Partitioning & Transmutation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Transmutation Strategies for Management of Long-Lived Fission

PRAMANA c Indian Academy of Sciences Vol. 85, No. 3 — journal of September 2015 physics pp. 517–523 Nuclear transmutation strategies for management of long-lived fission products S KAILAS1,2,∗, M HEMALATHA2 and A SAXENA1 1Nuclear Physics Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai 400 085, India 2UM–DAE Centre for Excellence in Basic Sciences, Mumbai 400 098, India ∗Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.1007/s12043-015-1063-z; ePublication: 27 August 2015 Abstract. Management of long-lived nuclear waste produced in a reactor is essential for long- term sustenance of nuclear energy programme. A number of strategies are being explored for the effective transmutation of long-lived nuclear waste in general, and long-lived fission products (LLFP), in particular. Some of the options available for the transmutation of LLFP are discussed. Keywords. Nuclear transmutation; long-lived fission products; (n, γ ) cross-section; EMPIRE. PACS Nos 28.41.Kw; 25.40.Fq; 24.60.Dr 1. Introduction It is recognized that for long-term energy security, nuclear energy is an inevitable option [1]. For a sustainable nuclear energy programme, the management of long-lived nuclear waste is very critical. Radioactive nuclei like Pu, minor actinides like Np, Am and Cm and long-lived fission products like 79Se, 93Zr, 99Tc, 107Pd, 126Sn, 129I and 135Cs constitute the main waste burden from a power reactor. In this paper, we shall discuss the management strategies for nuclear waste in general, and long-lived fission products, in particular. 2. Management of nuclear waste The radioactive nuclei which are produced in a power reactor and which remain in the spent fuel of the reactor form a major portion of nuclear waste. -

Plasma–Material Interactions in Current Tokamaks and Their Implications for Next Step Fusion Reactors

Plasma–material interactions in current tokamaks and their implications for next step fusion reactors G. Federicia ITER Garching Joint Work Site, Garching, Germany C.H. Skinnerb Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA J.N. Brooksc Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA J.P. Coad JET Joint Undertaking, Abingdon, United Kingdom C. Grisolia Tore Supra, CEA Cadarache, St.-Paul-lez-Durance, France A.A. Haaszd University of Toronto, Institute for Aerospace Studies, Toronto, Ontario, Canada A. Hassaneine Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA V. Philipps Institut f¨ur Plasmaphysik, Forschungzentrum J¨ulich, J¨ulich, Germany C.S. Pitcherf MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA J. Roth Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Plasmaphysik, Garching, Germany W.R. Wamplerg Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA D.G. Whyteh University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA Nuclear Fusion, Vol. 41, No. 12R c 2001, IAEA, Vienna 1967 Contents 1. Introduction/background ........................................................................1968 1.1. Introduction....................................................................................1968 1.2. Plasma edge parameters and plasma–material interactions . 1969 1.3. History of plasma facing materials . 1973 2. Plasma edge and plasma–material interaction issues in next step tokamaks . 1977 2.1. Introduction....................................................................................1977 2.2. Progress towards a next step fusion device. .1977 2.3. Most prominent plasma–material interaction issues for a next step fusion device . 1980 2.4. Selection criteria for plasma facing materials. .1995 2.5. Overview of design features of plasma facing components for next step tokamaks. .1998 3. Review of physical processes and underlying theory ..........................................2002 3.1. Introduction....................................................................................2002 3.2. -

Depleted Uranium Technical Brief

Disclaimer - For assistance accessing this document or additional information,please contact [email protected]. Depleted Uranium Technical Brief United States Office of Air and Radiation EPA-402-R-06-011 Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC 20460 December 2006 Depleted Uranium Technical Brief EPA 402-R-06-011 December 2006 Project Officer Brian Littleton U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Radiation and Indoor Air Radiation Protection Division ii iii FOREWARD The Depleted Uranium Technical Brief is designed to convey available information and knowledge about depleted uranium to EPA Remedial Project Managers, On-Scene Coordinators, contractors, and other Agency managers involved with the remediation of sites contaminated with this material. It addresses relative questions regarding the chemical and radiological health concerns involved with depleted uranium in the environment. This technical brief was developed to address the common misconception that depleted uranium represents only a radiological health hazard. It provides accepted data and references to additional sources for both the radiological and chemical characteristics, health risk as well as references for both the monitoring and measurement and applicable treatment techniques for depleted uranium. Please Note: This document has been changed from the original publication dated December 2006. This version corrects references in Appendix 1 that improperly identified the content of Appendix 3 and Appendix 4. The document also clarifies the content of Appendix 4. iv Acknowledgments This technical bulletin is based, in part, on an engineering bulletin that was prepared by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air (ORIA), with the assistance of Trinity Engineering Associates, Inc. -

Spent Fuel Reprocessing

Spent Fuel Reprocessing Robert Jubin Oak Ridge National Laboratory Reprocessing of used nuclear fuel is undertaken for several reasons. These include (1) recovery of the valuable fissile constituents (primarily 235U and plutonium) for subsequent reuse in recycle fuel; (2) reduction in the volume of high-level waste (HLW) that must be placed in a geologic repository; and (3) recovery of special isotopes. There are two broad approaches to reprocessing: aqueous and electrochemical. This portion of the course will only address the aqueous methods. Aqueous reprocessing involves the application of mechanical and chemical processing steps to separate, recover, purify, and convert the constituents in the used fuel for subsequent use or disposal. Other major support systems include chemical recycle and waste handling (solid, HLW, low-level liquid waste (LLLW), and gaseous waste). The primary steps are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1. Aqueous Reprocessing Block Diagram. Head-End Processes Mechanical Preparations The head end of a reprocessing plant is mechanically intensive. Fuel assemblies weighing ~0.5 MT must be moved from a storage facility, may undergo some degree of disassembly, and then be sheared or chopped and/or de-clad. The typical head-end process is shown in Figure 2. In the case of light water reactor (LWR) fuel assemblies, the end sections are removed and disposed of as waste. The fuel bundle containing the individual fuel pins can be further disassembled or sheared whole into segments that are suitable for subsequent processing. During shearing, some fraction of the radioactive gases and non- radioactive decay product gases will be released into the off-gas systems, which are designed to recover these and other emissions to meet regulatory release limits. -

Advanced Reactors with Innovative Fuels

Nuclear Science Advanced Reactors with Innovative Fuels Workshop Proceedings Villigen, Switzerland 21-23 October 1998 NUCLEAR•ENERGY•AGENCY OECD, 1999. Software: 1987-1996, Acrobat is a trademark of ADOBE. All rights reserved. OECD grants you the right to use one copy of this Program for your personal use only. Unauthorised reproduction, lending, hiring, transmission or distribution of any data or software is prohibited. You must treat the Program and associated materials and any elements thereof like any other copyrighted material. All requests should be made to: Head of Publications Service, OECD Publications Service, 2, rue AndrÂe-Pascal, 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France. OECD PROCEEDINGS Proceedings of the Workshop on Advanced Reactors with Innovative Fuels hosted by Villigen, Switzerland 21-23 October 1998 NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: − to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; − to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and − to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. -

Episode 527: Nuclear Transmutation

9/28/2018 Episode 527: Nuclear transmutation Institute of Physics Search Home Electricity Mechanics Vibrations and waves Fields Atoms and nuclei Energy Astronomy You are here > Atoms and nuclei > Nuclear fission > Episode 527: Nuclear transmutation Nuclear fission Episode 527: Nuclear transmutation Episode 526: Preparation for nuclear fission topic Students need to move beyond the idea that nuclear changes are represented solely by alpha, beta and gamma decay. There are other decay processes, and there are other events that occur when a nucleus absorbs a particle and becomes unstable. Episode 527: Nuclear transmutation Episode 528: Controlling fission Summary Discussion: Transmutation of elements (15 minutes) Student questions: Balancing equations (30 minutes) Discussion: Induced fission (10 minutes) Demonstration: The nucleus as a liquid drop (10 minutes) Discussion: Fission products and radioactive waste (10 minutes) Worked example: A fission reaction (10 minutes) Discussion and demonstrations: Controlled chain reactions (15 minutes) Discussion: The possibility of fission (10 minutes) Student questions: Fission calculations (20 minutes) Discussion: Transmutation of elements Start by rehearsing some assumed knowledge. What is the nucleus made of? (Protons and neutrons, collectively know as nucleons.) What two natural processes change one element into another? (a and b decay). This is transmutation. Using a Periodic Table, explain that a decay moves two places down the periodic table. What about b- decay? (Moves one place up the periodic table.) Introduce the idea of b+ decay. (Moves one place down the periodic table.) Write general equations for these processes. There is another way in which an element may be transmuted; for example, the production of radioactive 14C used in radio- carbon dating in the atmosphere by the neutrons in cosmic rays. -

Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects

IAEA-TECDOC-1529 Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects February 2007 IAEA-TECDOC-1529 Management of Reprocessed Uranium Current Status and Future Prospects February 2007 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Nuclear Fuel Cycle and Materials Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria MANAGEMENT OF REPROCESSED URANIUM IAEA, VIENNA, 2007 IAEA-TECDOC-1529 ISBN 92–0–114506–3 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2007 Printed by the IAEA in Austria February 2007 FOREWORD The International Atomic Energy Agency is giving continuous attention to the collection, analysis and exchange of information on issues of back-end of the nuclear fuel cycle, an important part of the nuclear fuel cycle. Reprocessing of spent fuel arising from nuclear power production is one of the strategies for the back end of the fuel cycle. As a major fraction of spent fuel is made up of uranium, chemical reprocessing of spent fuel would leave behind large quantities of separated uranium which is designated as reprocessed uranium (RepU). Reprocessing of spent fuel could form a crucial part of future fuel cycle methodologies, which currently aim to separate and recover plutonium and minor actinides. The use of reprocessed uranium (RepU) and plutonium reduces the overall environmental impact of the entire fuel cycle. Environmental considerations will be important in determining the future growth of nuclear energy. It should be emphasized that the recycling of fissile materials not only reduces the toxicity and volumes of waste from the back end of the fuel cycle; it also reduces requirements for fresh milling and mill tailings. -

Background, Status and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities

NUREG-1909 Background, Status, and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities ACNW&M White Paper Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials NUREG-1909 Background, Status, and Issues Related to the Regulation of Advanced Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycle Facilities ACNW&M White Paper Manuscript Completed: May 2008 Date Published: June 2008 Prepared by A.G. Croff, R.G. Wymer, L.L. Tavlarides, J.H. Flack, H.G. Larson Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials THIS PAGE WAS LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY ii ABSTRACT In February 2006, the Commission directed the Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste and Materials (ACNW&M) to remain abreast of developments in the area of spent nuclear fuel reprocessing, and to be ready to provide advice should the need arise. A white paper was prepared in response to that direction and focuses on three major areas: (1) historical approaches to development, design, and operation of spent nuclear fuel recycle facilities, (2) recent advances in spent nuclear fuel recycle technologies, and (3) technical and regulatory issues that will need to be addressed if advanced spent nuclear fuel recycle is to be implemented. This white paper was sent to the Commission by the ACNW&M as an attachment to a letter dated October 11, 2007 (ML072840119). In addition to being useful to the ACNW&M in advising the Commission, the authors believe that the white paper could be useful to a broad audience, including the NRC staff, the U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, and other organizations interested in understanding the nuclear fuel cycle. -

A Review of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Strategies and the Spent Nuclear Fuel Management Technologies

energies Review A Review of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Strategies and the Spent Nuclear Fuel Management Technologies Laura Rodríguez-Penalonga * ID and B. Yolanda Moratilla Soria ID Cátedra Rafael Mariño de Nuevas Tecnologías Energéticas, Universidad Pontificia Comillas, 28015 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-91-542-2800 (ext. 2481) Received: 19 June 2017; Accepted: 6 August 2017; Published: 21 August 2017 Abstract: Nuclear power has been questioned almost since its beginnings and one of the major issues concerning its social acceptability around the world is nuclear waste management. In recent years, these issues have led to a rise in public opposition in some countries and, thus, nuclear energy has been facing even more challenges. However, continuous efforts in R&D (research and development) are resulting in new spent nuclear fuel (SNF) management technologies that might be the pathway towards helping the environment and the sustainability of nuclear energy. Thus, reprocessing and recycling of SNF could be one of the key points to improve the social acceptability of nuclear energy. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to review the state of the nuclear waste management technologies, its evolution through time and the future advanced techniques that are currently under research, in order to obtain a global vision of the nuclear fuel cycle strategies available, their advantages and disadvantages, and their expected evolution in the future. Keywords: nuclear energy; nuclear waste management; reprocessing; recycling 1. Introduction Nuclear energy is a mature technology that has been developing and improving since its beginnings in the 1940s. However, the fear of nuclear power has always existed and, for the last two decades, there has been a general discussion around the world about the future of nuclear power [1,2]. -

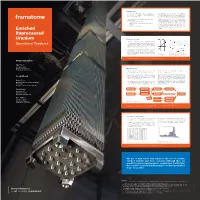

Operational Feedback Ventional Enriched FA

Background › Starting in 2009, Framatome has been supplying Size- › Totally Framatome has delivered more than 1000 FAs to well B* with fuel assemblies (FAs) with Enriched Re- Sizewell B, approximately half of them containing ERU. processed Uranium (ERU). The enrichment process of the reprocessed uranium is completed in Russia with an objective of minimizing even › Reprocessed uranium is understood as a secondary uranium isotopes such as 232U and 236U. The even isoto- uranium supply pes do not contribute to fi ssion; they are considered – by direct enrichment services to be an absorber and therefore, their presence needs to be minimized, which improves overall fuel utilization. – by blending with other feed material of a higher The low residual fraction of these parasitic isotopes is enrichment compensated by having slightly higher enrichment of 235U – by a combination of both to achieve equivalent reactivity to conventional enriched Enriched uranium.1,2 Reprocessed Uranium Neutronic Design › T he neutronic design of ERU FAs is designed for having the same reactivity characteristic as the equivalent con- Operational Feedback ventional enriched FA. This is achieved by the compen- sation of the 236U and other isotopes content through higher 235U enrichment (see fi g. 1 and 2). › Figure 2 shows the kinf versus the FA burn up of up to 80 MWd/kgU. Since the kinf values are very similar for ENU (enriched natural uranium) and ERU (enriched re- Fig. 2 Fig. 1 k comparison of ENU and ERU fuel versus processed uranium) fuel, the delta is shown as well in inf 235U compensation burn up – for neutronic FA design, upper the lower section. -

Reprocessing of Spent Nuclear Fuel

Reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen independent consultant member of the Nuclear Consulting Group November 2019 [email protected] Note In this document the references are coded by Q-numbers (e.g. Q6). Each reference has a unique number in this coding system, which is consistently used throughout all publications by the author. In the list at the back of the document the references are sorted by Q-number. The resulting sequence is not necessarily the same order in which the references appear in the text. reprocessing20191107 1 Contents Roots of reprocessing Once-through and closed-cycle systems Reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel Reprocessing and the Second Law Separation Purification Reprocessed uranium Plutonium Neptunium-237 Americium MOX fuel in LWRs Destruction of HEU and Pu: burning the Cold War legacy Uranium-plutonium breeder systems Reprocessing of FBR fuel Thorium for fission power Uranium-233 Molten-salt reactor Partitioning and transmutation Nuclear terrorism Vitrification Discharges Entropy generation by reprocessing Concluding notes References TABLES Table 1 Reprocessing plants world-wide Table 2 Discharges of radionuclides in the liquid and gaseous effluents of a reprocessing plant Table 3 Discharge limits of reprocessing plants to the sea Table 4 Discharge limits of reprocessing plants at La Hague FIGURES Figure 1 Mass composition of fresh and spent nuclear fuel Figure 2 Mass flows of reprocessing Figure 3 Outline of plutonium recycling in LWRs Figure 4 Outline of uranium-plutonium breeder cycle Figure 5 Principle of a partitioning and transmutation system Figure 6 Redistribution of the radioactive contents of spent fuel by reprocessing Figure 7 Symbolic representation of the entropy production by reprocessing reprocessing20191107 2 Roots of reprocessing Reprocessing technology has been developed during the late 1940s and during the Cold War to recover plutonium from spent fuel from special military reactors for the production of nuclear weapons. -

29. Nuclear Fusion-A Colossal Energy Source

International Journal of Scientific and Technical Advancements ISSN: 2454-1532 Nuclear Fusion-A Colossal Energy Source Snehashis Das1, Shamik Chattaraj2, Anjana Sengupta3, Kaustav Mallick4 1, 2, 3, 4Electrical Engineering, Technique Polytechnic Institute, Hooghly, West Bengal, India-712102 Email address: [email protected] Abstract— With the fast depletion of all other conventional forms of energy resources, it became very much essential to opt for alternative that will be abundant enough to last for quite an effective period of time. Lately, a lot of experimentation and projects are being undertaken to implement nuclear fusion to serve the above purpose. We are familiar with the term nuclear fission i.e. heavier elements breaking down into smaller particles releasing energy; whereas Nuclear Fusion is a phenomenon reverse of fission i.e. lighter elements unites to form heavier elements with release of energy of much greater magnitude compared to fission. In the process of fusion, the Coulomb’s Forces are much lesser compared to the binding energy of the resulting nuclei. The very first baby step towards research on fusion began in the year 1929. Building upon the nuclear transmutation experiments by Ernest Rutherford, carried out several years earlier, the laboratory fusion of hydrogen isotopes was first accomplished by Mark Oliphant in 1932. Later on, during Manhattan Project (1940), the concept of fusion was thought for the first time for military purpose, and many other followed after. Research for civil purpose began only in 1950s through thermonuclear fusion. Two projects, the National Ignition Facility and ITER were proposed for the purpose. Designs such as ICF & TOKAMAK are the mega sized reactors upon which world are looking forward to.