The Tread of a White Man's Foot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lonely Island

The Lonely Island By R. M. Ballantyne The Lonely Island Chapter One. The Refuge of the Mutineers. The Mutiny. On a profoundly calm and most beautiful evening towards the end of the last century, a ship lay becalmed on the fair bosom of the Pacific Ocean. Although there was nothing piratical in the aspect of the shipif we except her gunsa few of the men who formed her crew might have been easily mistaken for roving buccaneers. There was a certain swagger in the gait of some, and a sulky defiance on the brow of others, which told powerfully of discontent from some cause or other, and suggested the idea that the peaceful aspect of the sleeping sea was by no means reflected in the breasts of the men. They were all British seamen, but displayed at that time none of the wellknown hearty offhand rollicking characteristics of the Jacktar. It is natural for man to rejoice in sunshine. His sympathy with cats in this respect is profound and universal. Not less deep and wide is his discord with the moles and bats. Nevertheless, there was scarcely a man on board of that ship on the evening in question who vouchsafed even a passing glance at a sunset which was marked by unwonted splendour. The vessel slowly rose and sank on a scarce perceptible oceanswell in the centre of a great circular field of liquid glass, on whose undulations the sun gleamed in dazzling flashes, and in whose depths were reflected the fantastic forms, snowy lights, and pearly shadows of cloudland. -

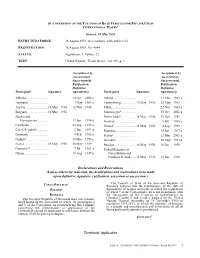

Unless Otherwise Indicated, the Declarations and Reservations Were Made Upon Definitive Signature, Ratification, Accession Or Succession.)

10. CONVENTION ON THE TAXATION OF ROAD VEHICLES FOR PRIVATE USE IN INTERNATIONAL TRAFFIC Geneva, 18 May 1956 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 18 August 1959, in accordance with article 6(2). REGISTRATION: 18 August 1959, No. 4844. STATUS: Signatories: 8. Parties: 23. TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 339, p. 3. Acceptance(A), Acceptance(A), Accession(a), Accession(a), Succession(d), Succession(d), Ratification, Ratification, Definitive Definitive Participant Signature signature(s) Participant Signature signature(s) Albania.........................................................14 Oct 2008 a Ireland..........................................................31 May 1962 a Australia....................................................... 3 May 1961 a Luxembourg.................................................18 May 1956 28 May 1965 Austria .........................................................18 May 1956 12 Nov 1958 Malta............................................................22 Nov 1966 a Belgium .......................................................18 May 1956 Montenegro5 ................................................23 Oct 2006 d Bosnia and Netherlands6.................................................18 May 1956 20 Apr 1959 Herzegovina1..........................................12 Jan 1994 d Norway ........................................................ 9 Jul 1965 a Cambodia.....................................................22 Sep 1959 a Poland7.........................................................18 May 1956 4 Sep 1969 Czech -

Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Arts Papers and Journal Articles School of Humanities and Creative Arts 6-7-2016 Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director Stephen Vagg FremantleMedia Australia, [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/arts_papers Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Vagg, S., & Reynaud, D. (2016). Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten pioneer Australian film director. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 10(2),184-198. doi:10.1080/17503175.2016.1170950 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities and Creative Arts at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Papers and Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director Stephen Vagg Author and screenwriter, Melbourne Victoria, Australia Email: [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Faculty of Arts, Nursing & Theology, Avondale College of Higher Education, Cooranbong, NSW, Australia Email: [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Postal address: PO Box 19, Cooranbong NSW 2265 Phone: (02) 4980 2196 Bios: Stephen Vagg has a MA Honours in Screen Studies from the Australian Film, Television and Radio School and has written a full-length biography on Rod Taylor. He is also an AWGIE winning and AFI nominated screenwriter who is currently story producer on Neighbours. Daniel Reynaud is Associate Professor of History and Faculty Assistant Dean, Learning and Teaching. He has published widely on Australian war cinema and was instrumental in the partial reconstruction of Rolfe’s film The Hero of the Dardanelles, and the rediscovery of parts of How We Beat the Emden. -

