Experiencing and Cultivating Transformative Sustainability Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ken Wilber As a Spiritual Innovator. Studies in Integral Theory

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS UNIVERSITATIS ANNALES B 526 JP Jakonen KEN WILBER AS A SPIRITUAL INNOVATOR Studies in Integral Theory JP Jakonen Painosalama Oy, Turku, Finland 2020 Finland Turku, Oy, Painosalama ISBN 978-951-29-8251-6 (PRINT) – ISBN 978-951-29-8252-3 (PDF) TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS ISSN 0082-6987(Print) SARJA – SER. B OSA – TOM. 526 | HUMANIORA | TURKU 2020 ISSN 2343-3191 (Online) KEN WILBER AS A SPIRITUAL INNOVATOR Studies in Integral Theory JP Jakonen TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA – SER. B OSA – TOM. 526 | HUMANIORA | TURKU 2020 University of Turku Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Department of Study of Religion Doctoral Programme in History, Culture and Arts Studies (Juno) Supervised by Senior Lecturer Matti Kamppinen Adjunct Professor Ruth Illman University of Turku Åbo Akademi Reviewed by Professor Esa Saarinen University Lecturer Teuvo Laitila Aalto University University of Eastern Finland Opponent Professor Esa Saarinen Aalto University The originality of this publication has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. Cover photo and carving © Corey deVos Copyright © JP Jakonen, University of Turku ISBN 978-951-29-8251-6 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-8252-3 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987(Print) ISSN 2343-3191 (Online) Painosalama Oy, Turku, Finland 2020 UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Department of Study of Religion JP JAKONEN: Ken Wilber as a spiritual innovator. Studies in Integral Theory. Doctoral Dissertation, 173 pp. Doctoral Programme in History, Culture and Arts Studies (Juno) December 2020 ABSTRACT This dissertation studies the American philosopher Ken Wilber (1949–) through the lens of spiritual innovatorship. -

Big History in Its Cosmic Context

Big History in its Cosmic Context Joseph Voros Swinburne Business School Faculty of Business and Law Swinburne University of Technology Abstract Current models of Big History customarily take the observed increases over cosmic time of material-energetic complexity as their central concept. In this paper, we use Erich Jantsch’s pioneering masterwork The Self- Organizing Universe as the primary perspective from which to extend the customary ‘increasing material- energetic complexity’ view of Big History in two principal ‘directions’. Firstly, outwards, with an emphasis on increasing scale, scope and context to consider whether non-terrestrial analogues of Big History might exist or have existed elsewhere, and thus to embrace the ‘sibling’ multidisciplinary fields of SETI (the search for extra- terrestrial intelligence), Astrobiology, and ‘Cosmic Evolution’. And secondly, inwards, with a focus on (human) consciousness and the increasing complexity of human cognitive experience (‘interiority’) that has been apparent over the time-frame we have been able to observe it. Since Big History is a narrative which necessarily includes our own awakening to conscious awareness—and the felt sense of ‘meaning’ which our interiority brings with it—it would be valuable to examine related models which might also allow for an integration or unification of the two perspectives of physical-objective material-energetic complexity, on the one hand, and the complexity of subjective-conscious interiority, on the other. This is important, because it might provide a pathway that could help resolve recent debates around whether, and if so where, ‘meaning’ might reside in Big History. Current models do not tend to have a clear way to do this, so a particular integrative framework is introduced and outlined—due to the philosopher of consciousness Ken Wilber—which seeks to unify the customary complexity of matter-energy view of Big History with a ‘complexity of consciousness’ view, and which thereby suggests a very natural way to resolve the question of meaning ‘in’ Big History. -

Introduction

1 Introduction Consider that the [conflict] in which you find yourself is not the inconve- nient result of the existence of an opposing view but the expression of your own incompleteness taken as completeness; value the [conflict], miserable though it might feel, as an opportunity to live out your own multiplicity.1 “What!?” you may be saying to yourself, “I just paid good money for this book and you’re telling me to value my conflicts!? I’m trying to get rid of them, for crying out loud! This world has too damn many conflicts! What kind of nuts are you, anyway?” We will tell you, dear reader, that if you suspend your incredulity for the time that it takes to actually make your way through this book, you will find your thinking transformed about conflict. A brash and bold pronouncement, perhaps, but having seen how an All Quadrant All Level (AQAL)2 approach to conflict has transformed our own lives and work, we are confident that, at the very least, you will come away with a different understanding of conflict, and maybe even of yourself in conflict as well. A different understanding leads to a different response, and a different response can open the door to more and different possibilities, and more possibilities can include the recognition of our own evolving selves. That recognition alone—of our own evolving selves—opens up untold possibilities for understanding, engaging, and, yes, valuing conflict for its transformational potential. This book is our best effort at showing how. The two of us, Nancy and Richard, have been working together for many years—teaching, writing, and researching an AQAL approach to conflict. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

Holding Pattern' Succeeds with Classical Sounding Rock

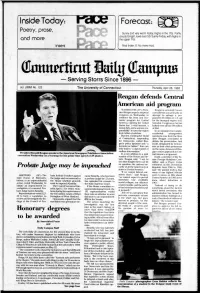

Inside Today: Forecast: Poetry, prose, Sunny and very warm today, highs in the 70s Partly cloudy tonight, lows near 50 Sunny Friday, with highs in and more the upper 70s insert Mud Index: 0. No more mud. Serving Storrs Since 1896 Vol. LXXXVI No. 122 The University of Connecticut Thursday, April 28, 1983 Reagan defends Central American aid program WASHING TON (AP (--Presi- Reagan's nationally broad- dent Reagan urged a skeptical cast address was primarily an Congress on Wednesday to- attempt to salvage a pro- embrace his arms and eco- posed $110 million in U5. aid nomic program for Central for the besieged regime in El America, claiming the United Salvador. Congress so far has States has "a vital interest, a balked over all but $30 million moral duty and a solemn res- of that. ponsibility" to save the region In an unusual if not unpre- from leftist revolution. cedented arrangement, But Sen. Christopher Dodd members rose from the floor of Connecticut, responding after Reagan concluded to for Democrats, called Rea- debate his presentation. And gan's policy ignorant and "a Dodd, designated by Democ- formula for failure" that can rats as their chief spokesman only lead to "a dark tunnel of on the issue, denounced Rea- endless intervention." gan's entire approach to Cen- President Ronald Reagan speaks to the American Newspaper Publishers Association In a rare address to a joint tral America as ignorant. convention Wednesday as a warmup for his prime time speech (UPI photo). session of the House and Se- Dodd. a member of the Se- nate, Reagan said, "I say to nate Foreign Relations Com- you that tonight there can be mittee and a Peace Corps no question: the national se- volunteer in the Dominican Probate Judge may be impeached curity of all the Americas is at Republic from 1966 to 1968. -

The Herbalist-Healer-Midwife-Witch in Contemporary English Novel

T.C. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Batı Dilleri ve Edebiyatları Anabilim Dalı İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı Bilim Dalı Doktora Tezi The Herbalist-Healer-Midwife-Witch in Contemporary English Novel Buket Akgün 2502040008 Tez Danı şmanı: Prof. Dr. Esra Meliko ğlu İstanbul, 10 Haziran 2011 ii ÖZ Bu tez, Atwood’un The Robber Bride ’ındaki (1993) Zenia ile Karen/Charis ve Chevalier’nin The Virgin Blue ’sundaki Isabelle’i (1997) erkeklerin belirledi ği sosyal, fiziksel, do ğa-do ğa üstü ve ya şam-ölüm snırlarını a ştıkları ve bu nedenle varlıkları ataerkil toplumun otoritesine ve düzenine tehdit olu şturdu ğu için ezilen ve cadılıkla yargılanan pek çok ebe ve kadın şifacının edebiyattaki altsoyları olarak incelemeyi amaçlamaktadır. Cadı olarak yaftalanan böyle güçlü kadınlar feminizmde kadın kimli ği ve söylemi olarak benimsenmektedir. Cadının altüst edici enerjisi yapısökücülük ve yapıbozumculuk yoluyla edebiyata ve postmodern söyleme akmaktadır. Bu çalı şmanın Giri ş bölümü cadıların tarih, edebiyat ve edebiyat kuramındaki erkeklerin belirledi ği ikili kar şıtlıkları altüst etmesine ayrılmı ştır. Birinci Bölüm Atwood’un The Robber Bride ’ında Zenia’yı, arkada şları Karen/Charis, Tony ve Roz’u kocalarının/partnerlerinin cinsel, fiziksel ve ekonomik sömürüsü ve eziyetinden kurtarıp, kadın dayanı şmasıyla yaralarını iyile ştirebilmelerine yardım eden özgürle ştirici bir güç olarak betimlemektedir. İkinci Bölüm, iyile ştirme/öldürme güçlerini anneannesinden miras alan, arkada şlarının Zenia’nın ba şlattı ğı özgürle şme sürecini atlatmalarına yardımcı olan ve sonunda Zenia’yı özgürle ştiren Karen/Charis üzerinde yoğunla şmaktadır. Üçüncü Bölümde Chevalier’nin The Virgin Blue ’sunda Isabelle’in ya şamı politik ve dini de ğişimlerin yansıması olarak tartı şılmaktadır; Isabelle herbalist-şifacı-ebe olması yüzünden damgalanır ve eziyet çeker. -

EV16 Inner DP

16 extreme voice JohnJJohnohn FoxxFoxx Exploring an Ocean of possibilities Extreme Voice 16 : Introduction All text and pictures © Extreme Voice 1997 except where stated. 1 Reproduction by permission only. have please. , g.uk . ears in My Eyes Cerise A. Reed [email protected] , oice Dancing with T obinhar r and eme V Extr hope you’ll like it! The Gift http://www.ultravox.org.uk , e ris, URL: has just been finished, and should be in the shops in June. EMAIL (ROBIN): Monument g.uk Rage In Eden enewal form will be enclosed. Cheques etc payable to (0117) 939 7078 We’ll be aiming for a Christmas issue, though of course this depends on news and events. We’ll Cerise Reed and Robin Har [email protected] UK £7.00 • EUROPE £8.00 • OUTSIDE EUROPE £11.00 as follows: It’s been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases and Internet websites, as you’ll been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases It’s TEL / FAX: THIS YEAR! 19 SALISBURY STREET, ST GEORGE, BRISTOL BS5 8EE ENGLAND STREET, 19 SALISBURY best! ”, and a yellow subscription r y eatment. At the time of writing EV16 EMAIL (CERISE): ry them, or at least be able to order them. So far ry them, or at least be able to order essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously unseen photographs, listen to messages from Midge unseen photographs, listen to messages from essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously ee in the following pages. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

The Creative Cosmos: a Personal Journey of Discovery

Network Review Summer 2009 21 articles The Creative Cosmos: A Personal Journey of Discovery Dr Erland Lagerroth Contemplating great works of fiction I found that the important points of view to apply were (inter)relation, wholeness, process, function, system – looking at the work not as a static phenomenon but as a dynamic process. At the same time an alternative science found the same for the world we live in. With interests on both sides I was more than happy to try to develop both these two fields. A Self-organising Universe of system or structure is a universal form of existence, but n my doctoral dissertation of 1958, Landscape and nobody seems to have understood it before Prigogine. Nature in (Selma Lagerlöf’s) Gösta Berling’s saga and What was wrong with materialism was not that it was a INils Holgersson I showed how parts of a literary work doctrine concerning matter but that it didn’t understand always have to be looked upon as interrelated, in my case matter. For what can be more obvious than the fact that the interrelations of landscape and nature to human beings and events – both epic relations on the causal level and nature organises itself. In the light of this we need to abandon lyrical relations on the level of similarities and contrasts. the idea of God as engineer and mechanic and understand Over the subsequent 50 years of professional life I have that man certainly does not arrange whirlpools in water and sought to reconcile the outlook of a literary humanist with air and other such phenomena. -

Regenerating Integral Theory and Education : Postconventional Explorations

Please do not remove this page Regenerating integral theory and education : postconventional explorations Hampson, Gary P https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/delivery/61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository/1266935420002368?l#1367448320002368 Hampson, G. P. (2010). Regenerating integral theory and education: postconventional explorations [Southern Cross University]. https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991012820881702368/61SCU_INST:Research Repository Southern Cross University Research Portal: https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/search?vid=61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository [email protected] Open Downloaded On 2021/09/27 11:37:52 +1000 Please do not remove this page REGENERATING INTEGRAL THEORY AND EDUCATION: Postconventional Explorations Gary P. Hampson REGENERATING INTEGRAL THEORY AND EDUCATION: Postconventional Explorations Gary P. Hampson Bachelor of Arts (Honours), Graduate Certificate (Strategic Foresight) A study submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Education Southern Cross University Australia February 2010 THESIS DECLARATION I certify that the work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text, and that the material has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other university. I acknowledge that I have read and understood the University’s rules, requirements, procedures and policy relating to my higher degree research award and to my thesis. I certify that I have been duly guided by the rules, requirements, procedures and policy of the University. Print Name:......................................................................................... Signature:………………………………………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………………………………………….. ABSTRACT This study seeks to facilitate the (re)generation of integral theory and integral education theory through exploring and enacting postconventional modalities emerging from worldviews and paradigms beyond modernity and formal thought. -

Excerpt A: an Integral Age at the Leading Edge

Excerpt A: An Integral Age at the Leading Edge Introduction Let us begin this overview by first noting what appears to be a rather dismal fact: today we hear a lot about Cultural Creatives and the new and exciting rise of an Integral Culture—a holistic, balanced, inclusive, caring culture that moves beyond the traditional and the modern and into a postmodern transformation. But, in fact, significant psychological evidence indicates that in today’s world, less than 2% of the population is at anything that could be called an “integral” wave of awareness (where “integral” means something like Gebser’s integral-aperspectival, Loevinger’s autonomous and integrated stages, Spiral Dynamics’ yellow and turquoise memes, Wade’s authentic, Arlin’s postformal, the centauric self and mature vision-logic, etc.). The same evidence suggests, however, that a very large percentage of the population— close to 25%—is at the immediately preceding wave of development (which is Loevinger’s individualistic stage, Spiral Dynamics’ green meme, Paul Ray’s cultural creatives, Wade’s affiliative, Sinnott’s relativistic, etc.). Moreover, because most of this population has been at the green-meme wave for several decades, it appears that a large portion—perhaps up to one-third— are ready to move forward to the next wave of expanding consciousness—which means, move forward to a truly integral wave of awareness. In other words, that modest 2% of the population that is now integral might soon swell to 5%, 10%, or more. I believe that, as with any evolutionary unfolding, we will especially start to see evidence of this increasingly integral consciousness at the growing tip, or at the leading edge, or in the avant garde (by whatever appellation)—in academia, the arts, social movements, Copyright © 2006 Ken Wilber. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri