Ielrc.Org/Content/B1302.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Analysis of the Extent to Which the National Land Commission Addresses the Land Question in Kenya

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE EXTENT TO WHICH THE NATIONAL LAND COMMISSION ADDRESSES THE LAND QUESTION IN KENYA. BY ERIC MULEVU G62/75293/2014 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Of Master of Laws (L.L.M) In The University of Nairobi Nairobi, Kenya. Supervisor: PROFESSOR KAMERI -MBOTE ii Declaration of Originality 1. I understand what plagiarism is and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination, or in the award of a degree or publication. Where other people’s work or my own work has been used, this has properly been acknowledged and referenced in accordance with the University of Nairobi’s requirements. 3. I have not sought or used the services of any professional agencies to produce this work. 4. I have not allowed, and shall not allow anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off his/her own work. 5. I understand that any false claim in respect of this work shall result in disciplinary action, in accordance with the University of Nairobi’s plagiarism policy. Name : Patricia Kameri- Mbote Signature…………………………………………………………………………………………... Date…………………………………………………………………………………………….. Name…………………………………………………………………………………………. Signature…………………………………………………………………………………………... Date…………………………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Statutes The Constitution of Kenya 2010. National Land Commission Act, 2012 The Land Act, 2012. Land Registration Act, 2012 Case Laws 1Abdulkadir Khalif vs Principal secretary and Others. Reference no. 479/2017, High Court NLC vs AG & Others, Advisory Opinion. Reference no.2/2014, Supreme Court. NLC vs Ex-Parte Leting Jr. -

Draft Nlc Research Framework

NATIONAL LAND COMMISSION LAND ENVIRONMENT AND RESEARCH COMMITTEE COMMISSION PAPER 6 NATIONAL LAND COMMISSION RESEARCH FRAMEWORK. July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................... 3 DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Preamble .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Vision ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Mission............................................................................................................................ 1 1.4 Research Philosophy ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Scope of the Framework ..................................................................................................... 4 1.6 Purpose of Research Framework ................................................................................ 4 1.7 Objectives of the Research Framework ....................................................................... 4 1.8 Organogram of the Commission ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER -

Kenya's Supreme Court

Kenya’s Supreme Court: Old Wine in New Bottles? By Special Correspondent As the six Supreme Court judges were adjudicating Kenya’s first presidential election petition in March 2013, Justice Kalpana Hasmukhrai Rawal was waiting for a new president to take office and the newly elected National Assembly to convene so that her nomination as Deputy Chief Justice could move forward. The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) had settled on her appointment after interviewing a shortlist of applicants in February 2013. The Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board had earlier found her to be suitable to continue serving as a Court of Appeal judge. Justice Rawal eventually joined the Supreme Court on 3 June 2013. Two years later, Justice Rawal became the second Deputy Chief Justice (after Nancy Baraza, who resigned after she was heavily criticised for abusing her authority by threatening a security guard after the guard demanded to search her at a mall) to be embroiled in controversy. In 2015, Rawal challenged a notice that she retire at the age of 70. Around the same time, the then Chief Justice, Dr Willy Mutunga, would announce that he wanted to retire early so that the next Chief Justice would be appointed well ahead of the next election. In May 2014, Justice Philip Kiptoo Tunoi and High Court judge David Onyancha challenged the JSC’s decision to retire them at the age of 70. They argued that they were entitled to serve until they reached the age of 74 because they had been first appointed judges as under the old constitution. What seemed like a simple question about the retirement age of judges led to an unprecedented breakdown in the collegiate working atmosphere among the Supreme Court judges that had been maintained during the proceedings of the presidential election petition. -

Reflections from Kenya's 2010 Transformative Constitution

Developing Progressive African Jurisprudence: Reflections from Kenya’s 2010 Transformative Constitution 2017 LAMECK GOMA ANNUAL LECTURE Lusaka, Zambia, July 27, 2017 Willy Mutunga1 Preliminary Remarks Chair of SAIPAR Members of the Institute I thank the Southern African Institute for Policy and Research (SAIPAR) for inviting me to give the PROFESSOR LAMECK GOMA ANNUAL LECTURE 2017. The late Professor Goma was a great scholar, the first Zambian Vice-Chancellor of the University of Zambia. He was also a great researcher and a patriotic public servant. 1 Dr. Willy Mutunga is the former Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya and the President of the Supreme Court of Kenya. A major part of my remarks are taken from a speech I gave to Judges and guests of the Kenyan Judiciary on the occasion of the launching the Judiciary Transformation Framework on May 31, 2012. That speech has been published in the Socialist Lawyer: Magazine of the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers. Number 65. 2013,20. The journey of my thoughts since then and now reflected in this Lecture owes a great debt of intellectual, ideological and political gratitude to the following mentors and friends: Professors Jill Ghai, Yash Ghai, Sylvia Tamale, Joel Ngugi, James Gathii, Joe Oloka-Onyango, Issa Shivji, Makau Mutua, Obiora Okafor, Yash Tandon, David Bilchitz, Albie Sachs, Duncan Okello, Roger Van Zwanenberg, and Shermit Lamba. My Law Clerks at the Supreme of Kenya, namely, Atieno Odhiambo, Sam Ngure and Maxwell Miyawa helped with research. The theme of this Lecture is drawn -

2018 ANNUAL MEETING from Imitation to Innovation

2018 ANNUAL MEETING From Imitation to Innovation NOVEMBER 10 – 12, 2018 DOHA, QATAR HOSTED BY INDEX WELCOME ………………………………………………………………………… 3 AGENDA …………………………………………………………………………... 4 GROUP BREAKOUTS …………………………………………………………… 10 GOVERNING BOARD …………………………………………………………… 13 DOCTRINAL STUDY GROUPS ………………………………………………… 14 UNIVERSITIES ATTENDING …………………………………………………… 15 BOARD OF GOVERNORS ATTENDEES ……………………………………... 17 QATAR UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF LAW ATTENDEES …………………. 21 JUDICIAL ATTENDEES …………………………………………………………. 25 ATTENDEES ……………………………………………………………………… 29 SECRETARIAT …………………………………………………………………… 58 SINGAPORE DECLARATION ………………………………………………….. 59 MADRID PROTOCOL ……………………………………………………………. 61 JUDICIAL STANDARDS OF A LEGAL EDUCATION ……………………….. 62 SELF-ASSESSMENT REPORT ………………………………………………… 63 EVALUATION, ASSISTANCE, AND CERTIFICATION PROGRAM ……….. 66 2 WELCOME On behalf of all the members of the International Association of Law Schools Board of Governors, we want to welcome each and every one of you to our 2018 Annual Meeting. This is our eleventh annual meeting where over 115 law teachers from more than 30 countries have gathered together to discuss and formulate new strategies to improve legal education globally. Almost half of our participants are senior law school leaders (deans, vice deans and associate deans). We warmly welcome all the familiar faces from these many years – welcome and thank you for your continued engagement in advancing the cause of improving legal education globally. For those who are new, a special warm welcome from our community. Please meet your colleagues from around the world. We look forward to working with you in this challenging and engaging effort. The IALS is a non-political, non-profit learned society of more than 160 law schools and departments from over 55 countries representing more than 7,500 law faculty members. One of our primary missions is the improvement of law schools and conditions of legal education throughout the world by learning from each other. -

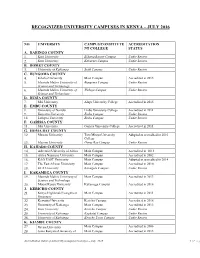

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Special Issue the Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No. 64 NAIROBI, 19th April, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 5381 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 ELECTION PETITIONS, 2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed and sitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC County Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati I.E.B.C Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE, 1/3/2021, Monday

PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE, 1/3/2021, Monday © Prof Ben Sihanya, JSD & JSM (Stanford), LLM (Warwick), LLB (Nairobi), PGD Law (KSL) IP and Constitutional Professor, Public Interest Advocate and Mentor Constitutional Democracy, ©, TM, IP, Education Law, Public Interest Lawyering Commissioner for Oaths, Notary Public, Patent Agent, Author, Public Intellectual & Poet University of Nairobi Law School & Prof Ben Sihanya Advocates & Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering Author: IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Transferring Technology for Sustainable Development (2016; 2020); IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Cases and Materials (forthcoming 2021); Constitutional Democracy, Regulatory and Administrative Law in Kenya and Africa Vols. 1, 2 & 3 (due 2021) [email protected]; [email protected]; url: www.sihanyaprofadvs.co.ke; www.innovativelawyering.com Nairobi; Revised 3/2/2021; 12/2/2021; 1/3/2021 1 PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE 1989 to Monday, March 1, 2021 Prof Ben Sihanya, JSD & JSM (Stanford), LLM (Warwick), LLB (Nairobi), PGD Law (KSL) IP and Constitutional Professor, Public Interest Advocate and Mentor Constitutional Democracy, ©, TM, IP, Education Law, Public Interest Lawyering Commissioner for Oaths, Notary Public, Patent Agent, Author, Public Intellectual & Poet University of Nairobi Law School & Prof Ben Sihanya Advocates & Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering Author: IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Transferring Technology for Sustainable -

Vigilant Civil Society Enforces Implementation of National Land Commission

CASE STUDY Nairobi, Kenya Vigilant civil society enforces PRINCIPAL ORGANISATIONS INVOLVED implementation Kenya Land Alliance (KLA), Land Sector Non State Actors (LSNSA), Ford of National Land Foundation, Kenya Private Sector Alliance LOCATION Nairobi, Kenya Commission This case illustrates how non-state actors collaborated with TIMELINE citizens to compel the Kenyan State to appoint a Land 2012 - 2013 Commission, an institution provided for by the law. The objective of a decentralised and autonomous Land TARGET AUDIENCE Commission was to improve land governance in Kenya and Civil society, policy makers, communities increase the accountability of executives. However, the Kenyan Executive was delaying the creation of this institution. KEYWORDS Diverse and complementary strategies were put in place by Governance, community, mobilisation, non-state actors and communities, which mobilised to ensure advocacy, multi-stakeholder cooperation that the Government complied with a Constitutional provision aimed at improving land governance in Kenya. GOOD PRACTICES towards making land governance more people-centred This case study is part of the ILC’s Database of Good Practices, an initiative that documents and systematises ILC members and partners’ experience in promoting people-centred land governance, as defined in the Antigua Declaration of the ILC Assembly of Members. Further information at www.landcoalition.org/what-we-do This case study supports people-centred land governance as it contributes to: Commitment 1 Respect, protect and strengthen the land rights of women and men living in poverty Commitment 7 Ensure that processes of decision-making over land are inclusive Commitment 8 Ensure transparency and accountability Case description Background issues Kenya has a history of land related conflict. -

Supreme Court Act

LAWS OF KENYA SUPREME COURT ACT NO. 7 OF 2011 Revised Edition 2017 [2011] Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General www.kenyalaw.org [Rev. 2017] No. 7 of 2011 Supreme Court NO. 7 OF 2011 SUPREME COURT ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I – PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. 3. Object of the Act. PART II – ADMINISTRATION OF THE SUPREME COURT 4. Vacancy not to affect jurisdiction. 5. Order of precedence of judges of the Supreme Court. 6. Presiding judge. 7. Procedure if judges absent. 8. Manner of arriving at decisions. 9. Registrar of the Supreme Court. 10. Functions of the Registrar. 11. Revision of decisions of the Registrar. PART III – JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT 12. Determination of disputes arising out of presidential elections. 13. Advisory role. 14. Special jurisdiction. PART IV – APPEALS TO THE SUPREME COURT 15. Appeals to be by leave. 16. Criteria for leave to appeal. 17. Direct appeals only in exceptional circumstances. 18. Reasons for refusal of leave to appeal. 19. Extent of appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. PART V – GENERAL 20. Appeals to proceed by fresh hearing. 21. General powers. 22. Power to remit proceedings. 23. Exercise of powers of the Court. 24. Interlocutory orders and directions by the Court. 25. Judgment of the Court. 26. Delivery of judgment. 27. Decisions of the Court may be enforced by the High Court. 28. Contempt of Court. 29. Seal of the Supreme Court. 30. Representation before the Supreme Court. 31. Rules. 3 [Rev. 2017] No. -

Funded Degree Programmes and Partners Involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21)

Funded degree programmes and partners involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21) Regional universities/networks are participating in the scholarship programme as partner institutions Call for application West and Central Africa: Deadline: February, 10th 2021 West and Central Africa Benin • University of Abomey – Calavi (UAC) Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, Mathematics (Master, PhD) International Chair in Mathematical Physics and Applications (CIPMA), Natural Sciences (Master, PhD) Burkina Faso • International Institute for Water and Environmental Engineering (2iE), Engineering (Master, PhD) Ghana • University for Development Studies (UDS), Department of Public Health, Medicine - Public Health (Master Phil, Master Sc) • University of Ghana, Regional Institute for Population Studies (RIPS), Humanities / Political Science (Master, PhD) West African Center for Crop Improvement (WACCI), University of Ghana, Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Nigeria • University of Ibadan, Subject fields: Fisheries Management and Energy Studies (Master) Network • Centre d 'Etudes Régional pour l'Amélioration de l'Adaptation à la Sécheresse (CERAAS), Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Eastern Africa Call for application Eastern Africa: Deadline: December, 15th 2020 Ethiopia Addis Ababa University - IPSS, Subject field: Global & Area Studies (PhD) • Hawassa University - Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources (WGCF), Agro-Forestry (Master) Kenya • Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), Information Technology (PhD), Mechanical -

14Th September, 2017 TO; the Secretary Judicial Service

14th September, 2017 TO; The Secretary Judicial Service Commission Supreme Court Building NAIROBI Dear Madam, RE: PETITION AGAINST JUSTICE DAVID MARAGA Chief Justice & President of Supreme Court A. COMPLAINTS & FACTS THEREOF 1.0 Violation of Regulation 12 of The Judicial Code of Conduct & Ethics The Chief Justice has invited, encouraged and permitted entry into the core of the Judiciary by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) who are known protagonists of the President and Deputy President and who propagated the prosecution of the President and Deputy President at the International Criminal Court (ICC). These elements have now captured the Judiciary with the intent of procuring a regime change through judicial radicalism. The Chief Justice has, inter alia; a) Invited, facilitated and supported the embedding of technical support and financing by the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) to entities within the Judiciary including the Judicial Training Institute, National Council for Administration of Justice and Judicial Election Committee, with full knowledge that the IDLO organization is associated with the known anti-government partisan protagonists, including Makau Mutua who is a Board Member thereof; with full knowledge that the entity collaborates with local non-state actors that participated in prosecuting the President and Deputy President at the I.C.C; with full knowledge that the entity is further associated with local non-governmental organizations and individuals who petitioned against the election of the President