appointee U.S. Department of Housing Nick Josefowitz and Urban Development San Francisco Mayor’s Appointee Warren Slocum San Mateo County Jeannie Bruins Jane Kim Cities of Santa Clara County City and County of San Francisco James P. Spering Solano County and Cities Damon Connolly Sam Liccardo Marin County and Cities San Jose Mayor’s Appointee Amy R. Worth Cities of Contra Costa County Dave Cortese Alfredo Pedroza Santa Clara County Napa County and Cities Carol Dutra-Vernaci Cities of Alameda County Association of Bay Area Governments Supervisor David Rabbit Supervisor David Cortese Councilmember Pradeep Gupta ABAG President Santa Clara City of South San Francisco / County of Sonoma San Mateo Supervisor Erin Hannigan Mayor Greg Scharff Solano Mayor Liz Gibbons ABAG Vice President City of Campbell / Santa Clara City of Palo Alto Representatives From Mayor Len Augustine Cities in Each County City of Vacaville -

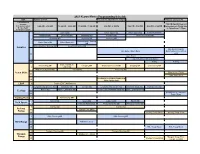

2021 Camp Keowa Master Programming Schedule

2021 Keowa Master Programming Schedule KEY Update: 2/17/21 ←Lunch 12:15pm/Siesta 1:00pm ←Dinner Lineup 5:45 I = instructional program 7:00 PM (Spirit Program) O = open program 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM 10:00 AM - 10:50 AM 11:00 AM - 11:50 AM 2:00 PM - 2:50 PM 3:00 PM - 3:50 PM 4:00 PM - 4:50 PM No program on Friday due B = bookable to Campfire at 7:30pm A = Adult Program BSA Guard Water Sports MB Water Sports MB Instructional Swim Swimming MB Swimming MB Swimming MB Kayaking MB Small Boat Sailing MB Lifesaving MB Kayaking MB Canoeing MB I Motor Boating / Rowing Water Sports MB Water Sports MB MB Aquatics Motor Boating / Rowing MB Small Boat Sailing MB Mile Swim/ Rowing Mile Swim (Thurs Only) Qualifications (Tues/Wed O only) Open Swim Open Boating (ends at 4:30pm) B Tubing Tubing Signs, Signals, & Geocaching MB Camping MB Wilderness Survival MB Camping MB Orienteering MB I Codes MB Wilderness Survival MB First Aid MB Pioneering MB Scout Skills Firem'n Chit (Thurs) O Totin' Chip (Tues) Introduction to Outdoor Leadership A Skills (Adults Only) LEAF I Project LEAF (AM Session) Envionmental Science MB Astronomy MB Forestry MB Environmental Science MB Mammal Study MB Plant Science MB I Ecology Nature MB Space Exploration MB Reptile and Amphibian Study MB Space Exploration MB Introduction to Leave No O Trace (Tues) Trading Post I Salemanship MB Fishing MB Sports MB Athletics MB Sports MB Field Sports I Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB I Archery MB Archery MB Archery O Archery Free Shoot Range B Archery Troop Shoot Archery -

'An Incredibly Vile Sport': Campaigns Against Otter Hunting in Britain

Rural History (2016) 27, 1, 000-000. © Cambridge University Press 2016 ‘An incredibly vile sport’: Campaigns against Otter Hunting in Britain, 1900-39 DANIEL ALLEN, CHARLES WATKINS AND DAVID MATLESS School of Physical and Geographical Sciences, University of Keele, ST5 5BG, UK [email protected] School of Geography, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Otter hunting was a minor field sport in Britain but in the early years of the twentieth century a lively campaign to ban it was orchestrated by several individuals and anti-hunting societies. The sport became increasingly popular in the late nineteenth century and the Edwardian period. This paper examines the arguments and methods used in different anti-otter hunting campaigns 1900-1939 by organisations such as the Humanitarian League, the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports and the National Association for the Abolition of Cruel Sports. Introduction In 2010 a painting ‘normally considered too upsetting for modern tastes’ which ‘while impressive’ was also ‘undeniably "gruesome"’ was displayed at an exhibition of British sporting art at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. The Guardian reported that the grisly content of the painting was ‘the reason why it was taken off permanent display by its owners’ the Laing Gallery in Newcastle.1 The painting, Sir Edwin Landseer’s The Otter Speared, Portrait of the Earl of Aberdeen's Otterhounds, or the Otter Hunt had been associated with controversy since it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844 Daniel Allen, Charles Watkins and David Matless 2 (Figure 1). -

