Bulletin 63, May 2012 Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcement Release 2013

THE HENRY R. KRAVIS PRIZE IN LEADERSHIP FOR 2013 AWARDED TO JOHANN OLAV KOSS FOUR-TIME OLYMPIC GOLD MEDALIST-TURNED- NONPROFIT LEADER Olympic speed skater from Norway founded Right To Play, an organization that uses the transformative power of play to educate and empower children facing adversity. Claremont, Calif., March 6, 2013–– Claremont McKenna College (CMC) announced today that four-time Olympic gold medalist and nonprofit leader Johann Olav Koss has been awarded the eighth annual Henry R. Kravis Prize in Leadership. The Kravis Prize, which carries a $250,000 award designated to the recipient organization, recognizes extraordinary leadership in the nonprofit sector. Koss will be presented with The Kravis Prize at a ceremony on April 18 held on the CMC campus. Founded in 2000 by Koss, Right To Play is a global organization that uses the transformative power of play to educate and empower children facing adversity. Right To Play’s impact is focused on four areas: education, health, peace building, and community development. Right To Play reaches 1 million children in more than 20 countries through play programming that teaches them the skills to build better futures, while driving social change in their communities. The organization promotes the involvement of all children and youth by engaging with girls, persons with disabilities, children affected by HIV/AIDS, as well as former combatants and refugees. “We use play as a way to teach and empower children,” Koss says. “Play can help children overcome adversity and understand there are people who believe in them. We would like every child to understand and accept their own abilities, and to have hopes and dreams. -

2011 May Digest

May 2011 • CoSIDA digest – 2 COSIDA MAY DIGEST Marco Island Convention on the Horizon Table of Contents . CoSIDA Seeking Board of Directors Nominations .......................... 4 Supporting CoSIDA 2011 CoSIDA Convention Registration Information ........................ 6 > Convention Schedule and Featured Speakers .....................7, 9-14 • Allstate Sugar Bowl ................ 15 Jackie Joyner-Kersee to Receive Enberg Award ....................20-21 CoSIDA Award Winner Feature Stories • ASAP Sports ............................. 8 Hall of Fame - Mark Beckenbach ............................................ 25 • CBS College Sports ................. 4 Hall of Fame - Charles Bloom ................................................. 26 Hall of Fame/Warren Berg Award - Rich Herman .................... 27 • ESPN ....................................... 60 Hall of Fame - Paul Madison ................................................... 28 • Fiesta Bowl ............................. 15 Trailblazer Award - Debby Jennings ........................................ 29 25-Year Award - Brian DePasquale ......................................... 30 • Heisman Trophy ..................... 45 25-Year Award - Tom Kroeschell ............................................. 31 • Liberty Mutual ......................... 45 25-Year Award - Tom Nelson ................................................... 32 25-Year Award/Lifetime Achievement - Walt Riddle ................ 33 • Lowe’s Senior CLASS Award .. 5 Academic All-America Hall of Fame Inductees Announced.....34-37 -

January-February 2003 $ 4.95 Can Alison Sheppard Fastest Sprinter in the World

RUPPRATH AND SHEPPARD WIN WORLD CUP COLWIN ON BREATHING $ 4.95 USA NUMBER 273 www.swimnews.com JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 $ 4.95 CAN ALISON SHEPPARD FASTEST SPRINTER IN THE WORLD 400 IM WORLD RECORD FOR BRIAN JOHNS AT CIS MINTENKO BEATS FLY RECORD AT US OPEN ������������������������� ��������������� ���������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������ � �������������������������� � ����������������������� �������������������������� �������������������������� ����������������������� ������������������������� ����������������� �������������������� � ��������������������������� � ���������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������������� ������������ ������� ���������������������������������������������������� ���������������� � ������������������� � ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������� ����������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������� ������������������� SWIMNEWS / JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 3 Contents January-February 2003 N. J. Thierry, Editor & Publisher CONSECUTIVE NUMBER 273 VOLUME 30, NUMBER 1 Marco Chiesa, Business Manager FEATURES Karin Helmstaedt, International Editor Russ Ewald, USA Editor 6 Australian SC Championships Paul Quinlan, Australian Editor Petria Thomas -

By Omission and Commission : 'Race'

