The Horological Legacy of Stanley John Wise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Paper: the KCC Scientific Model 1900W-UNV Clock Winder for Standard Electric Clocks Ken Reindel, KCC Scientific Updated 1-26-13

White Paper: The KCC Scientific Model 1900W-UNV Clock Winder For Standard Electric Clocks Ken Reindel, KCC Scientific Updated 1-26-13 The purpose of this White Paper is to help provide some background on Standard Electric Time master clock, what a Model 1900W-UNV Clock Winder can do for it, and how the Model 1900W-UNV works. Historical Perspective. From the 1880s and beyond, inventors became interested in applying the principles of telegraphy to horology. The idea of a battery-wound master clock which would drive multiple slave clocks, effectively communicating the time signal to them, began to take shape. Additionally, it became fascinating to inventors that the “slave” clocks could be very simple with no escapements or springs, no internal batteries, and requiring little if any maintenance. Charles Warner, who founded the Standard Electric Time Company in 1884,1 was one such inventor. Very early on, Standard Electric borrowed heavily from the Self Winding Clock Company for the design of its master clock movements. Master clocks would have the characteristics described above and relied on special contacts to drive the slaves. Later on, this same concept would be extended to driving program wheels and punched tape ribbons within the clocks themselves, to provide bell timing and other electrical sequences to businesses, schools, etc. For example, many such clocks have been found in schoolhouses and were at one time responsible for ringing bells at the proper times throughout different parts of the building to send students to the next class, as well as driving classroom slave clocks. Standard Electric’s master clock movements eventually took a shape similar to that of the slave clocks: simple, elegant minute impulse ratchet designs for winding the 60, 72, or 80 beat pendulum movements. -

Remembering the First Battery-Operated Clock

© 2015 Antiquarian Horological Society. Reproduction prohibited without permission. ANTIQUARIAN HOROLOGY Remembering the first battery-operated clock Beverley F. Ronalds* Francis Ronalds invented a reliable electric clock in 1815, twenty-five years before Alexander Bain’s patent. It was powered by dry piles, a modified form of battery that has extremely long life but the disadvantage that its electrical properties vary with the weather. Ronalds had considerable success in creating regulating mechanisms for his clock to ensure accurate time-keeping in all meteorological conditions. He did not go on to commercialise his ideas, although others made and sold comparable timepieces on the Continent. This year marks the bicentenary of the with the electrically dissimilar metals. The publication of the first battery-operated dry pile was found to have an electric clock. It was rediscovered in the 1970s by potential difference or voltage across its two Charles Aked, Council member of the ends but, unlike Volta’s pile, did not exhibit Antiquarian Horology Society and first an electric current when the terminals were Chairman of the Electrical Horology Group, joined in a circuit. Its potential difference and further information has since come to was also maintained in use whereas a voltaic hand.1 pile ceased to work after a while.3 The clock was created by a prolific Two of the scientists in England who inventor named (later Sir) Francis Ronalds developed and improved the dry pile were FRS (1788–1873); he lived on the Upper Jean-André de Luc (1727–1817) and Mall in Hammersmith, London, at the time George Singer (1786–1817). -

CLOCKS – TIMERS ASTROTECH QUARTZ CHRONOM E TERS SUPERCLOCK from a Fine Quality Instrument to Satisfy All Cockpit Clock/Timer Needs

CLOCKS – TIMERS ASTROTECH QUARTZ CHRO NOM E TERS SUPERCLOCK FROM A fine quality instrument to satisfy all cockpit clock/timer needs. 12 or 24 hour clock, 24 hour elapsed timer with time- ELECTRONICS INTERNATIONAL Displays local and Zulu time. May be set to display in a 12 out or hold feature, month and date. Will operate on internal or 24-hr format. A 10-year lithium battery keeps the clock CM battery for 2 years or can be connected to electrical system. running even if the aircraft battery is removed. Displays an 12 or 28V DC operation. Up Timer. This Timer will start running when the engine Part no. Model Description Price is started. In this manner the Timer acts as an automatic Flight Timer. 10-15508 LC-2 Panel Mount Aircraft Powered 14/28V . The Up Timer may be started, stopped or reset. A Recurring Alarm may 10-15515 LC-2 Aircraft Powered Panel Clock 28V . be set to alert you at appropriate time intervals. Example: If the alarm is WP 10-15512 LC-2A-5 King Air, 28 volts . set for 30 minutes, you will get an alarm at 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 90 10-15513 LC-2A-6 Beechcraft 28V Clock . minutes, etc. This alarm can be used to remind you to check your fuel 10-15514 LC-2E Embaraer 5V CLOCKClock . level or switch tanks at set time intervals. Displays a Down Timer. This 10-15507 LC-2P Central Wheel 14V A/C Powered . Timer counts down from a programmed start time. The Down Timer may NOTE: For Aircraft Application Information on Astrotech Chronometers visit be started, stopped or reset. -