1982 Flood Report

GB 1399.4 S383 R4 1982 I ; CLARA VAltEY WATER DISlRIDl LIBRARY 5750 ALMADEN EXPRESSYIAY SAN JOSE. CAUFORN!A 9Sll8 REPORT ON FLOODING AND FLOOD RELATED DAMAGES IN SANTA CLARA COUNTY January 1 to April 30, 1982 Prepared by John H. Sutcliffe Acting Division Engineer Operations Division With Contributions From Michael McNeely Division Engineer Design Division and Jeanette Scanlon Assistant Civil Engineer Design Division Under the Direction of Leo F. Cournoyer Assistant Operations and Maintenance Manager and Daniel F. Kriege Operations and Maintenance Manager August 24, 1982 DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS Arthur T. Pfeiffer, Chairman District 1 James J. Lenihan District 5 Patrick T. Ferraro District 2 Sio Sanchez. Vice Chairman At Large Robert W. Gross District 3 Audrey H. Fisher At large Maurice E. Dullea District 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCrfION .......................... a ••••••••••••••••••• 4 •• Ill • 1 STORM OF JANUARY 3-5, 1982 .•.•.•.•.•••••••.••••••••.••.••.••.••••. 3 STORMS OF MARCH 31 THROUGH APRIL 13, 1982 ••.....••••••.•••••••••••• 7 SUMMARY e • • • • • • • • • : • 111 • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1111 o e • e • • o • e • e o e • e 1111 • • • • • e • e 12 TABLES I Storm Rainfall Summary •••••••••.••••.•••••••.••••••••••••• 14 II Historical Rainfall Data •••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 15 III Channel Flood Flow Summary •••••.•••••.•••••••••••••••••••• 16 IV Historical Stream flow Data •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 17 V January 3-5, 1982 Damage Assessment Summary •••••••••••••••••• 18 VI March 31 - April 13, 1982 Damage -

Disaster Declarations in California

Disaster Declarations in California (BOLD=Major Disaster) (Wildfires are Highlighted) 2018 DR-4353 Wildfires, Flooding, Mudflows, And Debris Flows Declared on Tuesday, January 2, 2018 - 06:00 FM-5244 Pawnee Fire Declared on Sunday, June 24, 2018 - 07:11 FM-5245 Creek Fire Declared on Monday, June 25, 2018 - 07:11 2017 DR-4301 Severe Winter Storms, Flooding, and Mudslides Declared on Tuesday, February 14, 2017 - 13:15 EM-3381 Potential Failure of the Emergency Spillway at Lake Oroville Dam Declared on Tuesday, February 14, 2017 - 14:20 DR-4302 Severe Winter Storm Declared on Tuesday, February 14, 2017 - 14:30 DR-4305 Severe Winter Storms, Flooding, and Mudslides Declared on Thursday, March 16, 2017 - 04:48 DR-4308 Severe Winter Storms, Flooding, Mudslides Declared on Saturday, April 1, 2017 - 16:55 DR-4312 Flooding Declared on Tuesday, May 2, 2017 - 14:00 FM-5189 Wall Fire Declared on Sunday, July 9, 2017 - 14:18 FM-5192 Detwiler Fire Declared on Monday, July 17, 2017 - 19:23 DR-4344 Wildfires Declared on Tuesday, October 10, 2017 - 08:40 2016 FM-5124 Old Fire Declared on Saturday, June 4, 2016 - 21:55 FM-5128 Border 3 Fire Declared on Sunday, June 19, 2016 - 19:03 FM-5129 Fish Fire Declared on Monday, June 20, 2016 - 20:35 FM-5131 Erskine Fire Declared on Thursday, June 23, 2016 - 20:57 FM-5132 Sage Fire Declared on Saturday, July 9, 2016 - 18:15 FM-5135 Sand Fire Declared on Saturday, July 23, 2016 - 17:34 FM-5137 Soberanes Fire Declared on Thursday, July 28, 2016 - 16:38 FM-5140 Goose Fire Declared on Saturday, July 30, 2016 - 20:48 -

National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Weekend October 3-4, 2015

Remembering ver in Our Hea Fore rts ® National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Weekend Weekend Memorial Firefighters Fallen National 2015 ® National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Post Office Drawer 498 National Fallen Firefighters Emmitsburg, Maryland 21727 Memorial Weekend 301.447.1365 • 301.447.1645 fax www.firehero.org • [email protected] October 3-4, 2015 matt Ambelas • David Wilbur Anderson • Thomas Araguz III • Samir P. “Sam” Ashmar • matt Ambelas • David Wilbur Anderson • Thomas Araguz III • Samir P. “Sam” Ashmar • Gregory D. Barnas • Jeffery Edward Bayless • Kevin L. Bell • James E. Bethea • Joseph Gregory D. Barnas • Jeffery Edward Bayless • Kevin L. Bell • James E. Bethea • Joseph Edward Bove III • Kevin J. Bristol • Bruce Britt • John M. Burns • Jerry Campbell • Paul S. Edward Bove III • Kevin J. Bristol • Bruce Britt • John M. Burns • Jerry Campbell • Paul S. Cash • Douglas J. Casson • Dennis A. Channell • Richard L. Choate • Joyce M. Craig • Cash • Douglas J. Casson • Dennis A. Channell • Richard L. Choate • Joyce M. Craig • James A. Dickman • Ricky W. Doub • Ted F. Drake • Fred Edwards • Hugh B. Ferguson James A. Dickman • Ricky W. Doub • Ted F. Drake • Fred Edwards • Hugh B. Ferguson III • David P. Fiori • Kellen A. Fleming • Robert William “Bob” Fogle III • Jonathan E. III • David P. Fiori • Kellen A. Fleming • Robert William “Bob” Fogle III • Jonathan E. French • Donovan Artie Garcia Jr. • Michael Dale “Mikey” Garrett • Charles Edward French • Donovan Artie Garcia Jr. • Michael Dale “Mikey” Garrett • Charles Edward Goff • Matthew Goodnature • Daniel David Groover • John Derek Gupton • Ramon Goff • Matthew Goodnature • Daniel David Groover • John Derek Gupton • Ramon Edward “Ray” Hain • Homer W. -

Reaching for the Stars When You Participate in the 2007 Csecc You Become a Star!

Donor Resource Guide Reaching for the Stars when you participate in the 2007 csecc you become a star! california state employees charitable campaign www.csecc.org “Every contribution is a step toward making someone’s life a little bit brighter. You have the chance to become someone’s star when you join Maria and me during the 2007 California State Employees Charitable Campaign and donate to your favorite charity.” Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor of California 2007 California State Employees Charitable Campaign Chair Fifty Years California State Employees Charitable Campaign 1957 Chair’sChair’s MessageMessage Dear Fellow State Employees, I am excited and honored to be chairman of the 2007 California State Employees Charitable Campaign. We raised more than $7.7 million for thousands of fantastic charities last year, and all of our volunteers and donors did a wonderful job. This year, I’m looking forward to an even bigger total. California has always been a leader in generosity and compassion, and now is our chance to show our support for all the charities that need our help. By fi lling out a simple form, we can give to worthwhile causes that do great work in our communities and around the world. When I came to America many years ago, I was impressed with the kindness of the people here in California. This campaign has been a huge success since 1957, so please join me as we continue to celebrate our 50-year tradition of making a difference. Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor 2007 CSECC Chair 2 TableTable ofof ContentsContents United Way Organizations (PCFDs) ............. -

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. M A Y - 2 0 1 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................1 Purpose.................................................................................................................................2 Background & Collaboration...............................................................................................3 The Landscape .....................................................................................................................6 The Wildfire Problem ..........................................................................................................8 Fire History Map................................................................................................................10 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................11 Reducing Structural Ignitability.........................................................................................12 x Construction Methods............................................................................................13 x Education ...............................................................................................................15