Abstract Equipment Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

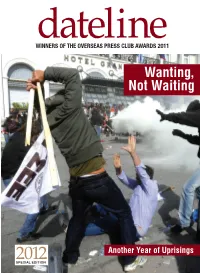

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK RICHARD BEHAR, Plaintiff, V. U.S. DEPARTMENT of HOMELAND

Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 1 of 53 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK RICHARD BEHAR, Plaintiff, Nos. 17 Civ. 8153 (LAK) v. 18 Civ. 7516 (LAK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, Defendant. PLAINTIFF’S MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF CROSS-MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO THE GOVERNMENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT John Langford, supervising attorney David Schulz, supervising attorney Charles Crain, supervising attorney Anna Windemuth, law student Jacob van Leer, law student MEDIA FREEDOM & INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC ABRAMS INSTITUTE Yale Law School P.O. Box 208215 New Haven, CT 06520 Tel: (203) 432-9387 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiff Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 2 of 53 STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT Plaintiff respectfully requests oral argument to address the public’s right of access under the Freedom of Information Act to the records at issue. Case 1:17-cv-08153-LAK Document 34 Filed 10/31/18 Page 3 of 53 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 2 A. Secret Service Protection for Presidential Candidates ....................................................... -

Santa Monica Daily Press 100% Organic News

FREE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 5, 2002 Volume 1, Issue 176 FREE Santa Monica Daily Press 100% organic news. Picked fresh daily. Well-orchestrated Santa Monica Place may be split in two stores and restaurants similar to the set-up Plans call for multi- along the Promenade. million dollar redesign In fact, Macerich representatives said their goal is to create a seamless transition of ‘dinosaur’ mall from the third block of the Promenade through their mall. BY ANDREW H. FIXMER “One wouldn’t realize they were Daily Press Staff Writer entering the mall area,” said Randy Brant, a Macerich senior vice-president. In 10 years, downtown Santa Monica “It would appear as just another block of may be a completely different place. the Promenade.” Plans were unveiled Monday night that However, the connection would mean would extend the Third Street Promenade a lot to Santa Monica officials. They want through the Santa Monica Place Mall, cre- to connect the Civic Center and the ating a pedestrian walkway stretching from Promenade, as well as a future location Wilshire Boulevard to the Civic Center. for the Expo light rail line eventually Though many of the details have not reach the city. been worked out, the Macerich Company “I think many people, like myself, Carolyn Sackariason/Daily Press — which owns and operates the enclosed think of Santa Monica Place as a Members of the Santa Monica High School symphony orchestra receive mall — wants to slice its building in half instruction from Chris Woods, right, a substitute teacher on Tuesday. to create a row of ground floor retail See MALL, page 4 College buys downtown Renters victorious in small claims fight with landlord building for $8.6 million BY ANDREW H. -

Shopping for Religion: the Change in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law, 51 Buff

Buffalo Law Review Volume 51 | Number 1 Article 4 1-1-2003 Shopping for Religion: The hC ange in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law Rebecca French University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Rebecca French, Shopping for Religion: The Change in Everyday Religious Practice and Its Importance to the Law, 51 Buff. L. Rev. 127 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol51/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo chooS l of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shopping for Religion: The Change in Everyday Religious Practice and its Importance to the Law REBECCA FRENCHt INTRODUCTION Americans in the new century are in the midst of a sea- change in the way religion is practiced and understood. Scholars in a variety of disciplines-history of religion, sociology and anthropology of religion, religious studies- who write on the current state of religion in the United States all agree on this point. Evidence of it is everywhere from bookstores to temples, televisions shows to "Whole Life Expo" T-shirts.1 The last thirty-five years have seen an exponential increase in American pluralism, and in the number and diversity of religions. -

Scientology in Court: a Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion

DePaul Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 Fall 1997 Article 4 Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion Paul Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Paul Horwitz, Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion, 47 DePaul L. Rev. 85 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENTOLOGY IN COURT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND SOME THOUGHTS ON SELECTED ISSUES IN LAW AND RELIGION Paul Horwitz* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 86 I. THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY ........................ 89 A . D ianetics ............................................ 89 B . Scientology .......................................... 93 C. Scientology Doctrines and Practices ................. 95 II. SCIENTOLOGY AT THE HANDS OF THE STATE: A COMPARATIVE LOOK ................................. 102 A . United States ........................................ 102 B . England ............................................. 110 C . A ustralia ............................................ 115 D . Germ any ............................................ 118 III. DEFINING RELIGION IN AN AGE OF PLURALISM -

The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader

The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader Edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader Edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift Editorial material and organization # 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift to be identified as the Authors of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Blackwell cultural economy reader / edited by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift. p. cm. – (Blackwell readers in geography) ISBN 0-631-23428-4 (alk. paper) – ISBN 0-631-23429-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Economics–Sociological aspects. I. Amin, Ash. II. Thrift, N. J. III. Series. HM548.B58 2003 306.3–dc21 2003051820 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10/12pt Sabon by Kolam Information Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction x Part I Production 1 1 A Mixed Economy of Fashion Design 3 Angela McRobbie 2 Net-Working for a Living: Irish Software Developers in the Global Workplace 15 Sea´nO´ ’Riain 3 Instrumentalizing the Truth of Practice 40 Katie Vann and Geoffrey C. -

