BUILDING INTEGRITY SINCE 1890 the Remarkable History of Sundt Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Room, Buy Your Monthly Commuting Pass, Donate to Your Favorite Charity…Whatever Moves You Most

Sun Devil families celebrate university connections ASU leads space exploration efforts Business school breaks new ground THEMAGAZINEOFARIZONASTATEUNIVERSITYmaroon and gold memoriesHonoring and adapting ASU traditions MARCH 2012 | VOL. 15, NO. 3 IMAGINE WHAT YOU COULD DO WITH YOUR SPECIAL SAVINGS ON AUTO INSURANCE. Upgrade to an ocean view room, buy your monthly commuting pass, donate to your favorite charity…whatever moves you most. As an ASU alum, you could save up to $343.90 safer, more secure lives for more than 95 years. Responsibility. What’s your policy? CONTACT US TODAY TO START SAVING CALL 1-888-674-5644 Client #9697 CLICK LibertyMutual.com/asualumni AUTO COME IN to your local offi ce This organization receives fi nancial support for allowing Liberty Mutual to offer this auto and home insurance program. *Discounts are available where state laws and regulations allow, and may vary by state. To the extent permitted by law, applicants are individually underwritten; not all applicants may qualify. Savings fi gure based on a February 2011 sample of auto policyholder savings when comparing their former premium with those of Liberty Mutual’s group auto and home program. Individual premiums and savings will vary. Coverage provided and underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance Company and its affi liates, 175 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA. © 2011 Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. All rights reserved. The official publication of Arizona State University Vol. 15, No. 3 Scan this QR code President’s Letter to view the digital magazine Of all the roles that the ASU Alumni Association plays as an organization, perhaps none is more important than that PUBLISHER Christine K. -

Arizona State University June 30, 2005 Financial Report

2005 FINANCIAL REPORT On the front cover Clockwise from the top – In August 2004 ASU welcomed 58,156 students to its campuses. Included were 162 National Merit Scholars and over 7,700 fi rst time freshmen. More than 27% of the fi rst time freshmen on the campuses were rated in the top 10% of their high school graduating classes. During the past 11 years ASU has had more students than any other public university selected for the USA Today’s ranking of the nation’s top 20 undergraduates. When compared against private universities, ASU ranks 3rd overall in students selected for this ranking. ASU’s student population represents all 50 states and more than 140 nations. As a part of the University’s initiatives to enhance the freshmen classroom experience, the average class size of core freshmen classes, such as English composition and college algebra courses, has been reduced. ASU’s Barrett Honors College is considered among the top honors colleges in the nation and selectively recruits academically outstanding undergraduates. In the 2004/2005 academic year ASU had one of the largest classes of freshmen National Merit Scholars of any public university. ASU is committed to community outreach through its schools and colleges, non academic departments, and student organizations. Often these programs involve interaction with local schools or neighborhoods. Programs include helping American Indian students who have an interest in health care programs explore those interests in the nursing, math, and science fi elds; exposing the children of migrant farm workers to various technology programs and equipment; providing professional development resources to Arizona’s K 12 teachers through a web portal; and preparing minority engineering students for the college experience. -

Your Future Campus

Published October 2016. XX. Photo credit: Scott Troyanos. 2694 Troyanos. Scott credit: Photo XX. 2016. October Published alternative formats, contact Admission Services at 480-965-7788 or fax 480-965-3610. 480-965-3610. fax or 480-965-7788 at Services Admission contact formats, alternative Information is subject to change. © 2014 ABOR for ASU. To request this publication in in publication this request To ASU. for ABOR 2014 © change. to subject is Information @FutureSunDevils @FutureSunDevils instagram.com download the ASU app ASU the download @FutureSunDevils /FutureSunDevils twitter.com facebook.com Connect with us: us: with Connect Tempe campus | Self-guided tour Self-guided | campus Tempe asu.edu/apply asu.edu/mydegree campus Apply for admission admission for Apply degrees Explore Sun Devil journey journey Devil Sun future Your Take the next step on your your on step next the Take Join us Join ASU has emerged as a leader in higher education. Nationally recognized by The Wall Street Journal for preparing the most-qualified college graduates, it consistently ranks as the top ASU rankings school in Arizona for innovation, affordability, quality of students and academic programs. title source AZ ranking U.S. ranking best bang for the buck Washington Monthly 1 24 best-qualified graduates The Wall Street Journal 1 5 top scholars Fulbright Scholar Awards 1 5 most innovative U.S. News & World Report 1 1 public good Washington Monthly 1 34 best colleges for the money Fox Business 1 Top 10 international choice Institute of International Education 1 4 best graduate education school U.S. News & World Report 1 14 best colleges for veterans College Factual 1 2 1st St Welcome to Arizona State University’se Tempe campus v A Rio Salado Pwky Maple 2nd St 1 College Ave. -

