Versions and Visions of the Alhambra in the Nineteenth Century Ottoman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MJMES Volume VIII

Volume VIII 2005-2006 McGill Journal of Middle East Studies Revue d’études du Moyen-Orient de McGill MCGILL JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST STUDIES LA REVUE D’ÉTUDES DU MOYEN- ORIENT DE MCGILL A publication of the McGill Middle East Studies Students’ Association Volume VIII, 2005-2006 ISSN 1206-0712 Cover photo by Torie Partridge Copyright © 2006 by the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies A note from the editors: The Mandate of the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is to demonstrate the dynamic variety and depth of scholarship present within the McGill student community. Staff and contributors come from both the Graduate and Undergraduate Faculties and have backgrounds ranging from Middle East and Islamic Studies to Economics and Political Science. As in previous issues, we have attempted to bring this multifaceted approach to bear on matters pertinent to the region. *** The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is registered with the National Library of Canada (ISSN 1206-0712). We have regularized the subscription rates as follows: $15.00 Canadian per issue (subject to availability), plus $3.00 Canadian for international shipping. *** Please address all inquiries, comments, and subscription requests to: The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies c/o MESSA Stephen Leacock Building, Room 414 855 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 2T7 Editors-in-chief Aliza Landes Ariana Markowitz Layout Editor Ariana Markowitz Financial Managers Morrissa Golden Avigail Shai Editorial Board Kristian Chartier Laura Etheredge Tamar Gefen Morrissa Golden -

The Armenian Robert L

JULY 26, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXV, NO. 2, Issue 4345 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Armenia Inaugurates AREAL Linear Christians Flee Mosul en Masse Accelerator BAGHDAD (AP) — The message played array of other Sunni militants captured the a mobile number just in case we are offend - YEREVAN (Public Radio of Armenia) — The over loudspeakers gave the Christians of city on June 10 — the opening move in the ed by anybody,” Sahir Yahya, a Christian Advanced Research Electron Accelerator Iraq’s second-largest city until midday insurgents’ blitz across northern and west - and government employee from Mosul, said Laboratory (AREAL) linear accelerator was inau - Saturday to make a choice: convert to ern Iraq. As a religious minority, Christians Saturday. “This changed two days ago. The gurated this week at the Center for Islam, pay a tax or face death. were wary of how they would be treated by Islamic State people revealed their true sav - the Advancement of Natural Discoveries By the time the deadline imposed by the hardline Islamic militants. age nature and intention.” using Light Emission (CANDLE) Synchrotron Islamic State extremist group expired, the Yahya fled with her husband and two Research Institute in Yerevan. vast majority of Christians in Mosul had sons on Friday morning to the town of The modern accelerator is an exceptional and made their decision. They fled. Qaraqoush, where they have found tempo - huge asset, CANDLE’s Executive Director Vasily They clambered into cars — children, par - Most of Mosul’s remaining Christians rary lodging at a monastery. -

Old Buildings, New Views Recent Renovations Around Town Have Uncovered Views of Manhattan That Had Been Hiding in Plain Sight

The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 Old Buildings, New Views Recent renovations around town have uncovered views of Manhattan that had been hiding in plain sight. By Caroline Biggs Impressions: 43,264,806 While New York City’s skyline is ever changing, some recent construction and additions to historic buildings across the city have revealed some formerly hidden, but spectacular, views to the world. These views range from close-up looks at architectural details that previously might have been visible only to a select few, to bird’s-eye views of towers and cupolas that until The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 recently could only be viewed from the street. They provide a novel way to see parts of Manhattan and shine a spotlight on design elements that have largely been hiding in plain sight. The structures include office buildings that have created new residential spaces, like the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan; historic buildings that have had towers added or converted to create luxury housing, like Steinway Hall on West 57th Street and the Waldorf Astoria New York; and brand-new condo towers that allow interesting new vantages of nearby landmarks. “Through the first decades of the 20th century, architects generally had the belief that the entire building should be designed, from sidewalk to summit,” said Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum. “Elaborate ornament was an integral part of both architectural design and the practice of building industry.” In the examples that we share with you below, some of this lofty ornamentation is now available for view thanks to new residential developments that have recently come to market. -

The Ottomans | Court Life

The Ottomans | Court Life ‘The Topkap# Palace was the governmental centre and residence of the imperial family.’ The Topkap# Palace was the governmental centre and residence of the imperial family. It was founded on an area of the Istanbul peninsula which commands views of the Golden Horn on one side, and the Bosphorus Strait and the Sea of Marmara, on the other. It is a complex of buildings in three parts (birun, enderun and harem) situated within large gardens. The birun is between the first gate, Bab-# Hümayun (Imperial Gate), and the third gate, Babü’s-Saade (Gate of Felicity). The first courtyard accommodated the service buildings, the imperial mint, military barracks, ministries and other governmental offices. The second courtyard was called Alay Meydan# and housed the Divan-# Hümayun – also called ‘Under the Dome’ – the treasury, the kitchens, stables and the entrance to the harem. Ceremonies, for instance enthronement, the royal hearing in case of emergencies known as Alay Divan# (Assembly on Foot) and the celebration of feasts, were made in front of the Gate of Felicity. The sultan’s throne was also placed near the Gate; and the Holy Flag (Sancak-# #erif), the very symbol of the Ottoman Sultan as Caliph, was raised here when it was taken out of the Pavilion of the Holy Mantel on ceremonial occasions. Name: Topkap# Palace Dynasty: Construction began in hegira 9th century / AD 15th century, during the reign of Sultan Mehmed II (his second reign: AH 855–86 / AD 1451–81); the last addition was made under Sultan Abdülmecid ['Abd al-Majid] (r. -

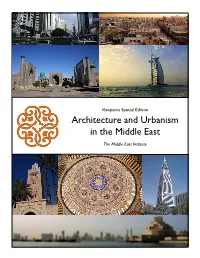

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Thesis Final Copy V11

“VIENS A LA MAISON" MOROCCAN HOSPITALITY, A CONTEMPORARY VIEW by Anita Schwartz A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Teaching Art Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2011 "VIENS A LA MAlSO " MOROCCAN HOSPITALITY, A CONTEMPORARY VIEW by Anita Schwartz This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Angela Dieosola, Department of Visual Arts and Art History, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty ofthc Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Teaching Art. SUPERVISORY COMMIITEE: • ~~ Angela Dicosola, M.F.A. Thesis Advisor 13nw..Le~ Bonnie Seeman, M.F.A. !lu.oa.twJ4..,;" ffi.wrv Susannah Louise Brown, Ph.D. Linda Johnson, M.F.A. Chair, Department of Visual Arts and Art History .-dJh; -ZLQ_~ Manjunath Pendakur, Ph.D. Dean, Dorothy F. Schmidt College ofArts & Letters 4"jz.v" 'ZP// Date Dean. Graduate Collcj;Ze ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Professor John McCoy, Dr. Susannah Louise Brown, Professor Bonnie Seeman, and a special thanks to my committee chair, Professor Angela Dicosola. Your tireless support and wise counsel was invaluable in the realization of this thesis documentation. Thank you for your guidance, inspiration, motivation, support, and friendship throughout this process. To Karen Feller, Dr. Stephen E. Thompson, Helena Levine and my colleagues at Donna Klein Jewish Academy High School for providing support, encouragement and for always inspiring me to be the best art teacher I could be. -

Echoes of Paradise: the Garden and Flora in Islamic Art | Flora and Arabesques: Visions of Eternity and Divine Unity

Echoes of Paradise: the Garden and Flora in Islamic Art | Flora and Arabesques: Visions of Eternity and Divine Unity ‘When flowers are not depicted naturalistically they are often used in fantastic arrangements.’ When flowers are not depicted naturalistically in Islamic art, they are often used in more or less fantastic arrangements intended to enhance the surface of a building or an artefact to their best advantage. Such floral compositions are often so intricate that they completely distract the eye from the physical characteristics of the object they decorate or, indeed, obscure them. Buildings and artefacts may appear as if draped with carved, painted or applied floral arrangements. Primarily decorative, such floral schemes still offer spiritual minds the opportunity to contemplate the eternal complexity of the Universe, which emanates and culminates in its Creator, Allah. Name: Great Mosque and Hospital of Divri#i Dynasty: Hegira 626/ AD 1228–9 Mengücekli Emirate Details: Divri#i, Sivas, Turkey Justification: The entire façade of this imposing structure is enhanced with fantastic floral designs, suggesting that a higher world can be found beyond its gate. Name: Chest from Palencia Cathedral Dynasty: Hegira 441 / AD 1049–50 Taifa kingdom of Banu Dhu'l-Nun Details: National Archaeological Museum Madrid, Spain Justification: The intricate floral openwork seen on this casket suggests a delicate layer of lace rather than solid ivory plaques on a wooden core. Name: Qur'an Dynasty: Hegira Safar 1259 / AD March 1843 Ottoman Details: Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey Justification: The Word of Allah in the Qur'an is enclosed by a floral frame, the design of which is inspired by European Baroque and Rococo patterns.. -

Manifiesto De La Alhambra English

Fernando Chueca Goitia and others The Alhambra Manifesto (1953) Translated by Jacob Moore Word Count: 2,171 Source: Manifiesto de la Alhambra (Madrid, Dirección General de Arquitectura, 1953). Republished as El Manifiesto de la Alhambra: 50 años después: el monumento y la arquitectura contemporánea, ed. Ángel Isac, (Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Consejería de Cultura, Junta de Andalucía : Tf Editores, 2006) 356-375. We, the signers of this Manifesto, do not want to be pure iconoclasts, for we are already too weary of such abrupt and arbitrary turns. So people will say: “Why the need for a Manifesto, a term which, almost by definition, implies a text that is dogmatic and revolutionary, one that breaks from the past, a public declaration of a new credo?” Simply put, because reality, whose unequivocal signs leave no room for doubt, is showing us that the ultimate traditionalist posture, which architecture adopted after the war of Liberation, can already no longer be sustained and its tenets are beginning to fall apart. […] Today the moment of historical resurrections has passed. There is no use denying it; just as one cannot deny the existence of the Renaissance in its time or that of the nineteenth century archaeological revivals. The arts have tired of hackneyed academic models and of cold, lifeless copies, and seek new avenues of expression that, though lacking the perfection of those that are known, are more radical and authentic. But one must also not forget that the peculiar conditions implicit in all that is Spanish require that, within the global historical movement, we move forward, we would not say with a certain prudence, but yes, adjusting realities in our own way. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

The Berber Identity: a Double Helix of Islam and War by Alvin Okoreeh

The Berber Identity: A Double Helix of Islam and War By Alvin Okoreeh Mezquita de Córdoba, Interior. Muslim Spain is characterized by a myriad of sophisticated and complex dynamics that invariably draw from a foundation rooted in an ethnically diverse populace made up of Arabs, Berbers, muwalladun, Mozarebs, Jews, and Christians. According to most scholars, the overriding theme for this period in the Iberian Peninsula is an unprecedented level of tolerance. The actual level of tolerance experienced by its inhabitants is debatable and relative to time, however, commensurate with the idea of tolerance is the premise that each of the aforementioned groups was able to leave a distinct mark on the era of Muslim dominance in Spain. The Arabs, with longstanding ties to supremacy in Damascus and Baghdad exercised authority as the conqueror and imbued al-Andalus with culture and learning until the fall of the caliphate in 1031. The Berbers were at times allies with the Arabs and Christians, were often enemies with everyone on the Iberian Peninsula, and in the times of the taifas, Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, were the rulers of al-Andalus. The muwalladun, subjugated by Arab perceptions of a dubious conversion to Islam, were mired in compulsory ineptitude under the pretense that their conversion to Islam would yield a more prosperous life. The Mozarebs and Jews, referred to as “people of the book,” experienced a wide spectrum of societal conditions ranging from prosperity to withering persecution. This paper will argue that the Berbers, by virtue of cultural assimilation and an identity forged by militant aggressiveness and religious zealotry, were the most influential ethno-religious group in Muslim Spain from the time of the initial Muslim conquest of Spain by Berber-led Umayyad forces to the last vestige of Muslim dominance in Spain during the time of the Almohads. -

