Democracy Under Threat in West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Monday, 21st of December, 2020 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 21-12-2020 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE SANJIB BANERJEE 16 On 21-12-2020 2 2 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE DB At 12:15 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SANJIB BANERJEE 16 On 21-12-2020 3 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE MOUSHUMI BHATTACHARYA DB At 03:30 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 21-12-2020 4 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 12:45 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 21-12-2020 5 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 21-12-2020 6 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 21-12-2020 7 20 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 12:55 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 21-12-2020 8 21 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE JOYMALYA BAGCHI 28 On 21-12-2020 9 24 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VI At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 5 On 21-12-2020 10 38 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - VII At 10:45 AM 5 On 21-12-2020 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 40 SB At 03:00 PM 25 On 21-12-2020 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 44 SB - I At 10:45 AM 4 On 21-12-2020 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 54 SB - II At 10:45 AM 6 On 21-12-2020 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 65 SB At 03:30 PM 38 On 21-12-2020 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE ASHIS KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 69 SB - IV At 10:45 AM 30 On 21-12-2020 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 73 SB - V At 10:45 AM 13 On 21-12-2020 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 77 SB - VI At 10:45 AM SL NO. -

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

Mamata Wants Change of Guv, Writes to PM, Prez

EasternChroniWINDOW TO THE EAST cle WEATHERWATCH THAI WORKERS KILLED in INDIAN DATA CENTRE sector INDIAN MEN AND WOMEN’S Max 37°c IsraelPalestinian conflict as needs $3.7 bn investment by cricket teams may travel Min 29°c truce calls mount P 6 2023 to meet demand P 9 together to UK P 10 Humidity 65 VOL II, ISSUE 224 PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY FROM SILCHAR GUWAHATI KOLKATA PAGES: 10 epaper at: www.easternchronicle.net PRICE `5 WEDNESDAY, MAY 19, 2021 Narada row: Arrested TMC Mamata wants change of leaders admitted to hospital Guv, writes to PM, Prez AGENCIES summer's assembly polls. Covid pandemic . Banerjee's letters despatched Trinamool Congress sources KOLKATA: State Chief Minister on Tuesday alleges that said the party was considering Mamata Banerjee has written Governor Dhankhar has been a resolution passed by the legis- to President and Prime Min- raking up an 'exaggerated ver- lative assembly demanding the ister demanding a change of sion' of violence in West Bengal removal of the Governor. Sovan Chatterjee, Subrata Mukherjee & Madan Mitra Governor in the interest of since the election. The Governor has been at dag- "good governance" in the state. It said the whole exercise is to gers drawn with the Trinamool AGENCIES apprehended by the central rectional home after completion The letter comes immediately project a ' highly inflated version government ever since he took agency in the case, was shifted of check-up as he did not wish to after the CBI arrested four ' of the law and order situation charge. KOLKATA: State minister Sub- to a health facility in Presidency get admitted there, an official of Trinamool leaders, including in West Bengal, overlooking the "He is trying to build up a rata Mukherjee, TMC MLA Correctional Home after he the medical facility said. -

4 Patrimonial and Programmatic Talking About Democracy in a South Indian Village

4 Patrimonial and Programmatic Talking about Democracy in a South Indian Village PAMELA PRICE AND DUSI SRINIVAS How do people in India participate politically, as citizens, clients and/or subjects?1 This query appears in various forms in ongoing debates concerning the extent and nature of civil society, the pitfalls of patronage democracy, and the role of illegal- ity in political practice, to name a few of the several concerns about political spheres in India. A focus for discussion has been the relationship of civil society institutions (with associated principles of equality and fairness) to political spheres driven mainly by political parties and to what Partha Chatterjee desig- nated as ‘political society’.2 Since 2005, with the publication of the monograph, Seeing the State: Governance and Governmentality in India (Corbridge et al.), there is growing support for the argument that political cultures and practices in India, from place to place and time to time, to greater and lesser degrees, include 1. Thanks to those who commented on earlier drafts of this piece when it was presented at the Department of Political Science at the University of Hyderabad, the South Asia Symposium in Oslo, and at the workshop ‘Practices and Experiences of Democracy in Post-colonial Locali- ties’, part of the conference, ‘Democracy as Idea and Practice’ organized by the University of Oslo. We are grateful to K.C. Suri for suggesting the term ‘programmatic’ in our discussions of the findings here. Thanks to the editors of this volume, David Gilmartin and Sten Widmalm for reading and commenting on this piece. -

