Utah Coal Industry, from Material on File in the Offices of Some of the Operating Companies, and from Interviews with Many Persons Connected with the Itlining of Coal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Utah State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 Utah

2014 Utah State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan UTAH STATE PARKS Division of Utah State Parks and Recreation Planning Section 1594 West North Temple, Ste. 116 P.O. Box 146001 Salt Lake City, UT 84116-6001 (877) UT-PARKS stateparks.utah.gov State of Utah Figure 1. Public land ownership in Utah. ii 2014 SCORP ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research and publication of the 2014 Utah State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) is a product of a team effort. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Division of Utah State Parks and Recreation, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah Department of Transportation, Utah Division of Water Resources, Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, National Park Service (Omaha Regional Office), U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, Utah League of Cities and Towns, Utah Association of Counties, Utah Recreation and Parks Association, and others provided data, information, advice, recommendations, and encouragement. The 2014 Utah SCORP was completed under contract by BIO-WEST, Inc. (BIO-WEST), with survey work completed by Dan Jones & Associates. Key project contributors include Gary Armstrong, project manager for BIO-WEST, and David Howard, lead survey research associate for Dan Jones & Associates. Susan Zarekarizi of the Division of Utah State Parks and Recreation served as the overall project manager and provided contractor oversight. Additional staff contributing to the project include Sean Keenan of BIO-WEST, and Tyson Chapman and Kjersten Adams of Dan Jones & Associates. The 2014 Utah SCORP represents demand for future recreation facilities as identified in a series of public opinion surveys, special reports, park surveys, federal and local plans, technical reports, and other data. -

Performance and Contributions of the Green Industry to Utah's Economy

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2021 Performance and Contributions of the Green Industry to Utah's Economy Lara Gale Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Gale, Lara, "Performance and Contributions of the Green Industry to Utah's Economy" (2021). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 1551. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/1551 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERFORMANCE AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE GREEN INDUSTRY TO UTAH’S ECONOMY by Lara Gale A research paper submitted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Applied Economics Approved: ____________________________ ______________________________ Man Keun Kim, Ph.D. Ruby Ward, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ Larry Rupp, Ph.D. Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii ABSTRACT PERFORMANCE AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE GREEN INDUSTRY TO UTAH’S ECONOMY by Lara Gale, MS in Applied Economics Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Man Keun Kim Department: Applied Economics Landscaping and nursery enterprises, commonly known as green industry enterprises, can be found everywhere in Utah, and are necessary to create both aesthetic appeal and human well-being in the built environment. In order to understand the impact that events such as economic shocks or policy changes may have on the green industry, the baseline performance and contribution of the industry must be specified for comparison following these shocks. -

Economic Contribution of Agriclture to the Utah Economy 2014

The Economic Contribution of Agriculture to the Utah Economy in 2014 Ruby A. Ward Professor Karli Salisbury Research Assistant Dept. of Applied Economics Utah State University UMC 4835 Logan, UT 84322-4835 Prepared for Utah Department of Agriculture and Food Utah State University Economic Research Institute Report #2016-01 October 2016 Situation • The study of the economic contribution of agriculture to the Utah economy defines agriculture as the combination of the agriculture production sectors (NAICS codes 111, 112 and 115) and the agriculture processing sectors (NAICS codes 311 and 312). • Our economic analysis captures the direct sales (output) of agriculturally oriented businesses within the state, as well as the indirect and induced (multiplier) effects of these expenditures. Analysis was conducted using Version 3 of the Impact Analysis for Planning (IMPLAN) model and its 2014 database. • In 2014, production agriculture, including farming, ranching, dairy, and other related support industries, accounted for over $2.4 billion in direct output (sales), with a total of $3.5 billion in total economic output after adjustment for multiplier effects. - Based on Utah’s 2014 Gross State Product of $140 billion, production agriculture directly accounts for 1.7% of total state output and accounts for 2.5% with multiplying effects. - The production agriculture sector directly employs 18,000 people in either full or part-time positions. When including the multiplying effect, production agriculture accounts for roughly 26,000 jobs with an income compensation of $583 million. • Total direct output by the agricultural processing sector was approximately $10.7 billion in 2014. • The agriculture processing sector and the production agriculture sector combined account for $21.2 billion in total economic output in Utah after adjusting for multiplier effects. -

