Reproductiverights.Org…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slicreproductiverightsbook-Fifth Proof.Indd

CLAIMING DIGNITY: REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS & THE LAW Human Rights Law Network CLAIMING DIGNITY: REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS & THE LAW Human Rights Law Network Human Rights Law Network’s Vision • To protect fundamental human rights, increase access to basic resources for marginalised communities, and eliminate discrimination. • To Create a justice delivery system that is accessible, accountable, transparent, and effi cient and affordable, and works for the underpriviledged. • Raise the level of pro-bono legal experience for the poor to make the work uniformly competent as well as compassionate. • Professionally train a new generation of public interest lawyers and paralegals who are comfortable in the world of law as well as in social movements and who lean from such movements to refi ne legal concepts and strategies. CLAIMING DIGNITY: REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS & THE LAW Introduction by: Kerry McBroom Compiled and Edited by Cheryl Blake © Socio Legal Information Centre ISBN : 81-89479-84-9 January 2013 Design: Cover Photo Credit : Emily Schneider Cover Design : Karla Torres Printed by: Shivam Sundram Published by: Human Rights Law Network (HRLN) A division of Socio Legal Information Centre 576 Masjid Road, Jangpura New Delhi 110014 India Ph: +91-1124379855/56 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.hrln.org Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily the views of HRLN. Every effort has been made to avoid errors, ommissions, and innacuracies. HRLN takes sole responsibility for any remaining errors, ommissions or inaccuracies that may remain. Note on Footnote: The authors have employed a simple and straight-forward formatting style to maximize the usability of the sources cited. -

249TH Report of LAW COMMISSION of INDIA

249TH Report of LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA I. ENACTMENTS/PERMANENT ORDINANCES TO BE REPEALED BY PARLIAMENT S.No. Short title of the Act Subject Recommendation of Law Commission of India 1. Shore Nuisances Maritime Recommendation: Repeal (Bombay and Kolaba) Act, Law; 1853 (11 of 1853) Shipping and The Act facilitated the removal of Inland nuisances, obstructions and Navigation encroachments below high-water mark in the islands of Bombay and Kolaba for safe navigation in these harbours. The Collector was empowered, under this Act, to give notice for removal of any such nuisance from the sea-shore of the two islands. This is one of the earliest laws concerning water pollution and was meant to regulate the waste materials discharged in the coastal areas of Bombay and Kolaba, from various industries working in close vicinity of these areas. The management of hazardous waste materials is now carried out under various rules framed under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 and the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974. The purpose of this Act has been subsumed by later enactments. There is no evidence of this Act being in use. Hence, the Central Government should repeal this Act. This Act has also been recommended for repeal by the PC Jain Commission Report (Appendix A-5). 2. Tobacco Duty (Town of Taxes, Tolls Recommendation: Repeal Bombay) Act, 1857 (4 of and Cess 1857) Laws The Act amended the law relating to the duties payable on, and the retail sale and warehousing of tobacco, in the town of Bombay. The Act has now fallen into disuse. -

LAW COMMISSION of INDIA the Law

LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA The Law Commission of India is a non-statutory body constituted by the Government from time to time. The Commission was originally constituted in 1955 and is reconstituted every three years. The Twentieth Law Commission, i.e. the present one, has been constituted with effect from September 1, 2012 for a term of three years upto August 31, 2015. Justice Shri D. K. Jain was appointed as Chairman of 20th Law Commission of India w.e.f. 25th January 2013. However he resigned from the post of Chairman on 5th October 2013. Consequently, Mr. Justice A. P. Shah has been appointed as Chairman of the present Law Commissionw.e.f. 21st November, 2013. The present composition of the 20th Law Commission of India is as under:- S. No. Name Designation 1. Mr. Justice A.P. Shah, (Retd.) Former Chief Chairman Justice of the Delhi High Court. 2. Ms. Justice UshaMehra, (Retd.) Former Judge Full-time Member of the Delhi High Court 3. Mr. Justice S. N. Kapoor, (Retd.) Former Judge Full-time Member of the Delhi High Court 4. Prof. (Dr.) Mool Chand Sharma, Vice Full-time Member Chancellor, Central University of Haryana 5. Pro. (Dr.) YogeshTyagi, Dean & Professor of Part-time Member Law, South Asian University, New Delhi 6. Shri R. Venkataramani, Senior Advocate, Part-time Member Supreme Court of India 7. Dr. BijaiNarain Mani, Eminent law author Part-time Member 8. Dr. Gurjeet Singh, Director General of the Part-time Member National Law School & Judicial Academy Assam. The Terms of Reference of the Twentieth Law Commission are as under:- A. -

