Palliative Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor

mAChR Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor mAChRs (muscarinic acetylcholine receptors) are acetylcholine receptors that form G protein-receptor complexes in the cell membranes of certainneurons and other cells. They play several roles, including acting as the main end-receptor stimulated by acetylcholine released from postganglionic fibersin the parasympathetic nervous system. mAChRs are named as such because they are more sensitive to muscarine than to nicotine. Their counterparts are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), receptor ion channels that are also important in the autonomic nervous system. Many drugs and other substances (for example pilocarpineand scopolamine) manipulate these two distinct receptors by acting as selective agonists or antagonists. Acetylcholine (ACh) is a neurotransmitter found extensively in the brain and the autonomic ganglia. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 mAChR Inhibitors & Modulators (+)-Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate (-)-Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate Cat. No.: HY-76772A Cat. No.: HY-76772B Bioactivity: Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate, a novel muscarinic Bioactivity: Cevimeline hydrochloride hemihydrate, a novel muscarinic receptor agonist, is a candidate therapeutic drug for receptor agonist, is a candidate therapeutic drug for xerostomia in Sjogren's syndrome. IC50 value: Target: mAChR xerostomia in Sjogren's syndrome. IC50 value: Target: mAChR The general pharmacol. properties of this drug on the The general pharmacol. properties of this drug on the gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive systems and other… gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive systems and other… Purity: >98% Purity: >98% Clinical Data: No Development Reported Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 10mM x 1mL in DMSO, Size: 10mM x 1mL in DMSO, 1 mg, 5 mg 1 mg, 5 mg AC260584 Aclidinium Bromide Cat. No.: HY-100336 (LAS 34273; LAS-W 330) Cat. -

Viewed the Existence of Multiple Muscarinic CNS Penetration May Occur When the Blood-Brain Barrier Receptors in the Mammalian Myocardium and Have Is Compromised

BMC Pharmacology BioMed Central Research article Open Access In vivo antimuscarinic actions of the third generation antihistaminergic agent, desloratadine G Howell III†1, L West†1, C Jenkins2, B Lineberry1, D Yokum1 and R Rockhold*1 Address: 1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA and 2Tougaloo College, Tougaloo, MS, USA Email: G Howell - [email protected]; L West - [email protected]; C Jenkins - [email protected]; B Lineberry - [email protected]; D Yokum - [email protected]; R Rockhold* - [email protected] * Corresponding author †Equal contributors Published: 18 August 2005 Received: 06 October 2004 Accepted: 18 August 2005 BMC Pharmacology 2005, 5:13 doi:10.1186/1471-2210-5-13 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2210/5/13 © 2005 Howell et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Muscarinic receptor mediated adverse effects, such as sedation and xerostomia, significantly hinder the therapeutic usefulness of first generation antihistamines. Therefore, second and third generation antihistamines which effectively antagonize the H1 receptor without significant affinity for muscarinic receptors have been developed. However, both in vitro and in vivo experimentation indicates that the third generation antihistamine, desloratadine, antagonizes muscarinic receptors. To fully examine the in vivo antimuscarinic efficacy of desloratadine, two murine and two rat models were utilized. The murine models sought to determine the efficacy of desloratadine to antagonize muscarinic agonist induced salivation, lacrimation, and tremor. -

Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptors in Developing Rat Lung

1136 WHITSETT AND HOLLINGER Am J Obstet Gynecol 126:956 Michaelis LL 1978 The effects of arterial COztension on regional myocardial 2. Belik J, Wagerle LC, Tzimas M, Egler JM, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M 1983 and renal blood flow: an experimental study. J Surg Res 25:312 Cerebral blood flow and metabolism following pancuronium paralysis in 18. Leahy FAN. Cates D. MacCallum M. Rigatto H 1980 Effect of COz and 100% newborn lambs. Pediatr Res 17: 146A (abstr) O2 on cerebral blood flow in preterm infants. J Appl Physiol48:468 3. Berne RM, Winn HR, Rubio R 1981 The local regulation of cerebral blood 19. Norman J, MacIntyre J, Shearer JR, Craigen IM, Smith G 1970 Effect of flow. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 24:243 carbon dioxide on renal blood flow. Am J Physiol 219:672 4. Brann AW Jr, Meyers RE 1975 Central nervous system findings in the newborn 20. Nowicki PT, Stonestreet BS, Hansen NB, Yao AC, Oh W 1983 Gastrointestinal monkey following severe in utero partial asphyxia. Neurology 25327 blood flow and oxygen in awake newborn piglets: the effect of feeding. Am 5. Bucciarelli RL, Eitzman DV 1979 Cerebral blood flow during acute acidosis J Physiol245:G697 in perinatal goats. Pediatr Res 13: 178 21. Paulson OB, Olesen J, Christensen MS 1972 Restoration of auto-regulation of 6. Dobbing J, Sands J 1979 Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early cerebral blood flow by hypocapnia. Neurology 22:286 Hum Dev 3:79 22. Peckham GJ. Fox WW 1978 Physiological factors affecting pulmonary artery 7. Fox WW 1982 Arterial blood gas evaluation and mechanical ventilation in the pressure in infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension.J Pediatr 93: 1005 management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the neonate. -

