Second Circuit Review First Ammendment Law: Libel of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miscavige Legal Statements: a Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection

SPEAKING OUT ABOUT ORGANIZED SCIENTOLOGY ~ The Collected Works of L. H. Brennan ~ Volume 1 The Miscavige Legal Statements: A Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection Written by Larry Brennan [Edited & Compiled by Anonymous w/ <3] Originally posted on: Operation Clambake Message board WhyWeProtest.net Activism Forum The Ex-scientologist Forum 2006 - 2009 Page 1 of 76 Table of Contents Preface: The Real Power in Scientology - Miscavige's Lies ...................................................... 3 Introduction to Scientology COB Public Record Analysis....................................................... 12 David Miscavige’s Statement #1 .............................................................................................. 14 David Miscavige’s Statement #2 .............................................................................................. 16 David Miscavige’s Statement #3 .............................................................................................. 20 David Miscavige’s Statement #4 .............................................................................................. 21 David Miscavige’s Statement #5 .............................................................................................. 24 David Miscavige’s Statement #6 .............................................................................................. 27 David Miscavige’s Statement #7 .............................................................................................. 29 David Miscavige’s Statement #8 ............................................................................................. -

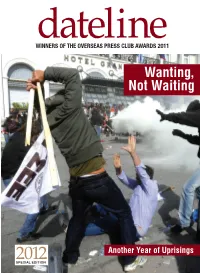

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK RICHARD BEHAR, Plaintiff, V. U.S. DEPARTMENT of HOMELAND

Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 1 of 53 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK RICHARD BEHAR, Plaintiff, Nos. 17 Civ. 8153 (LAK) v. 18 Civ. 7516 (LAK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, Defendant. PLAINTIFF’S MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF CROSS-MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE GOVERNMENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT John Langford, supervising attorney David Schulz, supervising attorney Charles Crain, supervising attorney Anna Windemuth, law student Jacob van Leer, law student MEDIA FREEDOM & INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC ABRAMS INSTITUTE Yale Law School P.O. Box 208215 New Haven, CT 06520 Tel: (203) 432-9387 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiff Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 2 of 53 STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT Plaintiff respectfully requests oral argument to address the public’s right of access under the Freedom of Information Act to the records at issue. Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 3 of 53 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 2 A. Secret Service Protection for Presidential Candidates ....................................................... -

ENT ~~~'~Orqx Eecop~.R ~ * ~ ~Z2~'

$ENT ~~~'~orQX eecop~.r ~ * ~ ~Z2~'aVED T~u~TcHcouN~ PF~OSECUT~NG A1T~ L_t\~R Z~ 1~99O eIICD 1 2 UNITED ST .~~d~~oURu1r PbP~ )A1~9O 3 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA ~ W UNITED STATES, Plaintiff, 6 v. ) No. cR-S60616-DL7 7 ) STEPHEN 71510 WI, ) MMORaNDUX OPIUZON 8 Defendant. 9 10 On camber 27, 1969, this Court heard the government's motion to exclude certain expert testimony proffered b~ 12 defendant. Assistant United States Attorney Robert Dondero IS appeared for the government. Hark Nuri3~ appeared for defendant. 14 Since the hearing the partiem have filed supplemental briefing, which the Court has received and reviewed. For all the following 16 reasons, the Court GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART the 17 government' a motion. 18 19 I * BACKGROUND FACTS 20 The United States indicted Steven ?iuhman on eleven counts 21 of mail fraud, in violation of IS U.S.C. 1 1341, 011 September 22 23, 1968. The indictment charges that Xr. Fishman defrauded 23 various federal district courts, including those in the Northern 24 District of California, by fraudulently obtaining settlement 25 monies and securities in connection with .hareholder class action 28 lawsuits. This fraud allegedly occurred over a lengthy period 27 of time -~ from September 1963 to Nay 1958. 28 <<< Page 1 >>> SENT ~y;~grox ~ ~ * Two months after his indictment, defendant notified this 2 Court of his intent to rely on an insanity defense, pursuant to Rule 12.2 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Within the context of his insanity defense, defendant seeks to present 5 evidence that influence techniques, or brainwashing, practiced 8 upon him by the Church of Scientology ("the Church") warn a cause of his state of mind at the tim. -

Shopping for Religion: the Change in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law, 51 Buff

Buffalo Law Review Volume 51 | Number 1 Article 4 1-1-2003 Shopping for Religion: The hC ange in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law Rebecca French University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Rebecca French, Shopping for Religion: The Change in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law, 51 Buff. L. Rev. 127 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol51/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo chooS l of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shopping for Religion: The Change in Everyday Religious Practice and its Importance to the Law REBECCA FRENCHt INTRODUCTION Americans in the new century are in the midst of a sea- change in the way religion is practiced and understood. Scholars in a variety of disciplines-history of religion, sociology and anthropology of religion, religious studies- who write on the current state of religion in the United States all agree on this point. Evidence of it is everywhere from bookstores to temples, televisions shows to "Whole Life Expo" T-shirts.1 The last thirty-five years have seen an exponential increase in American pluralism, and in the number and diversity of religions. -

Lonesome Squirrel

LONESOME SQUIRREL by STEVEN FISHMAN © 1991 Steven Fishman. Non-profit reproduction is encouraged. CONTENTS Chapter Title Page 01 Raw Meat Off The Street 4 02 Life is Just A Present Time Problem 25 03 Theta Doesn't Grow On Trees 36 04 If You Blink, You Flunk 85 05 In Guardians We Trust 95 06 A Case Of First Suppression 105 07 The Environment Is A Nice Place To Visit, 116 But I Wouldn't Want To Live Here 08 Does Anybody Have A Bridge They Can Sell Me? 127 09 Romancing LaVenda 138 10 A Valence In Every Port 171 11 Families Are Nothing But Trouble 183 12 Blank Scripts For Acting Classes 202 13 Breaking Up Is Hard To Do, But We Can Help 214 14 For Less Than Two Million Dollars, 241 You Could Set Half The World Free 15 Death Of A Sailorsman In A Billion Year Time Warp 289 16 History Can Always Be Re-Written 308 17 Crusading For Source Perforce Of Course 325 18 We Always Deliver What We Promise 341 19 When You Yield To Temptation You Always Get Burned 391 20 Charity Doesn't Begin At Home 426 21 If Mary Sue Could Do It, You Can Do It 442 22 It's Easier To Bury One's Mistakes 473 23 Paying The Price For A Fate Worse Than Death 487 24 Earning The Protection Of The Church 522 25 A Race To Get To Sea As The Captain Of A Sinking Ship 542 26 Messiah In The Spin Bin 573 27 Epilogue: Getting Really Clear 602 Footnotes Quoted References of L. -

Scientology in Court: a Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion

DePaul Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 Fall 1997 Article 4 Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion Paul Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Paul Horwitz, Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion, 47 DePaul L. Rev. 85 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENTOLOGY IN COURT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND SOME THOUGHTS ON SELECTED ISSUES IN LAW AND RELIGION Paul Horwitz* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 86 I. THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY ........................ 89 A . D ianetics ............................................ 89 B . Scientology .......................................... 93 C. Scientology Doctrines and Practices ................. 95 II. SCIENTOLOGY AT THE HANDS OF THE STATE: A COMPARATIVE LOOK ................................. 102 A . United States ........................................ 102 B . England ............................................. 110 C . A ustralia ............................................ 115 D . Germ any ............................................ 118 III. DEFINING RELIGION IN AN AGE OF PLURALISM -

The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader

The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader Edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader Edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift Editorial material and organization # 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift to be identified as the Authors of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Blackwell cultural economy reader / edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift. p. cm. – (Blackwell readers in geography) ISBN 0-631-23428-4 (alk. paper) – ISBN 0-631-23429-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Economics–Sociological aspects. I. Amin, Ash. II. Thrift, N. J. III. Series. HM548.B58 2003 306.3–dc21 2003051820 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10/12pt Sabon by Kolam Information Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction x Part I Production 1 1 A Mixed Economy of Fashion Design 3 Angela McRobbie 2 Net-Working for a Living: Irish Software Developers in the Global Workplace 15 Sea´nO´ ’Riain 3 Instrumentalizing the Truth of Practice 40 Katie Vann and Geoffrey C. -

Theire Journal

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 22- 34 TROUBLE IN SCHOOLS FALSE DATA TABLE OF CONTENTS School crime reports discredited; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 official admits ‘we got caught’ By Liz Chandler 4 Hurricanes revive The Charlotte Observer investigative reporting; need for digging deeper NUMBERS GAME By Brant Houston, IRE Reporting of violence varies in schools; accountability found to be a problem 6 OVERCHARGE By Jeff Roberts CAR training pays off in examination and David Olinger of state purchase-card program’s flaws The Denver Post By Steve Lackmeyer The (Oklahoma City) Oklahoman REGISTRY FLAWS Police confusion leads 8 PAY TO PLAY to schools unaware of Money managers for public fund contribute juvenile sex offenders to political campaign coffers to gain favors attending class By Mark Naymik and Joseph Wagner By Ofelia Casillas The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer Chicago Tribune 10 NO CONSENT LEARNING CURVE Families unaware county profiting from selling Special needs kids dead relatives’ brains for private research use overrepresented in city’s By Chris Halsne failing and most violent KIRO-Seattle public high schools By John Keefe 12 MILITARY BOON WNYC-New York Public Radio Federal contract data shows economic boost to locals from private defense contractors LOOKING AHEAD By L.A. Lorek Plenty of questions remain San Antonio Express-News for journalists investigating problems at local schools By Kenneth S. Trump National School Safety and Security Services 14- 20 SPECIAL REPORT: DOING INVESTIGATIONS AFTER A HURRICANE COASTAL AREAS DELUGE OF DOLLARS -

Freedom of Religion and the Church of Scientology in Germany and the United States

SHOULD GERMANY STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE OCTOPUS? FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY IN GERMANY AND THE UNITED STATES Religion hides many mischiefs from suspicion.' I. INTRODUCTION Recently the City of Los Angeles dedicated one of its streets to the founder of the Church of Scientology, renaming it "L. Ron Hubbard Way." 2 Several months prior to the ceremony, the Superior Administrative Court of Miinster, Germany held that Federal Minister of Labor Norbert Bluim was legally permitted to continue to refer to Scientology as a "giant octopus" and a "contemptuous cartel of oppression." 3 These incidents indicate the disparity between the way that the Church of Scientology is treated in the United States and the treatment it receives in Germany.4 Notably, while Scientology has been recognized as a religion in the United States, 5 in Germany it has struggled for acceptance and, by its own account, equality under the law. 6 The issue of Germany's treatment of the Church of Scientology has reached the upper echelons of the United States 1. MARLOWE, THE JEW OF MALTA, Act 1, scene 2. 2. Formerly known as Berendo Street, the street links Sunset Boulevard with Fountain Avenue in the Hollywood area. At the ceremony, the city council president praised the "humanitarian works" Hubbard has instituted that are "helping to eradicate illiteracy, drug abuse and criminality" in the city. Los Angeles Street Named for Scientologist Founder, DEUTSCHE PRESSE-AGENTUR, Apr. 6, 1997, available in LEXIS, News Library, DPA File. 3. The quoted language is translated from the German "Riesenkrake" and "menschenverachtendes Kartell der Unterdruickung." Entscheidungen des Oberver- waltungsgerichts [OVG] [Administrative Court of Appeals] Minster, 5 B 993/95 (1996), (visited Oct. -

Behar-Forbes-1986.Pdf

L. Ron Hubbard, one of the most bizarre entrepreneurs on record, proved cult religion can be big business. Now he's declared dead, and the question is, did he take $200 million with him? The prophet and profits of Scientology There is something that FORBES L. Ron Hubbard gone underground in New York City: 1973 still doesn't know, however. It is something no one may know outside a small, secretive band of Hubbard's followers: What is happening to all that money? Hubbard himself has not been seen publicly since 1980, when he went underground, disappearing even from the view of high "church" officials. That's in character: He was said by spokesmen to have retired from Scientology's management in 1966. In fact, for 20 years after, he maintained a grip so tight that sources say since his 1980 disappearance three appoint ed "messengers" have been able to gather tens of millions of dollars at will, harass and intimidate Scientol ogy members, and rule with an iron fist an international network that is still estimated to have tens of thou sands of adherents—all merely on his unseen authority. How could Hubbard do all this? As early as the 1950s, officials at the American Medical Association were By Richard Behar wife, went to jail for infiltrating, bur glarizing and wiretapping over 100 warning that Scientology, then NLY A FEW CAN BOAST the fi government agencies, including the known as Dianetics, was a cult. More nancial success of L. Ron Hub IRS, FBI and CIA. Hubbard could hold recently, in 1984, courts of law here bard, the science fiction story his own with any of his science fic and abroad labeled the organization O such things as "schizophrenic and teller and entrepreneur who reported tion novels. -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 1 of 111 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, ) Civil Action No. 1:18-cv-03501 ) JURY DEMAND Plaintiff, ) ) SECOND AMENDED v. ) COMPLAINT ) COMPUTER FRAUD AND ABUSE THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION; ) ACT (18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)) ARAS ISKENEROVICH AGALAROV; ) RICO (18 U.S.C. § 1962(c)) EMIN ARAZ AGALAROV; ) ) RICO CONSPIRACY (18 U.S.C. JOSEPH MIFSUD; ) § 1962(d)) WIKILEAKS; ) WIRETAP ACT (18 U.S.C. JULIAN ASSANGE; ) §§ 2510-22) DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, INC.; ) ) STORED COMMUNICATIONS DONALD J. TRUMP, JR.; ) ACT (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12) PAUL J. MANAFORT, JR.; ) DIGITAL MILLENNIUM ROGER J. STONE, JR.; ) COPYRIGHT ACT (17 U.S.C. ) JARED C. KUSHNER; § 1201 et seq.) GEORGE PAPADOPOULOS; ) ) MISAPPROPRIATION OF TRADE RICHARD W. GATES, III; ) SECRETS UNDER THE DEFEND ) TRADE SECRETS ACT (18 U.S.C. Defendants. ) § 1831 et seq.) ) INFLUENCING OR INJURING ) OFFICER OR JUROR GENERALLY ) (18 U.S.C. § 1503) ) ) TAMPERING WITH A WITNESS, ) VICTIM, OR AN INFORMANT (18 ) U.S.C. § 1512) ) WASHINGTON D.C. UNIFORM ) TRADE SECRETS ACT (D.C. Code ) Ann. §§ 36-401 – 46-410) ) ) TRESPASS (D.C. Common Law) ) CONVERSION (D.C. Common Law) ) TRESPASS TO CHATTELS ) (Virginia Common Law) ) ) ) Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 2 of 111 CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT TRESPASS TO CHATTELS (Virginia Common Law) CONVERSION (Virginia Common Law) VIRGINIA COMPUTER CRIMES ACT (Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-152.5 et seq.) 2 Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 3 of 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NATURE OF ACTION .................................................................................................................