Airport Report.Indd

SALT LAKE CITY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRPORT REDEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS September 2018 Table of Contents i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction and Summary 1 A. Project Background 1 B. State of the Utah Economy 2 C. Past Studies Summary 2 II. Methodology and Findings 3 A. Data Sources 3 B. Airport Redevelopment Program Description 3 C. Impact of Airport Redevelopment Program 4 D. Direct, Indirect and Induced Impacts of the Airport Redevelopment Program 5 i. Direct 5 ii. Indirect 5 iii. Induced 5 iv. Indirect and Induced 5 E. Estimated Benefit by Industry 6 III. Conclusion 7 IV. Appendix A – Economic Impacts Inputs 8 V. Appendix B – Annual Impacts by Sub-Project 9-12 A. Direct 9 B. Indirect 10 C. Induced 11 D. Indirect and Induced 12 VI. Appendix C - Past Studies of the Airport’s Economic Impact 13-14 Airport Redevelopment Program Economic Impact Analysis // GSBS Consulting Table of Tables iii TABLE OF TABLES TABLE 1 Terminal Redevelopment Program Analysis vs Airport Redevelopment Program Analysis TABLE 2 Annualized ARP Impact TABLE 3 ARP Annual Average Impact by Year TABLE 4 ARP Total Induced and Indirect Impact 2013-2025 TABLE 5 Total Impact Airport Redevelopment Program 2013-2025 TABLE 6 Top Ten Industries Impacted Statewide by Employment TABLE 7 Top Ten Industries Impacted Statewide by Total Output TABLE 8 Total Estimated Annual Direct Spending from All Projects TABLE 9 Total Annual Indirect Spending from All Projects TABLE 10 Total Annual Induced Spending from All Projects TABLE 11 Total Annual Indirect and Induced Spending from All Projects Airport Redevelopment Program Economic Impact Analysis // GSBS Consulting Introduction and Summary 1 I. -

Collaborative Development of Narratives and Models for Steering Inter-Organizational Networks Philip C

Collaborative Development of Narratives and Models for Steering Inter-Organizational Networks Philip C. Emmi, Craig B. Forster, Jim I. Mills, Tarla Rai Peterson, Jessica L. Durfee and Frank X. Lilly University of Utah College of Architecture + Planning 375 S. 1530 East, Room 235 AAC Phone: 1-801-581-4255 Fax: 1-801-581-8217 [email protected] Abstract The power to direct and manage change within metropolitan areas is increasingly dispersed among a loosely interconnected set of mostly local organizations, agencies and actors that form a special type of urban inter-organizational network. Increasingly, the quality of metropolitan regional governance depends upon IO network capacity to articulate systemically insightful urban development strategies, i.e., to exercise a capacity for network steering. We outline an IO network steering capacity-support process that combines collaborative learning, narrative storytelling, and system dynamics modeling with the goal of deepening insights into urban human/biophysical processes and securing greater resilience in metropolitan regional governance. Our process promotes comprehension of complex urban processes through stories about past trajectories and future growth scenarios that frame issues within collaborative learning workshops for deliberation by local opinion leaders. This initiative is part of a larger research study on greenhouse gas emissions in relation to human and biological activities within metropolitan areas. Keywords: Collaborative learning, narratives, system dynamics, steering inter- organizational networks Introduction As our conception of government and its capacity for societal guidance changes, so too, does our approach to planning and decision-making. Increasingly, we recognize that the power to guide and direct change is dispersed among a variety of loosely interconnected organizations, agencies and actors. -

Meadow, Millard County, Utah: the Geography of a Small Mormon Agricultural Community

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1966 Meadow, Millard County, Utah: the Geography of a Small Mormon Agricultural Community Richard H. Jackson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Jackson, Richard H., "Meadow, Millard County, Utah: the Geography of a Small Mormon Agricultural Community" (1966). Theses and Dissertations. 4820. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4820 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MEADOW MILLARD county1COUNTY UTAH THE GEOGRAPHY OF A SMALL MORMON agricultural COMMUNITY A thesis presented to the department of geography brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of science by richard H jackson august 1966 acknowledgementacknowledgementsS sincere apnrecappreciationiationbation is expressed for the help of many who contributed to this thesis both directly and indirectly special gratitude is expressed to doctor alan H grey of the geography department whose guidance and suggestions greatlgreatagreatlyy facilitated writing of the thesis appreciation is also expressed to doctor george M addy of the history department and to the members of -

