The Fetishization of Viewscapes in Western Amenity Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tildeling Av Skjønnsmidler 2021 Trøndelag (Forhåndsfordelt Og 1

Vår dato: Vår ref: 19.11.2020 2020/7330 Deres dato: Deres ref: «REFDATO» «REF» «MOTTAKERNAVN» Saksbehandler, innvalgstelefon «ADRESSE» Sigrid Hynne, 74 16 80 79 «POSTNR» «POSTSTED» «KONTAKT» Tildeling av skjønnsmidler 2021 Trøndelag (forhåndsfordelt og 1. tildeling av tilbakeholdte midler) Trøndelag ble tildelt 98 mill. kr av den fylkesvise skjønnsrammen for 2021. På statsbudsjettkonferansen for Trøndelag som ble avholdt 8. oktober presenterte Fylkesmannen fordelingen av skjønnsmidler for 2020 og 2021. Dette brevet beskriver hva som så langt er fordelt til kommunene for 2021. Vedlegg 1 viser fordeling per kommune, mens vedlegg 2 inneholder oversikt over hvilke prosjekter som er tildelt skjønnsmidler for 2021 (fornying og innovasjon). Deler av skjønnsrammen vil holdes tilbake til fordeling gjennom 2021. I oktober neste år vil vi derfor komme tilbake med en samlet oppsummering av skjønnstildelingen for 2021. Skjønnsmidler 2020 For 2020-midlene viser vi til brev til KMD datert 15.10.2020, og som ble sendt i kopi til kommunene i fylket. På denne nettsiden ligger det en excel-fil som viser oversikt over fordeling av skjønn for 2020, der det er mulig å filtrere per kommune: https://www.fylkesmannen.no/nb/Trondelag/Kommunal- styring/Kommuneokonomi/Skjonnsmidler/ I tillegg vil vi i starten av desember sende et brev til kommunene om fordeling av ekstraordinære skjønnsmidler 2020 begrunnet i koronasituasjonen. Disse skjønnsmidlene blir utbetalt i desember. Om skjønnstildeling og retningslinjer Med bakgrunn i Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementets retningslinjer, og gjennom konsultasjon med kommunene, har Fylkesmannen i Trøndelag utviklet en tildelingsmodell med tilhørende retningslinjer (sist oppdatert mai 2020). Skjønnstildelingen bygger på hovedkomponentene kompensasjonsskjønn og prosjektskjønn, der prosjektskjønn dekker innovasjon og fornyingsprosjekter i enkeltkommuner og i samarbeid med flere, i tillegg til fellesløft (fellestiltak) for hele fylket. -

Petrography, Geochemistry and Genesis of the Skiftesmyr Cu-Zn VMS- Deposit, Grong, Norway

FACULTY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY Petrography, geochemistry and genesis of the Skiftesmyr Cu-Zn VMS- deposit, Grong, Norway Kristoffer Jøtne Walsh GEO-3900 Master’s Thesis in Geology November 2013 GEO-3900 Master’s Thesis in Geology PETROGRAPHY, GEOCHEMISTRY AND GENESIS OF THE SKIFTESMYR CU-ZN VMS-DEPOSIT, GRONG, NORWAY Kristoffer Jøtne Walsh Department of Geology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, November, 2013 2 3 Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisors, Professor Kåre V. Kullerud and Perry O. Kaspersen, former CEO and Country Manager of MetPro AS, for all their help and comments, and MetPro AS for making this thesis possible. I would also like to thank Professor Erling Krogh Ravna for assistance with the XRF analyses, and express my gratitude to former MetPro AS geologist Stefan Winterhoff for assistance with field work, and Per Samskog, MetPro AS exploration geologist, for MapInfo tutoring. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my family, friends and fellow students for their support and encouragement. Kristoffer Jøtne Walsh Tromsø, Nov. 2013 4 5 Abstract The Skiftesmyr Cu-Zn VMS-deposit is located in the Grong municipality of Northern Trøndelag, Norway. The mineralization has been known since at least 1903, when mention of small workings in the area were first published, and has later been the subject of several exploration projects by different companies, of which MetPro AS is the latest. The Skiftesmyr deposit is a part of the Gjersvik Nappe, which is a part of the Köli Nappe Complex, which in turn is a part of the Upper Allochthon of the Scandinavian Caledonides, and is likely of Mid- Ordovician age. -

232 Norway Norge for Updates, Visit

232 Norway Norge For Updates, visit www.routex.com 8 9Murmansk 7 6 5 3 4 Helsinki Tallinn Bergen Oslo 1 2 Stockholm Rīga Göteborg N_Landkarte.indd 232 05.11.12 12:50 Norge Norway 233 Øvre Høyanger Sogndal Hyllestad Årdal Balestrand Leikanger Hardbakke Vikøyri 42 Lærdalsøyri Byrknes Aurlandsvangen Lindås Voss Meland 61 94 Lonevåg Askøy Bergen Straume Norheimsund 49 09 Sund 59 Osøyro Odda Rosendal Bømlo Tinn 20 63 Ølen Sletta Haugesund Tysvær Kopervik N 79 Strand 74 Stavanger Sola 01 Kleppe Gjesdal Bryne 75 Vigrestad Eigersund Arendal 48 Grimstad Flekkefjord Vennesla 83 Lyngdal Kristiansand Farsund Søgne Mandal N_Landkarte.indd 233 05.11.12 12:50 234 Norway Norge Trysil Follebu 47 73 Fagernes 22 13 25 Dokka Løten Hamar 05 26 Kapp 27 Stange Raufoss 17 50 80 Gran Eidsvoll 33 Lunner Jevnaker Nannestad Hønefoss Jessheim 37 24 21 Årnes 72 66 Hole 65 Sørumsand Skotterud Lillestrøm Modum Fetsund Tinn Oslo Bjørkelangen 67 16 Nedre Lier Hokksund Eiker Enebakk Røyken Ski Drammen 46 Arvika Kongsberg Drøbak 96 31 64 Sande Svelvik Askim Notodden Hurum 56 Mysen 32 Våle Moss Rakkestad Horten Rygge 76 12 Karlshus Nome 78 Sarpsborg 82 Tønsberg 62 Fredrikstad Stokke Nøtterøy Sandefjord 23 Halden Porsgrunn 68 86 Larvik 91 Kragerø Risør Arendal Skagerrak Vänersborg Grimstad Uddevalla Trollhättan Lysekil Henån Stenungsund Skärhamn Kattegat N_Landkarte.indd 234 05.11.12 12:50 Norge Norway 235 Sulsfjorden Frøya Fillan Smøla 38 Aure Liabø 39 Kårvåg Surnadalsøra Eide Batnfjordsøra Tingvoll Elnesvågen Steinshamn Aukra 54 Eidsvåg Molde Midsund Moldefjorden Sunndalsøra -

Taxi Midt-Norge, Trøndertaxi Og Vy Buss AS Skal Kjøre Fleksibel Transport I Regionene I Trøndelag Fra August 2021

Trondheim, 08.02.2021 Taxi Midt-Norge, TrønderTaxi og Vy Buss AS skal kjøre fleksibel transport i regionene i Trøndelag fra august 2021 Den 5. februar 2021 vedtok styret i AtB at Taxi Midt-Norge, TrønderTaxi og Vy Buss AS får tildelt kontraktene for fleksibel transport i Trøndelag fra august 2021. Transporttilbudet vil være med å utfylle rutetilbudet med buss. I tillegg er det tilpasset både regionbyer og distrikt, med servicetransport i lokalmiljøet og tilbringertransport for å knytte folk til det rutegående kollektivnettet med buss eller tog. Fleksibel transport betyr at kundene selv forhåndsbestiller en tur fra A til B basert på sitt reisebehov. Det er ikke knyttet opp mot faste rutetider eller faste ruter, men innenfor bestemte soner og åpningstider. Bestillingen skjer via bestillingsløsning i app, men kan også bestilles pr telefon. Fleksibel transport blir en viktig del av det totale kollektivtilbudet fra høsten 2021. Tilbudet er delt i 11 kontrakter. • Taxi Midt-Norge har vunnet 4 kontrakter og skal tilby fleksibel transport i Leka, Nærøysund, Grong, Høylandet, Lierne, Namsskogan, Røyrvik, Snåsa, Frosta, Inderøy og Levanger, deler av Steinkjer og Verdal, Indre Fosen, Osen, Ørland og Åfjord. • TrønderTaxi har vunnet 4 kontakter og skal tilby fleksibel transport i Meråker, Selbu, Tydal, Stjørdal, Frøya, Heim, Hitra, Orkland, Rindal, Melhus, Skaun, Midtre Gauldal, Oppdal og Rennebu. • Vy Buss skal drifte fleksibel transport tilpasset by på Steinkjer og Verdal, som er en ny og brukertilpasset måte å tilby transport til innbyggerne på, og som kommer i tillegg til rutegående tilbud med buss.Vy Buss vant også kontraktene i Holtålen, Namsos og Flatanger i tillegg til to pilotprosjekter for fleksibel transport i Røros og Overhalla, der målet er å utvikle framtidens mobilitetstilbud i distriktene, og service og tilbringertransport i områdene rundt disse pilotområdene. -

294 002 Myrene I Fillan Herred Sør-Trøndelag Fylke

MYRENE, I FILLAN HERRED 85 MYRENE I FILLAN HERRED, SØR-TRØNDELAG FYLKE. Av konsulent Ose. Hovde. Fl 11 an herred består av nordøstre del av øya Hitra og dessuten av flere mindre øyer og holmer nord-Øst for Hitra i sør-Trøndelag fylke. Geografisk sett ligger herredet mellom 63° 32' 42" og 63° 44' 41" nordlige bredde og 1 ° 26' 24" og 1 ° 50' 9'' vestlig lengde, regnet fra Oslo meridian. Fillan grenser til herredene Sandstad i sør og Hitra i vest. I nord og øst begrenses herredet av hav, nemlig henholdsvis Frøysjøen og Frohavet. De nærmeste herreder er: I nord Nord-Frøya og i øst Ørland. Fillfjorden danner skille mellom Hitra og herredets andre Øyer, hvorav Fjellværøy og Ulvøy er de største. Herredets totalareal er 113,38 km- og landarealet utgjør 108,72 km2• Herav ligger omtrent ¾ på Hitra. Fillan har småkupert landskap, men ingen hØye fjell. De største høyder går opp til ca. 180 mo. h. Langs grensen mot Sandstad finnes en del furuskog, men ellers er de mindre øyer, og største delen av her• redet for øvrig, så godt som skogbart. Jordbruks te 11 ingen av 1949 oppgir ca. 1 km2 skog (ve• sentlig barskog) på de bruk som er med i tellingen, mens skogtellingen regner med ca. 6,5 km2 skog i hele herredet. Av udyrket, dyrkbar fast• marksjord oppgir foran nevnte jordbrukstelling 468 dekar, og av myr 1317 dekar. Jordbruksarealet er oppført med vel 3800 dekar, hvorav vel 3000 dekar er dyrket. Dette areal er fordelt på 188 bruk. Gjennom• snittsstørrelsen på brukene blir således ca. -

Virksomhetens Navn

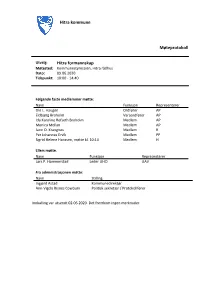

Hitra kommune Møteprotokoll Utvalg: Hitra formannskap Møtested: Kommunestyresalen, Hitra rådhus Dato: 09.06.2020 Tidspunkt: 10:00 - 14:40 Følgende faste medlemmer møtte: Navn Funksjon Representerer Ole L. Haugen Ordfører AP Eldbjørg Broholm Varaordfører AP Ida Karoline Refseth Broholm Medlem AP Monica Mollan Medlem AP Jann O. Krangnes Medlem R Per Johannes Ervik Medlem PP Sigrid Helene Hanssen, møtte kl. 10:10 Medlem H Ellers møtte: Navn Funksjon Representerer Lars P. Hammerstad Leder UHO UAV Fra administrasjonen møtte: Navn Stilling Ingjerd Astad Kommunedirektør Ann-Vigdis Risnes Cowburn Politisk sekretær / Protokollfører Innkalling var utsendt 02.06.2020. Det fremkom ingen merknader. Orienteringer Kommunebarometeret Alle kategorier er ennå ikke avklart. Men i de foreløpige resultater har vi fått beskjed om at Hitra igjen er på 1. plass innen pleie og omsorg. Ellers er det variasjonene i den andre foreløpige resultater, så det skal bli spennende å se hva det ender opp med. Samarbeidsforum Hitra og Frøya Det er berammet møte den 17. juni. Hovedsaken er å utarbeide et innspill til Fylkeskommunen i forbindelse med avbøtende tiltak og gjennomføring av utbedring i Frøyatunnelen. I tillegg er det flere aktuelle samarbeidsområder som må drøftes. Orkdalsregion Det er berammet regionrådsmøte førstkommende fredag, der bommene i «gamle Snillfjord kommune» vil være tema. Saken har vært til behandling i arbeidsutvalget, som består av ordførererne i Skaun (leder), Orkland (nestleder) og Frøya Saken har mange problemstillinger. Hva lå til grunn for bompengepakken? Fordelingen er en takst på 45% ved Våvatnet og 55% ved Valslag. Skal alt kreves inn på Valslag vil bomgebyret for personbil økes med ca. kr 25 pr. -

Planbeskrivelse-1.Pdf

Oppdragsgiver Hitra Kommune Rapporttype Planbeskrivelse 15.09.2015 PLANBESKRIVELSE TIL DETALJREGULERING AV JØSTENØY INDUSTRIOMRÅDE JØSTENØY INDUSTRIOMRÅDE 3 (35) PLANBESKRIVELSE TIL DETALJREGULERING AV JØSTENØY INDUSTRIOMRÅDE Oppdragsnr.: 135 000 7205 Oppdragsnavn: Dokument nr.: 1 Filnavn: Planbeskrivelse - Jøstenøy Revisjon 000 001 002 003 Dato 2015-09-15 2015-12-07 Utarbeidet av Lars Arne Bø, Lars Arne Bø Dorte Solvang Kontrollert av Eirik Lind Godkjent av Eirik Lind Revisjonsoversikt Revisjon Dato Revisjonen gjelder 1 07.12.2015 Endringer etter innspill fra Hitra kommune Rambøll Mellomila 79 4 (35) JØSTENØY INDUSTRIOMRÅDE INNHOLD 1. BAKGRUNN .............................................................................. 6 1.1 Hensikten med planen ................................................................ 6 1.2 Forslagsstiller/eierforhold, plankonsulent ...................................... 6 2. PLANPROSESSEN .................................................................... 6 2.1 Varsel om oppstart og planprosess ............................................... 6 2.2 Krav om konsekvensutredning ..................................................... 7 2.3 Innspill ..................................................................................... 7 3. PLANSTATUS OG RAMMEBETINGELSER ................................... 8 3.1 Statlige planer og føringer ........................................................... 8 3.2 Kommunale (overordnede) planer ................................................ 8 3.3 Gjeldnede reguelringsplaner -

Årbok for Fosen – Årbokartikler Alfabetisk

Artikler i Årbok for Fosen – alfabetisk fra Årsskrift 1947 til Årbok 2020 Ved Eilert Bjørkvik og Johan G Foss Bruk CTRL F for å søke etter ord i lista Forfatter Tittel År og side Aksdal, Bjørn En samling folketoner fra Bjørnør, nedskrevet av Mathias A. Lothe 1985:61 Oløkko fer både her og der. Et dikt fra omgangsskolens tid i Alstad, Karin 1996:77 Snillfjord Alsvik, Elling Om bygdemuseer 1971:7 Interiør og inventar på Austrått. En vandring gjennom slottet på Andersen, Eystein M 2004:7 1700-tallet Andersen, Håkon og Hemmelige katolikker. Et kryptokatolsk miljø omkring kanslerne 2001:123 Bratberg, Terje T. V. Bjelke på 1600-tallet Andersen, Steinar Lekterbygging i Brattåa 2000:105 Andresen, Harald Tragedien utenfor Harbak i 1978 2016:63 Andresen, Harald Staværingen – båten som ble en legende 2017:63 Andresen, Harald Dueskar-grenda i Stjørna før i tia 2018:7 Andresen, Harald Historien om Olbert Fredriksen 2020:077 Andresen, Øystein Staværingen og stormen. Et reiseminne fra 1939 2006:121 Aune, Arnfinn Sauehald og slakting på Hitra 1974:191 Aune, Arnfinn Frå børtre til vassverk på Sandstad 1975:109 Aune, Arnfinn Tresko på Hitra 1976:115 Aune, Arnfinn Hitterværingane og feitsilda 1977:17 Aune, Arnfinn Fosentonane. Natur, folkeliv og ferdsel 1990:7 Aune, Arnfinn Storlygaren. Ein mann av reisande slekt 1991:39 Aune, Arnfinn Hitterværingar i ver og vind 1992:53 Aune, Arnfinn Ordtak frå Hitra 1993:151 Aune, Arnfinn Biletspråk og kallsmål på Trøndelagskysten 1996:113 Aune, Arnfinn Biletspråk frå husdyrhaldet 1997:25 Aune, Arnfinn Ordbilete frå husdyrmiljø 2000:79 Aune, Egil Attåtfor i Fosen 1967:68 Aune, Egil ”Ta i og dra!” – Fra Sørfjord meieri før motoren 1991:43 Aune, Egil Minner fra Holvatnet 2002:65 Aune, Hallgerd og Kjerkgangand kle. -

Trøndelag Fylkeskommune Seksjon Kommunal

Trøndelag fylkeskommune Seksjon Kommunal KYSTPLAN AS Postboks 4 Fillan 7239 HITRA Vår dato: 11.05.2020 Vår referanse: 202011275-7 Vår saksbehandler: Deres dato: Deres referanse: Heidi Beate Flatås Fylkeskommunens uttalelse til nytt varsel om oppstart av reguleringsplan for Haugen - 232/11. Indre fosen kommune Vi viser til deres oversendelse datert 22.april 2020. Vårt faglige råd om at planområdet burde utvides for å legge til rette for gående og syklende langs fv 755 er nå imøtekommet. Vi minner om krav til avstand mellom veg og GSV ved 50 km/t er 1,5 meter. Annen løsning krever fravik. Kulturminner eldre tid Vi viser til våre innspill datert 1.april 2020. Vi vurderer at det er liten risiko for at planen vil komme i konflikt med automatisk fredete kulturminner, og har derfor ingen særskilte merknader til planforslaget. Vi minner imidlertid om den generelle aktsomhets- og meldeplikten etter § 8 i kulturminneloven. Dersom man i løpet av arbeidets gang oppdager noe som kan være et automatisk fredet kulturminne (f.eks. gjenstander, ansamlinger av sot/kull eller stein), skal arbeidet stanses og fylkeskommunen varsles. Vi foreslår at følgende tekst settes inn i reguleringsplanens generelle bestemmelser: Dersom man i løpet av bygge- og anleggsarbeid i marka oppdager gjenstander eller andre spor som viser eldre aktivitet i området, må arbeidet stanses og melding sendes fylkeskommunen og/eller Sametinget omgående, jf. lov 9. juni 1978 nr. 50 om kulturminner (kml) § 8 annet ledd. Kulturminnemyndighetene forutsetter at dette pålegget videreformidles -

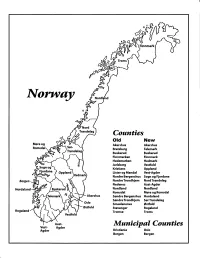

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Tildeling Prosjektskjønn 2021 (Innovasjon Og Fornying)