Role of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Adult Neurogenesis and Cholinergic Seizures

Role of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Adult Neurogenesis and Cholinergic Seizures Rebecca L. Kow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reding Committee: Neil Nathanson, Chair Sandra Bajjalieh Joseph Beavo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Pharmacology ©Copyright 2014 Rebecca L. Kow University of Washington Abstract Role of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Adult Neurogenesis and Cholinergic Seizures Rebecca L. Kow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Neil M. Nathanson Department of Pharmacology Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that mediate important functions in the periphery and in the central nervous systems. In the brain these receptors modulate many processes including learning, locomotion, pain, and reward behaviors. In this work we investigated the role of mAChRs in adult neurogenesis and further clarified the regulation of muscarinic agonist-induced seizures. We first investigated the role of mAChRs in adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the subgranular zone (SGZ). We were unable to detect any modulation of adult neurogenesis by mAChRs. Administration of muscarinic agonists or antagonists did not alter proliferation or viability of adult neural progenitor cells (aNPCs) in vitro. Similarly, muscarinic agonists did not alter proliferation or survival of new adult cells in vivo. Loss of the predominant mAChR subtype in the forebrain, the M1 receptor, also caused no alterations in adult neurogenesis in vitro or in vivo, indicating that the M1 receptor does not mediate the actions of endogenous acetylcholine on adult neurogenesis. We also investigated the interaction between mAChRs and cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) in muscarinic agonist pilocarpine-induced seizures. -

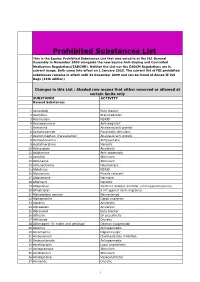

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently?

life Review Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently? Hosna Mohammad Sadeghi 1,†, Ida Adeli 1,† , Taraneh Mousavi 1,2, Marzieh Daniali 1,2, Shekoufeh Nikfar 3,4,5 and Mohammad Abdollahi 1,2,* 1 Toxicology and Diseases Group (TDG), Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC), The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] (H.M.S.); [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (M.D.) 2 Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 3 Personalized Medicine Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] 4 Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC) and the Pharmaceutical Management and Economics Research Center (PMERC), Evidence-Based Evaluation of Cost-Effectiveness and Clinical Outcomes Group, The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 5 Department of Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Administration, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equally contributed as first authors. Citation: Mohammad Sadeghi, H.; Abstract: A slow rate of new drug discovery and higher costs of new drug development attracted Adeli, I.; Mousavi, T.; Daniali, M.; the attention of scientists and physicians for the repurposing and repositioning of old medications. Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Drug Experimental studies and off-label use of drugs have helped drive data for further studies of ap- Repurposing for the Management of proving these medications. -

![[3H]Acetylcholine to Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptors’](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7448/3h-acetylcholine-to-muscarinic-cholinergic-receptors-1087448.webp)

[3H]Acetylcholine to Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptors’

0270.6474/85/0506-1577$02.00/O The Journal of Neuroscience CopyrIght 0 Smety for Neurosmnce Vol. 5, No. 6, pp. 1577-1582 Prrnted rn U S.A. June 1985 High-affinity Binding of [3H]Acetylcholine to Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptors’ KENNETH J. KELLAR,2 ANDREA M. MARTINO, DONALD P. HALL, Jr., ROCHELLE D. SCHWARTZ,3 AND RICHARD L. TAYLOR Department of Pharmacology, Georgetown University, Schools of Medicine and Dentistry, Washington, DC 20007 Abstract affinities (Birdsall et al., 1978). Evidence for this was obtained using the agonist ligand [3H]oxotremorine-M (Birdsall et al., 1978). High-affinity binding of [3H]acetylcholine to muscarinic Studies of the actions of muscarinic agonists and detailed analy- cholinergic sites in rat CNS and peripheral tissues was meas- ses of binding competition curves between muscarinic agonists and ured in the presence of cytisin, which occupies nicotinic [3H]antagonists have led to the concept of muscarinic receptor cholinergic receptors. The muscarinic sites were character- subtypes (Rattan and Goyal, 1974; Goyal and Rattan, 1978; Birdsall ized with regard to binding kinetics, pharmacology, anatom- et al., 1978). This concept was reinforced by the discovery of the ical distribution, and regulation by guanyl nucleotides. These selective actions and binding properties of the antagonist pirenze- binding sites have characteristics of high-affinity muscarinic pine (Hammer et al., 1980; Hammer and Giachetti, 1982; Watson et cholinergic receptors with a Kd of approximately 30 nM. Most al., 1983; Luthin and Wolfe, 1984). An evolving classification scheme of the muscarinic agonist and antagonist drugs tested have for these muscarinic receptors divides them into M-l and M-2 high affinity for the [3H]acetylcholine binding site, but piren- subtypes (Goyal and Rattan, 1978; for reviews, see Hirschowitz et zepine, an antagonist which is selective for M-l receptors, al., 1984). -

208151Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 208151Orig1s000 SUMMARY REVIEW NDA 208151, ISOPTO Atropine (atropine sulfate ophthalmic solution) 1% Cycloplegia, Mydriasis, Penalization of the healthy eye in the treatment of amblyopia Division Director Summary Review Material Reviewed/Consulted OND Action Package, including: Names of discipline reviewers Medical Officer Review Wiley Chambers, William Boyd 9/13/2016 CDTL Review William Boyd, Wiley Chambers 11/29/2016 Statistical Review Abel Eshete, Yan Wang 11/8/2016 Pharmacology Toxicology Review Aaron Ruhland, Lori Kotch 11/7/2016 CMC Review Haripada Sanker, Milton Sloan, Maotang Zhou, Denise Miller, Vidya Pai, Om Anand, Erin Andrews, Chunchun Zhang, Paul Perdue 10/12/2016, 11/10/2016 Clinical Pharmacology Review Abhay Joshi, Philip Colangelo 11/9/2016 OPDP/DPDP Carrie Newcomer 11/7/2016 OSI/DGCPC N/A Proprietary Name Michelle Rutledge, Yelena Maslov, Lubna Merchant 6/1/2016 Conditionally acceptable letter Todd Bridges 6/2/2016 OSE/DMEPA Michelle Rutledge, Yelena Maslov 6/8/2016 OSE/DDRE N/A OSE/DRISK N/A Project Manager Michael Puglisi OND=Office of New Drugs CDTL=Cross-Discipline Team Leader OSI/DGCPC=Office of Scientific Investigations/Division of Good Clinical Practice Compliance OPDP/DPDP=Office of Prescription Drug Promotion/Division of Prescription Drug Promotion OSE= Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology DMEPA=Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis DDRE= Division of Drug Risk Evaluation DRISK=Division of Risk Management Page 2 of 24 Reference ID: 4021108 NDA 208151, ISOPTO Atropine (atropine sulfate ophthalmic solution) 1% Cycloplegia, Mydriasis, Penalization of the healthy eye in the treatment of amblyopia Division Director Summary Review Signatory Authority Review Template 1. -

Inhaled Bronchodilator – Muscarinic Antagonist Medication

Inhaled Bronchodilator – Muscarinic Antagonist Medication Inhaled Bronchodilator ~ Muscarinic Antagonist Medication ~ Other names for this medication: Short-Acting: Atrovent – ipratropium bromide Long-Acting: Incruse – umeclidinium Incruse – umeclidinium bromide Seebri – glycopyrronium bromide Spiriva – tiotropium bromide Tudorza – aclidinium bromide How does this medication work? This medication helps the muscles around the bronchial tubes in the lungs to relax. This widens or bronchodilates the tubes and improves breathing. This medication also makes the muscle less likely to contract and narrow the tubes in response to exercise, cold air and irritants such as dust and cigarette smoke. How fast and long does this medication work? Atrovent: This depends on how you are advised to use it. It takes about 5 to 15 minutes to begin working. The effects can last for 4 to 6 hours. Incruse: Begins to work within 30 to 60 minutes. Seebri: Begins to work within 5 to 15 minutes. Spiriva: Begins to work within 30 to 60 minutes. Tudorza: Begins to work within 30 to 60 minutes. Please turn over 1 Inhaled Bronchodilator – Muscarinic Antagonist Medication How much medication do I take and how often? Take this medication on a regular basis as directed by your doctor. While taking this medication you may notice: headache dry mouth bad taste in mouth constipation Dry mouth often goes away. If not, talk to your health care provider about what you can do to help. Consult your doctor if: this medication is less effective than usual you have trouble passing urine If any of these occur, you may need other treatment. PD 6229 (Rev 03-2016) 2 . -

Nitric Oxide and Anticholinergic Effects in Normal and Inflamed Urinary Bladders in Anaesthetized Rats

421 Andersson M1, Giglio D1, Tobin G1 1. Neuroscience and physiology NITRIC OXIDE AND ANTICHOLINERGIC EFFECTS IN NORMAL AND INFLAMED URINARY BLADDERS IN ANAESTHETIZED RATS Hypothesis / aims of study In the current study it was wondered if muscarinic whole bladder contractile responses are affected by cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis in vivo, and further, if nitric oxide influences cholinergic responses differently in the inflamed than in the normal urinary bladder of anaesthetized rats. Study design, materials and methods 22 male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-350 g) were used. They were anaesthetized with pentobarbitone (45 mg.kg -1 I.P.) followed by supplementary I.V doses when required. The trachea was cannulated and the body temperature was maintained at about 38°C using a thermostatically controlled blanket connected to a rectal thermister. The blood pressure was measured continuously via a femoral arterial catheter. A femoral venous cannula was used for all drug administrations. The urinary bladder pressure was measured continuously via a catheter inserted through a small incision and fixed at the top of the bladder. By injection of small saline volumes the pressure was kept at 10 to 15 mmHg; during stable anaesthesia, the variation of basal bladder pressure was minute. Methacholine was injected intravenously in successively increasing doses (1 – 5 µg.kg -1 I.V.). Two different protocols were then used. Either a standard dose of methacholine (2 µg.kg -1 I.V.) was given repeatedly before and after administration of the muscarinic antagonist 4-DAMP (4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine) at increasing doses (0.1 – 1000 µg.kg -1 I.V.). -

Antimuscarinic Actions of Antihistamines on the Heart

Journal of Biomedical Science (2006) 13:395–401 395 DOI 10.1007/s11373-005-9053-7 Antimuscarinic actions of antihistamines on the heart Huiling Liu, Qi Zheng & Jerry M. Farley* Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 N. State St., Jackson, MS, 39216-4505, USA Ó 2006 National Science Council, Taipei Key words: antihistamine, heart, Langendorff, muscarinic receptor, rat Summary Antimuscarinic side-effects, which include dry mouth, tachycardia, thickening of mucus possibly sedation, of the antihistamines limited the usefulness of these drugs. The advent of newer agents has reduced the sedative effect of the antihistamine. The data presented here show that one of the newest antihistamines, desloratadine, and a first generation drug, diphenhydramine, are both competitive inhibitors of muscarinic receptor mediated slowing of the heart as measured using a Langendorff preparation. Both agents have apparent sub-micromolar affinities for the muscarinic receptor. Two other agents, cetirizine and fexofen- adine, do not interact with muscarinic receptors in the heart at the concentrations used in this study. Structural similarities of the drugs suggest that substitution of a group with a high dipole moment or charge on the side chain nitrogen decreases the binding with muscarinic receptors. We conclude that of the compounds tested fexofenadine and cetirizine have little or no interaction with muscarinic receptors. The newest antihistamines, desloratadine, fexofen- micromolar concentrations [6] and therefore could adine and cetirizine, are metabolites of the older potentially interact on the heart through inhibition antihistamines, loratadine, terfenadine and of M2-muscarinic receptors. In this report we hydroxyzine [1]. All these compounds are selective examine the interaction of antihistamines with H1-histamine receptor antagonists. -

Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptors in Murine Lymphocytes: Demonstration by Direct Binding [3Hjquinuclidinyl Benzilate/Acetylcholine Receptors/Atropine) MICHAEL A

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 75, No. 6, pp. 2902-2904, June 1978 Immunology Muscarinic cholinergic receptors in murine lymphocytes: Demonstration by direct binding [3Hjquinuclidinyl benzilate/acetylcholine receptors/atropine) MICHAEL A. GORDON*, J. JOHN COHENt, AND IRWIN B. WILSON* * The Department of Chemistry, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309; and t The Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Colorado Medical Center, Denver, Colorado 80220 Communicated by George B. Koelle, March 17,1978 ABSTRACT Using [3Hjquinuclidinyl benzilate as a specific is a quasi-irreversible ligand, in that the dissociation of the cholinergic muscarinic ligand, it has been demonstrated that QNB-receptor complex is slow (15). Slowness of drug-receptor lymphocytes have muscarinic binding sites. There are ap- complex dissociation permits ready separation of unreacted proximately 200 sites per cell and the dissociation constant for quinuclidinyl benzilate is approximately 1 X 10- M. Quinuc [3H]QNB by rapid filtration and washing and allows quanti- lidinyl benzilate receptor binding is blocked by atropine and fication of binding sites per cell. The direct demonstration of oxotremorine. muscarinic binding sites and estimation of binding sites per cell appears fundamental in the study of cholinergic modulation Acetylcholine, released from cholinergic neurons, has been of lymphocyte function and metabolism. shown to interact with cholinergic receptors in skeletal muscle endplates, in cells of secretory glands, in ganglion cells of the MATERIALS AND METHODS autonomic nervous system, in smooth muscle, and in some cells [3-3H]Quinuclidinyl benzilate, specific activity 8.4 Ci/mmol, of the central nervous system (1). Acetylcholine receptors have was purchased from the Amersham/Searle Corp.