John Ford's Cavalry Trilogy: Myth Or Reality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Only Kly Ic Ori Lm

THE SUN AY THJ SEY'S ONLY KLY IC ORI L M INE - ':.....:.:::...::.:...:.i'..'%.:::::.•:::?i:?:i:i::::.:..':::i.•:i:i:i:i.i:i:i.i:i:!:i:•:!:i:!::':': "' .:•.•:i:i:i:?:•:•:•.i:ii!:•:i:i:i:iii:ii•:i:iii:?!!i!:!i•ii??i•?i:i?i•i?!!:iii:ii?:•:?i•!??•?!•i:i•i:?:i:•:i:i•i:::::!:i::.:: .::.. '.: :•?:•::•i!ii::i!::?:• .......i::ii• !•ili!•!!iil ii•i• ! ::; ! •iii!i• ii• i ili !i:: •ii i::ii •ii:: :•?:i!ii• ii:: •ii!i!iii!!::•..':•.::::':'::iii::! i!i• :: ::. "•;.:. .... :•:i:: ':-'!!i::ii::?:" ::::'•'."• :'??:::'::•:•:::i?•:?. ':. ?'•:•' ;'i:.;i•:•!!i!'':•:: ::!iif!:: i ::::i::ii?:ii i:ß ii :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::! i f i :.i• !i •i ::ii !i::i :::i•J•i:: i!i!i i!:: i!i ::::i•ili!! i! ::ii:: ::!i!::ii?: ii :: ii::•iii !!.::•i i.i i•:•iß:: ?:•i•>?::i•ii..:i'•i:•.i•i.:•i •i:: •:i i •..: .... i:.. •i•?:•ii?:•::•,:•:i ::i ii ii:: iii•...... ß ............ ':: :i::::: :::::::::::::::::::::::i?:•::!::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ..... : . ::::::::::::" g?:-.:.::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: :i::•: :: :?:•::::.:::::::::: ...... ß :!:--::::?:?:?::i:!:?:?:::::: .. ::::::::::::::::::::::::: :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::==================================================================================================================================:?::i:::?: :?'..... •':-i'-::•:•;•!ii:'::::•:.::.::i:?: :i: :i:?:?:?: :?:?:?:i:?: ........: ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – Discovermoab.Com - 8/21/01 Page 1

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – discovermoab.com - 8/21/01 Page 1 Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours Discovermoab.com Internet Brochure Series Moab Area Travel Council The Moab area has been a filming location since 1949. Enjoy this guide as a glimpse of Moab's movie past as you tour some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. All movie locations are accessible with a two-wheel drive vehicle. Locations are marked with numbered posts except for locations at Dead Horse Point State Park and Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. Movie locations on private lands are included with the landowner’s permission. Please respect the land and location sites by staying on existing roads. MOVIE LOCATIONS FEATURED IN THIS GUIDE Movie Description Map ID 1949 Wagon Master - Argosy Pictures The story of the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers who Director: John Ford hire Johnson and Carey as wagonmasters to lead 2-F, 2-G, 2-I, Starring: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey, Jr., them to the San Juan River country 2-J, 2-K Ward Bond. 1950 Rio Grande - Republic Reunion of a family 15 years after the Civil War. Directors: John Ford & Merian C. Cooper Ridding the Fort from Indian threats involves 2-B, 2-C, 2- Starring: John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Ben Johnson, fighting with Indians and recovery of cavalry L Harry Carey, Jr. children from a Mexican Pueblo. 1953 Taza, Son of Cochise - Universal International 3-E Starring: Rock Hudson, Barbara Rush 1958 Warlock - 20th Century Fox The city of Warlock is terrorized by a group of Starring: Richard Widmark, Henry Fonda, Anthony cowboys. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

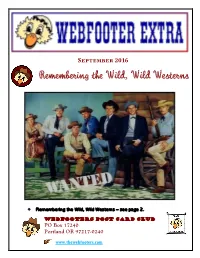

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 65, Number 1, December 1983

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications 12-1983 Maine Alumnus, Volume 65, Number 1, December 1983 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 65, Number 1, December 1983" (1983). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 337. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/337 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. xr* • c alumnus I ‘ t 4. ’ - 9 .-•■ • x • Mail-order church goods— big business for Michael<, Fendler '74 « r « I _ 9. * 'S * r i BILL JOHNSON '56 is one of the University of Maine at Orono's top salesmen. When he is at the University, which isn't often, the president of the Alumni Council bounds up the steps of Crossland Alumni Center and reaches the administrative offices of the Alumni Association by 7 a.m. When he is traveling, which is often, Johnson is "up and cracking early," relating the University's fundraising needs to alumni and friends. He usually finds a receptive audience. 1 "The University has contributed a lot to experiences that have helped me in the business world," said Johnson, district sales manager for Mobil Oil Corporation. "I want to return a small portion of what UMO has done for me." By that standard, Johnson may be a consummate "UMO man." He describes himself as enthusiastic and competitive. -

Modernity and the Film Western

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-07-02 "No Goin' Back": Modernity and the Film Western Julie Anne Kohler Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kohler, Julie Anne, ""No Goin' Back": Modernity and the Film Western" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4152. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “No Goin’ Back”: Modernity and the Film Western Julie Anne Kohler A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Kerry Soper, Chair Carl Sederholm George Handley Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature Brigham Young University July 2014 Copyright © 2014 Julie Anne Kohler All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “No Goin’ Back”: Modernity and the Film Western Julie Anne Kohler Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature, BYU Master of Arts This thesis is inspired by an ending—that of a cowboy hero riding away, back turned, into the setting sun. That image, possibly the most evocative and most repeated in the Western, signifies both continuing adventure and ever westward motion as well as a restless lack of final resolution. This thesis examines the ambiguous endings and the conditions leading up to them in two film Westerns of the 1950s, George Steven’s Shane (1953) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). -

Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Sociology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds Recommended Citation Halbgewachs, Nancy Copeland. "Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Candidate Department of Sociology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. George A. Huaco , Chairperson Dr. Richard Couglin Dr. Susan Tiano Dr. James D. Stone i CENSORSHIP AND HOLOCAUST FILM IN THE HOLLYWOOD STUDIO SYSTEM BY NANCY COPELAND HALBGEWACHS B.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1962 M.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1966 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2011 ii DEDICATION In memory of My uncle, Leonard Preston Fox who served with General Dwight D. Eisenhower during World War II and his wife, my Aunt Bonnie, who visited us while he was overseas. My friend, Dorothy L. Miller who as a Red Cross worker was responsible for one of the camps that served those released from one of the death camps at the end of the war. -

Tamms Correctional Center

Tamms Correctional Center Public Comments As of 05/21/2012 WRITTEN STATEMENT OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION Hearing on the Proposed Closure of Tamms Correctional Center Submitted to the Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability April 2, 2012 ACLU National Prison Project ACLU of Illinois David Fathi, Director Mary Dixon, Legislative Director The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), founded in 1920, is a nationwide, non-profit, nonpartisan organization of more than 500,000 members dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality embodied in the Constitution and this nation's civil rights laws. Since 1972 the ACLU National Prison Project has worked to ensure that our nation’s prisons comply with the Constitution, domestic law, and international human rights principles. The American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organization committed to protect and to expand the civil liberties and civil rights of persons in Illinois. The organization has engaged in this constitutionally protected pursuit through public education and advocacy before courts, legislatures, and administrative agencies. The organization has more than 20,000 members and supporters dedicated to protecting and expanding the civil rights and civil liberties guaranteed by the Constitutions and civil rights laws of the United States and the State of Illinois. The ACLU respectfully urges the Commission to approve the permanent closure of Tamms Correctional Center. The damaging effects of solitary confinement are -

The Montana Kaimin, February 25, 1938

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 2-25-1938 The onM tana Kaimin, February 25, 1938 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "The onM tana Kaimin, February 25, 1938" (1938). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 1625. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/1625 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY, MISSOULA, MONTANA Z400 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 25,1938. VOLUME XXXVII. No. 37 Interscholastic Sorority Rushing Split Campus Reverend Warford Resigns WHO’S T r a ck D a tes To Be Allowed After March 1 University Religion Position In the News Are Changed 9 9 Joyce Roberts, president, an Pastor Will Devote Time to Congregational Church; • • nounced yesterday that Pan- Has Been Faculty Member Four Years Saturday, May 14, Will Be hellenic council will allow rush ing and pledging March 1 for As Professor of Theology Concluding Day the rest of the school year. Entertainer Reverend O. R. Warford has resigned his position as inter Of Meet Women who have not yet paid the Panhelienic rushing fee may church pastor to students and director of the Montana School Saturday, May 14, will be the do so March 1 and any time after of Religion.