Democracy, Judging and Bertha Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

644 CANADA YEAR BOOK Governments. the Primary Basis For

644 CANADA YEAR BOOK governments. The primary basis for the division is important issue of law that ought to be decided by the found in Section 2 ofthe criminal code. The attorney court. Leave to appeal may also be given by a general of a province is given responsibility for provincial appellate court when one of itsjudgments proceedings under the criminal code. The attorney is sought to be questioned in the Supreme Court of general of Canada is given responsibility for criminal Canada. proceedings in Northwest Territories and Yukon, and The court will review cases coming from the 10 for proceedings under federal statutes other than the provincial courts of appeal and from the appeal criminal code. Provincial statute and municipal division ofthe Federal Court of Canada. The court is bylaw prosecutions are the responsibility ofthe also required to consider and advise on questions provincial attorney general. referred to it by the Governor-in-Council. It may also Prosecutions may be carried out by the police or advise the Senate or the House of Commons on by lawyers, depending on the practice ofthe attorney private bills referred to the court under any rules or general responsible. If he prosecutes using lawyers, orders of the Senate or of the House of Commons. the attorney general may rely on full-time staff The Supreme Court sits only in Ottawa and its lawyers, or he may engage the services of a private sessions are open to the public. A quorum consists of practitioner for individual cases. five members, but the full court of nine sits in most A breakdown of criminal prosecution expenditures cases; however, in a few cases, five are assigned to sit, by level of government in 1981-82 shows that 75% and sometimes seven, when a member is ill or was paid by the provinces (excluding Alberta), 24% disqualifies himself Since most of the cases have by the federal government and 1% by the territories. -

A Rare View Into 1980S Top Court

A rare view into 1980s top court New book reveals frustrations, divisions among the judges on the Supreme Court By KIRK MAKIN JUSTICE REPORTER Thursday, December 4, 2003- Page A11 An unprecedented trove of memos by Supreme Court of Canada judges in the late 1980s reveals a highly pressured environment in which the court's first female judge threatened to quit while another judge was forced out after plunging into a state of depression. The internal memos -- quoted in a new book about former chief justice Brian Dickson -- provide a rare view into the inner workings of the country's top court, which showed itself to be badly divided at the time. The book portrays a weary bench, buried under a growing pile of complex cases and desperately worried about its eroding credibility. One faction complained bitterly about their colleagues' dithering and failure to come to grips with their responsibilities, according to memos seen for the first time by the authors of Brian Dickson: A Judge's Journey. The authors -- Mr. Justice Robert Sharpe of the Ontario Court of Appeal and University of Toronto law professor Kent Roach -- also interviewed many former judges and ex-clerks privy to the inner workings of the court at arguably the lowest point in its history. "The court was struggling with very difficult issues under very difficult circumstances at the time," Prof. Roach said yesterday. "It was a court that had an incredible amount on its plate and, in retrospect, we were well served by that court." The chief agitators were Mr. Justice Antonio Lamer and Madam Justice Bertha Wilson. -

An Unlikely Maverick

CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND 795 “THE MAVERICK CONSTITUTION” — A REVIEW OF CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND, WILLIAM KAPLAN (TORONTO: UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS FOR THE OSGOODE SOCIETY FOR CANADIAN LEGAL HISTORY, 2009) When a man has risen to great intellectual or moral eminence; the process by which his mind was formed is one of the most instructive circumstances which can be unveiled to mankind. It displays to their view the means of acquiring excellence, and suggests the most persuasive motive to employ them. When, however, we are merely told that a man went to such a school on such a day, and such a college on another, our curiosity may be somewhat gratified, but we have received no lesson. We know not the discipline to which his own will, and the recommendation of his teachers subjected him. James Mill1 While there is today a body of Canadian constitutional jurisprudence that attracts attention throughout the common law world, one may not have foreseen its development in 1949 — the year in which appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (Privy Council) were abolished and the Supreme Court of Canada became a court of last resort. With the exception of some early decisions regarding the division of powers under the British North America Act, 1867,2 one would be hard-pressed to characterize the Supreme Court’s record in the mid-twentieth century as either groundbreaking or original.3 Once the Privy Council asserted its interpretive dominance over the B.N.A. -

Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arran

■ Diversifying the bar: lawyers make history Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present Click here to download Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 1: 1797 to 1941 For each lawyer, this document offers some or all of the following information: name gender year and place of birth, and year of death where applicable year called to the bar in Ontario (and/or, until 1889, the year admitted to the courts as a solicitor; from 1889, all lawyers admitted to practice were admitted as both barristers and solicitors, and all were called to the bar) whether appointed K.C. or Q.C. name of diverse community or heritage biographical notes name of nominating person or organization if relevant sources used in preparing the biography (note: living lawyers provided or edited and approved their own biographies including the names of their community or heritage) suggestions for further reading, and photo where available. The biographies are ordered chronologically, by year called to the bar, then alphabetically by last name. To reach a particular period, click on the following links: 1941-1950, 1951-1960, 1961-1970, 1971-1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-. To download the biographies of lawyers called to the bar before 1941, please click Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present For more information on the project, including the set of biographies arranged by diverse community rather than by year of call, please click here for the Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History home page. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

2000 a Tone of Timidity Final Appeal

922 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW VOL. 38(3) 2000 A TONE OF TIMIDITY FINAL APPEAL: DECISION-MAKING IN CANADIAN COURTS OF APPEAL by Ian Greene, Carl Baar, Peter McCormick, George Szablowski, and Martin Thomas (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1998) I. INTRODUCTION The five co-author of Final Appeal 1 have written the first study of Canadian appellate court decision-making in the ten provinces, the Federal Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court of Canada. Threaded throughout the book are interrelated themes concerning the exercise of judicial discretion as it affects public policy, the legitimacy of an unelected judiciary in Canadian democracy, and the suitability of the judicial appointment process. This work is destined to join the ranks of those other legal and political science studies which have contributed to a more systematic examination of the third branch of Canadian government. Regrettably, the width of the subject matter considered in Final Appeal far exceeds the depth of the analysis. The sequence of the chapters should have been organized more tightly, the analyses of the responses to the judicial questionnaire and the empirical data should have been expressed more sharply, and the prescriptions for change should have been stated more boldly. The catalyst for this project was a gentle chastisement of academics by Justice Bertha Wilson in 1986 for having done very little research on appellate court decision making.2 Therefore, the project was conceived in deference to a judicial suggestion, and the analyses and prescriptions are marked by a pronounced tone of timidity throughout the book. If the authors believed that they had perceived an ideal of the law's future, they should not have "hesitated to point it out and to press toward it with all [their] heart[s]." 3 Otherwise, the reform which they desire will not occur. -

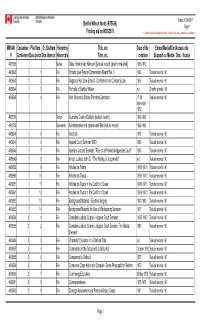

Bertha Wilson Fonds (R15636) Finding Aid No MSS2578 MIKAN

Date: 21/06/2017 Bertha Wilson fonds (R15636) Page 1 Finding aid no MSS2578 Y:\App\Impromptu\Mikan\Reports\Description_reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers_simplelist.im MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent/Media/Dim/Access cde # Contenant Dos./pièce Dos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 4938705 Series Osler, Hoskin and Harcourt [textual record, graphic material] 1965-1972 4939542 1 1 File Ontario Law Reform Commission Report No. 1 1965 Textual records / 90 4939543 1 2 File Osgoode Hall Law School - Conference on Company Law 1965 Textual records / 90 4939544 1 3 File Portraits of Bertha Wilson n.d Graphic (photo) / 90 4939545 1 4 File York Un ive rsity Estate Planning Seminars 17-18 Textual records / 90 November 1972 4938706 Series Supreme Court of Ontario [textual record] 1962-1982 4938708 Sub-series Administrative and operational files [textual record] 1962-1982 4939546 1 5 File Abortion 1976 Textual records / 90 4939547 1 6 File Appeal Court Seminar 1980 1980 Textual records / 90 4939548 1 7 File Apellate Judges' Seminar, "Role of a Provincial Appellate Court" 1980 Textual records / 90 4939549 1 8 File Arnup, Justice John D., "The Writing of Judgments" n.d Textual records / 90 4939550 1 9 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939550 1 10 File Articles on Trusts [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 11 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict of Laws [1975-1981] Textual records / 90 4939551 1 12 File Articles on Trusts in the Conflict -

