140Anniversary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

Evelyn De Morgan Y La Hermandad Prerrafaelita

Trabajo Fin de Grado Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan y la Hermandad Prerrafaelita Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan and the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood. Autor/es Irene Zapatero Gasco Director/es Concepción Lomba Serrano Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Curso 2018/2019 LUX IN TENEBRIS: EVELYN DE MORGAN Y LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA IRENE ZAPATERO GASCO DIRECTORA: CONCEPCIÓN LOMBA SERRANO HISTORIA DEL ARTE, 2019 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN - JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TRABAJO…………………………………....1 - OBJETIVOS…………………………………………………………....2 - METODOLOGÍA……………………………………………………....2 - ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN………………………………………....3 - AGRADECIMIENTOS………………………………………………...5 LA ÉPOCA VICTORIANA - CONTEXTO HISTORICO…………………………………………….6 - EL PAPEL QUE DESEMPEÑABA LA MUJER EN LA SOCIEDAD…………………………………………………………….7 LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA…………………………………...10 EVELYN DE MORGAN - TRAYECTORIA E IDEOLOGÍA ARTÍSTICA……………………...13 - EL IDEAL ICÓNICO RECREADO…………………..……………....15 - LA REPRESENTACIÓN DE LA MUJER EN SU PRODUCCIÓN ARTÍSTICA...........................................................................................16 I. EL MUNDO ESPIRITUAL…………………………………...17 II. HEROÍNAS SAGRADAS…………………………………….21 III. ANTIBELICISTAS…………………………………………....24 CONCLUSIONES…………...……………………………………………….26 BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y WEBGRAFÍA…………………………………………28 ANEXOS….……………………………………………………………..........32 - REPERTORIOGRÁFICO…………………………………………….46 INTRODUCCIÓN JUSTIFIACIÓN DEL TRABAJO Centrado en la obra de la pintora Evelyn De Morgan (1855, Londres) nuestro trabajo pretende revisar su producción artística contextualizándola -

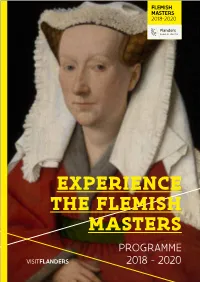

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II From1952 To2017

الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II from1952 to2017 Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in (LC) Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms. Leila BASSAID Mrs. Souad HAMIDI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Assia BENTAYEB Chairperson Mrs. Souad HAMIDI Supervisor Dr. Yahia ZEGHOUDI examiner Academic Year: 2016-2017 Dedication First of all thanks to Allah the most Merciful. Every challenging work needs self efforts as well as guidance of older especially those who were very close to our heart, my humble efforts and dedications to my sweet and loving parents: Ali and Soumya whose affection, love and prayers have made me able to get such success and honor, and their words of encouragement, support and push for tenacity ring in my ears. My two lovely sisters Manar and Ibtihel have never left my side and are very special, without forgetting my dearest Grandparents for their prayers, my aunts and my uncle. I also dedicate this dissertation to my many friends and colleagues who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all they have done, especially my closest friends Wassila Boudouaya, for helping me, Fatima Zahra Benarbia, Aisha Derouich, Fatima Bentahar and many other friends who kept supporting and encouraging me in everything for the many hours of proofreading. I Acknowledgements Today is the day that writing this note of thanks is the finishing touch on my dissertation. -

Jerry Uelsmann by Sarah J

e CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY • UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER 15 JANUARY 1982 DEAN BROWN Contents The Dean Brown Archive 3 by James L. Enyeart An Appreciation 5 by Carol Brown Dean Brown: An Overview by Susan E. Ruff 6 Dean Brown: 11 A Black-and-White Portfolio Dean Brown: 25 A Color Portfolio Exhibitions of the Center 45 1975-1981 by Nancy D. Solomon Acquisitions Highlight: 51 Jerry Uelsmann by Sarah J. Moore Acquisitions: 54 July-December 1980 compiled by Sharon Denton The Archive, Research Series, is a continuation of the research publication entitled Cmter for Creative Photography; there is no break in the consecutive numbering of issues. The A ,chive makes available previously unpublished or unique material from the collections in the Archives of the Center for Creative Photography. Subscription and renewal rate: $20 (USA), S30 (foreign), for four issues. Some back issues are available. Orders and inquiries should be addressed to: Subscriptions Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona 843 E. University Blvd. Tucson, Arizona 85719 Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona Copyright © 1982 Arizona Board of Regents All Rights Reserved Photographs by Dean Brown Copyright ©1982 by Carol Brown Designed by Nancy Solomon Griffo Alphatype by Morneau Typographers Laser-Scanned Color Separations by American Color Printed by Prisma Graphic Bound by Roswell Bookbinding The Archive, Research Series, of the Center for Creative Photography is supported in part by Polaroid Corporation. Plate 31 was reproduced in Cactus Country, a volume in the Time Life Book series-The American Wilderness. Plates 30, 34, and 37 were reproduced in Wild Alaska from the same series. -

