Excellence V Equity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spoons Is Opening a Pub in Headingley and We Are So Here for It

https://thetab.com/uk/leeds/2019/11/09/spoons-is-opening-a-pub-in-headingley-and-we-are-so- here-for-it-49428 Spoons is opening a pub in Headingley and we are so here for it A new addition to the Otley Run? 2 months ago Matt Livingstone Wetherspoons have received permission to open a new pub on Headingley Lane, halfway between The Original Oak and Hyde Park Book Club. We've been crying out for a spoons in Headingley for ages, and it seems like our prayers have finally been answered. Spoons bought the building, which used to be an old Girls High School, four years ago, but boring residents postponed any plans with complaints. But now, the new Spoons has finally got the go ahead, and we can't wait to make it our new local for post-uni drinks. We've always got time for a pitcher or seven There's no official opening date yet, but we'll keep you in the loop with any developments because arguably this is the most important change happening in the whole of the city. Matt Livingstone Life LEEDS We are the voice of students. The Tab is a site covering youth culture and student culture, run by journalists who like being first. We livestream from protests, expose bullshit and discrimination and tell you which kebab shops are worth your money. Our London office is run by 23-year-olds, who write seriously hot takes, sickeningly accurate guides to life, and chat to Jeremy Corbyn about Love Island. The Tab Network – our guerilla army of bold and subversive student reporters across the country – breaks stories like this lovely young man who burned a £20 note in front of a homeless man We were founded by three students at Cambridge in 2009 as a reaction to out- oftouch student papers. -

7Th Abu Dhabi-Singapore Joint Forum Continues to Provide Platform for Strengthening of Bilateral Ties Relationship Sees Progre

7th Abu Dhabi-Singapore Joint Forum Continues to Provide Platform for Strengthening of Bilateral Ties Relationship Sees Progress in Key Areas of Collaboration MR No.: 047/13 Singapore, 26 November 2013 – The 7th Abu Dhabi-Singapore Joint Forum (ADSJF) was held in Singapore today under the co-chairmanship of Mr Lee Yi Shyan, Singapore’s Senior Minister of State for Trade & Industry and National Development, and His Excellency Khaldoon Al Mubarak, Chairman of the Executive Affairs Authority of Abu Dhabi. The Forum, jointly organised by International Enterprise (IE) Singapore and the Abu Dhabi Executive Affairs Authority (EAA) convened approximately 60 government and business representatives from both Abu Dhabi and Singapore, reflects the ongoing and effective growth in the bilateral relationship between the two governments. Said Mr Lee Yi Shyan, Singapore Co-Chair of the ADSJF and Senior Minister of State for Trade & Industry and National Development, “The Abu Dhabi-Singapore Joint Forum has achieved much since 2007. The number of Singapore companies in the UAE has risen from 90 to 130. These companies have made significant investments in the UAE as well. For instance, Sembcorp recently invested US$80 million to expand its sea desalination capacity in the UAE. We look forward to continuing our close cooperation in the future. Said H.E. Khaldoon Al Mubarak, Abu Dhabi Co-Chair of the ADSJF and Chairman of the Abu Dhabi Executive Affairs Authority, “We have been convening these meetings for many years now, and a lot has been achieved in that time - in areas as diverse as transportation, urban development, technology and the energy sector. -

Premier League, 2018–2019

Premier League, 2018–2019 “The Premier League is one of the most difficult in the world. There's five, six, or seven clubs that can be the champions. Only one can win, and all the others are disappointed and live in the middle of disaster.” —Jurgen Klopp Hello Delegates! My name is Matthew McDermut and I will be directing the Premier League during WUMUNS 2018. I grew up in Tenafly, New Jersey, a town not far from New York City. I am currently in my junior year at Washington University, where I am studying psychology within the pre-med track. This is my third year involved in Model UN at college and my first time directing. Ever since I was a kid I have been a huge soccer fan; I’ve often dreamed of coaching a real Premier League team someday. I cannot wait to see how this committee plays out. In this committee, each of you will be taking the helm of an English Football team at the beginning of the 2018-2019 season. Your mission is simple: climb to the top of the world’s most prestigious football league, managing cutthroat competition on and off the pitch, all while debating pressing topics that face the Premier League today. Some of the main issues you will be discussing are player and fan safety, competition with the world’s other top leagues, new rules and regulations, and many more. If you have any questions regarding how the committee will run or how to prepare feel free to email me at [email protected]. -

Dollars and Decadence Making Sense of the US-UAE Relationship

Dollars and Decadence Making Sense of the US-UAE Relationship Colin Powers April 2021 Noria Research Noria Research is an independent and non-profit research organization with roots in academia. Our primary mandates are to translate data gathered on the ground into original analyses, and to leverage our research for the purpose of informing policy debates and engaging wider audiences. It is our institutional belief that political crises cannot be understood without a deep grasp for the dynamics on the ground. This is why we are doctrinally committed to field-based research. Cognizant that knowledge ought to benefit society, we also pledge to positively impact civil society organizations, policymakers, and the general public. Created in Paris in 2011, Noria’s research operations now cover the Americas, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. Licence Noria Research encourages the use and dissemination of this publication. Under the cc-by-nc-nd licence, you are free to share copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. Under the following terms, you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material. Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of Noria Research. Author: Colin Powers Program Director: Robin Beaumont Program Editor: Xavier Guignard Graphic Design: Romain Lamy & Valentin Bigel Dollars and Decadence Making Sense of the US-UAE Relationship Colin Powers April 2021 About Middle East and North Africa Program Our research efforts are oriented by the counter-revolution that swept the Middle East and North Africa in the aftermath of 2011. -

Resuming Previously Upwand Momentum

Business & Finance Weekly WORLD June 15-19.2020 Issue 07 MSCI WORLD INDEX 2.06% ▲ MAJOR 1.15 % 1.04 % 1.86 % 3.73 % 1.62 % 1.64 % 0.78 % 2.72 % 3.19 % 3.07 % INDICES JSE/Top40 DJIA S&P500 NASDAQ ASX200 SSECOMP NIKKEI225 NIFTY50 DAX FTSE100 MARKETS REVIEW Week June 15-19 KEY POINTS Resuming previously upwand momentum FDI ollowin ga bruis - the Bank of Japan (BoJ), kept its mon - ing decline the etary policy largely unchanged and de - previous week , cided to boost financing support for Global foreign direct in - world markets re - hard-hit companies beyond $1 trillion. vestment (FDI) flows bounded sharply. Chinese markets were also higher this are forecast to decrease ●CHINA-INDIA :On Monday, 20 Indian soldiers Kyriaki The biggest catalysts week with the domestic large-cap CSI by up to 40% in 2020, were killed in physical fights with Chinese troops I.Balkoud were the Fed’s deci - 300 index outpacing the benchmark from their 2019 value of in a disputed Himalayan border area, Indian officials Editor sion to increase its Shanghai Composite. In Australia, the $1.54 trillion, according said. The incident follows rising tensions. It was the support and the news that the White ASX200 index managed to add 1.62 to UNCTAD’s World In - deadliest clash between the neighbours in decades. House is working on a massive stim - per cent for the week. vestment Report 2020. ulus plan focused on infrastructure in - (See Asia/Pacific on p.4) vestment. Sentiment also got a lift EUROPE: European equities ended from upbeat economic data. -

U.S. Universities Rush to Set up Outposts Abroad

U.S. Universities Rush to Set Up Outposts Abroad THE NEW YORK TIMES February 10, 2008 Global Classrooms By TAMAR LEWIN When John Sexton, the president of New York University, first met Omar Saif Ghobash, an investor trying to entice him to open a branch campus in the United Arab Emirates, Mr. Sexton was not sure what to make of the proposal — so he asked for a $50 million gift. “It’s like earnest money: if you’re a $50 million donor, I’ll take you seriously,” Mr. Sexton said. “It’s a way to test their bona fides.” In the end, the money materialized from the government of Abu Dhabi, one of the seven emirates. Mr. Sexton has long been committed to building N.Y.U.’s international presence, increasing study-abroad sites, opening programs in Singapore, and exploring new partnerships in France. But the plans for a comprehensive liberal-arts branch campus in the Persian Gulf, set to open in 2010, are in a class by themselves, and Mr. Sexton is already talking about the flow of professors and students he envisions between New York and Abu Dhabi. The American system of higher education, long the envy of the world, is becoming an important export as more universities take their programs overseas. In a kind of educational gold rush, American universities are competing to set up outposts in countries with limited higher education opportunities. American universities — not to mention Australian and British ones, which also offer instruction in English, the lingua franca of academia — are starting, or expanding, hundreds of programs and partnerships in booming markets like China, India and Singapore. -

Planning Abu Dhabi: from Arish Village to a Global, Sustainable, Arab Capital City by Alamira Reem Bani Hashim a Dissertation S