Wildfire in Utah

Wildfire in Utah UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Wildfire in Utah The Physical and Economic Consequences of Wildfire Paul M. Jakus, Editor 2/10/2017 Project Authors: Paul M. Jakus Man-Keun Kim Department of Applied Economics Center for Society, Economy, and the Environment Randy C. Martin Ian Hammond Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Utah Water Laboratory Edd Hammill Nancy Mesner Jacob Stout Department of Watershed Resources Ecology Center 1 The Physical and Economic Consequences of Wildfire PRELUDE On June 26, 2012 a lightning strike ignited a wildfire in the Manti-La Sal National Forest of central Utah’s Carbon and Emery counties (Figure P.1). By the time the Seeley wildfire was contained three weeks later, some 48,000 acres of federal, state, and private land had been burned and $8.7 million in suppression costs expended (Styler 2012). According to the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS.gov) project, nearly one-third of the acreage was severely burned, damaging vegetation and soils for years to come. Severe burns vastly increase the erosion potential of burnt landscapes, and the steep lands of Huntington Canyon proved to be no exception. Figure P.1: Smoke from the Seeley wildfire. Source: Inciweb.nwcg.gov Subsequent thunderstorm events caused dangerous landslides as debris flows composed of water, boulders, gravel, sand, tree trunks, and ash scoured soils down to bare rock (Giraud and McDonald, 2013; Figure P.2). The flows also increased erosion in Huntington Creek and severely damaged State Highway 31, which was subsequently closed often due to debris and washouts. The debris-filled wa- ter also threatened drinking water supplies in Huntington City and cooling water used in the Hun- tington Power Plant. -

1996 Economic Report to the Governor

State of Utah Michae 0. Leavitt, Governor Second Printing Governor's Office of Planning and Budget January 1996 116 State Capitol Salt Lake City, UT 841 14 STATEOF UTAH MICHAEL 0.LEAVITT OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR OLENE S. WALKER GOVERNOR SALT LAKE CITY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR 841 14-0601 January 8, 1996 My Fellow Utahns: I am pleased to accept this annual report on Utah's economic performance. I want to thank the State Economic Coordinating Committee for preparing this careful assessment of the past year and helping to develop and disseminate a consistent foundation of economic data and analysis. As I have met with state economists and reviewed the economic data, I am impressed and humbled by the prosperity of the era. The Economic Coordinating Committee has aptly characterized the past several years as a golden period for the Utah economy. These are the best of times. We celebrate our centennial year with low unemployment, rising incomes, and a budget surplus. And while some would credit Utah's economic performance to good fortune or timing -- and there is some of this -- I know the explanation runs deeper. The explanation is found in our people. The productivity of Utah's workers, the wise investments of Utah's entrepreneurs, the first-rate performance of Utah's teachers, the success of Utah companies in the global economy, and the prudent choices made by Utah's leaders are just some, of the many, explanations for our economic accomplishments. I congratulate the residents of this state for their contributions to our collective economic success. During 1995, we survived the Base Realignment and Closure Commission's decisions, learned that Salt Lake City would host the 2002 Winter Olympics and permitted construction for $2.9 billion in projects. -

Recommended State Water Strategy

Recommended State Water Strategy July 2017 Recommended State Water Strategy July 2017 Compiled by the Governor’s Water Strategy Advisory Team Invited by The Honorable Gary R. Herbert Governor, State of Utah Facilitated by Envision Utah Executive Summary Utah faces a daunting challenge. We have the distinction of being both one of the driest states in the nation and one of the fastest growing. At the convergence of those two realities is the challenge of providing water for a population that is projected to nearly double by 2060 while maintaining strong farms and industries and healthy rivers, lakes, wetlands, and aquifers. This challenge is magnified by climate projections from the State Climatologist that show a significant decrease in Utah’s snowpack, which presently provides more annual water storage capacity than all of Utah’s human-made reservoirs combined. In 2013, Governor Gary R. Herbert invited a group of stakeholders with extensive backgrounds in various aspects of water and with a diverse set of perspectives to form the State Water Strategy Advisory Team.1 He tasked them to (1) solicit and evaluate potential water management strategies; (2) frame various water management options and the implications of those options for public feedback; and, (3) based on broad input, develop a set of recommended strategies and ideas to be considered as part of a 5O-year water plan. Despite the often-contentious nature of water policy debate, the Team engaged in earnest discussion and reached agreement on the set of critical issues and strategy recommendations contained in this document, that if studied and advanced will help ensure a vibrant and sustainable water future. -

How Did the Transcontinental Railroad Change Utah's Economy?