Justice Bertha Wilson Law and Society Series W

Justice Bertha Wilson Law and Society Series W. Wesley Pue, General Editor The Law and Society Series explores law as a socially embedded phenomenon. It is premised on the understanding that the conventional division of law from society creates false dichotomies in thinking, scholarship, educational practice, and social life. Books in the series treat law and society as mutually constitutive and seek to bridge scholarship emerging from interdisciplinary engagement of law with disciplines such as politics, social theory, history, political economy, and gender studies. A list of the titles in this series appears at the end of this book. Edited by Kim Brooks Justice Bertha Wilson One Woman’s Difference © UBC Press 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on ancient-forest-free paper (100% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Justice Bertha Wilson : one woman’s difference / edited by Kim Brooks. (Law and society, 1496-4953) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7748-1732-5 (bound) 1. Wilson, Bertha, 1923-2007. 2. Canada. Supreme Court – Biography. 3. Women judges – Canada – Biography. 4. Judges – Canada – Biography. I. Brooks, Kim II. -

Introduction

Introduction wo women sat quietly together around a side table in a sparsely furnished ofce in the Supreme Court of TCanada. Te sombre wood-panelled judge’s chambers belonged to Bertha Wilson. Te room contained nothing fancy: a desk, and several chairs, no carpet, the plainest of décor.1 Te women sitting there were sharing a singular conversation. Wilson had been appointed to the Supreme Court in 1982, the frst woman out of ffy-eight judges in the Ottawa court’s 107-year history. Claire L’Heureux-Dubé was appointed the second woman in 1987. Te two were refecting upon what it meant to set toe in the sacrosanct circle restricted for genera- tions to men.2 Te conversation was not without levity. A friend of L’Heureux-Dubé’s had sent her a framed cartoon, a caricature of her with tousled hair and a broad grin sporting the French caption: “Yahoo! J’arrive Bertha!”3 But the dominant tone in Wilson’s ofce that afernoon was not celebratory. Recalling her own reception, Wilson explained to her new colleague that she had felt forced to “prove herself” to a group of men who were skeptical about whether she had won the position on her merits.4 Wilson cautioned L’Heureux-Dubé that she too would have to prove herself all over again.5 “We have to prove ourselves every INTRODUCTION | 7 “Yahoo! J’arrive Bertha!” Photo taken in L’Heureux-Dubé’s Supreme Court Chambers, lef to right, Secretary Lisette Gammon, Claire L’Heureux-Dubé, Law Clerk Teresa Scassa, in front of caricature portrait. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian 2008 CanLIIDocs 196 Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

Justice Bertha Wilson: a Classically Liberal Judge Kent Roach

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 41 (2008) Article 10 Justice Bertha Wilson: A Classically Liberal Judge Kent Roach Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Roach, Kent. "Justice Bertha Wilson: A Classically Liberal Judge." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 41. (2008). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol41/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Justice Bertha Wilson: A Classically Liberal Judge Kent Roach* I. INTRODUCTION Bertha Wilson will be remembered as the first woman to sit on the Supreme Court. Historians will look to her decisions in R. v. Morgentaler1 and R. v. Lavallee2 as signs that, to paraphrase Justice Wilson’s famous speech, she really did make a difference as the first woman judge to sit on the Supreme Court.3 It is undeniable that Justice Wilson made a difference. It is very likely that Justice Wilson’s gender and her experiences with discrimination4 shaped her personality and her approach to judging. Nevertheless, in this essay, I will argue that Justice Wilson’s approach to judging was most influenced by her classical liberalism that defended the rights of the individual against the power of the state. -

Bertha Wilson Honour Society Schulich School of Law Dalhousie University

BERTHA WILSON HONOUR SOCIETY SCHULICH SCHOOL OF LAW DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY The late Honourable Bertha Wilson was a native of Kirkcaldy, Scotland. Soon after earning a masters degree from the University of Aberdeen she emigrated along with her husband, John Wilson, a Presbyterian minister, to Canada in 1949. John took up a ministry in Renfrew, Ontario. During the Korean War he served a six-year secondment as a naval chaplain. Wilson joined him in Halifax and enrolled at Dalhousie Law School where she graduated near the top of her class. She was called to the Nova Scotia bar in 1957. She moved to Toronto in 1959, was called to the Ontario bar and joined the law firm of Osler Hoskin Harcourt and practiced there for 17 years. In 1975, she was the first woman appointed to the Ontario Court of Appeal. In 1982, then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau appointed her to the Supreme Court of Canada; she was the first female justice to serve. At the time of her death Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, on behalf of the Supreme Court of Canada, stated: “Bertha Wilson was known for her generosity of spirit and originality of thought. She was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada the same year the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was enacted. As a member of this court, she was a pioneer in Charter jurisprudence and made an outstanding contribution to the administration of justice. She will be sorely missed by all who were privileged to know her.” The Bertha Wilson Honour Society at the Schulich School of Law recognizes extraordinary alumni and showcases their geographic reach.