A Temporary Androgyne for Lynda Benglis and Richard Tuttle)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

David Zwirner Tomma Abts

David Zwirner New York London Paris Hong Kong Tomma Abts November 6–December 14, 2019 533 West 19th Street, New York Opening reception: Wednesday, November 6, 6–8 PM Tomma Abts, Samke, 2019. Photo © Marcus Leith. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner New York David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by Tomma Abts at the gallery’s 533 West 19th Street location in New York. Included in the exhibition will be paintings from two distinct but related bodies of work that, in different ways, showcase Abts’s sustained engagement with process and form. This will be the artist’s third solo presentation with the gallery and her first exhibition in New York since 2014. Abts is known for her complex paintings and drawings, the subject of which is ultimately the process of their creation. Working in accordance with a self-determined and evolving set of parameters, the artist enacts a series of decisions, which results in compositions that are intuitively constructed according to an internal logic. While abstract, her paintings are nevertheless illusionistic, rendered with sharp attention to details—such as shadows, three-dimensional effects, and highlights—that defy any single, realistic light source. As she has noted, “Making a painting is a long-winded process of finding a form for something intuited … and making whatever shape and form it takes as clear and precise as possible.”1 Begun in 1998, Abts’s body of intimately scaled canvases—which uniformly measure approximately 19 by 15 inches (48 by 38 centimeters)—are created entirely freehand and without preconceived ideas or preliminary sketches. -

Tomma Abts Tomma Abts

Tomma Abts Tomma Abts Foreword by Lisa Phillips Essays by Laura Hoptman Jan Verwoert and Bruce Hainley Contents Foreword 6 Lisa Phillips Acknowledgments 8 Laura Hoptman Tomma Abts: Art for an Anxious Time 10 Laura Hoptman Paintings 17 The Beauty and Politics of Latency: On the Work of Tomma Abts 92 Jan Verwoert Drawings 99 Margit Carstensen’s Blog 120 Bruce Hainley Paintings in the Exhibition 133 Biography 134 Bibliography 136 Contributors 139 Foreword Tomma Abts’ paintings have been described as Bruce Hainley and Jan Verwoert also Toby Devan Lewis Emerging Artists Exhibitions quiet, uncanny, and disquieting. They seem contributed texts to the book that greatly Fund, and support for the publication by the J. autonomous; her uncompromising biomorphic illuminate Abts’ work. Hainley’s blog-inspired text McSweeney and G. Mills Publications Fund at the and geometric forms do not portray a subject not only offers a narrative of personal discovery New Museum. but instead, in the artist’s own words, become and examination of Abts’ paintings, but the blog We deeply appreciate the cooperation of the something “quite physical and therefore ‘real.’” structure presents an interesting parallel to lenders to the exhibition, who are thanked individually It is the strange and evocative presence of these Abts’ process. Verwoert’s essay is an engrossing elsewhere. Finally, I want to give my thanks to the paintings, along with the questions they pose look at the politics of abstraction, and he offers entire New Museum staff for their efforts in to current discourses in painting, that make this clear reasons why Abts’ work is so relevant to our bringing Tomma Abts’ work to a wider audience. -

Homage to the Square, 1958, Installation Shot, Architecture Studio, 2Nd FL (The Bank), Marfa, Texas 49

48 Homage to the Square, 1958, installation shot, Architecture Studio, 2nd FL (The Bank), Marfa, Texas 49 Jailbreaking Geometric Abstraction 1 A wide array of work in both these E v a D í a z categories was showcased in the 2008 art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York Color Chart: Reinventing Color from 1950 to Today. Organized by curator I There are no “masterpieces” in Josef Albers’ career. His work Ann Temkin, Color Chart’s exhibi- tion strategy toggled between most often emerges, in series, from the success of its forerunner to treating color as a ready-made— initiate the exploration of its successor. Nor did Albers cultivate emphasizing artist’s use of unmixed paint and paint chips (in this vein disciples. It must be remembered that his students followed diverse Frank Stella’s quip, “I tried to keep trajectories even as they credited him as an important mentor. the paint as good as it was in the can,” was mentioned in the show’s So what, then, can be said to be the legacy of Josef Albers today? press release and subsequently quoted in the New York Times If no one artwork, no one thread of inheritance, encapsulates the review of the exhibition)—and “Josef Albers model,” it is because the method itself is the galvanic Albers’ notion of the relativity and relationality of color perception. element of his work: Albers’ practice of experimental testing towards 2 pedagogical ends wields growing infuence today. According to a 2012 article, Tomma Abts’ 48 × 38 cm paintings (the stan- dardized size she works in) go for $120,000. -