Planning Abu Dhabi: From Arish Village to a Global, Sustainable, Arab Capital City By Alamira Reem Bani Hashim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elizabeth S. Macdonald, Chair Professor Michael Southworth Professor Greig Crysler Summer 2015 © Alamira Reem Bani Hashim Abstract Planning Abu Dhabi: From Arish Village to a Global, Sustainable Arab Capital City by Alamira Reem Bani Hashim Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Elizabeth S. Macdonald, Chair The overarching objective of this research project is to explore and document the urban history of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. It is organized as a comparative study of urban planning and design processes in Abu Dhabi during three major periods of the city’s development following the discovery of oil: (1) 1960-1966: Sheikh Shakhbut Bin Sultan Al Nahyan’s rule (2) 1966-2004: Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan’s rule; and (3) 2004-2013: Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s rule. The intention of this study is to go beyond a typical historical narrative of sleepy village-turned-metropolis, to compare and contrast the different visions of each ruler and his approach to development; to investigate the role and influence of a complex network of actors, including planning institutions, architects, developers, construction companies and various government agencies; to examine the emergence and use of comprehensive development plans and the policies and values underlying them; as well as to understand the decision-making processes and design philosophies informing urban planning, in relation to the political and economic context of each period. -

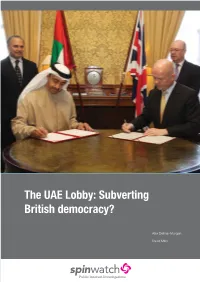

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British Democracy?

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British democracy? Alex Delmar-Morgan David Miller ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHORS Thanks to the Arab Organisation for Human Alex Delmar-Morgan Rights for its financial support for this report. is a freelance journalist in London and has written Thanks also to all those who have shared for a range of national titles information with us about or related to the UAE including The Guardian, lobby. We are indebted to a wide variety of people The Daily Telegraph, and who have shared stories and information with us, The Independent. He is the most of whom must remain nameless. We also former Qatar and Bahrain correspondent for thank Hilary Aked, Izzy Gill, Tom Griffin, Tom Mills. the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones. On a personal note, thanks to Narzanin Massoumi for her many contributions to this work. David Miller is a director of Public Interest Investigations, of which Spinwatch.org and CONFLICT OF INTEREST Powerbase.info are projects. He STATEMENT is also Professor of Sociology at the University of Bath in No external person had any role in the study, England. From 2013-2016 design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of he was RCUK Global Uncertainties Leadership data, or writing of the report. For the transparency Fellow leading a project on Understanding and policy of Public Interest Investigations and a list of explaining terrorism expertise in practice. grants received see: http://www.spinwatch.org/ index.php/about/funding Recent publications include: • The Quilliam Foundation: How ‘counter- PUBLIC INTEREST extremism’ works, (co-author, Public interest INVESTIGATIONS Investigations, 2018); • Islamophobia in Europe: counter-extremism Public Interest Investigations (PII) is an policies and the counterjihad movement, independent non-profit making organisation. -

Here Singapore Companies Have Established Themselves in the Energy, Water, Urban Solutions, and Consumer Sectors

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release ABU DHABI AND SINGAPORE TO EXPLORE POTENTIAL AREAS OF COOPERATION AT THE 12TH ABU DHABI-SINGAPORE JOINT FORUM 1. Minister-in-charge of Trade Relations S Iswaran will be in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE) from 13 to 14 November 2019. While in Abu Dhabi, Mr Iswaran will co-chair the 12th Abu Dhabi-Singapore Joint Forum (ADSJF) with Chairman of the Executive Affairs Authority (EAA) of Abu Dhabi H.E. Khaldoon Al Mubarak on 14 November 2019. 2. During the forum, Mr Iswaran will reaffirm the bilateral links between the UAE and Singapore, and highlight the wide-ranging business interests in the UAE especially in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where Singapore companies have established themselves in the energy, water, urban solutions, and consumer sectors. 3. Mr Iswaran and H.E. Khaldoon are also expected to discuss ways to deepen bilateral engagement through connecting the Singapore and Abu Dhabi start-up ecosystem, furthering collaboration between Singapore’s and Abu Dhabi’s space industries, and developing partnerships on innovation with UAE’s large enterprises, such as GlobalFoundries and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. 4. Mr Iswaran said, “We have strengthened our bilateral ties with Abu Dhabi since the 1st ADSJF in 2007. As the global economy shifts towards innovation and digitalisation, we hope that our bilateral cooperation will similarly incorporate new areas of collaboration such as the digital economy. This will ensure continued relevance as both our economies adapt and move ahead in the global state-of-play.” 5. During the visit, Mr Iswaran will also be meeting with UAE Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence Omar Bin Sultan Al Olama and Chairman of the Abu Dhabi Executive Council Sheikh Khalid Bin Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan. -

The Official Ferrari Opus “With Pininfarina He Made Only Beautiful Cars

The official ferrari OpuS “With Pininfarina he made only beautiful cars. Sergio Scaglietti used to tell him: ‘You’ve got to make cars beautiful, because making them beautiful or ugly costs the same.’ Dad always placed a lot of importance on style, believing in a winning formula that still works today” From ‘My Father, Enzo Ferrari’, an interview with Piero Ferrari for The Official Ferrari Opus “ferrari is the best spokesperson for italian car design because it represents our values in full: a particular way of seeing life, the ability to achieve excellent results without renouncing beauty, brilliance or extroversion” From ‘The Perfect Body’ by Lorenzo Ramaciotti, former style director of Pininfarina, for The Official Ferrari Opus A unique combination of technical flair, Italian style In the quest to create the ultimate publication on Ferrari, and elegance, mystique and an unquenchable thirst for Opus has scoured private and public picture archives perfection has made Ferrari the most desirable automobile around the world to select over 1,000 unique, rare or brand in the world. The Official Ferrari Opus is the ultimate previously unpublished photographs. celebration of the Prancing Horse and the company’s continuing success, both on the race track and on the road. Many exclusive photo shoots have been commissioned for The Official Ferrari Opus, featuring key Ferrari personalities Whether it’s behind the scenes with the workers at the such as Luca di Montezemolo, Piero Ferrari, Niki Lauda and legendary factory in Maranello, at the races with the F1 team Jean Todt, as well as a unique photo essay by Rankin, one or in the cockpit with the drivers, The Official Ferrari Opus of the world’s foremost photographers, on the iconic 1961 offers an unprecedented insight into the magic of Ferrari. -

City Football Group Signals China Growth As CMC Holdings Led Consortium Acquires 13% CFG Minority Shareholding

For Immediate Release City Football Group Signals China Growth as CMC Holdings Led Consortium Acquires 13% CFG Minority Shareholding • Strategic minority shareholding creates unprecedented platform to deliver CFG growth opportunities in China and internationally • Deal values City Football Group at US$3 Billion (Beijing/Manchester/Abu Dhabi, 1 December 2015) City Football Group (CFG), the owner of football related clubs and businesses including Manchester City FC, New York City FC, Melbourne City FC, and a minority shareholder in Yokohama F. Marinos, today announced a partnership with a consortium of high profile Chinese institutional investors led by China’s leading media, entertainment, sports and Internet dedicated investment and operating company CMC (China Media Capital) Holdings. The deal will create an unprecedented platform for the growth of CFG clubs and companies in China and internationally, borne out of CFG’s ability to provide a wealth of industry expertise and resources to the rapidly developing Chinese football industry. The agreement will see the consortium of CMC Holdings and CITIC Capital invest US$400 million to take a shareholding in City Football Group of just over 13%. The deal values the group at US$3 billion. The agreement is subject to regulatory approval in some territories. The announcement follows more than six months of discussions among the parties to find the optimum model and associated strategies for the partnership. The capital from the share acquisition will be used by City Football Group to fund its China growth, further CFG international business expansion opportunities and further develop CFG infrastructure assets. The CFG/CMC partnership is predicated on the opportunity to create new value for CFG in China and beyond by working with CMC, CITIC Capital and the Chinese football industry. -

Bravo: Keeping Focused

CITY v WATFORD | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 14.12.2016 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 14.12.2016 | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY WATFORD BRAVO: KEEPING FOCUSED Explore the extraordinary in Abu Dhabi Your unforgettable holiday starts here Discover the wonders of Abu Dhabi, with its turquoise coastline, breathtaking desert and constant sunshine. Admire modern Arabian architecture as you explore world-class hotels, cosmopolitan shopping malls, and adrenaline-pumping theme parks. There is something for everyone in the UAE’s extraordinary capital. To book call 0345 600 8118 or visit etihadholidays.co.uk CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 6 Pep Guardiola 8 Claudio Bravo 16 Showcase 20 Buzzword 22 Sequences 28 Access All Areas 34 Short Stay: Ricky Holden 36 Marc Riley 32 My Turf: Nicolas Otamendi 42 Kevin Cummins: Tony Book 46 A League Of Their Own 48 City in the Community 52 Fans: Your Shout 54 Fans: Supporters Club 56 Fans: Social Wrap 58 Fans: Junior Cityzens 62 Teams: EDS 64 Teams: Under-18s 68 Teams: Watford 74 Stats: Match Details 76 Stats: Roll Call 77 Stats: Table 78 Stats: Fixture List 82 Teams: Squads and Officials CLAUDIO BRAVO 8 INTERVIEW Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcofficial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Officer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE,