Dorothy Thompson: Withstanding the Storm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender, Knowledge and Power in Radical Culture

POETESSES AND POLITICIANS: GENDER, KNOWLEDGE AND POWER IN RADICAL CULTURE, 1830-1870 HELEN ROGERS submitted for the degree of D.Phil University of York History Department and Centre for Women's Studies September 1994 CONTENTS PAGE Acknowledgements Abstract Introduction - Poetesses and Politicians: Rethinking Women and Radicalism, 1830-1870 1 I Poetesses and Politicians 2 II Rethinking Women and Radicalism, 1830-1870 12 Chapter One - The Politics of Knowledge in Radical Culture, 1790-1834 25 I Reason, Virtue and Knowledge: Political and Moral Science in the 1790s 27 II "Union is Knowledge": Political and Moral Economy in the 1820s and 1830s 37 Chapter Two - "The Prayer, The Passion and the Reason" of Eliza Sharples: Freethought, Women's Rights and Republicanism, 1832-1852 51 I The Making of a Republican, 1827-1832 i The Conversion 54 ii "Moral Marriage": A Philosophical Partnership? 59 iii The Forbidden Fruit of Knowledge 64 II "The Lady of the Rotunda" 72 III "Proper Help Meets for Men": Eliza Sharpies and Female Association in Metropolitan Radical Culture, in the Early 1830s 81 IV "The Poverty of Philosophy": Marriage, Widowhood, and Politics, 1833-1852 94 Chapter Three - "A Thinking and Strictly Moral People": Education and Citizenship in the Chartist Movement 102 I Chartist Debates on Education as Politics 111 II "Sound Political Wisdom from the Lips of Women": Chartist Women's Political Education 120 III Chartist Women and Moral and Physical Force 130 IV Conclusion "What Power has Woman...?" 138 Chapter Four - "The Good Are Not Always -

Owatonna, Minnesota

The O-Pinion Owatonna, Minnesota Meeting each Monday 12:10 p.m. – Owatonna Country Club Four way test: 1) Is it the truth?; 2) Is it fair to all concerned?; 3) Will it build good will and better friendships?; 4) Will it be beneficial to all concerned? OFFICERS DAVE EFFERTZ President JOHN MUELLERLEILE President-Elect RENEE LOWERY Secretary CINDY SCHEID, Treasurer DAVE ALLARD Past President FACEBOOK PAGE: www.facebook.com/RotaryClubofOwatonna BOARD OF DIRECTORS John Muellerleile Pat Greenwood Holly Hull Cindy Scheid Doug Parr Jennifer Dunn Foster Earl Anderson Dan McIntosh Keith Hiller Dave Effertz Renee Lowery Penny Vizina Todd Hale Dave Allard Lois Nelson Chris Herzog AREA MEETING PLACES & TIMES Austin Mondays Noon Holiday Inn Winona Wednesdays Noon Westfield Golf Club Janesville Mondays 6 PM St. Ann’s Parish Northfield Thursdays Noon Northfield Golf Club Owatonna Early Edition Tuesdays 7 AM Owatonna Fire Hall Great Rochester Thursdays Noon Kahler Grand Hotel Rochester Risers Tuesdays 7 AM Hilton Garden Inn Waseca Thursdays Noon Miller/Armstrong Red Wing Tuesdays Noon St. James Hotel Albert Lea Fridays Noon Ramada Inn Faribault Wednesdays Noon Bernie’s Grill North Mankato Fridays Noon Best Western Hotel Mankato Wednesdays Noon Old Main Village UPCOMING PROGRAMS Date Program February 13 Robin Miller: Humor in Dealing with Trauma February 20 The New Koda Living Community: Terry Schneider February 27 Business Meeting: OFF SITE AT HISTORY CENTER FOR TOUR March 5 Owatonna Police Chief Keith Hiller March 12 Craig Wahl: Visiting Angels Elder Services: MEET AT HISTORY CNTR March 19 Tanya Paley: Safe and Drug Free Coalition: MEET AT HISTORY CENTR. -

American University Library

BLOCKADE BEFORE BREAD: ALLIED RELIEF FOR NAZI EUROPE, 1939-1945 B y Meredith Hindley Submitted to the Faculty of the College for Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In H istory Chair: Richard Dr-Breitman Anna K. Nelson Weslev^K. Wdrk Dean of^ie CoHegeMArtsand Sciences D ate 2007 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3273596 Copyright 2007 by Hindley, Meredith All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3273596 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © COPYRIGHT by Meredith Hindley 2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLOCKADE BEFORE BREAD: ALLIED RELIEF FOR NAZI EUROPE, 1939-1945 BY Meredith Hindley ABSTRACT This study provides the first analysis of Allied relief policy for Nazi-occupied territories— and by extension Allied humanitarian policy— during the Second World War. -

The Byline of Europe: an Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-8-2017 The Byline of Europe: An Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941 Kerry J. Garvey Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Garvey, Kerry J., "The Byline of Europe: An Examination of Foreign Correspondents' Reporting from 1930 to 1941" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 671. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/671 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BYLINE OF EUROPE: AN EXAMINATION OF FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTING FROM 1930 TO 1941 Kerry J. Garvey 133 Pages This thesis focuses on two of the largest foreign correspondents’ networks the one of the Chicago Tribune and New York Times- in prewar Europe and especially in Germany, thus providing a wider perspective on the foreign correspondents’ role in news reporting and, more importantly, how their reporting appeared in the published newspaper. It provides a new, broader perspective on how foreign news reporting portrayed European events to the American public. It describes the correspondents’ role in publishing articles over three time periods- 1930 to 1933, 1933-1939, and 1939 to 1941. Reporting and consequently the published paper depended on the correspondents’ ingenuity in the relationship with the foreign government(s); their cultural knowledge; and their gender. -

Making and Circulating the News in an Illiberal Age

Making and Circulating the News in an Illiberal Age Nancy F. Cott Author’s note: Rather than aiming to keep up with extraordinarily fast-changing news from and about the White House, I have kept this essay essentially as I delivered it during the early days of Donald J. Trump’s presidency. Te 2017 Organization of American Historians conference theme of “circulation” had the virtue of capaciousness, evoking many diferent potential applications, tangible and intangible, natural and constructed, operating at various scales. Roads around a city, ideas around the world, blood through the body, rumors through a community—all of these circulate. So does news. Circulation is intrinsic to news. Tat is my topic tonight because we have been living through a transformation in the ways that news is made and promulgated. Digital platforms for breaking news, commentary, and scandal have multiplied—and their potential to propagate access to varied sources of information and misinformation is obvious. Te essential network aspect of the “web” means that any in- formation easily reproduces itself and generates links that connect it to similar or related information. Te making and the promulgation of news are tied together perhaps more tightly than ever before, in that whatever becomes most intensely circulated and repli- cated through instantaneous media becomes the most pressing “news.” Tus circulation makes the news, more than simply transmitting it. We now face a proliferation—I might say a plague—of news sources and modes of circulation. Tis multiplication and fractionalization leads away from the creation of “common knowledge” and toward division of the populace into “niche” publics whose knowledge-worlds intentionally seek replenishment from sources that reinforce accus- tomed attitudes and partisan leanings. -

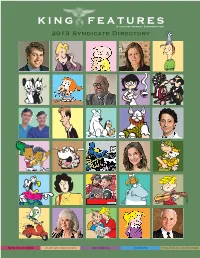

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

A Study of the Women's Suffrage Movement in Nineteenth-Century English Periodical Literature

PRINT AND PROTEST: A STUDY OF THE WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH PERIODICAL LITERATURE Bonnie Ann Schmidt B.A., University College of the Fraser Valley, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREEE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History 43 Bonnie Ann Schmidt 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fa11 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Bonnie Ann Schmidt Degree: Master of Arts Title: Print and Protest: A Study of the Women's Suffrage Movement in Nineteenth-Century English Periodical Literature Examining Committee: Dr. Ian Dyck Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of History Dr. Mary Lynn Stewart Supervisor Professor of Women's Studies Dr. Betty A. Schellenberg External Examiner Associate Professor of English Date Defended: NOV.s/15 SIMON FRASER UN~VER~~brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

The Jews of Europe Before the Second World War

The Jews of Europe Before the Second World War American Historical Association Annual Meeting New Orleans, January 5, 2013 • THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER THE JEWS BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR • THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER The Norman Lear Center is a nonpartisan research and public policy center that studies the social, political, economic and cultural impact of entertainment on the world. The Lear Center translates its findings into action through testimony, journalism, strategic research and innovative public outreach campaigns. On campus, from its base in the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism, the Lear Center builds bridges between schools and disciplines whose faculty study aspects of entertainment, media and culture. Beyond campus, it bridges the gap between the entertainment industry and academia, and between them and the public. Through scholarship and research; through its conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and practice in the field. For more information, please visit: www.learcenter.org. HISTORIANS, JOURNALISTS & THE CHALLENGES OF GETTING IT RIGHT Historians, Journalists and the Challenges of Getting It Right is a partnership of the Lear Center, USC Annenberg’s Center for Communication Leadership & Policy and the American Historical Association”s National History Center. It begins with the premise that both professions, historians and journalists, are in the business of finding and assessing evidence; of analyzing events; and of narrating events. Both are storytellers. Both could enhance their work by learning from each other, by establishing networks that connect them, by sharing expertise and by sharing practical knowledge about media and methods. -