Historic Properties Treatment Plan for Monitoring and Phased Data

Historic Properties Treatment Plan for Monitoring and Phased Data Recovery at AZ U:9:165(ASM) for the 8th Street Multi-use Path and Streetscape Improvements (Rural Road to McClintock Drive), Tempe, Maricopa County, Arizona Prepared for: City of Tempe Prepared by: Sara C. Ferland Submitted by: Mark Hackbarth, M.A., RPA 51 West Third Street, Suite 450 Tempe, AZ 85281 April 2018 (Submittal 2) Logan Simpson Technical Report No. 175186b ABSTRACT AND MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Report Title Historic Properties Treatment Plan for Monitoring and Phased Data Recovery at AZ U:9:165(ASM) for the 8th Street Multi-use Path and Streetscape Improvements (Rural Road to McClintock Drive), Tempe, Maricopa County, Arizona Report Date April 4, 2018 (Submittal 2) Agencies Involved Federal Highways Administration (FHWA), Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT), State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), Arizona State Museum (ASM), City of Tempe (COT) Land Ownership COT Funding Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program though the FHWA ASM Permits Arizona Antiquities Act project-specific permit (to be obtained) Burial Agreement, in accordance with A.R.S. §41-844 (to be obtained) Repository A Curation Agreement will be obtained from the Tempe History Museum Logan Simpson 175186 Project No. Project Description The COT, in conjunction with the ADOT and FHWA, is planning to construct a multi-use path (MUP) and streetscape improvement project along 8th Street between Rural Road and McClintock Drive in Tempe. The area of potential effects (APE) consists of approximately one mile of the existing 73.0 ft to 90.5 ft. This includes the COT-owned property on the north side of 8th Street from Rural Road to Dorsey Lane (a former railroad ROW measuring 33 feet wide by 2,640 feet long), and a Salt River Project easement at the southeast corner of 8th Street and Rural Road. -

April 19, 2017 REQUEST for PROPOSAL UNARMED

April 19, 2017 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL UNARMED SECURITY GUARD SERVICES RFP 341707 DUE: 3:00 P.M., MST, 05/12/17 Time and Date of Pre-Proposal Conference 8:30 A.M., MST, 04/24/17 Deadline for Inquiries 5:00 P.M., MST, 04/28/17 Time and Date Set for Closing 3:00 P.M., MST, 05/12/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE SECTION I – REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL .................................................................... 4 SECTION II – PURPOSE OF THE RFP .......................................................................... 5 SECTION III – PRE-PROPOSAL CONFERENCE .......................................................... 9 SECTION IV – INSTRUCTIONS TO PROPOSERS ...................................................... 10 SECTION V – SPECIFICATIONS/SCOPE OF WORK .................................................. 17 SECTION VII – PROPOSER QUALIFICATIONS .......................................................... 26 SECTION VIII – EVALUATION CRITERIA ................................................................... 28 SECTION IX – PRICING SCHEDULE ........................................................................... 29 SECTION X – FORM OF PROPOSAL/SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS ............................. 31 SECTION XI – PROPOSER INQUIRY FORM ............................................................... 32 SECTION XII – TERMS & CONDITIONS ...................................................................... 33 SECTION XIII – MANDATORY CERTIFICATIONS ...................................................... 44 APPENDIX A - ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY POLICE -

To Download the Conference Program

PROGRAM & VISITORS GUIDE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON URBANIZATION AND GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE Opportunities & Challenges for Sustainability in an Urbanizing World ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY TEMPE, ARIZONA, USA OCTOBER 15-17, 2010 Welcome! Dear conference participants, We welcome you to the first International Conference on Urbanization and Global Environmental Change, Opportunities and Challenges for Sustainability in an Urbanizing World. Over the last five years, the Urbanization and Global Environmental Change (UGEC) community has grown rapidly and generated new understandings of the relationships between urbanization and the global environment. This conference is an exciting opportunity to bring together communities of academics, decision- makers, and practitioners at local, regional, and global scales in order to take stock of UGEC science and practice. Conference participants come from 40 countries and presentation topics range from the role of higher education as a catalyst for sustainability to urban vegetation, and socio-ecological contexts for urban sustainability. We have also included special sessions such as the one on the 2014 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report and UGEC research. We want to encourage interactions and dialogue between the participants during plenaries, parallel sessions and breaks; we clearly recognize the added-value of providing such opportunities and have designed our conference structure accordingly. On Saturday, October 17th, we will hold a joint-conference day with the IHDP Global Land Project, under the theme, “Sustainable Land Systems in the Era of Urbanization and Climate Change.” The goal of this day is to strengthen existing relationships and build new networks among urban and land- change specialists to foster more collaboration worldwide, expanding the range of issues addressed. -

Arizona Board of Regents Past President, Navajo Nation Olympian, Track & Field Security and Non-Proliferation, U.S

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Arizona State University is one of the premier metro- politan public research universities in the nation. Enrolling more than 64,000 undergraduate, graduate, and profes- sional students on four campuses in metropolitan Phoenix, ASU maintains a tradition of academic excellence in core disciplines, and has become an important global center for innovative interdisciplinary teaching and research. Arizona State offers outstanding resources for study and research, including libraries and museums with important collections, studios and performing arts spaces for creative endeavor, and unsurpassed state-of-the-art scientific and technological laboratories and research facilities. ASU’s historic campus in Tempe, which serves more than 51,000 students, offers the feel of a college town in the midst of a dynamic metropolitan region. The West campus, in northwest Phoenix, and Polytechnic campus, in Mesa, which each serve more than 8,500 students, offer more specialized missions. The Downtown Phoenix campus opened in fall 2006 as part of a larger plan to revitalize the city’s urban core. Nestled in the heart of downtown Phoenix, the campus provides an academically rigorous university experience in a modern, urban atmosphere. The campus serves more than 6,500 students and is expected to ultimately grow to 15,000 by 2020. ASU is research-driven but focused on learning – the United States. ASU has the most undergraduates (11) The university is international in scope, welcoming teaching is carried out in a context that encourages the named to USA Today’s Academic First Team of any public students from all 50 states and nations across the globe, creation of new knowledge. -

General Information

GENERAL INFORMATION General Information Arizona State University has emerged as a leading The regents select and appoint the president of the univer- national and international research and teaching institution. sity, who is the liaison between the Arizona Board of Located in the Phoenix metropolitan area, this rapidly grow- Regents and the institution. The president is aided in the ing, multicampus public research university offers programs administrative work of the institution by the provosts, vice from the baccalaureate through the doctorate for approxi- presidents, deans, directors, department chairs, faculty, and mately 58,156 full-time and part-time students through ASU other officers. Refer to “Tempe Campus Administrative Per- at the Tempe campus; the West campus in northwest Phoe- sonnel,” page 680. nix; a major educational center in downtown Phoenix; the The academic units develop and implement the teaching, East campus, located at the Williams Campus (formerly research, and service programs of the university, aided by Williams Air Force Base) in southeast Mesa; and other the university libraries, museums, and other services. instructional, research, and public service sites throughout The faculty and students of the university play an impor- Maricopa County. See the “Fall 2004 Enrollment” table tant role in educational policy, with an Academic Senate, below. joint university committees and boards, and the Associated Students serving the needs of a large institution. Fall 2004 Enrollment ACADEMIC ACCREDITATION AND AFFILIATION Type Students See “Accreditation and Affiliation,” page 712. Total 58,156 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY AND AFFIRMATIVE East campus 3,983 ACTION Tempe campus 49,171 It is the policy of ASU to provide equal opportunity West campus 7,348 through affirmative action in employment and educational National Merit Scholars (incoming freshmen) 162 programs and activities. -

COVID: Finding Answers in Arizona

COVID: Finding Answers in Arizona Arizona Wellbeing Commons 2020 Friday, October 9, 2020 9:00 a.m. – 3:15 p.m. Over the past several months, Arizona’s research, medical and public health professionals have stepped up to the plate like never before. The arrival of the SARS- CoV-2 virus called on us to respond to a wide variety of challenges. For many of us, it meant pivoting away from our day-to-day responsibilities in order to respond to the demands of the day. By most accounts, it appears that we have delivered. Unfortunately, the battle is not over. Certainly, the goal of the Arizona Wellbeing Commons is more meaningful than ever: To work together to improve the health and wellbeing of the people of Arizona. Join us today as we make new connections, share new ideas and pursue new initiatives. NOTE: This webinar event is a live broadcast. Real event times may differ slightly from what is indicated on the agenda. Event agenda Welcome 9:00 a.m. Hosts: Josh LaBaer, Exec Dir, Biodesign Institute & Jude LaCava, Bioscience advocate Larry Edward Penley, Chair, Arizona Board of Regents Keynote address The Covid-19 Pandemic: What have we learned thus far? Tara O’Toole, Exec Vice President and Senior Fellow, In-Q-Tel From where I sit: A conversation with Dr. Tara O’Toole 9:15 a.m. George Poste, Chief Scientist, Complex Adaptive Systems, ASU It’s your turn: Share your ideas, questions and concerns Information is Power: A video tribute to the Pandemic Modeling Team Arizona State University, University of Arizona, Northern Arizona University About the Arizona Wellbeing Commons 10:20 a.m. -

