Senza Titolo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Liberating the Politics of Jesus: Renewing Peace Theology through the Wisdom of Women. Edited by Elizabeth Soto Albrecht and Darryl W. Stephens. London: T & T Clark. 2020. $ 30.95. Liberating the Politics of Jesus: Renewing Peace Theology through the Wisdom of Women centers the voices of women and brings together perspectives from educators, administrators, and practitioners alike. This collection of vibrant, sensitive, and thoughtful reflections advances Anabaptist-Mennonite peace theology in several important and liberatory ways. As co-editor Darryl Stephens observes in the introduction, “The exclusion of women’s experiences and voices from Anabaptist peace theology has impoverished this tradition, resulting in a distorted understanding of the politics of Jesus and collusion with abuse” (3). The volume offers a helpful corrective to this historical inattention and significantly advances a constructive and holistic peace theology that promises to reshape future scholarly and ecclesial directions in important ways. The book’s title does not shy away from explicitly naming “women” as the marginalized demographic to which it will attend. However, this attention is neither overly narrow nor exclusive. Indeed, several of the essays (especially in the first three parts of the book) engage with intersectional identities related to race, sexuality, and nationality, among others. In this way, the collection attends broadly to the many ways in which peace theology is articulated and actualized. This collection of essays is divided into four parts: “Retrieval, Remembering, and Re-envisioning,” “Living the Politics of Jesus in Context,” “Salvation, Redemption, and Witness,” and “Responding to and Learning from John Howard Yoder’s Sexual Violence.” The order of these sections is important. -

Manitoba Book Awards 2021 Les Prix Du Livre Du Manitoba 2021

Manitoba Book Awards 2021 Les Prix du livre du Manitoba 2021 Manitoba Book Awards / Les Prix du livre du Manitoba 2021 Winners List Alexander Kennedy Isbister Award for Non-Fiction / Prix Alexander-Kennedy-Isbister pour les études et essais Sponsor: Manitoba Arts Council Winner - Black Water: Family, Legacy, and Blood Memory by David A. Robertson, published by HarperCollins Nominees For The W: A Look Back at the 2019 Grey Cup Championship Season by Ed Tait, edited by Rhéanne Marcoux, published by The Winnipeg Football Club Peculiar Lessons: How Nature and the Material World Shaped a Prairie Childhood by Lois Braun, published by Great Plains Publications Reinventing Bankruptcy Law: A History of the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act by Virginia Torrie, published by University of Toronto Press Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award / Prix littéraire Carol-Shields de la ville de Winnipeg Sponsor: Winnipeg Arts Council, with funding from the City of Winnipeg Winner - Black Water: Family, Legacy, and Blood Memory by David A. Robertson, published by HarperCollins Nominees Dispelling the Clouds: A Desperate Social Experiment by Wilma Derksen, published by Amity Publishers From the Roots Up: Surviving the City, Vol. 2 by Tasha Spillett, illustrations by Natasha Donovan, published by HighWater Press Harley’s Bootstraps by Lois C. Henderson, published by Friesen Press TreeTalk by Ariel Gordon, with illustrations by Natalie Baird, published by At Bay Press Vignettes from My Life by Tannis M. Richardson, published by Heartland Associates Chris Johnson Award for Best Play by a Manitoba Playwright / Prix Chris-Johnson pour la meilleure pièce par un dramaturge manitobain Sponsor: The Manitoba Association of Playwrights (MAP) Winner - Dragonfly by Lara Rae, published by J. -