Plaintiff INTERNATIONAL B

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 88 CIV. 4486 (LAP) Plaintiff APPLICATION 101 OF THE v. INDEPENDENT REVIEW BOARD — OPINION AND DECISION OF INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF THE INDEPENDENT REVIEW TEAMSTERS, et al. BOARD IN THE MATTER OF THE HEARING OF Defendants JOSEPH VIGLIOTTI Pursuant to Paragraph O. of the Rules and Procedures for Operation of the Independent Review Board for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters ("IRB Rules") , Application is made by the Independent Review Board ("IRB") for ruling by the Honorable Loretta A. Preska, United States District Judge for the Southern District of New York, on the issues heard by the IRB during a hearing on November 8, 2 001, and thereafter determined, on the charges filed against Joseph Vigliotti ("Vigliotti") , a member of IBT Local 813. Vigliotti was charged with bringing reproach upon the IBT and violating his membership oath by knowingly associating with Peter Gotti, a known member of organized crime. The evidence established just cause for the IRB to find that the charges against Vigliotti were proved. As a penalty, Vigliotti has been permanently barred from holding membership in or any position with the IBT or any IBT-affiliated entity in the future and may not hereafter obtain employment, consulting or other work with the IBT or any IBT-affiliated entity. Enclosed with our March 21, 2 002, Opinion and Decision are the June 12, 2001, IRB Investigative Report with Exhibits 1-23 and the November 8, 2001, IRB Hearing Transcript with exhibits IRB—1 - IRB—7. It is respectfully requested that an Order be entered affirming the IRB's March 21, 2002, Opinion and Decision if Your Honor finds it appropriate. -

Bad to Worse for Peter Gotti

Bad To Worse For Peter Gotti http://www.ganglandnews.com/members/column379.htm April 29, 2004 By Jerry Capeci Bad To Worse For Peter Gotti It’s been a hell of a month for Peter Gotti. His longtime paramour, who had remained anonymous despite her daily attendance at his racketeering trial last year, publicly championed her love for him, then committed suicide after he dressed her down for causing such a big stir. His angry wife threw a monkey wrench into his divorce plans and asked a Brooklyn Federal Court judge to lock him up and throw away the key as punishment for labor racketeering on the Brooklyn waterfront. The judge gave the 64-year-old convicted mob boss nine years and four months. In Manhattan, more crimes – construction industry extortion and plotting to kill turncoat gangster Salvatore (Sammy Bull) Gravano – now threaten to send him away for life. What’s more, while an underling codefendant in the Manhattan case, capo Louis (Big Lou) Vallario, who was charged with taking part in a 1989 murder for then-high-flying Dapper Don John Gotti, just wangled a sweet plea deal, sources say the feds intend to play hardball with Peter and four other defendants. 1 of 5 11/5/2009 9:58 PM Bad To Worse For Peter Gotti http://www.ganglandnews.com/members/column379.htm “We’re really not interested in resuming plea discussions with any of the remaining defendants; we’re preparing for trial,” one member of the prosecution team told Gang Land yesterday. Vallario, (left) whose sentencing guidelines called for 24 to 30 years, faces a maximum of 13 years, according to an agreement worked out last week by defense lawyer James DiPietro and federal prosecutors under U.S. -

Theire Journal

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 22- 34 TROUBLE IN SCHOOLS FALSE DATA TABLE OF CONTENTS School crime reports discredited; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 official admits ‘we got caught’ By Liz Chandler 4 Hurricanes revive The Charlotte Observer investigative reporting; need for digging deeper NUMBERS GAME By Brant Houston, IRE Reporting of violence varies in schools; accountability found to be a problem 6 OVERCHARGE By Jeff Roberts CAR training pays off in examination and David Olinger of state purchase-card program’s flaws The Denver Post By Steve Lackmeyer The (Oklahoma City) Oklahoman REGISTRY FLAWS Police confusion leads 8 PAY TO PLAY to schools unaware of Money managers for public fund contribute juvenile sex offenders to political campaign coffers to gain favors attending class By Mark Naymik and Joseph Wagner By Ofelia Casillas The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer Chicago Tribune 10 NO CONSENT LEARNING CURVE Families unaware county profiting from selling Special needs kids dead relatives’ brains for private research use overrepresented in city’s By Chris Halsne failing and most violent KIRO-Seattle public high schools By John Keefe 12 MILITARY BOON WNYC-New York Public Radio Federal contract data shows economic boost to locals from private defense contractors LOOKING AHEAD By L.A. Lorek Plenty of questions remain San Antonio Express-News for journalists investigating problems at local schools By Kenneth S. Trump National School Safety and Security Services 14- 20 SPECIAL REPORT: DOING INVESTIGATIONS AFTER A HURRICANE COASTAL AREAS DELUGE OF DOLLARS -

Gambino Organized Crime Family of La Cosa Nostra Other LCN Family

Gambino Organized Crime Family of La Cosa Nostra Peter Gotti John D’Amico Domenico Cefalu Joseph Corozzo BOSS ACTING BOSS ACTING UNDERBOSS CONSIGLIERE Convicted of Racketeering Charged with Racketeering Charged with Racketeering Charged with Racketeering including Murder Conspiracy including including including and Money Laundering Extortion / Extortion Conspiracy Extortion / Extortion Conspiracy Extortion and Cocaine Trafficking Serving Life Imprisonment Faces 20 Years Imprisonment Faces 20 Years Imprisonment Faces Life Imprisonment Thomas Cacciopoli Nicholas Corozzo Leonard DiMaria George DeCicco Dominick Pizzonia Captain Captain Captain Captain (Convicted) Captain (Convicted) Faces 20 Years Faces Life Faces 20 Years Awaiting Sentence Awaiting Sentence Frank Cali Augustus Sclafani Louis Filippelli Acting Captain Acting Captain Acting Captain Faces 20 Years Faces 20 Years Faces 20 Years Jerome Charles Mario Joseph Vincent Robert Richard G. Vincent Ernest Brancato Carneglia Cassarino Chirico Dragonetti Epifania Gotti Gotti Grillo Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider John Richard Joseph Anthony James Vincent Angelo Joseph William Gammarano Juliano Orlando Licata Outerie Pacelli Ruggiero Jr. Scopo Scotto Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider Solider (Convicted) (Convicted) (Convicted) Other LCN Family and Construction / Union Defendants Construction Industry Labor Unions Bonanno Family Genovese Family Anthony Delvescovo Michael King Vincent Amarante Nicholas Calvo Schiavone Construction Laborers’ Local 731 Soldier Associate Steven Sabella Sarah Dauria Louis Mosca Michael Urciuoli SRD Contracting Laborers’ Local 325 Associates. -

Freedom of Religion and the Church of Scientology in Germany and the United States

SHOULD GERMANY STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE OCTOPUS? FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY IN GERMANY AND THE UNITED STATES Religion hides many mischiefs from suspicion.' I. INTRODUCTION Recently the City of Los Angeles dedicated one of its streets to the founder of the Church of Scientology, renaming it "L. Ron Hubbard Way." 2 Several months prior to the ceremony, the Superior Administrative Court of Miinster, Germany held that Federal Minister of Labor Norbert Bluim was legally permitted to continue to refer to Scientology as a "giant octopus" and a "contemptuous cartel of oppression." 3 These incidents indicate the disparity between the way that the Church of Scientology is treated in the United States and the treatment it receives in Germany.4 Notably, while Scientology has been recognized as a religion in the United States, 5 in Germany it has struggled for acceptance and, by its own account, equality under the law. 6 The issue of Germany's treatment of the Church of Scientology has reached the upper echelons of the United States 1. MARLOWE, THE JEW OF MALTA, Act 1, scene 2. 2. Formerly known as Berendo Street, the street links Sunset Boulevard with Fountain Avenue in the Hollywood area. At the ceremony, the city council president praised the "humanitarian works" Hubbard has instituted that are "helping to eradicate illiteracy, drug abuse and criminality" in the city. Los Angeles Street Named for Scientologist Founder, DEUTSCHE PRESSE-AGENTUR, Apr. 6, 1997, available in LEXIS, News Library, DPA File. 3. The quoted language is translated from the German "Riesenkrake" and "menschenverachtendes Kartell der Unterdruickung." Entscheidungen des Oberver- waltungsgerichts [OVG] [Administrative Court of Appeals] Minster, 5 B 993/95 (1996), (visited Oct. -

Behar-Forbes-1986.Pdf

L. Ron Hubbard, one of the most bizarre entrepreneurs on record, proved cult religion can be big business. Now he's declared dead, and the question is, did he take $200 million with him? The prophet and profits of Scientology There is something that FORBES L. Ron Hubbard gone underground in New York City: 1973 still doesn't know, however. It is something no one may know outside a small, secretive band of Hubbard's followers: What is happening to all that money? Hubbard himself has not been seen publicly since 1980, when he went underground, disappearing even from the view of high "church" officials. That's in character: He was said by spokesmen to have retired from Scientology's management in 1966. In fact, for 20 years after, he maintained a grip so tight that sources say since his 1980 disappearance three appoint ed "messengers" have been able to gather tens of millions of dollars at will, harass and intimidate Scientol ogy members, and rule with an iron fist an international network that is still estimated to have tens of thou sands of adherents—all merely on his unseen authority. How could Hubbard do all this? As early as the 1950s, officials at the American Medical Association were By Richard Behar wife, went to jail for infiltrating, bur glarizing and wiretapping over 100 warning that Scientology, then NLY A FEW CAN BOAST the fi government agencies, including the known as Dianetics, was a cult. More nancial success of L. Ron Hub IRS, FBI and CIA. Hubbard could hold recently, in 1984, courts of law here bard, the science fiction story his own with any of his science fic and abroad labeled the organization O such things as "schizophrenic and teller and entrepreneur who reported tion novels.