How did the Transcontinental Railroad Change Utah’s Economy? GRADE 4 How did the Transcontinental Railroad Change Utah’s Economy? By Rebecca Kirkman Summary Students will read about how the railroad changed Utah’s economy. The students will write a letter as an immigrant farmer or miner to their friends and families about how the railroad has changed Utah’s economy. Main Curriculum Tie UT Standard 2.6 Students will explain how agriculture, railroads, mining, and industrialization created new communities and new economies throughout the state. Time Frame One to two time periods that run 45 minutes each Group Size Individual or pairs Life Skills _ Aesthetics _ Character X Communication _ Employability _ Social & Civic Responsibility X Systems Thinking X Thinking & Reasoning Bibliography Arrington, Leonard J. “The Transcontinental Railroad and the Development of the West.” Utah Historical Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1, Jan. 1969. Christensen, Michael E. “Industries in Utah.” Utah History Encyclopedia, UEN, www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/s/SERVICE_INDUSTRIES.shtml. Haymond, Jay M. “Transportation.” Utah History Encyclopedia, UEN , www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/t/TRANSPORTATION.shtml. Notarianni, Philip F. “Mining.” Utah History Encyclopedia, UEN, https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/m/MINING.shtml Strack, Don. “Railroads in Utah.” Railroads in Utah, Utah History to Go, historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/mining_and_railroads/railroadsinutah.html. Spielmaker, Debra. “Changes & Challenges (1840s-1880s): Era of Self-Sufficiency.” Utah Agriculture in the Classroom, Utah State University Extension, utah.agclassroom.org/matrix/lessonplan.cfm?lpid=555. Page | 2 Materials How the Railroad Changed Utah’s Economy Readings How the Railroad Changed Utah's Economy R.A.F.T. -

Table of Contents

UTAH COUNTY DRAFT Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................3 Land Use............................................................................................................................................6 Economic Considerations .................................................................................................................11 Agriculture.......................................................................................................................................13 Air Quality .......................................................................................................................................18 Canals + Ditches...............................................................................................................................22 Cultural, Historical, Paleontological, and Geological..........................................................................25 Energy Resources.............................................................................................................................31 Fire Management.............................................................................................................................35 Fisheries ..........................................................................................................................................39 Floodplains + River Terraces.............................................................................................................43 -

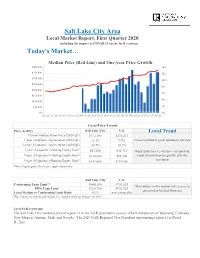

Q1 2020 TEMPLATE.Xlsm

Salt Lake City Area Local Market Report, First Quarter 2020 including the impact of COVID-19 on the local economy Today's Market… Median Price (Red Line) and One-year Price Growth $400,000 14% $350,000 12% $300,000 10% $250,000 8% $200,000 6% $150,000 4% $100,000 $50,000 2% $0 0% 2011 Q1 Q3 2012 Q1 Q3 2013 Q1 Q3 2014 Q1 Q3 2015 Q1 Q3 2016 Q1 Q3 2017 Q1 Q3 2018 Q1 Q3 2019 Q1 Q3 2020 Q1 Local Price Trends Price Activity Salt Lake City U.S. Local Trend Current Median Home Price (2020 Q1) $372,100 $272,433 1-year (4-quarter) Appreciation (2020 Q1) 12.3% 7.7% Prices continue to grow relative to last year 3-year (12-quarter) Appreciation (2020 Q1) 30.7% 18.1% 3-year (12-quarter) Housing Equity Gain* $87,300 $41,733 Gains in the last 3 years have extended the 7-year (28 quarters) Housing Equity Gain* $154,200 $96,500 trend of positive price growth after the recession 9-year (36 quarters) Housing Equity Gain* $181,600 $114,500 *Note: Equity gain reflects price appreciation only Salt Lake City U.S. Conforming Loan Limit** $600,300 $726,525 Most buyers in this market have access to FHA Loan Limit $388,700 $726,525 government-backed financing Local Median to Conforming Limit Ratio 62% not comparable Note: limits are current and include the changes made on January 1st 2019. Local NAR Leadership The Salt Lake City market is part of region 11 in the NAR governance system, which includes all of Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada.