Television Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

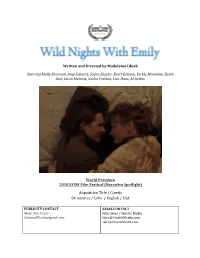

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

American Society

AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared By Ner Le’Elef AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared by Ner LeElef Publication date 04 November 2007 Permission is granted to reproduce in part or in whole. Profits may not be gained from any such reproductions. This book is updated with each edition and is produced several times a year. Other Ner LeElef Booklets currently available: BOOK OF QUOTATIONS EVOLUTION HILCHOS MASHPIAH HOLOCAUST JEWISH MEDICAL ETHICS JEWISH RESOURCES LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT ORAL LAW PROOFS QUESTION & ANSWERS SCIENCE AND JUDAISM SOURCES SUFFERING THE CHOSEN PEOPLE THIS WORLD & THE NEXT WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book One) WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book Two) For information on how to order additional booklets, please contact: Ner Le’Elef P.O. Box 14503 Jewish quarter, Old City, Jerusalem, 91145 E-mail: [email protected] Fax #: 972-02-653-6229 Tel #: 972-02-651-0825 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: PRINCIPLES AND CORE VALUES 5 i- Introduction 6 ii- Underlying ethical principles 10 iii- Do not do what is hateful – The Harm Principle 12 iv- Basic human rights; democracy 14 v- Equality 16 vi- Absolute equality is discriminatory 18 vii- Rights and duties 20 viii- Tolerance – relative morality 22 ix- Freedom and immaturity 32 x- Capitalism – The Great American Dream 38 a- Globalization 40 b- The Great American Dream 40 xi- Protection, litigation and victimization 42 xii- Secular Humanism/reason/Western intellectuals 44 CHAPTER TWO: SOCIETY AND LIFESTYLE 54 i- Materialism 55 ii- Religion 63 a- How religious is America? 63 b- Separation of church and state: government -

AGE Qualitative Summary

AGE Qualitative Summary Age Gender Race 16 Male White (not Hispanic) 16 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 17 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 18 Malel Blacklk or Africanf American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Female Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female White (p(not Hispanic)) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female Other 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 20 Female White (not Hispanic) 20 Female Other 20 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 20 Male Other 20 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 21 Female Don’t want to respond 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 21 Female White (not -

Wednesday Primetime B Grid

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/17/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA: Spotlight PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Cycling Tour of California, Stage 8. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Indianapolis 500, Qualifying Day 2. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Enough ›› (2002) 13 MyNet Paid Program Surf’s Up ››› (2007) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Dynamic Europe: Amsterdam Orphans of the Genocide 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Client ››› (1994) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido La Madrecita (1973, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Charlotte’s Web ››› (2006) Julia Roberts. -

Highly-Anticipated Fantasy Drama American Gods to Launch Exclusively on Amazon Prime Video in 2017

Highly-Anticipated Fantasy Drama American Gods to Launch Exclusively on Amazon Prime Video in 2017 August 24, 2016 Neil Gaiman’s tale of mythological gods, starring Ricky Whittle, Ian McShane, Emily Browning., Kristin Chenoweth and Gillian Anderson, will launch on Prime Video in Germany, Austria, UK and Japan next year Along with access to thousands of popular movies and TV episodes through Prime Video, Prime members across the UK benefit from unlimited One-Day delivery on millions of products, access to over one million songs on Prime Music, 30-minute early access to Lightning Deals, one free pre-released book a month with Kindle First and unlimited photo storage with Prime Photos — all available for a monthly membership of £7.99/month or £79/year London, Wednesday 24th August 2016 – Amazon today announced that fantasy drama American Gods will launch exclusively for Prime members in Germany, Austria, UK and Japan in 2017. The drama is based on the award-winning novel by Neil Gaiman (The Sandman, Good Omens, Coraline), which has been translated into over 30 languages. Starring Ricky Whittle (The 100, Austenland) as protagonist ex-con Shadow Moon, Ian McShane (Deadwood, Pirates of the Caribbean) as Mr. Wednesday who enlists Shadow Moon as part of his cross-country mission, and Emily Browning (Sucker Punch, Legend) as Shadow’s wife, Laura Moon, American Gods also features Gillian Anderson (The X-Files) as Media, the mouthpiece for the New Gods. Joining Whittle, McShane, Browning and Anderson are Pablo Schreiber (13 Hours, Orange Is the New Black) as Mad Sweeney, Yetide Badaki (Aquarius, Masters of Sex) as Bilquis and a strong supporting cast including, recently announced, Kristin Chenoweth, as Easter. -

