The Nesting of the Pacific Gull by HAROLD E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

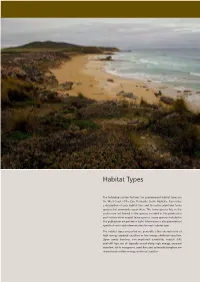

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Foraging Ecology of Great Black-Backed and Herring Gulls on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy by Rolanda J Steenweg Submitted In

Foraging Ecology of Great Black-backed and Herring Gulls on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy By Rolanda J Steenweg Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honours Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science at: Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2010 Supervisors: Dr. Robert Ronconi Dr. Marty Leonard ENVS 4902 Professor: Dr. Daniel Rainham TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 7 2.1 General biology and reproduction 7 2.2 Composition of adult and chick gull diets - changes over the breeding season8 2.3 General similarities and differences between gull species 9 2.4Predation on Common Eider Ducklings 10 2.5Techniques 10 3. MATERIALS AND METHODS 13 3.1 Study site and species 13 3.2 Lab Methods 16 3.3 Data Analysis 17 4. RESULTS 18 4.1 Pellet and regurgitate samples 19 4.2 Stable isotope analysis 21 4.3 Estimates of diet 25 5. DISCUSSION 26 5.1 Main components of diet 26 5.2 Differences between species and age classes 28 5.3 Variability between breeding stages 30 5.4 Seasonal trends in diet 32 5.5 Discrepancy between plasma and red blood cell stable isotope signatures 32 6. CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 33 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 35 REFERENCES 36 2 ABSTRACT I studied the foraging ecology of the generalist predators Great Black-backed (Larusmarinus) and Herring (Larusargentatus) Gulls on Kent Island, in the Bay of Fundy. To study diet, I collected pellets casted in and around nests supplemented with tissue samples (red blood cells, plasma, head feathers and primary feathers) obtained from chicks and adults for stable isotope analysis. -

Lesser Black-Backed Gull in NT 11 Lesser Black

March ] van Tets: Lesser Black-backed Gull in N .T. 11 1977 Lesser Black-backed instead of Dominican Gull at Melville Bay, N.T. In the Australian Bird Watcher 6 ( 5): 162-164, Plates 29- 31, and 6 (7) : 238, Con Boeke! (1976) reports seeing and photographing on October 27, 1974, at Melville Bay, N.T., two adult Black-backed Gulls. In comparison with the Pacific Gull Larus pacificus, and on the basis of a white tail without a black bar, he and his wife identified the birds as Dominican Gulls L. dominicanus, a species not previously recorded along the north coast of Australia. The photographs indicate only a single prominent white sub terminal mirror on the wing tip. This is a diagnostic characteristic of the Scandinavian and nominate form of the Lesser Black backed Gull L. f. fuscus. The Greater Black-backed Gull L. marinus, and the Dominican Gull have additional white mirrors on the wing tip. Other species of gull with a black rather than a dark grey mantle, have a white tail with a black bar as in the Pacific Gull. P. J. Fullagar, J. L. McKean and I found that colour copies of the photographs taken at Melville Bay depict a Scan dinavian Black-backed Gull and not a Dominican Gull, on com parison with series of photographs of both species. The Scan dinavian Lesser Black-backed Gull is known to migrate as far south as South Africa, and is therefore not an unlikely bird to reach Australia, where it has not been previously recorded. In October adult Dominican Gulls should be at their breeding colonies, while Lesser Black-backed Gulls would then be migrat ing southwards. -

REVIEWS Edited by J

REVIEWS Edited by J. M. Penhallurick BOOKS A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Britain and the World by is consistent in the text (pp 264 - 5) but uses Fleshy-footed Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1978. London: Collins. (a bette~name) in the map (p. 270). Pp xxviii + 292, b. & w. ills.?. 56-, col. pll2 +48, maps 314. 130 x 200 mm. B.25. Parslow does not use scientific names and his English A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Australia and the World by names follow the British custom of dropping the locally Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1980. London: Collins. superfluous adjectives, Thus his names are Leach's Storm- Pp xxviii + 276, b. & w. ills c. 56, col. pll2 + 48, maps 300. Petrel, with a hyphen, and Storm Petrel, without a hyphen; 130 x 200 mm. $A 19.95. and then the Fulmar, the Gannet, the Cormorant, the Shag, A Guide to Seabirds on the Ocean Routes by Gerald Tuck, the Kittiwake and the Puffin. On page 44 we find also 1980. London: Collins. Pp 144, b. & w. ills 58, maps 2. Storm Petrel but elsewhere Hydrobates pelagicus is called 130 x 200 mm. Approx. fi.50. the British Storm-Petrel. A fourth variation in names occurs on page xxv for Comparison of the first two of these books reveals a ridi- seabirds on the danger list of the Red Data Book, where culous discrepancy in price, which is about the only impor- Macgillivray's Petrel is a Pterodroma but on page 44 it is tant difference between them. -

Are Kelp Gulls Larus Dominicanus Replacing Pacific Gulls L. Pacificus

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 47–55 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36047055 Are Kelp Gulls Larus dominicanus replacing Pacific Gulls L. pacificus in Tasmania? William C. Wakefield1, 2, Els Wakefield2 and David A. Ratkowsky3* 1Deceased 212 Alt-na-Craig Avenue, Mount Stuart TAS 7000, Australia 3Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 98, Hobart TAS 7001, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The nominate subspecies of the Pacific Gull Larus pacificus, widespread along the coast of southern Australia, may be under threat from the slightly smaller, but opportunistically competitive, self-introduced Kelp Gull L. dominicanus. To assess this threat to the Pacific Gull in Tasmania, we documented colony size of large gulls across many Tasmanian islands over a period of 24 breeding seasons (1985–2009). The most northerly Kelp Gull nests on the Tasmanian mainland were located at Paddys Island, St Helens. There were no reports of Kelp Gulls along any part of the northern coast of Tasmania abutting Bass Strait, although there were sporadic sightings on islands of the Furneaux Group. The stronghold of the Kelp Gull in Tasmania is the Estuary of the Derwent River and its surrounding bays and channels, where this species is present in much larger numbers than the Pacific Gull, but nevertheless co-exists with that species. We found no evidence for dramatic changes in numbers since 1985. All Pacific Gull nests were on small islands, and there were none at Orielton Lagoon, which became the third biggest Kelp Gull colony studied in the south-east of Tasmania. -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Movements of Michigan Herring Gulls*

BIRD-BANDING A JOURNXL OF ORNITHOLOGICALINYESTIGATION Vol. XXX April, 1959 No. 2 MOVEMENTS OF MICHIGAN HERRING GULLS* BY W. JoHN SMITH INTRODUCTION Since July 1931 Mr. Claud C. Ludwig of 279 Durand Street, East Lansing,Michigan, and his two sons,Dr. FrederickE. and Dr. Claud A. (and sometimesa small crew of helpers), have banded a total of 37,414 juvenile Herring Gulls, Larus argentatus,in 17 Michigan colonies.Mr. Ludwig recentlyhas made his carefully kept recordsof this work availableto Dr. GeorgeJ. Wallace of the Departmentof Zoology,Michigan State University, for analysisby a student. This report is that analysis. Sincerethanks are due to Mr. Ludwig for supplyingthese data, and for his patienthelp in answeringmy queries aboutthe field work in which I had no part. The nearly 105,000 birds of many speciesbanded by the Ludwigteam standas a truly remark- able tribute to the servicethese men have done ornithology. To Dr. Wallace I should also like to expressmy gratitudefor his constant advice,suggestions, and carefulcriticism during both the analysisand literature-searchthat precededthe writing of this report and the period of writing itself. Dr. P. J. Clark, alsoof the Departmentof Zoology, has instructedme on the use of the contingencychi-square method and helpedin its applicationto the data. The banded gulls have to date yielded some 1,143 recoveries,not includingthose young birds recoveredon or within a few milesof the coloniesshortly after being banded. The high mortality of juvenile HerringGulls still in the colonyis too well knownto requirediscussion here; and the inclusion of such recoverieswould obviously tell us nothingnew concerningthe species'life history,but rather would serveonly to distortour pictureof its movements.These 1,143 recov- eries,representing 3.06% of the birds banded,provide a large sample from which has emergeda clear picture of the seasonaldistribution of Michigan-bornHerring Gulls. -

The Significance of Rubbish Tips As an Additional Food Source for the Kelp Gull and the Pacific Gull in Tasmania

The Significance of Rubbish Tips as an Additional Food Source for the Kelp Gull and the Pacific Gull in Tasmania by e. e--~'" (& G. M. Coulson, B.A. (Hans.), Dip.Ed. (Melb.) and .J~ R.I. Coulson, B .Sc., Dip.Ed. (Melb.) Being a thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies Centre for Environmental Studies University of Tasmania August, 1982 nl\, (l,_ '/ Cl-- \'\~'.2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to our supervisors, Dr. A.M.M. Richardson and Dr. J.J. Todd, and our external advisors, Mr. A.W.J. Fletcher and Mr. J.G.K. Harris, for their guidance in the preparation and planning of this thesis. Mrs. L. Ramsay typed the thesis. Mr. D. Barker (Tasmanian Museum, Hobart) and Mr. R.H. Green (Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston) gave us access to their gull collections. Mr. G. Davis assisted with the identification of chitons. Officers of the Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service provided information, assistance, equipment and specimens, and officers of the Tasmanian Department of the Environment gave us information on tips. The cities and municipalities in south-east Tasmania granted permission to study gulls at tips under their control, and we are particularly grateful for the co-operation shown by council staff at Clarence, Hobart and Kingborough tips. Mr. R. Clark allowed us to observe gulls at Richardson's Meat Works, Lutana. CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 1. INTRODUcriON 3 2. GULL POPULATIONS IN THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE 7 2.1 Population Increases 8 2.1.1 Population size and rates·of change 10 2.1.2 Growth of breeding colonies 13 2.2 Reasons for the Population Increase 18 2.2.1 Protection 18 2.2.2 Greater food availability 19 2.3 Effects of Population Increase 22 2.3.1 Competition with other species 22 2.3.2 Agricultural pests 23 2.3.3 Public health risks 24 2.3.4 Urban nesting 25 2.3.5 Aircraft bird-strikes 25 2.4 Future Trends 26 3. -

Laridaerefspart2 V1.2.Pdf

Introduction This is the second of two gull reference lists. It includes all those species of Gull that are included in the genus Larus. I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2014 & 2015 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Chris Batty and Graham Prole for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Index With some differences with the larger white-headed gulls, the general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2014. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 4.3 accessed September 2014]). Joe Hobbs Cover Main image: American Herring Gull. Dingle Harbour, Co. Kerry, Ireland. 8th April 2004. Picture by Chris Batty. Vignette: Lesser Black-backed Gull. Sean Walsh Park, Tallaght, Co. Dublin, Ireland. 14th July 2012. Picture by Graham Prole. Version Version 1.2 (September 2014). Species Page No. American Herring Gull [Larus smithsonianus] 34 Armenian Gull [Larus armenicus] 44 Belcher's Gull [Larus belcheri] 6 Black-tailed Gull [Larus crassirostris] 7 California Gull [Larus californicus] 15 Caspian Gull [Larus cachinnans] 38 Common Gull [Larus canus] 9 Glaucous Gull [Larus hyperboreus] 24 Glaucous-winged Gull [Larus glaucescens] 20 Great Black-backed Gull [Larus marinus] 16 Heermann's Gull [Larus heermanni] 8 Herring Gull [Larus argentatus] 30 Heuglin's Gull [Larus heuglini] 52 Iceland Gull [Larus glaucoides] 26 Kelp Gull [Larus dominicanus] 17 Lesser Black-backed Gull [Larus fuscus] 47 Olrog's Gull [Larus atlanticus] 6 Pacific Gull [Larus pacificus] 6 Ring-billed Gull [Larus delawarensis] 13 1 Short-billed Gull [Larus brachyrhynchus] 12 Slaty-backed Gull [Larus schistisagus] 45 Thayer's Gull [Larus thayeri] 28 Vega Gull [Larus vegae] 37 Western Gull [Larus occidentalis] 22 Yellow-footed Gull [Larus livens] 23 Yellow-legged Gull [Larus michahellis] 40 2 Relevant Publications Bahr, N. -

News and Notes — W Eb E Xtra

NEWS AND NOTES — W EB E XTRA The following genera were proposed in 2005 by J.-M. Pons, A. Hassanin, and P.-A. Crochet in a taxonomic revision of the gull family: “Phylogenetic relationships within the Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves ) inferred from mitochondrial markers” (Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37:686–699). Larus (“white-headed” group) Gray-hooded Gull C. cirrocephalus Heermann’s Gull L. heermanni Hartlaub’s Gull C. hartlaubii Mew Gull L. canus Ring-billed Gull L. delawarensis Ichthyaetus (“black-headed” group) California Gull L. californicus Relict Gull I. relictus Herring Gull L. argentatus Audouin’s Gull I. audouinii American Herring Gull L. smithsonianus Mediterranean Gull I. melanocephalus Yellow-legged Gull L. michahellis Great Black-headed Gull I. ichthyaetus Caspian Gull L. cachinnans Sooty Gull I. hemprichii Armenian Gull L. armenicus White-eyed Gull I. leucophthalmus Thayer’s Gull L. thayeri Iceland Gull L. glaucoides Leucophaeus (“hooded” group) Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus Laughing Gull L. atricilla Slaty-backed Gull L. schistisagus Franklin’s Gull L. pipixcan Yellow-footed Gull L. livens Lava Gull L. fuliginosus Western Gull L. occidentalis Gray Gull L. modestus Glaucous-winged Gull L. glaucescens Dolphin Gull L. scoresbii Glaucous Gull L. hyperboreus Great Black-backed Gull L. marinus Hydrocoloeus Kelp Gull L. dominicanus Little Gull H. minutus Ross’s Gull H. roseus Larus (“band-tailed” group) Pacific Gull L. pacificus Saundersilarus Olrog’s Gull L. atlanticus Saunders’s Gull S. saundersi Belcher’s Gull L. belcheri Black-tailed Gull L. crassirostris Xema Sabine’s Gull X. sabini Chroicocephalus (“masked” group) Slender-billed Gull C. -

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E. Johnstone and J.C. Darnell Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia 6000 April 2020 ____________________________________ The area covered by this Western Australian Checklist includes the seas and islands of the adjacent continental shelf, including Ashmore Reef. Refer to a separate Checklist for Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Criterion for inclusion of a species or subspecies on the list is, in most cases, supported by tangible evidence i.e. a museum specimen, an archived or published photograph or detailed description, video tape or sound recording. Amendments to the previous Checklist have been carried out with reference to both global and regional publications/checklists. The prime reference material for global coverage has been the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) World Bird List, The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volume, 1 (Lynx Edicions, Barcelona), A Checklist of the Birds of Britain, 8th edition, the Checklist of North American Birds and, for regional coverage, Zoological Catalogue of Australia volume 37.2 (Columbidae to Coraciidae), The Directory of Australian Birds, Passerines and the Working List of Australian Birds (Birdlife Australia). The advent of molecular investigation into avian taxonomy has required, and still requires, extensive and ongoing revision at all levels – family, generic and specific. This revision to the ‘Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia’ is a collation of the most recent information/research emanating from such studies, together with the inclusion of newly recorded species. As a result of the constant stream of publication of new research in many scientific journals, delays of its incorporation into the prime sources listed above, together with the fact that these are upgraded/re-issued at differing intervals and that their authors may hold varying opinions, these prime references, do on occasion differ.