Tate St Ives Presents the Indiscipline of Painting: International Abstraction from the 1960S to Now October 2011

Artdaily.org Tate St Ives presents The Indiscipline of Painting: International abstraction from the 1960s to now October 2011 Tate St Ives presents The Indiscipline of Painting: International abstraction from the 1960s to now Bernard Frize, Suite Segond 100 No 3, 1980. Alkyd Urethane lacquer on canvas, 162 x 130 cm. Collection of the artist, courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, London. CORNWALL.- The Indiscipline of Painting is an international group exhibition including works by forty-nine artists from the 1960s to now. Selected by British painter Daniel Sturgis, it considers how thelanguages of abstraction have remained urgent, relevant and critical as they have been revisited and reinvented by subsequent generations of artists over the last 50 years. It goes on to demonstrate the way in which the history and legacy of abstract painting continues to inspire artists working today. The contemporary position of abstract painting is problematic. It can be seen to be synonymous with a modernist moment that has long since passed, and an ideology which led the medium to stagnate in self-reflexivity and ideas of historical progression. The exhibition challenges such assumptions. It reveals how painting's modernist histories, languages and positions have continued to provoke ongoing dialogues with contemporary practitioners, even as painting's decline and death has been routinely and erroneously declared. The show brings together works by British, American and European artists made over the last five decades and features major new commissions and loans. It includes important works by Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Gerhard Richter and Bridget Riley alongside artists such as Tomma Abts, Martin Barré and Mary Heilmann. -

Artnet News - Artnet Magazine

1/12/2017 Artnet News - artnet Magazine Search Artists Galleries Auction Houses Events Auctions News artnet Magazine ARTNET NEWS News May 19, 2006 Reviews TURNER PRIZE SHORTLIST ANNOUNCED Features The shortlist for the 2006 Turner Prize has been announced, featuring a group Books of artists who are rather fresh, especially to U.S. audiences: 38yearold Tomma Abts, an abstract painter who has showed at the Wrong Gallery and People is presently represented by greengrassi; 35yearold video artist Phil Collins, last seen in New York with an exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery featuring Videos disaffected youths from the streets of Istanbul belting out karaoke renditions of Horoscope songs by The Smiths; 33yearold mixedmedia artist Mark Titchner, known for drawing on billboard art and corporate logos; and 41yearold Rebecca Newsletter Warren, who is represented by Matthew Marks and creates voluptuous, blob Spencer’s Art Law Journal like sculptures of women. Subscribe to our RSS feed: The British tabloid press has, rather predictably, latched onto the big breasts of Warren's sculptures as this year's scandal, referring to the artist as a "pervy potter" (though if an obsession with outsized breasts be a crime, its hard to imagine the British tabloid press being in a position to say anything about it). Fans can judge for themselves when an exhibition of work by the finalists opens at the Tate, Oct. 3, 2006Jan. 21, 2007. The 2006 Turner jury consists of Lynn Barber, Margot Heller, Matthew Higgs, Andrew Renton and Tate director Nicholas Serota, and announces the winner of the £25,000 prize on Dec. -

David Zwirner Tomma Abts

David Zwirner New York London Paris Hong Kong Tomma Abts November 6–December 14, 2019 533 West 19th Street, New York Opening reception: Wednesday, November 6, 6–8 PM Tomma Abts, Samke, 2019. Photo © Marcus Leith. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner New York David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by Tomma Abts at the gallery’s 533 West 19th Street location in New York. Included in the exhibition will be paintings from two distinct but related bodies of work that, in different ways, showcase Abts’s sustained engagement with process and form. This will be the artist’s third solo presentation with the gallery and her first exhibition in New York since 2014. Abts is known for her complex paintings and drawings, the subject of which is ultimately the process of their creation. Working in accordance with a self-determined and evolving set of parameters, the artist enacts a series of decisions, which results in compositions that are intuitively constructed according to an internal logic. While abstract, her paintings are nevertheless illusionistic, rendered with sharp attention to details—such as shadows, three-dimensional effects, and highlights—that defy any single, realistic light source. As she has noted, “Making a painting is a long-winded process of finding a form for something intuited … and making whatever shape and form it takes as clear and precise as possible.”1 Begun in 1998, Abts’s body of intimately scaled canvases—which uniformly measure approximately 19 by 15 inches (48 by 38 centimeters)—are created entirely freehand and without preconceived ideas or preliminary sketches. -

Lizzie Lloyd Thesis FINAL Feb 2019

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Lloyd, Lizzie Title: Art Writing and Subjectivity Critical Association in Art-Historical Practice General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Art Writing and Subjectivity: Critical Association in Art-Historical Practice Lizzie Lloyd A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Arts. -

The Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery Annual Accounts 2011-2012

The Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery Annual Accounts 2011-2012 HC 475 LONDON: The Stationery Office £11.75 The Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery Annual Accounts 2011-2012 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 12 JULY 2012 HC 475 LONDON: The Stationery Office £11.75 © Tate Gallery 2012 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Tate Gallery copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.tate.org.uk ISBN: 9780102977431 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2487699 07/12 22128 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Contents Page Advisers 2 Annual report 3 Foreword 15 Remuneration report 24 Statement of Trustees’ and Director’s responsibilities 27 Governance statement 28 The certificate and report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament 36 Consolidated statement of financial activities 38 Consolidated balance sheet 40 Tate balance sheet 41 -

Tate Report 2013/14 2 Working with Art and Artists

TATE REPORT 2013 /14 2 WORKING WITH ART AND ARTISTS The renovation of Tate Britain by architects Caruso St John includes a spectacular new staircase and a new Members Room overlooking the historic Rotunda TATE REPORT 2013/14 It is the exceptional generosity and vision of If you would like to find out more about how individuals, corporations and numerous private you can become involved and help support foundations and public sector bodies that have Tate, please contact us at: helped Tate to become what it is today and enabled us to: Development Office Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions and Millbank collection displays London SW1P 4RG Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative education and Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8098 interpretation programmes Tate Americas Foundation Strengthen and extend the range of our 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 collection, and conserve and care for it New York, NY 10001 USA Advance innovative scholarship and research Tel +1 212 643 2818 Fax +1 212 643 1001 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and continue to meet the needs of our visitors Or visit us at www.tate.org.uk/support Establish dynamic partnerships in the UK and across the world. CONTENTS CHairman’S Foreword 3 WORKING WITH ART AND ARTISTS The new Tate Britain 9 Exhibitions and displays 11 The collection 16 Caring for the collection 21 Deepening understanding 22 TATE MODERN EXHIBITIONS ART AND ITS IMPACT Working with audiences in the UK 29 Connecting with local communities 34 Audiences around the world 36 Reaching young people 41 Learning programmes in a changing world 42 Digital audiences 47 TATE BRITAIN EXHIBITIONS MAKING IT HAPPEN Working towards Tate’s vision 55 Funding and supporters 56 TATE ST IVES EXHIBITIONS LOOKING AHEAD 65 TATE LIVERPOOL EXHIBITIONS ACQUISITION HIGHLIGHTS 71 FINANCE AND statistics 91 DONATIONS, GIFTS, LEGACIES AND SPONSORSHIPS 99 3 CHAIRMan’S ForeWorD The Trustees and staff of Tate spent much of last year discussing a mysterious painting called ‘The Fisherman’. -

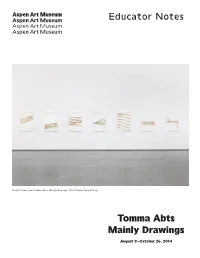

Educator Notes Tomma Abts Mainly Drawings

Educator Notes Installation view: Tomma Abts, Mainly Drawings, 2014. Photo: Tony Prikryl Tomma Abts Mainly Drawings August 9–October 26, 2014 About the artist Tomma Abts was born in 1967 in Kiel, Germany, and has lived and worked in London since 1995. She is primarily known for her acrylic and oil paintings, which feature repetitive, geometric, abstract forms. Most of her artworks are consistent in size, but diverse in the use of color, and maintain a strong use of negative space. In 2006, Abts was the recipient of the Turner Prize, awarded by the Tate in London. Installation view: Tomma Abts, Mainly Drawings, 2014. Photo: Tony Prikryl About the exhibition Tomma Abts’s rigorous working process of depth and movement through the various combines the rational with the intuitive. uses of lines. Because she generally does Starting with no external source material not create her drawings and paintings and no preconceived idea of the final with a set plan, she uses great control and result, she creates complex abstract precision in her execution to achieve a compositions that ultimately take as their pristine quality. subject the process of their own creation. Abts does not say too much about her Abts’s exhibition at the Aspen Art Museum work, preferring that we develop our is the first to survey the artist’s extensive own subjective relationships with these drawing practice. The exhibition features drawings. She has commented, “Most forty-one works from 1996 to the present, painters have the experience that painting including new works created specifically ‘happens’ not when you try really hard, but for the exhibition.