British Actor Julian Sands Is Frequently Seen World- Wide in Films, on Stage, and on Television

British actor Julian Sands is frequently seen world- wide in films, on stage, and on television. He trained in London at The Central School of Speech and Drama and has appeared in over 100 films including; The Killing Fields, A Room With A View, Impromptu, Leaving Las Vegas, Arachnophobia, Oceans 13, and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. On television, he is best known for his role on 24 but has also been seen on Dexter, Smallville, Ghost Whisperer and Banshee. In 2005, Julian Sands was approached by the Nobel Prize winning playwright and poet Harold Pinter, to prepare a selection of his poems for a special presentation in London. Pinter “apprenticed” Mr. Sands, spending hours sharing his feelings on how his work should be delivered. Every pause, every nuance in tone, had, and has meaning. A bond was established between these two artists- one that gives a distinctive and very personal voice to Pinter’s words. This extraordinary collaboration became the foundation for a wonderfully rich, humorous, and fascinating solo show directed by John Malkovich- A Celebration of Harold Pinter. Performances at the Edinburgh Festival in 2011 and in New York at The Irish Repertory Theatre were followed by engagements at Steppenwolf in Chicago, Herbst Theatre in San Francisco as well as in Los Angeles, Mexico City, Budapest, London, and Paris. This is an evening of Homeric theater with an extraordinary actor, great words, and an audience. Devoid of pretension or glittery trappings, A Celebration of Harold Pinter gets to the soul of the man- poet, playwright, husband, political activist, Nobel winner, mortal. -

Fortean Times 338

THE X-FILES car-crash politics jg ballard versus ronald reagan cave of the witches south america's magical murders they're back: is the truth still out there? phantom fares japan's ghostly cab passengers THE WORLD’S THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTiMES.cOM FORTEAN TiMES 338 chimaera cats • death by meteorite • flat earth rapper • ancient greek laptop WEIRDES NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA www.forteantimes.com ft338 march 2016 £4.25 THE SEcRET HiSTORy OF DAviD bOWiE • RETuRN OF THE x-FiLES • cAvE OF THE WiTcHES • AuTOMATic LEPREcHAuNSP • jAPAN'S GHOST ACE ODDITY from aliens to the occult: the strange fascinations of daVid b0Wie FA RES bogey beasts the shape-shifting monsters of british folklore mystery moggies on the trail of alien big MAR 2016 cats in deepest suffolk Fortean Times 338 strange days Japan’s phantom taxi fares, John Dee’s lost library, Indian claims death by meteorite, cretinous criminals, curious cats, Harry Price traduced, ancient Greek laptop, Flat Earth rapper, CONTENTS ghostly photobombs, bogey beasts – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 05 EXTRA! EXTRA! 24 NECROLOG the world of strange phenomena 15 ALIEN ZOO 25 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 16 GHOSTWATCH 26 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 28 THE MAGE WHO SOLD THE WORLD From an early interest in UFOs and Aleister Crowley to fl irtations with Kabbalah and Nazi mysticism, David Bowie cultivated a number of esoteric interests over the years and embraced alien and occult imagery in his costumes, songs and videos. DEAN BALLINGER explores the fortean aspects and influences of the late musician’s career. -

Alan Sillitoe the LONELINESS of the LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER

Alan Sillitoe THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER Published in 1960 The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner Uncle Ernest Mr. Raynor the School-teacher The Fishing-boat Picture Noah's Ark On Saturday Afternoon The Match The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner AS soon as I got to Borstal they made me a long-distance cross-country runner. I suppose they thought I was just the build for it because I was long and skinny for my age (and still am) and in any case I didn't mind it much, to tell you the truth, because running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police. I've always been a good runner, quick and with a big stride as well, the only trouble being that no matter how fast I run, and I did a very fair lick even though I do say so myself, it didn't stop me getting caught by the cops after that bakery job. You might think it a bit rare, having long-distance crosscountry runners in Borstal, thinking that the first thing a long-distance cross-country runner would do when they set him loose at them fields and woods would be to run as far away from the place as he could get on a bellyful of Borstal slumgullion--but you're wrong, and I'll tell you why. The first thing is that them bastards over us aren't as daft as they most of the time look, and for another thing I'm not so daft as I would look if I tried to make a break for it on my longdistance running, because to abscond and then get caught is nothing but a mug's game, and I'm not falling for it. -

COMET Release FINAL

SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP AND METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER ANNOUNCE COMET , FIRST-EVER SCIENCE FICTION MULTI-CHANNEL NETWORK, TO PREMIERE ON OCTOBER 31 st Largest Multicast Network Launch with over 60% of the Country Reaching over 65M Homes (BALTIMORE & LOS ANGELES) October 19, 2015 – Sinclair Television Group, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (“Sinclair”), and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM ”), announced that COMET, the first-ever 24 hour/7 day per week science fiction multi-channel network, which will feature more than 1,500 hours of premium MGM content, will premiere in over 60% of the country and over 65 million homes on October 31 st of this year. The announcement was made today by David Amy, Chief Operating Officer of Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. and John Bryan, President, Domestic Television Distribution, MGM. The network will debut in all top markets including New York, NY; Los Angeles, CA; Chicago, IL; Philadelphia, PA; Seattle, WA; Denver, CO; St. Louis, MO; San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose, CA; Washington D.C.; Boston, MA; Pittsburgh, PA and Houston, TX. In addition to the Sinclair owned television stations, COMET will also launch on a number of Tribune and Titan stations. The network will feature a mix of science fiction, fantasy and adventure fan-favorites from MGM including television series such as “Outer Limits” and “Dead Like Me,” with the blockbusters “Stargate SG-1,” “Stargate Atlantis,” and “Stargate Universe” anchoring the primetime lineup. MGM films will play a crucial role in programming as well, with Moonraker and The Terminator featured during the premiere; Species and Leviathan will also be highlighted throughout the month . -

Movember in Molumbus Stickme: Acupuncture H

THe aLTernanve HeaLTOTssue insiDe: sociaLTsar ROBBie STePHens are YOU a STress mess? MOvemBer in moLumBus STICK me: acupuncTure HanDS on HeannG MaDLaB APOcaLYPse siLver Moon RisinG A LITTLe DOG I.aUGHeD inTerview: miKa OUT & PFOUD o ll74470"25134 ' 7 & LOCaL CeLeBIITY BLOGGerS by Erin McCalla 2010, the shop has been enthusiastically re ceived and increasingly successful. Greg's When I enter the Blue Star Barbershop, goal was to do 100 cuts a day, and Blue Star Johnny Cash is pumping through the speak has beaten that number... handily. ers. He's singing about shooting a man in Reno, just to watch him die and subsequently He explains that it's his superb staff that ending up in Folsom Prison. Johnny Cash keeps the clients coming back. Greg has his wouldn't get his haircut in a beauty salon, and employees go through a stringent screening if you're a man (or a lesbian with a short 'do), process before they even sharpen their neither should you. shears. This isn't your bargain bin buzz cut as each potential hire goes through three in That's because this locally (and queer) owned terviews and a technical try out that's why barbershop employs people who are really you can't get a better cut in town for the focused and adept at giving great haircuts, price. ($19!) tapers and fades to "smart men who want to look sharp." He's not knocking his swanky salon sisters and brothers, but Greg is passionate when it And speaking of sharp looking men, Greg comes to a man's mop and suggests that men Hund, the suave and sawy proprietor of Blue should stay away from salons with women- Star, opened this 9-chair shop two years ago based clienteles.