National Library Bibliothbque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) KIA ON4 KIA ON4 Your hie Votre ri2ference Our Me Notre reference The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irriivocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant a la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prGter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes interessees. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial these. Ni la these ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent &re imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation. ISBN 0-315-91241-3 BY OMISSION AND COMMISSION: 'RACE' AND REPRESENTATION IN CANADIAN TELEVISION NEWS by Yasmin Jiwani B.A., University of British Columbia, 1979 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1984 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Communication @ Yasmin Jiwani 1993 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July, 1993 All rights reserved. -

Uefa Euro 2020 Final Tournament Draw Press Kit

UEFA EURO 2020 FINAL TOURNAMENT DRAW PRESS KIT Romexpo, Bucharest, Romania Saturday 30 November 2019 | 19:00 local (18:00 CET) #EURO2020 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit 1 CONTENTS HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK ................................................ 3 - 9 HOW TO FOLLOW THE DRAW ................................................ 10 EURO 2020 AMBASSADORS .................................................. 11 - 17 EURO 2020 CITIES AND VENUES .......................................... 18 - 26 MATCH SCHEDULE ................................................................. 27 TEAM PROFILES ..................................................................... 28 - 107 POT 1 POT 2 POT 3 POT 4 BELGIUM FRANCE PORTUGAL WALES ITALY POLAND TURKEY FINLAND ENGLAND SWITZERLAND DENMARK GERMANY CROATIA AUSTRIA SPAIN NETHERLANDS SWEDEN UKRAINE RUSSIA CZECH REPUBLIC EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS 2018-20 - PLAY-OFFS ................... 108 EURO 2020 QUALIFYING RESULTS ....................................... 109 - 128 UEFA EURO 2016 RESULTS ................................................... 129 - 135 ALL UEFA EURO FINALS ........................................................ 136 - 142 2 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK How will the draw work? The draw will involve the two-top finishers in the ten qualifying groups (completed in November) and the eventual four play-off winners (decided in March 2020, and identified as play-off winners 1 to 4 for the purposes of the draw). The draw will spilt the 24 qualifiers -

Guide Média 2 Table of Content Tables Des Matières

MEDIA GUIDE | GUIDE MÉDIA 2 Table of Content Tables des matières About Swimming Canada ............................................................................................................p.4 À propos de Natation Canada About the Canadian Olympic & Paralympic Swimming Trials presented by RBC.......................p.6 Au sujet des essais olympiques et paralympiques canadiens de natation présentés par RBC The Fast Facts about Para-swimming at the 2012 Paralympic Trials.........................................p.10 En bref au sujet de la paranatation aux essais paralympiques 2012 Biographies Men/Hommes Women/Femmes Isaac Bouckley p.12 Camille Berube p.34 Devin Gotell p.14 Morgan Bird p.36 Michael Heath p.16 Valerie Grand-Maison p.38 Brian Hill p.18 Brianna Jennett-McNeill p.40 Benoit Huot p.20 Kirstie Kasko p.42 Danial Murphy p.22 Sarah Mailhot p.44 Scott Patterson p.24 Sarah Mehain p.46 Michael Qing p.26 Summer Mortimer p.48 Brianna Nelson p.50 Adam Rahier p.28 Maxime Olivier p.52 Nathan Stein p.30 Aurelie Rivard p.54 Donovan Tildesley p.32 Katarina Roxon p.56 Rhea Schmidt p.58 Amber Thomas p.60 National Records Records nationaux p.62 Event Schedule Horaire de la compétition p.70 Media Contact: Martin RICHARD, Director of Communications, mrichard@swimming,ca, mob. 613 725.4339 3 About Swimming Canada Swimming Canada serves as the national governing body of competitive swimming. Competitive Canadian swimming has a strong heritage of international success includ- ing World and Olympic champions Cheryl Gibson, Victor Davis, Anne Ottenbrite, Alex Baumann, and Mark Tewksbury, among many others. Swimming Canada is proud to be a leading sport federation for the integration of athletes with a disability with its National Team and competitive programs. -

![Ioidiiy;]3Exui:]EA/CD]& /IM ) TÜ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1410/ioidiiy-3exui-ea-cd-im-t%C3%BC-291410.webp)