Annual Reports 2019

600 Shaftesbury Blvd., Winnipeg, MB R3P 0M4 1310 Taylor Ave., Winnipeg, MB R3M 3Z6 Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society Council Meeting and Annual General Meeting Saturday, March 14, 2020 10:00 a.m. - 12:00 noon Altona Senior Centre Altona, Manitoba Agenda Advisory Council Meeting 1.Welcome 2. Minutes of March 16, 2019 Council Meeting held at the Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach, Manitoba 3. Reports of affiliated organizations: 3.1. Mennonite Heritage Village 3.2. Plett Foundation 3.3 Mennonite Heritage Archives 3.4 The Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren (Centre for MB Studies) 3.5 Heritage Posting 3.6 NeuBergthal Heritage Foundation 3.7 Bergthal School 3.8 Mennonite Heritage Archives 3.9 Peace Exhibit Committee 3.10 History Seekers 3.11 Altona Archives 3.12 Ad-hoc Media Committee 3.13 Genealogy Committee 3.14 Winkler Museum 3.15 History Seekers other 4. Nominations to the MMHS board 5. Adjournment Coffee and dainties will be available AGENDA MMHS AGM 1. Welcome 2. Minutes of the March 16, 2019 annual general meeting held at the Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach, Manitoba 3. Reports from membership committees 3.1. EastMenn WestMenn MMHS Board Finance Other 3.2. Acceptance of reports 4. Resolutions from Treasurer’s report - Bert Friesen 5. Nominations and elections to the MMHS board. 6. Discussion of issues raised by the advisory council upcoming celebrations, commemorations a) Jeremy Wiebe b) Royden Loewen c) Other? 7. Future and direction of MMHS MMHS website update What do we expect from this site? What could it do for the members and others 8. -

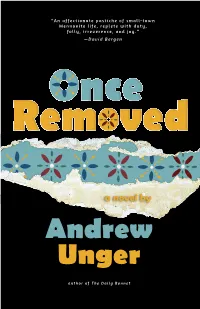

Andrew Unger

“An affectionate pastiche of small-town Mennonite life, replete with duty, folly, irreverence, and joy.” — David Bergen nce Rem ved a novel by Andrew Unger author of The Daily Bonnet Once Removed Once Removed A novel by Andrew Unger TURNSTONE PRESS Once Removed copyright © Andrew Unger 2020 Turnstone Press Artspace Building 206-100 Arthur Street Winnipeg, MB R3B 1H3 Canada www.TurnstonePress.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical—without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request to photocopy any part of this book shall be directed in writing to Access Copyright, Toronto. Turnstone Press gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Arts Council, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, and the Province of Manitoba through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Book Publisher Marketing Assistance Program. Cover: Mennonite floor pattern courtesy Margruite Krahn. Klien Stow (small room), Neuhorst, MB. circa 1880s. Printed and bound in Canada. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Once removed / a novel by Andrew Unger. Names: Unger, Andrew, 1979- author. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200235133 | Canadiana (ebook) 2020023532X | ISBN 9780888017093 (softcover) | ISBN 9780888017109 (EPUB) | ISBN 9780888017116 (Kindle) | ISBN 9780888017123 (PDF) Classification: LCC PS8641.N44 O53 2020 | DDC C813/.6—dc23 for Erin and for the historians, writers, and preservers of memory The following words—every jot and tittle—are a work of fiction, or as my ancestors would say, this book “is complete and utter dommheit.” As such, it would be a foolhardy and futile endeavour to scour these pages for allusions to real peo- ple, places, or events—even the history referenced herein is treated fictionally. -

Bert Friesen Reflects on the History of MMHS and His Involvement the Current Manitoba Arnold Dyck (1889-1970)

Heritage Posting February 2021 1 No. 98 February 2021 Bert Friesen Reflects on the History of MMHS and His Involvement The current Manitoba Arnold Dyck (1889-1970). This was chosen, in part, to Mennonite Historical Society reflect the origins of the group before they separated. The was formed in 1980. A project selected was rooted in the Steinbach community. Manitoba Mennonite My first assignment was to be on the committee that Historical Society (MMHS) oversaw this project. For a young person beginning my had been formed in the late involvement with the writing community, this was 1950s by a group of people challenging. The committee members included Al Reimer from the Steinbach area. (1927-2015), Elisabeth Peters (1915-2011), Harry Loewen Their intent was to collect (1930-2015), George K. Epp (1924-1997), and Victor and preserve artifacts Doerksen (1934-2017), a formidable group to join in the reflecting Mennonite history early 1980s. The project was completed by the end of that in Manitoba since the 1870s. decade and was the beginning of my involvement with By the late 1970s another MMHS. group evolved from the Over the years the society has completed many other Steinbach initiative. This projects besides publications. Local history workshops group wanted to record and were heavily attended in local venues throughout southern publish the history of Manitoba. I recall meetings in Rhineland, Neubergthal, Mennonites in Manitoba. The Steinbach, and Winkler, among others. For many years two groups separated to form these were organized by Adolf Ens and his local history the Mennonite Heritage group. They were intended not only to bring local Village and the Manitoba Bert Friesen, Former enthusiasts together to share a knowledge base, but also Mennonite Historical Society. -

LPG Litdistco Catalogue Fall 2021

Dear Booksellers, Librarians, and Friends of the LPG, Thank you for your on-going support of Canadian independent literature and the publishers that make up the Literary Press Group. We’re looking forward to getting together again to celebrate books as a community. Here are a few updates about our Sales Collective as we head into the second half of 2021: • We are pleased to have long-time LPG member, DC Books, join the LPG Sales Collective. We are also welcoming new member, Renaissance Press of Gatineau, QC, as of June 1, 2021. • Please note that Insomniac Press is no longer represented through the LPG’s Sales Collective. • Please note that no Fall titles were announced for Bluemoon Publishers, DC Books or Stonehouse Publishing. Happy Reading, Tan Light Sales Manager ___________________ The Literary Press Group of Canada 234 Eglinton Ave. E, Suite 401 Toronto, ON M4P 1K5 e: [email protected] p: 416.483.1321 x4 1 LPG Sales Collective Fall 2021 LitDistCo Clients Table of Contents 4 Beach Blonde by John Reynolds 5 Frame by Frame: An Animator's Journey by Co Hoedeman 6 Miraculous Sickness by ky Perraun 7 Coming to Canada by Starkie Mak 8 Gibbous Moon by Dennis Cooley, Michael Matthews 9 Green Parrots in my Garden: Poems from the Arab Middle East by Jane Ross 10 Papillons sur le toit de ma patrie by Sanaz Safari, Alice Anugraham 11 Beyond the Terrazzo Veranda by Morra Norman 12 Breaking Words: Literary Confessions by George Melnyk 13 You have been Referred: My Life in Applied Anthropology by Michael Robinson 14 Enormous Hill, The by Judd Palmer, -

KICKSTARTING PEACE #MUSEUMATHOME Agreement #40033605Agreement MAY 2013 1 PUBLISHED by Mennonite Heritage Village (Canada) Inc

THE VILLAGE VoiceVOLUME 8 NO. 2 • OCTOBER 2020 KICKSTARTING PEACE #MUSEUMATHOME Agreement #40033605Agreement www.mhv.ca MAY 2013 1 PUBLISHED BY Mennonite Heritage Village (Canada) Inc. EXECUTIVE EDITOR Gary Dyck EDITOR KEYWORD: INNOVATION Patrick Friesen BY GARY DYCK, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTORS Gary Dyck Evelyn Friesen Jo-Ann Friesen Everywhere you look at the Mennonite Heritage Village (MHV) Andrea Klassen there is innovation. The housebarns, the windmill, the blacksmith Kara Suderman shop, the printery were all great innovations that served their Abby Toews community well. We still have a lot to learn from the ingeniousness Beth Peters of our foreparents. Raelyn Dick This year our exhibit is celebrating Mennonite Central Committee’s PRINTED BY (MCC) 100 year anniversary. MCC is one of the most innovative Derksen Printers groups in the world. They empowered people like George Klassen DESIGNED BY to make a water pump that could add a second growing season Chez Koop for subsistence farmers in Bangladesh. They developed the Food Grains Bank, which mobilized farmers to plant a portion of their CHARITY NUMBER field for the world’s poor. You can see that pump, see beautiful 10363-393-RR0001 panels and almost touch some artefacts from their history in our AGREEMENT NUMBER Gehard Ens Gallery. 40033605 With COVID-19 comes more need for innovation and at the MHV HOURS we have developed a new way to do life in the village. We did * October - April not host Pioneer Days this year, but every other Saturday we had Gary Dyck Tuesday - Saturday: 9 a.m. - 5 p.m. ‘Demonstration Days’. -

New Hymnal Will Be 'Part of the Fabric of Our Lives'

November 9, 2020 Volume 24 Number 23 New hymnal will be ‘part of the fabric of our lives’ pg. 4 INSIDE Feast of metaphors served at ‘Table talk’ conference 14 Friendships that go ‘a little deeper’ 17 Focus on Books & Resources 20-29 PM40063104 R09613 2 Canadian Mennonite November 9, 2020 editorial articles have addressed personal spiritu- ality, peace, justice, service, Mennonite Good conversations identity, pastoral ministry, the Bible and more. Virginia A. Hostetler This magazine takes inspiration from Executive Editor Hebrews 10 for building up the church: “Let us hold fast to the confession of our flurry of online of conversation. hope without wavering, for he who has comments on a As we at CM try to foster dialogue, we promised is faithful. And let us consider A recent sexual don’t always get things right. Sometimes how to provoke one another to love and misconduct story, an we miss bringing potential partners good deeds . encouraging one another email from a reader into the conversation, or we allow the . .” (Hebrews 10:23-25). Our guiding despairing of having meaningful discourse to get off track. For that, we values include seeking and speaking the dialogue through letters to the maga- apologize and we resolve to do better. truth in love; opening hearts and minds zine, and my congregation’s first online What does good conversation look to discern God’s will; and maintain- business meeting—these got me like? Think of a time you’ve spent chat- ing strong relationships and mutual pondering how we, in the church ting with friends, maybe sipping a hot accountability. -

MH Jun 2021 Magazine.Indd

VOLUME 47, NO. 2 – June 2021 Mennonite Historian A PUBLICATION OF THE MENNONITE HERITAGE ARCHIVES and THE CENTRE FOR MB STUDIES IN CANADA The Friedrichsthal village seal (bottom left) has survived primarily in Teilungs Kontrakt ledgers (estate settlement agreements) like this one. In the presence of the estate heirs, the surviving spouse, the guardians, the trustees, and the representatives of the village administration or sometimes the Waisenamt Vorsteher (director/administrator), the stipulations of the estate settlement agreement were read, witnessed, signed, and stamped with the village seal. MMG stands for Mariupoler Mennoniten Gemeinde, the regional name for the five villages in the Bergthal Colony in Ukraine. Siegel des Dorfs Amte Friedrichsthal means “Seal of the village office of Friedrichsthal.” The above text is the certification paragraph at the end of an estate agreement dated 17 October 1870 and signed by Dorfs-Schulz (mayor) Daniel Blatz, Beisitzer (assistant) Peter Friesen, and Beisitzer Heinrich Dyck. The story of Friedrichsthal, the last Bergthal Colony village, starts on page 2. Photo credit: Ernest N. Braun. Contents Friedrichsthal: Last Village of the Historical Commission Publishes Film and Book Reviews: Bergthal Colony: Part 1 of 2 ............. 2 College History ................................ 7 Otto’s Passion ................................. 15 Unehelich: Mennonite Genealogy and The Search for the Mennonite Once Removed ................................ 16 Illegitimate Births: Part 1 of 3 .......... 3 Centennial Monument in MHA update ........................................... 6 Zaporozhzhia, Ukraine ................... 14 Friedrichsthal: Last Village of refugees have left their home countries, Mariupol[er] Mennonite Colony, but, in usually under duress, but the Bergthal Mennonite circles and later in hindsight, the Bergthal Colony: Part 1 of 2 Colony is still a singularly important it was referred to as the Bergthal Colony by Ernest N. -

Theodidaktos Taught by God Journal for EMC Theology and Education Volume 3 Number 2 September 2008

Theodidaktos Taught by God Journal for EMC theology and education Volume 3 Number 2 September 2008 journeys Editorial Sins of the Corporate Church There are no books entitled Mennonite Theology However, what has transpired in this era of the in the manner of Millard J. Erickson’s Christian Church on earth is something like Augustine’s Theology. If there were, none would contain a perception. What we have today is the Corporate Tsection on our teaching of the Visible and Invisible Church and the True Church, neither of which is Church. That’s because we don’t believe in such a invisible per se. distinction. However, in recent days I have come to Consider that the Corporate Church hires and fi res the conclusion that we may be practicing a behaviour its staff. Consider that at membership meetings the in the Church that is not unlike this peculiar belief. only requirement that one speak up on an issue and Some time in the fourth century theologians vote on it is that you are a member. began referring to the Visible Church. By this they Consider that the Corporate Church is concerned meant the typical members of the local church. These about fi nances, policy and public relations at times were the people you could see attending church and more than the gospel. The Corporate Church is fi lled serving in its various functions. with members, but not necessarily genuine believers, I believe the Invisible Church terminology found for at times we fi nd members acting in their self- its roots in Augustine’s language. -

A Time to Laugh and a Time to Speak

A time to laugh and a time to speak A homily on Ecclesiastes 3:1–8 Andrew Unger In this most famous passage of Ecclesiastes, Solomon (or was it The Byrds?) tells us “there is a time for everything.” There is a time, he says, to weep, to search, to scatter stones, to dance even (although not for Menno- nites apparently), and even a time to laugh. Sometimes I wonder, though, if we as Mennonites have abandoned the laughter as eagerly as we seem to have left out the dancing. Given a certain lens, this passage in Ecclesiastes Ecclesiastes could be could be read as if Solomon is present- read as if Solomon ing dichotomies—situations that never is presenting dichot- cross paths—as if the time to weep and omies—situations the time to laugh cannot ever coincide, that never cross as if times of speaking and staying silent paths—as if the time are fixed rather than fluid. I think this to weep and the reading of the passage is unfortunate, time to laugh can- but common, especially when it comes not ever coincide, as to humor. We (I don’t just mean Men- if times of speaking nonites here) tend to think of the time and staying silent to weep and the time to laugh as very far are fixed rather apart. We often put humor in its own than fluid. tightly constricted box in terms of con- text and content. People will say things like “now is not the time” or “that isn’t funny” or “too soon.” And in these dark times we’re living in now? Well now, certainly, isn’t the time to laugh, some might say. -

Harvesting Manoomin at 'Shooniversity'

May 13, 2019 Volume 23 Number 10 Harvesting manoomin at ‘Shooniversity’ Reflection at the close of the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Team, pg. 12 INSIDE When it’s hard to go to church 4 The gift of ecumenism 11 Breaking through the screen 18 PM40063104 R09613 2 Canadian Mennonite May 13, 2019 editorial fear. / I will hold my hand out to you, / Holding out the Christ-light speak the peace you long to hear.” Virginia A. Hostetler In the today’s feature “When it’s hard Executive Editor to go to church” (page 4), former pastor Donita Wiebe-Neufeld considers how a congregation might walk alongside e can all tough times. In Sunday sharing times, a people dealing with mental illness and have good woman spoke openly about her ongoing other hard life issues. In “Breaking “Wmental struggle with an eating disorder. A through the screen” (page 18), parents health. It is about hav- couple talked about their family and educators are reminded that ing a sense of purpose, member’s schizophrenia and the students’ time with technology can have strong relationships, feeling connected challenges it had for them. A recovering negative effects on their mental and to our communities, knowing who we alcoholic told of how he was using his social health. A sponsored content story are, coping with stress and enjoying past addiction experiences to minister (not available online) tells the story of life,” says a statement by the Canadian to others. As congregants listened and someone who experiences a strong Mental Health Association. learned about each other’s vulnerabil- connection between meaningful Statistics indicate that each year 6.7 ities, we were able to offer prayers, employment and mental well-being.