Scenes from the Passion of Christ: the Agony in the Garden, The

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Andrea Vanni Andrea di Vanni Sienese, c. 1330 - 1413 Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the Descent into Limbo [entire triptych] 1380s tempera on panel overall: 56.9 × 116.4 × 3.4 cm (22 3/8 × 45 13/16 × 1 5/16 in.) Inscription: middle panel, lower center on original frame, some of the letters restored: ANDREAS UANNIS / DE SENIS / ME PINXIT (Andreas di Vanni of Siena painted me); middle panel, above the cross, in gold bordered by red rectangle: INRI; middle panel, on red flag, in gold: SPQR; right panel, in black paint on the scroll held by God the Father: Destruxit quidam mortes inferni / et subvertit potentias diaboli; right panel, in black paint on the scroll held by Saint John the Baptist: ECCE.ANGIUS[AGNUS]. (Behold the Lamb) Corcoran Collection (William A. Clark Collection) 2014.79.711.a-c ENTRY This highly detailed triptych by the Sienese painter Andrea di Vanni is a recent addition to the National Gallery of Art collection. One of the most prominent works acquired from the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the altarpiece consists of three panels depicting stories from the Passion of Christ. Attached by modern hinges, the two lateral panels can be folded over the central painting to protect it and facilitate transportation. When opened, the triptych’s panels represent, from left to right, Christ’s Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, the Crucifixion, and Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the 1 Descent into Limbo [entire triptych] National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries the Descent into Limbo. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abell, Sam. Stay this Moment : The Photographs of Sam Abell. Rochester, N.Y.; Charlottesville, Va: Professional Photography Division, Eastman Kodak Co; Thomasson-Grant, 1990. Print. Aberth, Susan L., and Leonora Carrington. Leonora Carrington : Surrealism, Alchemy and Art. Aldershot, Hampshire; Burlington, VT: Lord Humphries; Ashgate, 2004. Print. Abram, David. Becoming Animal : An Earthly Cosmology. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 2010. Print. ---. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996. Print. Using descriptive personal stories of interaction with nature David Abram introduces the reader to phenomenology. This philosophy rejects the separation of the human mind by Descartes and believes all observation is participatory. Abram brings Merleau-Ponty’s theory that the human body is the true subject of experience through examples, often as his outings in nature. I related to this work for I believe humans aren’t superior, that we are interconnected and part of the chain of life with other creatures. I never knew my beliefs were part of an existing philosophy. It is through full sensory interaction with the earth that we realize we must do more to save it. Abram’s book is a call to all humans to join in this activity, reawakening our senses to the rest of the world. Allmer, Patricia, and Manchester City Art Gallery. Angels of Anarchy : Women Artists and Surrealism. Munich ; New York: Prestel, 2009. Print. Anderson, Adrian. Living a Spiritual Year: Seasonal Festivals in Northern and Southern Hemispheres : An Esoteric Study. Rudolph Steiner Press, 1993. Print. Avedon, Richard, et al. Evidence, 1944-1994. 1st ed. New York: Random House, Eastman Kodak Professional Imaging in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994. -

Teachers' Resource

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE JOURNEYS IN ART AND AMBITION CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION: JOURNEYS IN ART AND AMBITION 2: THE YOUNG DÜRER: CURATOR’S QUESTIONS 3: DÜRER’S LINES OF ENQUIRY 4: ARTISTIC EXCHANGE IN RENAISSANCE EUROPE 5: CROSSING CONTINENTS, CONVERGING CULTURES 6: LINES TRAVELLED AND DRAWN: A CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE PERSPECTIVE 7: ‘DÜRER ALS MODERNER EUROPÄER’ GERMAN LANGUAGE ACTIVITY 8: GLOSSARY 9: TEACHING RESOURCE CD Teachers’ Resource JOURNEYS IN ART AND AMBITION Compiled and produced by Niccola Shearman and Sarah Green Design by WJD SUGGESTED CURRICULUM LINKS FOR EACH ESSAY ARE MARKED IN ORANGE TERMS REFERRED TO IN THE GLOSSARY ARE MARKED IN PURPLE To book a visit to the gallery or to discuss any of the education projects at The Courtauld Gallery please contact: e: [email protected] t: 0207 848 1058 WELCOME The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. I hope the material will prove to be both useful and inspiring. Henrietta Hine Head of Public Programmes The Courtauld Institute of Art This resource offers teachers and their students an opportunity to explore the wealth of The Courtauld Gallery’s permanent collection by expanding on a key idea drawn from our exhibition programme. Taking inspiration from the exhibition The Young Durer: Drawing the Figure (17 October 2013 – 12 January 2014), the focus of this teachers’ resource is ‘Journeys in Art and Ambition’. -

Worksheet the Kingts Speech

worksheet the king’s speech Taking a Class to See The King’s Speech “Le Discours d’un Roi” TEACHER’S PAGE INTRODUCTION As a fact-based, historical film set in London in the 1930s, The King’s Speech is an educational film in the best sense of the term. It will bring the period alive for your pupils, giving them a sense of the fashion, cars, lifestyle – and even the weather – in London at the time. In addition, it will provide a good explanation of the Abdication Crisis, and the background to how the current Queen wound up ascending to the throne, following her grandfather, uncle and father (Kings George V, Edward VIII and George VI, respectively). MATEriAls NEEDED Trailers: www.momentumpictures.co.uk/ A copy of the Student Worksheets per pupil. Pupils should (pass the cursor over the video then click on the 4- have them before going to see the film, to get the most out arrow symbol on the right to get the trailer full screen) and of the film and be prepared to do the activities afterwards. www.lediscoursdunroi.com (click on the "videos" thumb- Access to a computer room or a projector connected to nail, then choose VOSTFR). a computer to work with the sites listed on the right. Or Audio of the real King George VI giving the speech: an OHP, if you want to make a transparency of the pictures www.awesomestories.com/assets/george-vi-sep-3-1939 provided here, which can be downloaded at a higher reso- Audio of Princess Elizabeth giving a speech during the war lution from: www.lediscoursdunroi.com/presse/). -

NATION, NOSTALGIA and MASCULINITY: CLINTON/SPIELBERG/HANKS by Molly Diane Brown B.A. English, University of Oregon, 1995 M.A. En

NATION, NOSTALGIA AND MASCULINITY: CLINTON/SPIELBERG/HANKS by Molly Diane Brown B.A. English, University of Oregon, 1995 M.A. English, Portland State University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND FILM STUDIES This dissertation was presented by Molly Diane Brown It was defended on May 14, 2009 and approved by Marcia Landy, PhD, Distinguished Professor, Film Studies Adam Lowenstein, PhD, Associate Professor, Film Studies Brent Malin, PhD, Assistant Professor, Communication Dissertation Advisor: Lucy Fischer, PhD, Distinguished Professor, Film Studies ii Copyright © by Molly Diane Brown 2009 iii NATION, NOSTALGIA AND MASCULINITY: CLINTON/SPIELBERG/HANKS Molly Diane Brown, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 This dissertation focuses on masculinity in discourses of nostalgia and nation in popular films and texts of the late 20th century’s millennial period—the “Bill Clinton years,” from 1992-2001. As the 1990s progressed, masculinity crises and millennial anxieties intersected with an increasing fixation on nostalgic popular histories of World War II. The representative masculine figures proffered in Steven Spielberg films and Tom Hanks roles had critical relationships to cultural crises surrounding race, reproduction and sexuality. Nostalgic narratives emerged as way to fortify the American nation-state and resolve its social problems. The WWII cultural trend, through the specter of tributes to a dying generation, used nostalgic texts and images to create imaginary American landscapes that centered as much on contemporary masculinity and the political and social perspective of the Boomer generation as it did on the prior one.