05.11.20 Tildeling prosjektskjønn 2021 (innovasjon og fornying) Prosjektnr. Tittel Søker Samarbeids- Forutsetninger for tildelingen Tildelt kommuner beløp 50-20-0002 Interkommunal innovativ rekruttering og Melhus kommune Midtre Gauldal, Det forutsettes deltagelse i KS sitt «heltidskulturnettverk» og 1 600 000 kompetanseutvikling av helsepersonell - Skaun at prosjektet er viktig bidragsyter i andre kommuners arbeid videreføringsprosjekt - hovedprosjekt med tilsvarende problemstillinger 50-20-0003 Trygge foreldre, godt foreldreskap og Trondheim kommune 400 000 trygge barn. Liten og ny i barnehagen 50-20-0005 Felles kunnskapsgrunnlag for Oppdal kommune Midtre Gauldal, 340 000 beitebruken i Trollheimen og Ilfjellet. Orkland, Rennebu, Rindal 50-20-0007 Tett på barnehage og skole Namsos kommune Flatanger, Overhalla 1 200 000 50-20-0010 Kommunale kvalitetsindikatorer - Malvik kommune Hitra, Levanger, Det forutsettes deltagelse i KS sitt «heltidskulturnettverk» og 900 000 utvikling av heltidskultur og tiltak med Trondheim, at prosjektet er viktig bidragsyter i andre kommuners arbeid tanke på økt tjenestekvalitet innen Trondheim med tilsvarende problemstillinger. helse/ velferd 50-20-0011 Samspill mellom gode hjelpere på Fosen Indre Fosen Osen, Ørland, 490 000 kommune Åfjord 50-20-0012 Pasientens helsetjeneste - på vei mot Namsos kommune Forutsetter aktivt og systematisk samarbeid med 1 000 000 brukers sentrum brukerorganisasjoner. 50-20-0014 Tverrfaglig innsats for utsatte barn 0 -6 Oppdal kommune Prioritert gjennom fellesløftet «0-24, utsatte barn og unge». 265 000 år 50-20-0015 Samordnet beredskapsarbeid i Trondheim kommune 400 000 kommunen: Økt trygghet og redusert sårbarhet 50-20-0020 Kompetanseløft for velferdsteknologi og Trondheim kommune Arbeidet skal skje i tett samarbeid med Trøndelagsløftet 1 325 000 tjenesteinnovasjon 50-20-0025 Trøndelagsløftet - velferdsteknologi for Stjørdal kommune Alle Det forutsettes at prosjektet skal sikre at kommunene får 1 200 000 et samlet Trøndelag kompetanse og bistand til å implementere velferdsteknologi. -

Nøkkeltall Og Utfordringer

Nøkkeltall og utfordringer Grunnlag - kommuneplanen for Røros 2016 - 2028 Samfunnsdel Arealdel 02.03.15 1 Innholdsfortegnelse Side 1. Demografi 1.1 Folketall 1950 – 2014 5 1.2 Befolkningssammensetning 31.12.13 5 1.3 Befolkningsprognose 2028 5 1.4 Innvandrerbefolkning 6 1.5 Fødselsoverskudd og flytting 6 1.6 Utfordring folketall og demografi 6 2. Næring 2.1 Bransjestruktur - historisk 7 2.2 Bransjestruktur – dagens 7 2.3 Arbeidsplassutvikling 8 2.4 Nyetableringer, lønnsomhet og vekst 8 2.5 Strategisk næringsplan 2012 – 2022 9 2.6 Reiseliv og turisme 9 2.7 Utfordring næring 12 3. Røros i verden (regionalt, nasjonalt og internasjonalt) 3.1 Pendling 13 3.2 Regionale funksjoner 13 3.3 Interkommunale samarbeidsordninger 14 3.4 Røros nasjonalt og internasjonalt 15 3.5 Utfordring – Røros i verden 16 4. Samferdsel og infrastruktur 4.1 Veitrafikk 17 4.2 Trafikksikkerhetsplan 2013-15 18 4.3 Ulykkesstatistikk 19 4.4 Rørosbanen 20 4.5 Flytrafikk 21 4.6 Utfordring samferdsel og infrastruktur 21 5. Arealbruk 5.1 Arealbruk og arealressurser 22 5.2 Regulert reserve grus- og pukkforekomster 22 5.3 Forurensning ved gamle gruveområder 22 5.4 Bygningsmassen 24 5.5 Utbyggingstakt 24 5.6 Tomtereserve 24 5.7 Utbyggingsmønster 25 5.8 Økonomisk ringvirkning av fritidsbebyggelse 26 5.9 Utfordring arealbruk 26 Side 2 av 70 6. Kultur, idrett og foreningsliv 6.1 Norsk kulturindeks 27 6.2 Kulturarenaer og møteplasser 28 6.3 Barn, ungdom og kultur 28 6.4 Kultur- og idrettsarrangement 29 6.5 Sørsamisk kultur 29 6.6 Immateriell kulturarv 29 6.7 Det frivillige kulturliv 30 6.8 Idrett og friluftsliv 31 6.9 Utfordring kultur, idrett og foreningsliv 32 7.