Self-Guided Tour of the Tempe Campus

self-guided tour of the tempe campus “Sustainability is larger than one person, one company, or one country. Its scope, scale, and importance demand unprecedented and swift solutions to environmental protection and other complex problems.” — Julie Ann Wrigley, co-founder, Global Institute of Sustainability and School of Sustainability Welcome to Arizona State University We invite you to discover and explore some of the exciting sustainability initiatives and projects here at ASU. By following this 1.2-mile walking tour you will see LEED*-certified buildings, solar installations, and a variety of examples that comprise our integrated, university-wide approach to sustainability at ASU – a combination of small steps and bold moves! Learn more at: asu.edu/tour/sustainability *Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) is an internationally recognized green building certification system, providing third-party verification that a building or community was designed and built using strategies intended to improve performance in metrics such as energy savings, water efficiency, CO2 emissions reduction, improved indoor environmental quality, and stewardship of resources and sensitivity to their impacts. Memorial Union Farmers Market: During the fall and spring semesters the The second floor of the Memorial Union was renovated in 2008; Tempe Campus Farmers Market features 20+ vendors with fresh sustainability features include 30 percent regionally extracted or produce grown by local Arizona farmers and other local products. manufactured materials and “EcoSystem” lighting that reduces energy The Farmers Market promotes healthy eating and sustainability costs by 70 percent. Over half of the construction waste was recycled. among students, faculty, and staff. Sustainable Design Standards: Since 2005, all new university- EVENT GREEN owned buildings are required to be certified LEED Silver or higher. -

Growing Infrastructure Creates New Research Space for Fulton School

FULLEngineering, Construction, CIRCLE and Computer Science News for Friends and Alumni of Arizona State University Fall 2005 Feature Stories Growing Infrastructure Creates New Research In This Issue Space for Fulton School New Fulton Fellowship Program Attracts Graduate Students Global Engagement Begins with Mexico Curriculum Redesign Provides Foundation for Tomorrow’s Fulton Engineer High-Performance Computing Facility Opens at ASU Show Your Fulton School Pride Men’s clothing Women’s clothing Head wear PrideThe Fulton School of Engineering is building a world-class institution with high-quality graduates, dynamic research and a rising reputation. Get recognized as an alumnus of the Fulton School today. The online store has a number of ways you can show your pride, choose from a great selection of shirts, hats and gifts. Log on to: Business accessories www.fulton.asu.edu/merchandise Small gifts commentscocommmm Contents CROUCH’S The Fulton School of Engineering School News . 2 is rife with energy and expectation Leveraging Space at ASU . .4 as we expand and emerge on many Global Engagement with Mexico . .8 fronts. Our capacity for research is Student News . 12 increasing, while our relationships Fulton Fellows . .12 with international neighbors continue Ph.D. Students Experience Real World . .15 to thrive. Our educational programs Curriculum Redesign . .16 are being transformed and new ones Alumni News . 18 implemented. And, we celebrate the In Practice . .18 successes of our alumni, welcom- Fulton Alumnus Returns to ASU . .21 ing back those graduates who have Where are they now? . .22 returned to be a part of ASU. Discovery News . 24 High Performance Computing . -

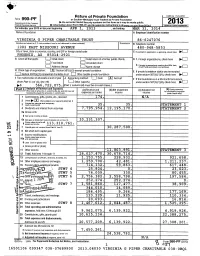

990-PF Return of Private Foundation May,=A

^r3 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation enter Social Department of the Treasury ► Do not Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Internal Revenue seance ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate Instructions is at rin ulfn For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning APR 1, 2013 , and ending MAR 31 , 2014 Name of foundation A Employer identification number VIRGINIA G PIPER CHARITABLE TRUST 86-6247076 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 1202 EAST MISSOURI AVENUE 480-948-5853 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal C code If exemption application is pending, check here ► PHOENIX, AZ 85014-2921 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return 0 Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, D Address chang e D Name change check here and attach computation H Check type organization: X of Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 (a)( 1 ) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► 0 I Fair market value of all assets end at of year J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part I!, co! (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here 5 6 6 , 7 2 2 , 0 7 5 .