Ioidiiy;]3Exui:]EA/CD]& /IM ) TÜ

]%ioiDiiy;]3exui:]EA/CD]& /IM ) TÜ/()KK]]N(j AdEAdOItlT A Woïking Memory Analysis of the Dual Attention Component of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Ph.D. Dissertation Louise MaxSeld l^sydiologorlDeqpartment Lakehead University TThrmckarlSag^ ()}4,C%mad& Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. National Library BhUothèque nationale of Canada du Canada /boquwBtkxns and Aoquialtionaet BibWograpNc Services services bibliographiques 395W#*mglon8(rW 385.m*WeBngbn OUmmON K1A0N4 OUawaON K1A0N4 Canada Canada your#» The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de rqxroduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this diesis in microfbrm, vendre des copies de cette dièse sous paper or electronic formats. la 6xrme de microhche/füm, de reproduction sur p ^ier ou sur Amnat électronique. The author retains ownership of die L'auteur conserve la prxqaiété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels m ^ be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être inquimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. 0-612-85018-8 CanadS Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. W. T. Melnyk for his conEdence in me, and his support and encouragement; and Dr. H. G. Hayman and Dr. J. Jamieson for their guidance and direction. -

Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 Vs

CUSE.COM Christmas’ Season and Career Highs Points Season: 35 vs. Wake Forest Career: 35 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 FG Made S Y R A C U E Season: 13 vs. Wake Forest Career: 13 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 25 FG Attempted Season: 21 vs. Wake Forest Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 O R A N G E Senior 6-9 250 3-Point FGM Philadelphia, Pa. Season: 0 Career: 0 Academy of the New Church 3-Point FGA Season: 1 at North Carolina NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM Career: 1 at North Carolina, 2014-15 FT Made Ranks third in the ACC in scoring (17.5 ppg.), fourth in rebounding (9.1), fi fth in fi eld goal Season: 11 vs. Louisville percentage (.552), second in blocked shots (2.52), sixth in off ensive rebounds (3.13) and Career: 11 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 FT Attempted fi fth defensive rebounds (5.97). Season: 13 vs. Louisville Nominated for the 2015 Allstate NABC and WBCA Good Works Teams. Career: 13 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 Finalist for the Wooden Award. Rebounds Season: 16 vs. Hampton Finalist for the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award. Career: 16 vs. Hampton, 2014-15 Finalist for the Robertson Trophy. Off. Rebounds Named to Lute Olson Award Watch List. Season: 6 vs. Kennesaw State, Hampton, St. John’s, Long Beach State, at Duke Named to Naismith Award Midseason Top 30. Career: 8 vs. Boston College, 2013-14 Earned ACSMA Most Improved Player Award and was named to ACSMA All-ACC First Team Def. -

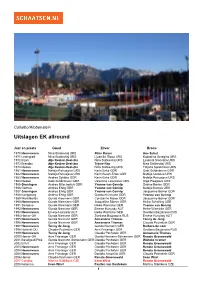

Collalbo/Klobenstein Uitslagen EK Allround

Collalbo/Klobenstein Uitslagen EK allround Jaar en plaats Goud Zilver Brons 1970 Heerenveen Nina Statkevitsj URS Stien Kaiser Ans Schut 1971 Leningrad Nina Statkevitsj URS Ljudmila Titova URS Kapitolina Seregina URS 1972 Inzell Atje Keulen-Deelstra Nina Statkevitsj URS Ljudmila Savrulina URS 1973 Brandbu Atje Keulen-Deelstra Trijnie Rep Nina Statkevitsj URS 1974 Medeo Atje Keulen-Deelstra Nina Statkevitsj URS Tatjana Sjelekhova URS 1981 Heerenveen Natalja Petrusjova URS Karin Enke GDR Gabi Schönbrunn GDR 1982 Heerenveen Natalja Petrusjova URS Karin Busch-Enke GDR Natalja Glebova URS 1983 Heerenveen Andrea Schöne GDR Karin Enke GDR Natalja Petrusjova URS 1984 Medeo Gabi Schönbrunn GDR Valentina Lalenkova URS Olga Plesjkova URS 1985 Groningen Andrea Mitscherlich GDR Yvonne van Gennip Sabine Brehm GDR 1986 Geithus Andrea Ehrig GDR Yvonne van Gennip Natalja Kurova URS 1987 Groningen Andrea Ehrig GDR Yvonne van Gennip Jacqueline Börner GDR 1988 Kongsberg Andrea Ehrig GDR Gunda Kleemann GDR Yvonne van Gennip 1989 West-Berlijn Gunda Kleemann GDR Constanze Moser GDR Jacqueline Börner GDR 1990 Heerenveen Gunda Kleemann GDR Jacqueline Börner GDR Heike Schalling GDR 1991 Sarajevo Gunda Kleemann GER Heike Warnicke GER Yvonne van Gennip 1992 Heerenveen Gunda Niemann GER Emese Hunyady AUT Heike Warnicke GER 1993 Heerenveen Emese Hunyady AUT Heike Warnicke GER Svetlana Bazjanova RUS 1994 Hamar-OH Gunda Niemann GER Svetlana Bazjanova RUS Emese Hunyady AUT 1995 Heerenveen Gunda Niemann GER Annamarie Thomas Tonny de Jong 1996 Heerenveen Gunda Niemann GER -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Suspect Arrested, Charged in Off- Campus Assault

[Where You Read It First Wednesday, March 10,1999 Volume XXXVIII, Number 31 , Suspect arrested, charged in off campus assault by DANIEL BARBARISI . the suspect was unavailable at the Daily Editorial Board . time. The officers left word ofthe A suspect has been identified, situation with family members and arrested, and charged in connec- advised the family to tell the sus tion with the hatred-fueled as- pect to tum himself in. Later that sault on a homosexual student on night, Rafferty surrendered him Feb. 28. Dean Rafferty, 22, ofAr- selfto the police after waiving his lington, was arrested this past. Miranda rights and making astate weekend on several counts of ment. assault and battery with a dan- Rafferty was arraigned at a 10 gerous weapon, his shorn foot. cal court on Monday, where he Rafferty was also charged with pleaded not guilty to the charges. anotherfelony violation stemming He was released on cash bail. A from the fact that his crime was trial date has not yet been set. hate-related. Explaining Rafferty'srelease on According to Tufts University bail, Lonero said, "We don't feel Police Department (TUPD) Lieu- that he's a danger to the Tufts tenant Charles Lonero, a rapid in- community.lfhecontacts anyone vestigation, and especially the involved in the case, he can be questioning ofindividuals present charged with intimidating a wit- ness, and I'll arrest him right then and there." Wonten's studies Lonero commented that he had never seen the cam pus as unified behind one ntajor approved by particular issue as they were in helping this inves tigation reach its conclu TeD Senate, faculty sion. -

2010-11 Syracuse Basketball Syracuse Individual

SYRACUSE INDIVIDUAL RECORDS 2010-11 SYRACUSE BASKETBALL Game Points Scored Field Goal Pct. (min 12 att.) 47 Bill Smith vs. Lafayette 1.000 Rick Dean (13-13) vs. Colgate 1/14/1971 2/14/1966 46 Dave Bing vs. Vanderbilt 1.000 Hakim Warrick (11-11) at 12/28/1965 Miami 2/14/2004 45 Dave Bing vs. Colgate 1.000 Arinze Onuaku (9-9) vs. 2/16/1965 E. Tenn. St. 12/15/2007 43 Gerry McNamara vs. BYU Free Throws Made (NCAA) 3/18/2004 18 Hakim Warrick vs. 43 Dave Bing vs. Buffalo Rhode Island 12/4/1965 11/30/2003 Points Scored, One Half 18 Allen Griffin at St. John’s 31 Adrian Autry (2nd) vs. Missouri 3/4/2001 (NCAA) 3/24/1994 16 Jonny Flynn vs. Connecticut 28 Gerry McNamara (1st) vs. BYU (BET) (6 OT) 3/12/2005 (NCAA) 3/18/2004 15 Hakim Warrick at Connecticut 28 Gerry McNamara (2nd) vs. 3/5/2005 Charlotte 11/26/2003 15 Hakim Warrick at St.John’s 27 Bill Smith (1st) vs. Lafayette 2/23/2005 1/14/1971 15 Derrick Coleman vs. Villanova 26 Demetris Nicholas (2nd) vs. 1/6/1990 St.Johns 1/2/2008 Free Throw Attempts Brandon Triche was a perfect six-for-six on three-point att empts Points Scored, Freshman in a Syracuse victory against Oakland on Dec. 22, 2009. 33 Carmelo Anthony vs. Texas 22 Hakim Warrick at Connecticut (NCAA) 4/5/2003 3/5/2005 30 Dwayne Washington vs. 22 Hakim Warrick vs. 3-pt. Field Goal Pct.