Moorish Architectural Syntax and the Reference to Nature: a Case Study of Algiers

Eco-Architecture V 541 Moorish architectural syntax and the reference to nature: a case study of Algiers L. Chebaiki-Adli & N. Chabbi-Chemrouk Laboratoire architecture et environnement LAE, Ecole polytechnique d’architecture et d’urbanisme, Algeria Abstract The analogy to nature in architectural conception refers to anatomy and logical structures, and helps to ease and facilitate knowledge related to buildings. Indeed, several centuries ago, since Eugène Violet-le-Duc and its relationship to the botanic, to Phillip Steadman and its biological analogy, many studies have already facilitated the understanding and apprehension of many complex systems, about buildings in the world. Besides these morphological and structural aspects, environmental preoccupations are now imposing themselves as new norms and values and reintroducing the quest for traditional and vernacular know-how as an alternative to liveable and sustainable settlements. In Algiers, the exploration of traditional buildings, and Moorish architecture, which date from the 16th century, interested many researchers who tried to elucidate their social and spatial laws of coherence. An excellent equilibrium was in effect, set up, by a subtle union between local culture and environmental adaptability. It is in continuation of André Ravéreau’s architectonics’ studies that this paper will make an analytical study of a specific landscape, that of a ‘Fahs’, a traditional palatine residence situated at the extra-mural of the medieval historical town. This ‘Fahs’ constitutes an excellent example of equilibrated composition between architecture and nature. The objective of this study being the identification of the subtle conjugation between space syntax and many elements of nature, such as air, water and green spaces/gardens. -

Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture

REPORTS 21. Materials and methods are available as supporting 27. N. Panagia et al., Astrophys. J. 459, L17 (1996). Supporting Online Material material on Science Online. 28. The authors would like to thank L. Nelson for providing www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/315/5815/1103/DC1 22. A. Heger, N. Langer, Astron. Astrophys. 334, 210 (1998). access to the Bishop/Sherbrooke Beowulf cluster (Elix3) Materials and Methods 23. A. P. Crotts, S. R. Heathcote, Nature 350, 683 (1991). which was used to perform the interacting winds SOM Text 24. J. Xu, A. Crotts, W. Kunkel, Astrophys. J. 451, 806 (1995). calculations. The binary merger calculations were Tables S1 and S2 25. B. Sugerman, A. Crotts, W. Kunkel, S. Heathcote, performed on the UK Astrophysical Fluids Facility. References S. Lawrence, Astrophys. J. 627, 888 (2005). T.M. acknowledges support from the Research Training Movies S1 and S2 26. N. Soker, Astrophys. J., in press; preprint available online Network “Gamma-Ray Bursts: An Enigma and a Tool” 16 October 2006; accepted 15 January 2007 (http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/astro-ph/0610655) during part of this work. 10.1126/science.1136351 be drawn using the direct strapwork method Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline (Fig. 1, A to D). However, an alternative geometric construction can generate the same pattern (Fig. 1E, right). At the intersections Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture between all pairs of line segments not within a 10/3 star, bisecting the larger 108° angle yields 1 2 Peter J. Lu * and Paul J. Steinhardt line segments (dotted red in the figure) that, when extended until they intersect, form three distinct The conventional view holds that girih (geometric star-and-polygon, or strapwork) patterns in polygons: the decagon decorated with a 10/3 star medieval Islamic architecture were conceived by their designers as a network of zigzagging lines, line pattern, an elongated hexagon decorated where the lines were drafted directly with a straightedge and a compass.