The Letters of Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Fall 1988 Dear Kit, Dear Skinny: The Letters of Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White William L. Howard Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Howard, William L. "Dear Kit, Dear Skinny: The Letters of Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White." The Courier 23.2 (1988): 23-44. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 2, FALL 1988 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII NUMBER TWO FALL 1988 Dorothy Thompson: Withstanding the Storm By Michael J. Kirkhom, Associate Professor of Journalism, 3 New York University Dear Kit, Dear Skinny: The Letters of Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke,White By William L. Howard, Assistant Professor of English, 23 Chicago State University Ted Key, Creator of "Hazel" By George L. Beiswinger, author and free,lance writer, 45 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Five Renaissance Chronicles in Leopold von Ranke's Library By Raymond Paul Schrodt, Ambrose Swasey Library, 57 Colgate Rochester Divinity School The Punctator's World: A Discursion By Gwen G. Robinson, Editor, Syracuse University 73 Library Associates Courier News of the Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 105 Dear Kit, Dear Skinny: The Letters of Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke,White BY WILLIAM L. HOWARD Complementing the substantial Margaret Bourke'White Papers at the George Arents Research Library at Syracuse University is a smaller collection of Erskine Caldwell material from the years when he and Bourke,White were lovers and, subsequently, during 1939-42, hus, band and wife. -

Spelman's Political Warriors

SPELMAN Spelman’s Stacey Abrams, C’95 Political Warriors INSIDE Stacey Abrams, C’95, a power Mission in Service politico and quintessential Spelman sister Kiron Skinner, C’81, a one-woman Influencers in strategic-thinking tour de force Advocacy, Celina Stewart, C’2001, a sassy Government and woman getting things done Public Policy THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE | SPRING 2019 | VOL. 130 NO. 1 SPELMAN EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Renita Mathis Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs COPY EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Beverly Melinda James Atlanta, GA 30314 OR http://www.spelmanlane.org/SpelmanMessengerSubmissions GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Submission Deadlines: Fall Issue: Submissions Jan. 1 – May 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER Spring Issue: Submissions June 1 – Dec. 31 Danielle K. Moore ALUMNAE NOTES EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: Jessie Brooks • Education Joyce Davis • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Sharon E. Owens, C’76 • Professional Jane Smith, C’68 Please include the date of the event in your submission. TAKE NOTE! EDITORIAL INTERNS Take Note! is dedicated to the following alumnae Melody Greene, C’2020 achievements: Jana Hobson, C’2019 • Published Angelica Johnson, C’2019 • Appearing in films, television or on stage Tierra McClain, C’2021 • Special awards, recognition and appointments Asia Riley, C’2021 Please include the date of the event in your submission. WRITERS BOOK NOTES Maynard Eaton Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae and faculty authors. Connie Freightman Please submit review copies. Adrienne Harris Tom Kertscher IN MEMORIAM We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive notice Alicia Lurry of the death of a Spelman sister, please contact the Kia Smith, C’2004 Office of Alumnae Affairs at 404-270-5048 or Cynthia Neal Spence, C’78, Ph.D. -

Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 2001 Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library Chad Wheaton Syracuse University Carolyn A. Davis Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wheaton, Chad and Davis, Carolyn A., "Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library" (2001). The Courier. 337. https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/337 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIB RA RY ASS 0 CI ATE S c o URI E R VOLUME XXXIII . 1998-2001 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VO LU ME XXXIII 1998-2001 Franz Leopold Ranke, the Ranke Library at Syracuse, and the Open Future ofScientific History By Siegfried Baur, Post-Doctoral Fellow 7 Thyssen Foundation ofCologne, Germany Baur pays tribute to "the father ofmodern history," whose twenty-ton library crossed the Atlantic in 1888, arriving safely at Syracuse University. Mter describ ing various myths about Ranke, Baur recounts the historian's struggle to devise, in the face ofaccepted fictions about the past, a source-based approach to the study ofhistory. Librarianship in the Twenty-First Century By Patricia M. Battin, Former Vice President and 43 University Librarian, Columbia University Battin urges academic libraries to "imagine the future from a twenty-first cen tury perspective." To flourish in a digital society, libraries must transform them selves, intentionally and continuously, through managing information resources, redefining roles ofinformation professionals, and nourishing future leaders. -

Dorothy Thompson and German Writers in Defense of Democracy by Karina Von Tippelskirch (Review)

Dorothy Thompson and German Writers in Defense of Democracy by Karina von Tippelskirch (review) Paul Michael Lützeler German Studies Review, Volume 43, Number 1, February 2020, pp. 187-189 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/gsr.2020.0020 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/749907 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] Reviews 187 to German studies scholars, his subject also has broad appeal to social and cultural historians of modern Europe. Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Simon Fraser University Dorothy Thompson and German Writers in Defense of Democracy. By Karina von Tippelskirch. Berlin: Peter Lang, 2018. Pp. 299. Paper $50.95. ISBN 978-3631707036. This book, including its brief but instructive introduction by Sigrid Bauschinger, deals with Dorothy Thompson’s (1893–1961) journalistic publications, as well as her correspondence and fragmentary autobiographical writing. She was the most famous and most influential US female journalist of the 1930s and 1940s, and her impressive knowledge of the German language and German and Austrian literature and culture foregrounded the success of her work in Europe. While most newspaper and radio reports are quickly forgotten, Dorothy Thompson’s contributions are still studied by historians, literary scholars, and media specialists. Karina von Tippelskirch’s book is not simply another biography on Thompson, but a study demonstrating Thompson’s impact on US policies regarding