The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH

India HUMAN The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-735-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org February 2011 ISBN 1-56432-735-3 The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Map of India ............................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................. 2 Recommendations for Immediate Action by the Indian Government .................. 10 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 12 I. Recent Attacks Attributed to Islamist and Hindu Militant Groups ....................... -

GOVERNMENT of INDIA LAW COMMISSION of INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI Vis-À-Vis RIGHT to INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April, 2018 i ii Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 Table of Contents Chapters Title Pages I Background 1-23 A. A Brief History of Cricket in India 1 B. History of BCCI 3 C. Evolution of the Right to Information 5 (RTI) in India (a) Right to Information Laws in 9 States 1) Tamil Nadu 9 2) Goa 10 3) Madhya Pradesh 12 4) Rajasthan 13 5) Karnataka 14 6) Maharashtra 15 7) Delhi 16 8) Uttar Pradesh 17 9) Jammu & Kashmir 17 10) Assam 18 (b) RTI Movement – social and 19 national milieu II Reference to Commission and Reports 24-30 of Various Committees A. NCRWC Report, 2002 24 B. 179th Report of the Law Commission 26 of India, 2001 C. Report of the Pranab Mukherjee 26 Committee, 2001 D. Report of the Working Group for 27 Drafting of the National Sports Development Bill 2013 E. Lodha Committee Report, 2016 28 iii III Concept of State under Article 12 of the 31-36 Constitution of India - Analysis of the term ‘Other authorities’ IV RTI – Human Rights Perspective 37-55 a. Right to Information as a Human 38 Right - Constitutional position 40 b. Application to Private Entities 44 (i) State Responsibility 45 (ii) Duties of Private Bodies 46 c. Human Rights and Sports 48 V Perusal of the terms “Public Authority” 56-82 and “Public Functions” and “Substantially financed” 1. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

153 Thursday, the 6Th February, 2014

THURSDAY, THE 6TH FEBRUARY, 2014 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) @11-03 a.m. (The House adjourned at 11-03 and re-assembled at 12-00 Noon) 1. Starred Questions Answers to Starred Question Nos. 221 to 240 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 1649 to 1734 were laid on the Table. 12-00 Noon. 3. Papers Laid on the Table Dr. Girija Vyas (Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation) laid on the Table:- I. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub-section (1) of Section 619A of the Companies Act, 1956:- (i) (a) Sixtieth Annual Report and Accounts of the Hindustan Prefab Limited, New Delhi, for the year 2012-13, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts and the comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thereon. (b) Review by Government on the working of the above Company. (ii) (a) Forty-third Annual Report and Accounts of the Housing and Urban Development Corporation Limited (HUDCO), New Delhi, for the year 2012-13, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts and the comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thereon. (b) Review by Government on the working of the above Corporation. @ From 11-00 a.m. to 11-03 a.m., some points were raised. 153 RAJYA SABHA II. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (a) Annual Report and Accounts of the Building Materials and Technology Promotion Council (BMTPC), New Delhi, for the year 2012-13, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. -

FIGHT to Award Winner

MUSKAN SHOWS THE LIGHT INTERVIEWING DAWOOD LAWLESS LAW STUDENT Sightless youngster encourages youth How a journalist missed meeting the Don Colleges for education, not violence NOVEMBER 2017 `100 VOLUME I ISSUE 4 SPECIAL Lalu Prasad Yadav Vasundhara Raje Arvind Kejriwal Anil Baijal V K Sasikala Interview with Colin Gonsalves Right Livelihood FIGHT TO Award winner Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje’s safety valve Bill boomerangs; Delhi Chief MinisterTHE Arvind Kejriwal in last mile battleFINISH with Lieutenant-Governor in Supreme Court; and, Chief Justice of India wants a speedy trial of tainted netas LEGAL NOTES LEGAL NOTES ONE-ON-ONE ONE-ON-ONE placed, or innocent men put behind the bars in You have taken keen interest in legal battles the name of ‘love jihad’ or terrorism. ranging from the right to food to securing ‘Current phase in India’s history is as compensation for farmers and acid attack You are known to be a fighter for the rights of victims. the poor and the underprivileged for decades, It is my passion that keeps me moving forward dark as the Emergency’ setting many legal precedents in the process. despite resistance from various quarters. These The 65-year-old Senior Supreme Court Advocate Colin Gonsalves has been chosen for When did you start thinking of these people? movements take a big toll on an individual’s life. the prestigious 2017 Right Livelihood Award, widely known as ‘Alternative Nobel Prize’ I was a civil engineering student at the Indian For the Right to Food case, I went to the court Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay. -

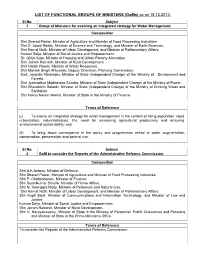

LIST of FUNCTIONAL GROUPS of MINISTERS (Goms) As on 18.12.2013

LIST OF FUNCTIONAL GROUPS OF MINISTERS (GoMs) as on 18.12.2013. Sl.No. Subject 1 Group of Ministers for evolving an integrated strategy for Water Management. Composition Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. Shri S. Jaipal Reddy, Minister of Science and Technology, and Minister of Earth Sciences. Shri Kamal Nath, Minister of Urban Development, and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. Kumari Selja, Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment. Dr. Girija Vyas, Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. Shri Jairam Ramesh, Minister of Rural Development. Shri Harish Rawat, Minister of Water Resources. Shri Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission. Smt. Jayanthi Natarajan, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. Shri Jyotiraditya Madhavrao Scindia, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Power. Shri Bharatsinh Solanki, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Shri Namo Narain Meena, Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance. Terms of Reference (i) To evolve an integrated strategy for water management in the context of rising population, rapid urbanization, industrialization, the need for increasing agricultural productivity and ensuring environmental sustainability; and (ii) To bring about convergence in the policy and programmes aimed at water augmentation, conservation, preservation and optimal use. Sl.No. Subjec t 2 GoM to consider the Reports of the Administrative Reforms Commission. Composition Shri A.K.Antony, Minister of Defence. Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. Shri P. Chidambaram, Minister of Finance. Shri Sushilkumar Shinde, Minister of Home Affairs. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 ADDRESSES Addresses at the Inaugural Function of the Seventh Meeting of Women Speakers of Parliament on Gender-Sensitive Parliaments, Central Hall, 3 October 2012 3 ARTICLE 14th Vice-Presidential Election 2012: An Experience— T.K. Viswanathan 12 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 17 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 22 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 26 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 28 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 30 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 43 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 45 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 49 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 62 Rajya Sabha 75 State Legislatures 83 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 85 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Twelfth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 227th Session of the Rajya Sabha 94 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2012 98 IV. -

2018, Four Senior Most Judges of the Supreme Court, Namely Justice

Rebellion in the Supreme Court By N.T.Ravindranath, dated 12-03-2018 On January 12th, 2018, four senior most judges of the Supreme Court, namely justice Chelameshwar, Ranjan Gogoi, Joseph Kurian and Madan Lokur stunned the people of India by openly revolting against the Chief Justice of India and conducting a press conference in Delhi accusing CJI Deepak Mishra of selective allocation of important cases for hearing to junior judges in an improper and inappropriate manner. Allocation of cases to different benches is the sole prerogative of the Chief Justice of India. Many important cases have been allocated to junior judges in the past and there is nothing unusual or unfair about it. The four dissident judges claim that all judges are equals and that the chief justice is only the first among the equals. On the other hand, contradicting their own assertion, they refuse to treat their own junior judges as their equals. Thus, their allegations against the chief justice Deepak Mishra can be seen as baseless and without any merit. Hence, the open mutiny staged by the four rebel judges is highly condemnable. This episode has not cast any shadow of doubt on the reputation and credibility of CJI Deepak Mishra. On the contrary, it is the four rebel judges who now stand exposed as crooks by their open expression of frustration and anger over non-allocation of certain cases of their interest to them. Their open revolt has only helped to expose their undue interest in getting certain cases allocated to them for their own vested interests which has raised questions about the impartiality and credibility of the Supreme Court. -

Securing the Independence of the Judiciary-The Indian Experience

SECURING THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY-THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE M. P. Singh* We have provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is difficult to suggest anything more to make the Supreme Court and the High Courts independent of the influence of the executive. There is an attempt made in the Constitutionto make even the lowerjudiciary independent of any outside or extraneous influence.' There can be no difference of opinion in the House that ourjudiciary must both be independent of the executive and must also be competent in itself And the question is how these two objects could be secured.' I. INTRODUCTION An independent judiciary is necessary for a free society and a constitutional democracy. It ensures the rule of law and realization of human rights and also the prosperity and stability of a society.3 The independence of the judiciary is normally assured through the constitution but it may also be assured through legislation, conventions, and other suitable norms and practices. Following the Constitution of the United States, almost all constitutions lay down at least the foundations, if not the entire edifices, of an * Professor of Law, University of Delhi, India. The author was a Visiting Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law, Heidelberg, Germany. I am grateful to the University of Delhi for granting me leave and to the Max Planck Institute for giving me the research fellowship and excellent facilities to work. I am also grateful to Dieter Conrad, Jill Cottrell, K. I. Vibute, and Rahamatullah Khan for their comments.