The Story of Aliko and Ambai

The Story of Aliko and Ambai: Cinema and Social Change in Papua New Guinea A project submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Mark Asbury Eby Bachelor of Arts, PLNU, Master of Arts, UCLA School of Media and Communication College of Design and Social Context RMIT University June 2017 Declaration I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the project is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Mark Asbury Eby 30 June 2017 ii The Story of Aliko and Ambai Cinema and Social Change In Papua New Guinea iii Acknowledgements I thank my senior supervisor, Professor Heather Horst, for supporting me through the writing process of this project. Heather has never wavered in her steady, measured, conscientious and thoughtful responses to the constant stream of writing I have created in regards to my film production practice over the last few years. My overly- narrative writing style may not have been the best fit for academia but Heather’s patience, good humour, monthly word quotas, and continued requests for more analysis and less description has guided me to the finish line. I also appreciate being mentored through the academic publishing process, resulting in a publication at the end of last year. -

Adt-NU1999.0010Chapter8.Pdf (PDF, 33.93KB)

1 chapter 8 conclusion She 'ad three clothes-pegs in 'er mouth, an' washin' on 'er arm — 1 This intertitle, from the 1920 Raymond Longford film, Ginger Mick, the sequel to The Sentimental Bloke, perfectly describes the mother of early films. One of the scores of missing Australian feature films, Ginger Mick carried on the tale of Doreen's life with her husband, the Bloke, and their baby son, who is born at the close of the earlier film.2 The words of the intertitle in Ginger Mick are accompanied on screen by a line drawing in order to make the meaning quite clear. In the foreground is a large, round, wooden tub. A washboard is perched on the shelf behind it, close to a bottle of Lysol. The figure of the hard-working mother is in the background near a clothesline, where enormous sheets blow in the wind, dwarfing her. Bent almost double over her washing basket, she labours beside a long prop which rests on the ground, ready for her to lift the heavy line into the wind. The film has been lost and we really have no idea who the woman was supposed to be, although the drawing invites speculation. Could she possibly be the lovely, desirable Doreen, the apple of the Bloke's eye, now a housewife and drudge? Perhaps, on the other hand, it is just a generic sketch of motherhood. Either way, the words and the drawing illustrate the stereotypical mother of the early days of cinema, who was constantly occupied with the family's washing.3 The activity is a visual metaphor for her diligence, her uncomplaining care of the family and her regard for cleanliness. -

Keith Connolly

KEITH CONNOLLY (1897-1961) Keith Connolly performed with his parents' variety troupe from age seven and while in his teens was a member of the Young Australia League. In 1916 he enlisted with the A.I.F. and went on to serve with the Mining Corps. After returning home in 1919 he and his sister Gladys Shaw toured with such troupes as the Royal Strollers (1919) and Nat Phillips' Stiffy and Mo Company (1921-25) before forming Keith's Syncopating Jesters (1925-27). Connolly's career, which continued well into the 1950s, included engagements with George Wallace (1930), Nat Phillip's Whirligigs, Fullers All-American Revue Co (including New Zealand, 1939) and in companies featuring Roy Rene, Stud Foley, Nellie Kolle and his wife, Elsie Hosking. 1897-1918 Keith Connolly’s earliest engagements earned him enthusiastic reviews: ….absolutely the youngest character comedian on the vaudeville stage, 'Master Keith' (who is only 8 years of age)…gives remarkable imitations of the leading English and American character comedians such as Little Tich, Dan Leno etc.…1 The Sydney Daily Telegraph in speaking of this item says: - 'His songs and imitations, as well as his comic make-up, kept the audience in roars of laughter, and he was recalled again and again. We have listened to many adult comedians and have enjoyed their performances, but the extreme youth of this clever performer, coupled with his marvellous power of imitation, at once captivated all hearts.'2 Keith Warrington Connolly's father was Gerald Shaw (aka Harry Thomson) an enthusiastic basso and theatrical manager with an early interest in moving pictures. -

(Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) És Una Pel·Lícula Norda

La legendària rebel·lió a bord de la Bounty La tragèdia de la Bounty (Mutiny on the Bounty , 1935) és una pel·lícula nordamericana, dirigida per Frank Lloyd, i interpretada per Clarck Gable i Charles Laughton, que relata la història de l'amotinament dels mariners de la Bounty . El 28 d'abril de 1789, 31 dels 46 homes del veler de l'armada britànica Bounty s'amotinaren. L'oficial Fletcher Christian encapçalà l'amotinament contra el comandant de la nau, el tinent William Bligh, un marí amb experiència, que havia acompanyat Cook en el seu tercer viatge al Pacífic. La nau havia marxat a la Polinèsia per tal d'arreplegar especímens de l'arbre del pa, per tal de dur-los al Carib, perquè els seus fruits, rics en glúcids, serviren d'aliment als esclaus. El 26 d'octubre de 1788 ja havien carregat 1015 exemplars de l'arbre. En començar el viatge de tornada es va produir l'amotinament i els mariners llançaren els arbres al mar. Bligh i 18 homes foren abandonats en un bot. En 1790, després de 6.000 km de navegació heròica, arribaren a Gran Bretanya. L'armada britànica envià un vaixell per reprimir el motí, el Pandora , comandat per Erward Edwards. Va matar 4 amotinats. Per haver perdut la nau, Bligh va patir un consell de guerra. En 1804 fou governador de Nova Gal·les del Sud (Austràlia) i la seua repressió del comerç de rom provocà una revolta. L'única colònia britànica que queda en el Pacífic són les illes Pitcairn. Els seus 50 habitants (dades 2010) viuen en la major de les illes, de 47 km 2. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea By Ida Lee Captain Bligh's Second Voyage To The South Sea CHAPTER I. THE SHIPS LEAVE ENGLAND. On Wednesday, August 3rd, 1791, Captain Bligh left England for the second time in search of the breadfruit. The "Providence" and the "Assistant" sailed from Spithead in fine weather, the wind being fair and the sea calm. As they passed down the Channel the Portland Lights were visible on the 4th, and on the following day the land about the Start. Here an English frigate standing after them proved to be H.M.S. "Winchelsea" bound for Plymouth, and those on board the "Providence" and "Assistant" sent off their last shore letters by the King's ship. A strange sail was sighted on the 9th which soon afterwards hoisted Dutch colours, and on the loth a Swedish brig passed them on her way from Alicante to Gothenburg. Black clouds hung above the horizon throughout the next day threatening a storm which burst over the ships on the 12th, with thunder and very vivid lightning. When it had abated a spell of fine weather set in and good progress was made by both vessels. Another ship was seen on the 15th, and after the "Providence" had fired a gun to bring her to, was found to be a Portuguese schooner making for Cork. On this day "to encourage the people to be alert in executing their duty and to keep them in good health," Captain Bligh ordered them "to keep three watches, but the master himself to keep none so as to be ready for all calls". -

Ethnographic Film-Making in Australia: the First Seventy Years

ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM-MAKING IN AUSTRALIA THE FIRST SEVENTY YEARS (1898-1968) Ian Dunlop Ethnographic film-making is almost as old as cinema itself.1 In 187 7 Edison, in America, perfected his phonograph, the world’s first machine for recording sound — on fragile wax cylinders. He then started experimenting with ways of producing moving pictures. Others in England and France were also experimenting at the same time. Amongst these were the Lumiere brothers of Paris. In 1895 they perfected a projection machine and gave the world’s first public screening. The cinema was born. The same year Felix-Louis Renault filmed a Wolof woman from west Africa making pots at the Exposition Ethnographique de l’Afrique Occidentale in Paris.2 Three years later ethnographic film was being shot in the Torres Strait Islands just north of mainland Australia. This was in 1898 when Alfred Cort Haddon, an English zoologist and anthro pologist, mounted his Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Strait. His recording equipment included a wax cylinder sound recorder and a Lumiere camera. The technical genius of the expedition, and the man who apparently used the camera, was Anthony Wilkin.3 It is not known how much film he shot; unfortunately only about four minutes of it still exists. It is the first known ethnographic film to be shot in the field anywhere in the world. It is of course black and white, shot on one of the world’s first cameras, with a handle you had to turn to make the film go rather shakily around. The fragment we have shows several rather posed shots of men dancing and another of men attempting to make fire by friction. -

I Certify That the Thesis Entitled Twisted Things

I certify that the thesis entitled Twisted Things: Playing with Time submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is the result of my own work and that where reference is made to the work of others, due acknowledgment is given. I also certify that any material in the thesis which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by any university or institution is identified in the text. ʹI certify that I am the student named below and that the information provided in the form is correctʹ Full Name: Virginia Stewart Murray Signed ..................................................................................…….… Date .................................................................................…….…… Twisted Things: Playing with Time by Virginia Stewart Murray (BA Dip Ed) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University January 2012 Table of Contents Volume One Creative Component Introduction to Thesis 1 Preface: Neither Fish nor Fowl 3 TWISTED THINGS 7 Volume Two Exegesis Playing with time: an exegesis in three chapters Introduction 127 Chapter One: On the Beach: A Contextual History Part 1 141 Part II 158 Chapter 2: Glamour and Celebrity: 1950s Australian Style 172 Chapter 3: The Role of the Unconscious: Playing with Time in Film 236 Camera Consciousness and Reterritorialisation in 12 Monkeys 249 Sheets of the Past in Jacob’s Ladder 257 Incompossible Worlds in Donnie Darko 264 Suddenly Thirty and the Peaks of the Present 269 Conclusion 280 Works Cited 287 Filmography 299 Works Consulted -

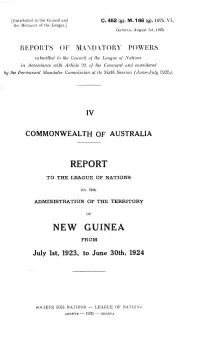

Report New Guinea

[Distributed to the Council and C. 452 (g), M.166 (g). 1925. VI. the Members of the League.] G e n e v a , August 1st, 1925. REPORTS OF MANDATORY POWERS submilled to the Council of the League of Nations in Accordance with Article 22 of the Covenant and considered by the Permanent Mandates Commission at its Sixth Session (June-July 1925). IV COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA REPORT TO THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE TERRITORY OF NEW GUINEA FROM July 1st, 1923, to June 30th, 1924 SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS — LEAGUE OF NATIONS G E N È V E --- 1925 GENEVA NOTES BY THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS This edition of the reports submitted to the Council of the League of Nations by the mandatory Powers under Article 22 of the Covenant is published in execu tion of the following resolution adopted by the Assembly on September 22nd, 1924, at its Fifth Session : “ The Fifth Assembly . requests that the reports of the mandatory Powers should be distributed to the States Members of the League of Nations and placed at the disposal of the public who may desire to purchase them. ” The reports have generally been reproduced as received by the Secretariat. In certain cases, however, it has been decided to omit in this new edition certain legislative and other texts appearing as annexes, and maps and photographs contained in the original edition published by the mandatory Power. Such omissions are indicated by notes by the Secretariat. The annual report to the League of Nations on the administration of the Territory of New Guinea from July 1st, 1923, to June 30th, 1924, was received by the Secretariat on June 2nd 1925, and examined by the Permanent Mandates Commission on July 1st, 1925, in the presence of the accredited representative of the Australian Government, the Hon.