Variable Time and the Variable Speed of Light Edward G

Variable Time and the Variable Speed of Light Edward G. Lake Independent Researcher August 14, 2018 [email protected] Abstract: Einstein’s Special and General Theories of Relativity state that time is a variable depending upon motion and gravity. The theories also state that the speed of light is variable. Einstein’s theories are being verified virtually every day. Yet, a few physicists still argue that time does not vary, and many physicists appear to inexplicably argue that Einstein’s theories state that the speed of light is invariable. This is an attempt to clarify what Einstein wrote and show how experiments routinely confirm that the speed of light is variable. Key words: Speed of Light; Time; Time Dilation; Relativity; Einstein. I. Measuring the speed of light. The fact that the speed of light is variable is demonstrated almost every day. No matter where you measure the speed of light, if you measure it correctly, you will get a result of 299,792,458 meters per second. Does this mean that the speed of light is the same everywhere? No. It means the speed of light per second is the same everywhere. And, according to Einstein’s Theories of Special and General Relativity, the length of a second can be different almost everywhere. That means that if you measure the speed of light to be 299,792,458 meters per second in one location, and if you also measure it to be 299,792,458 meters per second in another location, if the length of a second is different at those two locations, then the speed of light is also different. -

030-125-501 at & Tco Standard Issue 4, February 1979 BUILDING MASTER CLOCKS PRECISE TIME SETTING

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 030-125-501 AT & TCo Standard Issue 4, February 1979 BUILDING MASTER CLOCKS PRECISE TIME SETTING CONTENTS PAGE 2.02 Compare the master clock daily with one of the following references: 1. GENERAL 2. METHOD Operating Company precise time announcement 1. GENERAL machine 1.01 This section covers the method of setting Boston 617 637-1234 Eastern Time all building time reference sources to precise time. Newark 201 936-8181 Eastern Time 1.02 This section is being reissued to change the -+New York 212 936-1616 Eastern Time +- reference telephone number for the precise time announcement machine in Chicago and New Wash., D.C. 202 844-1212 Eastern Time York. Revision arrows are used to indicate the change. This reissue does not affect the Equipment -+ Chicago 312 936-3636 Central Time +- Test List. Detroit 313 472-1212 Eastern Time 1.03 All building time reference sources, such as master clocks and customer call timing devices, U.S. Bureau of Standards must be accurate at all times. Boulder, 303 499-7111 Greenwich 2. METHOD Colo. Mean Time 2.01 Designate one electric clock as a building master clock. Choose a clock with a sweep second hand and preferably one that is not affected by office routine emergency power transfers. Affix Note: Allowance must be made if your local a tag or plastic tape to the master clock stating: time zone differs from the above time zones. Choose a time reference geographically close Caution: Reset per Section 030-125-501. to your office. NOTICE Not for use or disclosure outside the Bell System except under written agreement Printed in U.S.A. -

Time and Frequency from Electrical Power Lines

Time and frequency from electrical power lines Jonathan E. Hardis, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Blair Fonville and Demetrios Matsakis, U.S. Naval Observatory (USNO) BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Jonathan Hardis is a Senior Scientific Advisor within the Physical Measurement Laboratory at NIST. Among his current responsibilities, he serves as a liaison on positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) issues. Previously, he worked in the NIST laboratories developing photometric measurement and consensus standards. Dr. Hardis received a Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Chicago and an S.B. in Physics from MIT. Email: [email protected] Blair Fonville is a Senior Electrical Engineer for Time Services at the U.S. Naval Observatory. He received his M.S. degree in Electrical Engineering from The University of Alabama in 2003. His work at the observatory has involved the characterization of noise processes and precision measurement of phase delays through communication systems equipment, such as the Two-Way Satellite Time and Frequency Transfer system and the Global Positioning System (GPS). Email: [email protected] Dr. Demetrios Matsakis is Chief Scientist for Time Services at the U.S. Naval Observatory (USNO). He received his undergraduate degree in Physics from MIT. His Ph.D. was from U.C. Berkeley, and his thesis, under Charles Townes, involved building masers and using them for molecular radio astronomy and interferometry. Hired at the USNO in 1979, he measured Earth rotation and orientation using Connected Element Interferometry and Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). Beginning in the early 1990s, he started working on atomic clocks and in 1997 was appointed Head of the USNO’s Time Service Department. -

Impacts of Power Grid Frequency Deviation on Time Error of Synchronous Electric Clock and Worldwide Power System Practices on Time Error Correction

energies Article Impacts of Power Grid Frequency Deviation on Time Error of Synchronous Electric Clock and Worldwide Power System Practices on Time Error Correction Yao Zhang 1,*, Wenxuan Yao 1, Shutang You 1 ID , Wenpeng Yu 1, Ling Wu 1, Yi Cui 1 and Yilu Liu 1,2 1 Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA; [email protected] (W.Y.); [email protected] (S.Y.); [email protected] (W.Y.); [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (Y.C.); [email protected] (Y.L.) 2 Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37830, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-865-566-4173 Received: 7 July 2017; Accepted: 25 August 2017; Published: 29 August 2017 Abstract: Synchronous electric clocks utilize power grid frequency as their timing reference. Power grid frequency deviation away from its nominal value results in synchronous electric clocks running fast or running slow (also known as the time error). In this article, statistical analysis on time error of synchronous electric clocks around the world is firstly presented using the power grid frequency measurements recorded by the wide-area frequency monitoring network FNET/GridEye. Then, the time error correction (TEC) process provided by electric utilities is analyzed and the worldwide TEC practice is investigated. Eventually, regions of the world where electric utilities provide TEC service are differentiated from those without TEC services. Analytical results demonstrate that the average time error of synchronous electric clocks in North America seems to be less than five seconds, and it has not changed very much over the past few years. -

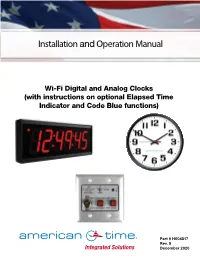

Installation and Operation Manual

Installation and Operation Manual Wi-Fi Digital and Analog Clocks (with instructions on optional Elapsed Time Indicator and Code Blue functions) Part # H004817 Rev. 9 December 2020 Safety Precautions Wi-Fi Installation Manual The Wi-Fi clock(s) should be installed in a secure location protected from: – Physical damage – Water, including condensation – Direct sunlight – Operation by untrained personnel Operation of this product in a manner inconsistent with the instructions in the manual may result in damage to the product and will void the warranty. ifications Spec stallation In Button Button Operation figuration Con ming Clock ming Ho Update Firmware y Defaults y Restore Factor American Time leshooting 140 3rd Street South, PO Box 707 Dassel, MN 55325-0707 Troub Phone: 800-328-8996 Fax: 800-789-1882 american-time.com Appendix 2 © American Time Wi-Fi Installation Manual Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................4 Specifications ............................................................................................................................................................5-7 Installation ............................................................................................................................................................... 8-11 Battery Analog Clocks .............................................................................................................................................8 -

Battle's Clock and Watchmakers

1 BATTLE’S CLOCK AND WATCHMAKERS Early History It has been claimed that Battle was a centre for clock and watch making. Was this the case or did Battle only have typical numbers of clock and watchmakers for a town of its size? A sample analysis of census records for 1851-1911 may provide some indication as to whether this assertion is based on fact. The chart below compares numbers of clock and watchmakers recorded in Battle and Rye, similar Sussex towns, with those to be found in Prescot, a town in the North West known for its clock and watch manufacture in the nineteenth century, being home to the Lancashire Watch Company from 1889. CENSUS BATTLE, Sussex RYE, Sussex PRESCOT, Lancashire YEAR Population No of Population No of Population No of Clock/watch Clock/watch Clock/watch Makers makers makers 1851 6,310 3 6,701 3 12,762 173 1861 5,494 1 6,353 3 12,377 159 1871 5,729 0 6,456 0 13,197 2 1881 5,405 1 6,658 0 15,056 5 1891 6,791 3 6,225 4 19,698 72 1901 6,339 2 6,097 8 16,922 0 1911 7,935 1 6,421 2 24,817 0 Note: Population figures: www.populationspast.org Numbers of clock/watch makers: Census records at www.findmypast.co.uk . Numbers reflect those found using search terms “clockmaker”; “Clock maker”; “watchmaker”; “watch maker”. Certainly census records do not show particularly large numbers of clock and watchmakers were present in Battle when compared to Rye – numbers in both towns seem roughly comparable, although it should be noted that the figures are dependant on search engine results, which may or may not be entirely accurate. -

The Course of Hermann Aron's

MAX-PLANCK-INST I T U T F Ü R W I SSENSCHAFTSGESCH I CHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2009 PREPRINT 370 Shaul Katzir From academic physics to invention and industry: the course of Hermann Aron’s (1845–1913) career Shaul Katzir From academic physics to invention and industry: the course of Hermann Aron’s (1845-1913) career Hermann Aron had an unusual career for a German physicist of the Imperial era. He was an academic lecturer of physics, an inventor, a founder and the manager of a company for electric devices, which employed more than 1,000 employees. Born in 1845 to a modest provincial Jewish family, Aron went through leading schools of the German educational system, received a doctorate in physics and in 1876 the venia legendi - teaching privilege, with which he became a Privatdozent (lecturer) at Berlin university. However, rather than becoming a university professor - the desired goal of this career track - he turned to technology and then industry with the invention of an electricity meter and the foundation of a successful company for its development and manufacture in 1883. By 1897 he owned four sister companies in Berlin, Paris, London, and Vienna-Budapest and manufacturing factories in these cities as well as in Silesia. While in the twentieth century such a career trajectory of a university teacher was not the common case, it was even less so in the late nineteenth century in physics; in many respects it was unique. Aron’s was not the case of a newly qualified doctor hired by industry. -

Electric Time Company, Inc. Exterior Clock Catalog

TOWER CLOCKS www.electrictime.com TM Designing Time TOWERCLOCKS www.electrictime.com ABOUT US Electric Time Company has Electric Time has a complete metal finishing been in continuous operation department - offering line & circle graining since the early 1900’s. We are and polishing, on almost any metal. Our an offshoot of Telechron, the paint finishes are applied in environmentally first self-starting synchronous controlled chambers and have been tested electric clock company. by a National Testing Lab for UV stability, Incorporated in the state of abrasion and corrosion resistance. Massachusetts, USA, in 1928, Products are assembled by our skilled we have grown to a firm that technicians, inspected by our quality has thousands of tower clock department and then shipped in engineered and street clock installations crates to your project location. on every continent. 1950 Factory Our current 50,000 square foot (4,645 square meter) facility allows us the space and resources to design, manufacture and support our products. Standard and custom tower and street clocks are designed by our full time engineering department using state of the art 3D modeling software. We make our own clock movements and properly design them to fit in the enclosure or surrounding structure. If the clock is lighted, we make sure there are no shadows Waldorf Astoria - Clock in Assembly - Orlando, Florida, USA and the clock is evenly lighted with the correct color temperature. In the case of clock hands and As required by electrical codes, by OSHA structures, we perform FEA analysis (finite element and by most insurance companies, our analysis) on the design to be certain they will stand products are listed for up to wind and environmental conditions. -

Vintage Watches, Clocks and Timepieces for the Russell Dimartino Estate

09/29/21 04:10:42 Vintage Watches, Clocks and Timepieces for the Russell DiMartino Estate Auction Opens: Mon, Mar 23 2:00pm CT Auction Closes: Fri, Apr 24 2:00pm CT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 La Reforma Havana Cigars 5¢ Clock 0031 7 Ladies Wrist Watches 0002 German Cuckoo Clock with weights 0032 Mickey mouse wrist watch 0003 Antique Cylindre 10 Rubis Pocket Watch Silver 0033 Ring Watch #955 0034 7 Wrist Watches 0004 Vintage Elgin Ladies Wrist watch gold band 0035 Waltham 21 Jewell Wrist Watch 0005 Dutch metal electric clock 0036 3 Men’s Wrist Watches 0006 Lord Elgin Vintage Wrist Watch 0037 Hamilton Mans Wrist Watch 0007 John Deere model G pocket watch 0038 Tweety Wrist Watch 0008 Ladies EJ Bracelet Wrist Watch 0039 2 Ladies Wrist Watches 0009 Illinois watch company Keystone 14k Gold 0040 Bulova Wrist Watch filled case 0041 Arnex Train Pocket Watch 0010 35 Day Centurion Mantle Clock 0042 Details Sportsman’s Pocket Watch with chain 0011 German Cuckoo Clock working 0043 Rivera Pocketwatch with chain 0012 1890-1900 A.W. Co. Waltham Pocket Watch 0044 Chinese Pocket Watch with Chain 0013 Arnex Time Co. Elk Deer Pocket Watch 0045 Hunters Pocket Watch with chain 0014 Disney Mickey Mouse wrist watch in canister case 0046 Misc Lot of 7 Watches 0015 1890’s Waltham Pocket watch 0047 Box of Wrist Watches 0016 Elgin Pocket Watch Fahys Montauk Gold Case 0048 Cherub desk clock 0017 Elgin Ladies Pocket Watch Philadelphia Case 0049 Mikasa lead crystal desk clock 0018 14 Wrist watches 0050 Swiss Made Burcherer watch in original box 0019 Philadelphia