(Autonomous) ANNUAL REPORT:2019–2020

RNLK Annual Report: 2019 – 20 Raja Narendra Lal Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) AANNNNUUAALL RREEPPOORRTT:: 22001199 –– 22002200 64th Foundation Day,2020 22nd August 2020 Page 1 RNLK Annual Report: 2019 – 20 The Report 1. Respected Chief Guest Dr. Swapna Ghorai, Principal of Ramananda College, Bishnupur and Alumna of our College; respected Special Guest Shri Tarapada Pal, ex-President of the Governing Body of our College; respected Dr. Rina Pal and Dr. Parthapratim Chakraborty, teachers’ representatives, GB, our beloved teachers, non-teaching staff members, hostel employees, students, friends and well-wishers. 2. On this 64thFoundation Day we heartily welcome all and extend our sincere thanks and gratefulness and warm wishes to the honoured guests and offer our best wishes to the teachers, non-teaching staff members, hostel employees, students, research scholars, research assistants, counsellors and other dignitaries. It is also our pleasure to welcome the media persons who have taken all the trouble to join us on this happy occasion. We observe this day to renew our ideas and determination for promoting the cause of education for our learners and society at large. Education is the best means of ensuring social justice, national integrity and communal harmony. 3. On the 63rdFoundation Day ceremony in 2019, we were privileged to have the honourable presence of respected Chief Guest Smt. Bhakti Bhoumik, an Alumna of Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College and former Teacher in Charge of Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya, Purba Medinipur; and Shri Ashotosh Das, ex-staff, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College, and other dignitaries from different walks of our society. -

Subject Name User Id Guardian's Name BENGALI AYANTIKA SOME VUDDE2010076 ALOKE KUMAR SOME BENGALI ZESMINA KHATUN VUDDE2010079

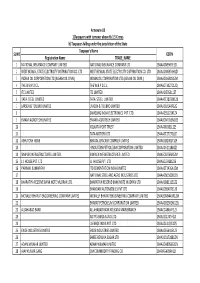

Directorate of Distance Education, Vidyasagar University Part - I 2020-2021 Student List Subject Name User Id Guardian's Name BENGALI AYANTIKA SOME VUDDE2010076 ALOKE KUMAR SOME BENGALI ZESMINA KHATUN VUDDE2010079 ATAUR RAHAMAN KHAN BENGALI MOU SHOW VUDDE2010081 GANESH SHOW BENGALI DEBJANI CHAKRABORTY VUDDE2010162 GOUR CHAKRABORTY BENGALI SOURAV GHOSH VUDDE2010165 SUSANTA GHOSH BENGALI TAPAS KUNDU VUDDE2010186 SUKUMAR SUNDAR KUNDU BENGALI FALGUNI SAMANTA VUDDE2010191 PRIMAL SAMANTA BENGALI RIMPA CHATTERJEE VUDDE2010310 TIMIR CHATTERJEE BENGALI JHUNU PRADHAN VUDDE2010360 ASHOKE KUMAR PRADHAN BENGALI SUTAPA CHATTERJEE VUDDE2010441 DEBDAS CHATTERJEE BENGALI PARI MAHATO VUDDE2010450 SUSEN MAHATO BENGALI ARITI ADHIKARY VUDDE2010472 ARUN KUMAR ADHIKARY BENGALI SUSMITA DULEY VUDDE2010489 NIMAI KUMAR DULEY BENGALI SANJOY MONDAL VUDDE2010498 PRAHLAD MONDAL BENGALI SAMARESH SAHOO VUDDE2010659 SANAT SAHOO BENGALI SUSMITA DAS VUDDE2010661 SHANTIPADA DAS BENGALI PALLABI BHOWMICK VUDDE2010700 SUNIL BHOWMICK BENGALI RUPASHREE MAJI VUDDE2010758 AJIT KUMAR MAJI BENGALI SUVADIP DASH VUDDE2010815 DEBASISH DASH BENGALI PRIYANKA DE VUDDE2010846 BALARAM DE BENGALI ANANYA PATTANAYAK VUDDE2010911 ASOK PATTANAYAK BENGALI TUSI BHOWMIK VUDDE2010917 TAPAS BHOWMIK BENGALI JUI NASKAR VUDDE2010931 DEBESH NASKAR BENGALI PRALAY PAIN VUDDE2010960 TAPAN KUMAR PAIN BENGALI KOUSHIK SANTRA VUDDE2010962 TAPAS SANTRA BENGALI MEDHA BHATTACHARYA VUDDE2010965 DEBASISH BHATTACHARYA BENGALI SWARUPA DAS VUDDE2011048 KOLLOL KUMAR DAS BENGALI SOUMIKA DHARA VUDDE2011062 SUBRATA KUMAR -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

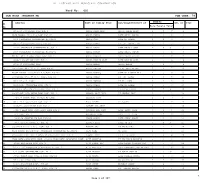

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Congress in the Politics of West Bengal: from Dominance to Marginality (1947-1977)

CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL For the award of Doctor of Philosophy In History By Babulal Bala Assistant Professor Department of History Raiganj University Raiganj, Uttar Dinajpur, 733134 West Bengal Under the Supervision of Dr. Ichhimuddin Sarkar Former Professor Department of History University of North Bengal November, 2017 1 2 3 4 CONTENTS Page No. Abstract i-vi Preface vii Acknowledgement viii-x Abbreviations xi-xiii Introduction 1-6 Chapter- I The Partition Colossus and the Politics of Bengal 7-53 Chapter-II Tasks and Goals of the Indian National Congress in West Bengal after Independence (1947-1948) 54- 87 Chapter- III State Entrepreneurship and the Congress Party in the Era of Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy – Ideology verses Necessity and Reconstruction 88-153 Chapter-IV Dominance with a Difference: Strains and Challenges (1962-1967) 154-230 Chapter- V Period of Marginalization (1967-1971): 231-339 a. Non-Congress Coalition Government b. Presidential Rule Chapter- VI Progressive Democratic Alliance (PDA) Government – Promises and Performances (1972-1977) 340-393 Conclusion 394-395 Bibliography 396-406 Appendices 407-426 Index 427-432 5 CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) ABSTRACT Fact remains that the Indian national movement found its full-flagged expression in the activities and programmes of the Indian National Congress. But Factionalism, rival groupism sought to acquire control over the Congress time to time and naturally there were confusion centering a vital question regarding ‘to be or not to be’. -

Tnpsc Bits National

• • May – 20 TNPSC BITS ❖ The Indian Council of Medical Research recently dropped the plasma therapy from COVID-19 treatment. o The decision was taken as the procedure was found to be ineffective. ❖ Every year, the World AIDS Vaccine Day / HIV Vaccine Awareness Day is celebrated on May 18. o This year the day is celebrated under the theme is 'Global Solidarity'. NATIONAL Narada Bribery Case ❖ The Central Bureau of Investigation arrested the TMC Ministers of West Bengal, Subrata Mukherjee, Firhad Hakim, MLA Madan Mitra and Sovan Chattopadhyay (former Kolkata Mayor). ❖ In Narada Bribery Case, the state ministers were shown taking money in a video footage. ❖ Calcutta High Court had ordered a CBI probe against the sting operation in Narada Bribery case in March 2017 ❖ CBI can investigate a crime in the state after the consent from the State Government. ❖ However, the Supreme Court or the High court shall order CBI to conduct investigation anywhere in the country. Norms on imports of pulses ❖ The Government of India recently allowed free import of tur, moong and urad dal. ❖ All the three pulses have been put under non-restricted list. ❖ This is because their retail prices increased in the last few weeks due to low stock levels with the traders. ❖ Also, the Government of India has announced that the import consignments should be cleared strictly before November 30, 2021. ❖ India primarily imports these three pulses from Myanmar and African countries. • • Jal Jeevan Mission - first instalment ❖ The Union Government released Rs 5,968 crores of rupees to implement the Jal Jeevan Mission. ❖ The funds were released to fifteen states. -

Public Service Commission, West Bengal 161A, S.P

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161A, S.P. Mukherjee Road, Kolkata – 700 026 IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT Half-Yearly Departmental Examination of Officers of the Government of West Bengal (including A.I.S Officers), May, 2018. The above examination will be held in the Examination Halls of the Commission on and from the 12th June, 2018. The detailed programme of examination, proforma of Letter of Identification and the lists of officers to be admitted in the said examination will be available in the Commission’s website at www.pscwbonline.gov.in . The concerned Departments/Directorates are requested to issue Letter of Identification of those eligible officers which have only forwarded by them through proper channel after making sure that previous records in respect of them have been checked meticulously. Utmost care should be taken to ensure that no Letter of Identification is issued in favour of any debarred candidate. In no case debarred candidates will be allowed to sit for the said examination. No Letter of Identification will be issued to the eligible officers from the office of the Commission. Identity Card along with the Letter of Identification will have to be produced by the candidates at the examination center. BAG AND BAGAGE, WATER BOTTLE, MOBILE PHONE OR ANY OTHER TYPE OF ELECTRONIC GADGET OF COMMUNICATION IN THE CAMPUS OF THE EXAMINATION HALL IS STRICTLY BANNED. INFRINGEMENT OF THIS INSTRUCTION WILL ATTRACT PENAL ACTION INCLUDING BAN FROM FUTURE EXAMINATIONS. Half Yearly Depttl. / L.D./S.I./R.L./E.B./Professional Examination, May/November, 20 . LETTER OF IDENTIFICATION (TO BE PRODUCED AT THE EXAMINATION HALL) This is to certify that Shri / Smt. -

Cheap Filter to Solve Arsenic Crisis - Times of India

30/07/2020 Cheap filter to solve arsenic crisis - Times of India Printed from Cheap filter to solve arsenic crisis TNN | Sep 12, 2012, 04.04 AM IST KOLKATA: The solution to Jadavpur's arsenic problem may lie in the constituency itself, but the civic bosses are unaware of it. Drinking water has been a long-standing problem in the constituency. In last year's assembly polls, the high-decibel contest between then chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee and former chief secretary Manish Gupta centred around it, or rather, the lack of it. Gupta had promised to address the issue that had left the former CM's constituency parched. A year and a half later, Gupta, who is now power minister, hasn't been able to fulfil the promise. Not that anyone can accuse him of lacking in effort. He did try to get the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) to sink tube wells in the area to meet the acute shortage during summer. But then the civic body ran into trouble as water from hand-pumps in the locality tested positive for arsenic. Though KMC contested the results cited by arsenic expert Dipankar Chakraborty, it later conceded that traces of arsenic were indeed present in drinking water drawn from tube wells in the region. "It is dangerous to consume drinking water unless it is made arsenic-free," said Chakraborty, director (research) at school of environment studies, Jadavpur University, cautioning against sinking of more tube wells in the arsenic-affected belt. Even as the civic body ponders over what to do till it is in a position to supply adequate water to densely populated localities along the belt, KMC remained ignorant of a solution that is within hand, but has remained untapped due to its disconnect with scientific and academic institutions. -

Ward No: 001 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 001 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 96/H/26 COSSIPORE ROAD KOL 2 ABDUL AZIM KHAN ABDUL HAKIM KHAN 2 5 7 1 2 RAJA BAGAN 26/5 K.C.ROAD KOL-02 ABDUL FAHIM LATE ABDUL RAHIM 3 3 6 2 3 26/1 KHAGENDRA CHATTERJEE RD,KOL-2 ABDUL GANI LATE MD ZAHIR 2 2 4 3 4 99/H/17 COSSIPORE ROAD, KOL-02 ABDUL HAMID LT. SK. AMINUDDIN 1 2 3 4 5 26/18 KHAGENDRA CHATTERJEE RD,KOL-2 ABDUL KADIR LATE BADRUL GANI 6 4 10+ 5 6 26/8 KHAGENDRA CHATTERJEE RD,KOL-2 ABDUL KARIM LATE ABDUL HAKIM 5 4 9 6 7 56 NO 96/H/7 COSSIPORE ROAD KOL-2 ABDUL KHALED LATE YASIN SHEIKH 3 4 7 7 8 96/H/7 COSSIPORE ROAD KOL 2 ABDUL KNALIK GAZI LATE MUSLIM GAZI 4 5 9 8 9 96/H/46 COSSIPORE ROAD ABDUL MAMUD ABDUL KABIB 5 2 7 9 10 COSSIPORE 96/H/32 C.P. ROAR KOL=2 ABDUL RAZZAK LT.MD.KARI MIYAN 3 4 7 10 11 BASAK BAGAN 22/1/H/22 K.C.ROAD KOL-02 ABDUL RAZZAQ LATE MD LIAKAT ALI 4 5 9 11 12 COSSIPORE 96/H/47 K.S. ROAD, KOL-02 ABDUL SAHID LT. SK. HANIF 2 4 6 12 13 96/H/13 C.P. ROAD ABDUL TABBAR LT.MD.