Management of Persistent Postpartum Pelvic Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peripartum Pubic Symphysis Diastasis—Practical Guidelines

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Peripartum Pubic Symphysis Diastasis—Practical Guidelines Artur Stolarczyk , Piotr St˛epi´nski* , Łukasz Sasinowski, Tomasz Czarnocki, Michał D˛ebi´nski and Bartosz Maci ˛ag Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, Medical University of Warsaw, 02-091 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (Ł.S.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (B.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Optimal development of a fetus is made possible due to a lot of adaptive changes in the woman’s body. Some of the most important modifications occur in the musculoskeletal system. At the time of childbirth, natural widening of the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joints occur. Those changes are often reversible after childbirth. Peripartum pubic symphysis separation is a relatively rare disease and there is no homogeneous approach to treatment. The paper presents the current standards of diagnosis and treatment of pubic diastasis based on orthopedic and gynecological indications. Keywords: pubic symphysis separation; pubic symphysis diastasis; pubic symphysis; pregnancy; PSD 1. Introduction The proper development of a fetus is made possible due to numerous adaptive Citation: Stolarczyk, A.; St˛epi´nski,P.; changes in women’s bodies, including such complicated systems as: endocrine, nervous Sasinowski, Ł.; Czarnocki, T.; and musculoskeletal. With regard to the latter, those changes can be observed particularly D˛ebi´nski,M.; Maci ˛ag,B. Peripartum Pubic Symphysis Diastasis—Practical in osteoarticular and musculo-ligamento-fascial structures. Almost all of those changes Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. -

Pelvic Anatomyanatomy

PelvicPelvic AnatomyAnatomy RobertRobert E.E. Gutman,Gutman, MDMD ObjectivesObjectives UnderstandUnderstand pelvicpelvic anatomyanatomy Organs and structures of the female pelvis Vascular Supply Neurologic supply Pelvic and retroperitoneal contents and spaces Bony structures Connective tissue (fascia, ligaments) Pelvic floor and abdominal musculature DescribeDescribe functionalfunctional anatomyanatomy andand relevantrelevant pathophysiologypathophysiology Pelvic support Urinary continence Fecal continence AbdominalAbdominal WallWall RectusRectus FasciaFascia LayersLayers WhatWhat areare thethe layerslayers ofof thethe rectusrectus fasciafascia AboveAbove thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? BelowBelow thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? MedianMedial umbilicalumbilical fold Lateralligaments umbilical & folds folds BonyBony AnatomyAnatomy andand LigamentsLigaments BonyBony PelvisPelvis TheThe bonybony pelvispelvis isis comprisedcomprised ofof 22 innominateinnominate bones,bones, thethe sacrum,sacrum, andand thethe coccyx.coccyx. WhatWhat 33 piecespieces fusefuse toto makemake thethe InnominateInnominate bone?bone? PubisPubis IschiumIschium IliumIlium ClinicalClinical PelvimetryPelvimetry WhichWhich measurementsmeasurements thatthat cancan bebe mademade onon exam?exam? InletInlet DiagonalDiagonal ConjugateConjugate MidplaneMidplane InterspinousInterspinous diameterdiameter OutletOutlet TransverseTransverse diameterdiameter ((intertuberousintertuberous)) andand APAP diameterdiameter ((symphysissymphysis toto coccyx)coccyx) -

Surgical Management of Chronic Lower Abdominal and Groin Pain In

Surgical Management of Chronic Lower Abdominal and Groin Pain in High-performance Athletes 08/02/2019 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD33D9/FQ5Fz8lUYgSwgVMpoyvWKSXvZI2V7wPePfaqAcGjSNveYeZYww== by https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr from Downloaded William C. Meyers, MD, Anthony Lanfranco, BAS, and Andres Castellanos, MD Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr Address pubalgia, and a similar number of patients who have not Drexel University College of Medicine, Department of Surgery, required surgery. Much of the specific data on these patients Mail Stop 413, 245 North 15th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA. will be documented in that study. We are compelled to E-mail: [email protected] mention one preliminary observation: there are still too Current Sports Medicine Reports 2002, 1:301–305 many patients undergoing incorrect operations! This Current Science Inc. ISSN 1537-890x by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD33D9/FQ5Fz8lUYgSwgVMpoyvWKSXvZI2V7wPePfaqAcGjSNveYeZYww== Copyright © 2002 by Current Science Inc. observation comes from data that show more than 200 patients who, having undergone various unsuccessful opera- tions, did well after a second surgery or other treatments. Formerly, most of the causes and treatments of chronic lower Before outlining our current approach to these types of abdominal and groin pain in high-performance athletes eluded problems, five general comments are necessary. sports medicine specialists. Now we are much better at To begin, athletic pubalgia is but one such diagnosis that identifying and managing the different syndromes. Most of the occurs in high-performance athletes. It should be under- advances are based on empiric evidence, although many stood that there are many other potential diagnoses. The pitfalls remain with respect to diagnosis and management pelvis has a great number of bones, projections, and soft tis- of the various syndromes. -

The Neuroanatomy of Female Pelvic Pain

Chapter 2 The Neuroanatomy of Female Pelvic Pain Frank H. Willard and Mark D. Schuenke Introduction The female pelvis is innervated through primary afferent fi bers that course in nerves related to both the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic pelvis includes the bony pelvis, its ligaments, and its surrounding skeletal muscle of the urogenital and anal triangles, whereas the visceral pelvis includes the endopelvic fascial lining of the levator ani and the organ systems that it surrounds such as the rectum, reproductive organs, and urinary bladder. Uncovering the origin of pelvic pain patterns created by the convergence of these two separate primary afferent fi ber systems – somatic and visceral – on common neuronal circuitry in the sacral and thoracolumbar spinal cord can be a very dif fi cult process. Diagnosing these blended somatovisceral pelvic pain patterns in the female is further complicated by the strong descending signals from the cerebrum and brainstem to the dorsal horn neurons that can signi fi cantly modulate the perception of pain. These descending systems are themselves signi fi cantly in fl uenced by both the physiological (such as hormonal) and psychological (such as emotional) states of the individual further distorting the intensity, quality, and localization of pain from the pelvis. The interpretation of pelvic pain patterns requires a sound knowledge of the innervation of somatic and visceral pelvic structures coupled with an understand- ing of the interactions occurring in the dorsal horn of the lower spinal cord as well as in the brainstem and forebrain. This review will examine the somatic and vis- ceral innervation of the major structures and organ systems in and around the female pelvis. -

Incidence and Risk Factors of Symptomatic Peripartum Diastasis of Pubic Symphysis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Musculoskeletal Disorders http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.2.281 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 281-286 Incidence and Risk Factors of Symptomatic Peripartum Diastasis of Pubic Symphysis Jeong Joon Yoo,1 Yong-Chan Ha,2 This study was undertaken to determine incidence, associated risk factors, and clinical Young-Kyun Lee,1 Joon Seok Hong,3 outcomes of a diastasis of pubic symphysis. Among 4,151 women, who delivered 4,554 Bun-Jung Kang,4 and Kyung-Hoi Koo1 babies at the Department of Obstetrics of Seoul National University Bundang hospital from January 2004 to December 2006, eleven women were diagnosed as having a symptomatic 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, National University College of Medicine, Seoul; 2Department diastasis of pubic symphysis. We estimated the incidence of the diastasis and identified the of Orthopedic Surgery, Chung-Ang University associated risk factors. To evaluate the pain relief and reduction of diastasis we followed up College of Medicine, Seoul; 3Department of the 11 diastatic patients. The incidence of the diastasis was 1/385. Primiparity (P = 0.010) Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National and twin gestation (P = 0.016) appeared as risk factors for diastasis by univairable analysis; University College of Medicine, Seoul; 4Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Gyeongsang National and twin gestation appeared to be the only risk factor (P = 0.006) by logistic analysis. Two University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea patients were operated due to intractable pain; and the remaining nine patients were treated conservatively. The diastatic gap decreased to less than 1.5 cm by 2 to 6 weeks Received: 2 August 2013 after the diagnosis and then remained stationary. -

Chronic Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Girdle Pain and Dysfunction

Chronic Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Girdle Pain and Dysfunction Successfully Holly Jonely, PT, ScD, FAAOMPT1,3 Melinda Avery, PT, DPT1 Managed with a Multimodal and Mehul J. Desai, MD, MPH2,3 Multidisciplinary Approach: A Case Series 1The George Washington University, Department of Health, Human Function and Rehabilitation Sciences, Program in Physical Therapy, Washington, DC 2The George Washington University, School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Department of Anesthesia & Critical Care, Washington, DC 3International Spine, Pain & Performance Center, Washington, DC ABSTRACT PGP, impairments of the SIJ are not lim- Case 2 Background and Purpose: Sacroiliac ited to intraarticular pain and often include A 30-year-old nulliparous female with joint (SIJ) or pelvic girdle pain (PGP) account impairments of the surrounding muscles or a chronic history of right posterior pelvic for 20-40% of all low back pain cases in the connective tissues, as well as, aberrant and pain following an injury as a college athlete United States. Diagnosis and management asymmetrical movement patterns within the participating in crew. She reported slipping of these disorders can be challenging due to region of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex.7 in a boat and falling onto her sacrum. Her limited and conflicting evidence in the lit- These impairments have a negative impact previous conservative management included erature and the varying patient presentation. on the PG’s role in support and load trans- physical therapy that emphasized pelvic The purpose of this case series is to describe fer between the lower extremities and trunk. manipulations, use of a pelvic belt, and stabi- the outcome observed in 3 patients present- This ariabilityv in observed impairments lization exercises. -

Laboratory 8 - Urinary and Reproductive Systems

Laboratory 8 - Urinary and Reproductive Systems Urinary System Please read before starting: It is easy to damage the structures of the reproductive system as you expose structures associated with excretion, so exercise caution as you do this. Please also note that we will have drawings available as well to help you find and identify the structures described below. The major blood vessels serving the kidneys are the Renal renal artery and the renal pyramid vein., which are located deep in the parietal peritoneum. The renal artery is a branch of the dorsal aorta that comes off Renal further caudal than the cranial pelvis mesenteric artery. Dissect the left kidney in situ, dividing it into dorsal and ventral portions by making a frontal section along the outer periphery. Observe the renal cortex renal medulla (next layer in) renal pyramids renal pelvis ureter (see above diagram) The kidneys include a variety of structures including an arterial supply, a venous return, extensive capillary networks around each nephron and then, of course, the filtration and reabsorption apparatus. These structures are primarily composed of nephrons (the basic functional unit of the kidney) and the ducts which carry urine away from the nephron (the collecting ducts and larger ducts eventually draining these into the ureters from each kidney. The renal pyramids contain the extensions of the nephrons into the renal medulla (the Loops of Henle) and the collecting ducts. Urine is eventually emptied into the renal pelvis before leaving the kidneys in the ureters. The ureters leaves the kidneys medially at approximately the midpoint of the organs and then run caudal to the urinary bladder. -

Articulations: Synarthrosis and Amphiarthrosis

Articulations: Synarthrosis and Amphiarthrosis It's common to think of the skeletal system as being made up of only bones, and performing only the function of supporting the body. However, the skeletal system also contains other structures, and performs a variety of functions for the body. While the bones of the skeletal system are fascinating, it is our ability to move segments of the skeleton in relation to one another that allows us to move around. Each connection of bones is called an articulationor a joint. Articulations are classified based on material at the joint and the movement allowed at the joint. Synarthrosis Articulations Immovable articulations are synarthrosis articulations ("syn" means together and "arthrosis" means joint); immovable articulations sounds like a contradiction, but all regions where bones come together are called articulations, so there are articulations that don't move, including in the skull, where bones have fused, and where your teeth meet your jaw. These synarthroses are joined with fibrous connective tissue. Some synarthroses are formed by hyaline cartilage, such as the articulation between the first rib and the sternum (via costal cartilage). This immoveable joint helps stabilize the shoulder girdle and the cartilage can ossify in adults with age. The epiphyseal plate or “growth plate” at the end of long bones is also a synarthrosis until hyaline cartilage ossification is completed around the time of puberty. Amphiarthrosis Articulations There are some articulations which have limited motion called amphiarthrosis articulations. They are held in place with fibrocartilage or fibrous connective tissue. The anterior pelvic girdle joint between pubic bones (pubic symphysis) and the intervertebral joints of the spinal column (discs) are examples of cartilaginous amphiarthroses. -

Low Back Pain Anatomy of the Pubic Symphysis Sacroiliac Joint Articular

Sacroiliac Joint dysfunction, Coccydinia, and Dynamic stability of the lumbo-pelvic region Low back pain altered Pelvic Floor function: is there a link? Stability of inter-segmental lumbar motion is reliant on appropriate control of muscle activation by the central nervous system Delayed recruitment of Increased activity of deep local muscles superficial global muscles -Lumbar multifidus -Transversus abdominus -EO / IO -Pelvic floor -Erector spinae -iliopsoas -biceps femoris Presented by TrA, lower transverse fibres Increase segmental stiffness Compensation due to Dr Barbara Hungerford PhD B.App.Sci (Physio) Internal oblique (OI), deep Co-contract and limit inter-segmental lumbar multifidus & pelvic motion in lumbar spine decreased segmental stability Director : Sydney Spine & Pelvis Centre, Australia floor activate prior to motion : Advanced Manual Therapy Associates (Hodges & Richardson, 1997; Moseley et al, 2002; O’Sullivan et al, 1997) Hides, 94; Hodges & Richardson, 96; Hodges 2003; Radebold 2000 Lumbo-pelvic Stability and optimal load transfer Anatomy of the pubic symphysis Sacroiliac joint articular surface Lumbo-pelvic region is always interacting with * Fibrocartilaginous gravity joint The SIJ is classified as a * interposed by *diarthroidal synovial joint fibrocartilaginous 65% body weight *hyaline articular cartilage transferred across L5/ disc *synovial capsule S1 in standing * most stable joint in pelvis *6 degrees of freedom Pelvis is the stable platform or hub of the skeleton Developmental changes of the SIJ articular Factors -

1 Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall 1

Chapter 1 Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall 1 Orhan E. Arslan 1.1 Introduction The abdominal wall encompasses an area of the body boundedsuperiorlybythexiphoidprocessandcostal arch, and inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, pubic bones and the iliac crest. Epigastrium Visualization, palpation, percussion, and ausculta- Right Left tion of the anterolateral abdominal wall may reveal ab- hypochondriac hypochondriac normalities associated with abdominal organs, such as Transpyloric T12 Plane the liver, spleen, stomach, abdominal aorta, pancreas L1 and appendix, as well as thoracic and pelvic organs. L2 Right L3 Left Visible or palpable deformities such as swelling and Subcostal Lumbar (Lateral) Lumbar (Lateral) scars, pain and tenderness may reflect disease process- Plane L4 L5 es in the abdominal cavity or elsewhere. Pleural irrita- Intertuber- Left tion as a result of pleurisy or dislocation of the ribs may cular Iliac (inguinal) Plane result in pain that radiates to the anterior abdomen. Hypogastrium Pain from a diseased abdominal organ may refer to the Right Umbilical Iliac (inguinal) Region anterolateral abdomen and other parts of the body, e.g., cholecystitis produces pain in the shoulder area as well as the right hypochondriac region. The abdominal wall Fig. 1.1. Various regions of the anterior abdominal wall should be suspected as the source of the pain in indi- viduals who exhibit chronic and unremitting pain with minimal or no relationship to gastrointestinal func- the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra. The sub- tion, but which shows variation with changes of pos- costal plane that passes across the costal margins and ture [1]. This is also true when the anterior abdominal the upper border of the third lumbar vertebra may be wall tenderness is unchanged or exacerbated upon con- used instead of the transpyloric plane. -

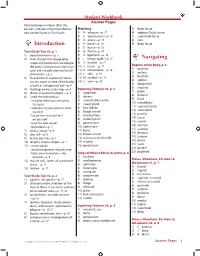

Student Workbook Answer Pages Italicized Page Numbers After the Answers Indicate Where the Informa- Matching 5) Deep Fascia Tion Can Be Found in Trail Guide

Student Workbook Answer Pages Italicized page numbers after the answers indicate where the informa- Matching 5) deep fascia tion can be found in Trail Guide. 1) N adipose—p. 17 6) adipose (fatty) tissue 2) F aponeurosis—p. 13 7) superficial fascia 3) D artery—p. 16 8) skin 4) H bone—p. 10 9) deep fascia Introduction 5) E bursa—p. 16 Tour Guide Tips #1, p. 1 6) B fascia—p. 14 1) bony landmarks—p. 2 7) G ligament—p. 13 2) Even though the topography, 8) I lymph node—p. 17 Navigating shape and proportion are unique, 9) A muscle—p. 11 Regions of the Body, p. 6 the body’s composition and struc- 10) J nerve—p. 17 1) pectoral tures are virtually identical on all 11) K retinaculum—p. 15 2) axillary individuals.—p. 2 12) L skin—p. 10 3) brachial 3) To examine or explore by touch- 13) M tendon—p. 13 4) cubital ing (an organ or area of the body), 14) C vein—p. 16 5) abdominal usually as a diagnostic aid—p. 4 6) inguinal 4) locating, aware, assessing—p. 4 Exploring Textures #1, p. 3 7) pubic 5) directs movement, depth.—p. 4 1) epidermis 8) femoral 6) • read the information 2) dermis 9) facial • visualize what you are trying 3) arrector pili muscle 10) mandibular to access 4) sweat gland 11) supraclavicular • verbalize to your partner what 5) hair follicle 12) antecubital you feel 6) blood vessels 13) patellar • locate the structure first 7) muscle fibers 14) crural on yourself 8) endomysium 15) cranial • read the text aloud 9) perimysium 16) cervical • be patient—p. -

Pelvic Girdle Pain Copyright 2010 the Brigham and Women's Hospital

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Pelvic girdle pain Physical Therapy management of the patient with pelvic girdle pain (also referred to as posterior pelvic pain), ante and post partum, as well as, the non-pregnant population. Sacroiliac Joint Pain Syndromes in pregnancy. ICD 9 code: 719.45-pelvic joint pain, 720.2- sacroilitis, 724.3- sciatica, and 846.9- sacroiliac sprain Case Type / Diagnosis: Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) is defined by pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ). 12 PGP is a specific form of low back pain (LBP) that can occur separately or concurrently with LBP. The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis. 1,2 PGP generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, or reactive arthritis. The pain or functional disturbances in relation to PGP must be reproduced by specific clinical tests. 12 The endurance capacity for standing, walking and sitting is diminished.2. Studies have indicated that 47-49% of pregnant women experience some form of back pain during their pregnancy. 3,4PGP has an incidence of 20% in the pregnant population. 2 When a pregnant patient presents with back pain it is critical to differentiate whether the patient has PGP or lumbar pain as each condition require a different treatment approach. PGP does not present with sensory changes or weakness, which differentiates PGP from lumbar radiculopathy. 4 Patients can have low back pain and PGP concurrently with an incidence of 8%.