Mihaela Frunză

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Chemical Romance Co Ty Wiesz O MCR

My Chemical Romance Co ty wiesz o MCR Poziom trudności: Średni 1. Ile członków liczy sobie zespół My Chemical Romance A - 3 B - 4 C - 5 D - 6 2. Z jakiego stanu w USA pochodzi zespół A - Kalifornia B - Nevada C - New Jersey D - Iowa 3. W którym roku powstał zespół? A - 2000 B - 2001 C - 2002 D - 2003 4. Z czyjej iniciatywy powstał zespół? A - Gerarda Waya i Mikeya Waya B - Mikeya Waya i Matta Pelissiera C - Gerarda Waya i Matta Pelissiera D - Mikeya Waya i Raya Toro 5. Kto wymyślił nazwę zespołu? A - Gerard B - Mikey C - Frank D - Ray Copyright © 1995-2021 Wirtualna Polska 6. Gerard jest wokalistą, ale orócz tego kim jeszcze jest? A - jest rysownikiem B - jest aktorem C - jest kucharzem 7. Kto w zespole gra na bassie?? A - Ray B - Bob C - Gerard D - Mikey 8. Kto gra na perkusji?? A - Mikey B - Ray C - Bob D - Frank 9. Kto jest gitarzystą prowadzącym w zepole? A - Mikey B - Bob C - Ray D - Frank 10. Gerard miał duże szanse na podpisanie kontraktu z Cartoon Network o wydanie własnej kreskówki. Jaki tytuł ona nosiła?? A - The Umbrella Academy B - Three Tales of Chemical Romance C - The Breakfast Monkey D - Demolition Lovers 11. Jak miała na imię babcia Mikeya i Gerarda? A - Elena B - Helena C - Alicia D - Rachel Copyright © 1995-2021 Wirtualna Polska 12. Gerard razem z MAttem napisał piosenkę, która inspirowana była tragedią z 11 wrzesnia. Jaki nosi on tytuł?? A - Drowning Lessons B - Early Sunsets Over Monroeville C - Headfirst for Halos D - Skylines and Turnstiles 13. -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 22.05.2015 the GET up KIDS Kommen Im

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 22.05.2015 THE GET UP KIDS kommen im August nach Köln THE GET UP KIDS sind wieder da. Vier Jahre hat es gedauert seit dem letzten Album „There Are Rules“ (das bekanntlich mit den schönen Worten „Das ist sehr gut“ begann) und den Auftritten bei uns. Jetzt haben Matt Pryor, Rob Pope, sein Bruder Ryan, Jim Suptic und James Dewees bestätigt, dass sie wieder gemeinsam unterwegs sein werden. Aber längere Pausen ist man ja gewohnt von den Emo- Helden aus Kansas City. Einerseits wollten auch all die anderen tollen Projekte wie Reggie And The Full Effect, Spoon, My Chemical Romance oder The New Amsterdams, in die die Bandmitglieder verstrickt sind oder waren, vorangetrieben werden. Und natürlich galt es auch, sich an Matt Pryors Soloalben satt zu hören. Jetzt haben THE GET UP KIDS bestätigt, dass 2015 wieder allen gemeinsam gehören soll. Zum Anlass des 20-jährigen Bestehens der Band haben sich die alten Helden wieder zusammengetan und gehen auf Tour, die sie in Deutschland exklusiv nach Köln führt. Das wird eine der seltenen Gelegenheiten sein, dass man die wunderbaren Hooks live erleben darf, die sofort in jeden Song hineinziehen und dieser fast schon „Wohlfühl“- Sound, der sich um den Hörer legt wie eine Decke. Auch weil die Jungs inzwischen auf eine lange und vielfältige Karriere zurückblicken können, weil sie so viel unterschiedliche Musik gespielt haben, weil sie viel gemeinsam und viel getrennt erlebt haben, wird der Jubiläumsauftritt der GET UP KIDS ein absoluter Höhepunkt werden. -

Trump Mideast Plan, Rejected by Palestinians, Faces Dim Prospects

JUMADA ALTHANI 5, 1441 AH THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 2020 28 Pages Max 19º Min 07º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18048 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait addresses UN Human Lebanon political, economic Saif Ali Khan: A star in Thiem stuns Nadal in ‘epic’ 3 Rights Council review session 6 crises fuelling brain drain 22 Bollywood and on Netflix 28 as youngsters gun into semis Trump Mideast plan, rejected by Palestinians, faces dim prospects Abbas throws ‘conspiracy’ in ‘dustbin of history’ • Erdogan slams ‘unacceptable’ proposal JERUSALEM: US President Donald Trump’s long But Trump’s proposals reportedly included no delayed Middle East peace plan won support in Israel Palestinian input and grants Israel much of what it has yesterday but was bitterly rejected by Palestinians fac- sought in decades of international diplomacy, namely Amir attends luncheon at Azayez farm ing possible Israeli annexation of key parts of the West control over Jerusalem as its “undivided” capital, rather Bank. Trump, who unveiled the plan on Tuesday at the than a city to share with the Palestinians. It also offers a White House standing alongside Israel’s Prime Minister US green light for Israel to annex the strategically cru- Benjamin Netanyahu with no Palestinian representa- cial Jordan Valley - which accounts for around 30 per- tives on hand, said his initiative could succeed where cent of the West Bank - as well as other Jewish settle- others had failed. ments in the area. Trump has boasted that his plan will find support but “History knocked on our door last night and gave us most experts believe its unabashed backing of Israel a unique opportunity to apply Israeli law on all of the and tough conditions for the creation of a Palestinian settlements in Judea (and) Samaria,” said Israel’s state mean it is doomed to fail. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC a Study on Collective Identity and Social Movements

RIGHTS CLAIMS THROUGH MUSIC A study on collective identity and social movements Dzeneta Sadikovic Department of Global and Political Studies Human Rights III (MR106S) Bachelor thesis, 15hp 15 ETC, Fall/2019 Supervisor: Dimosthenis Chatzoglakis Abstract This study is an analysis of musical lyrics which express oppression and discrimination of the African American community and encourage potential action for individuals to make a claim on their rights. This analysis will be done methodologically as a content analysis. Song texts are examined in the context of oppression and discrimination and how they relate to social movements. This study will examine different social movements occurring during a timeline stretching from the era of slavery to present day, and how music gives frame to collective identities as well as potential action. The material consisting of song lyrics will be theoretically approached from different sociological and musicological perspectives. This study aims to examine what interpretative frame for social change is offered by music. Conclusively, this study will show that music functions as an informative tool which can spread awareness and encourage people to pressure authorities and make a claim on their Human Rights. Keywords: music, politics, human rights, freedom of speech, oppression, discrimination, racism, culture, protest, social movements, sociology, musicology, slavery, civil rights, African Americans, collective identity List of Contents 1. Introduction p.2 1.1 Topic p.2 1.2 Aim & Purpose p.2 1.3 Human Rights & Music p.3 1.4 Research Question(s) p.3 1.5 Research Area & Delimitations p.3 1.6 Chapter Outline p.5 2. Theory & Previous Research p.6 2.1 Music As A Tool p.6 2.2 Social Movements & Collective Behavior p.8 2.2.1 Civil Rights Movement p.10 3. -

PDF: V121-N12.Pdf

MIT’s The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Partly cloudy, 45°F (7°C) Tonight: Clearing skies, 32°F (0°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Partly cloudy, 43°F (6°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 121, Number 12 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, March 16, 2001 Next House Adopts RBA Pilot Program Half of Dorm’s Freshmen Will Be Selected Over Summer, Live with Advising Groups By Naveen Sunkavally K. Anderson ’02 said a major reason NEWS EDITOR for adopting the program is to make The house government and execu- the dormitory eligible for more tive council of Next House dormitory administrative funds that can be voted unanimously this past Sunday used for residential programming to try out a new residential-based for the entire dormitory. advising program this coming fall. Riordan said that Next House The program will be similar to also chose to try out the program in the one carried out at McCormick order to build a sense of community House last fall. and increase the attention freshmen Under the program, about half of receive to personal issues. While Next House’s freshmen will be pre- there were concerns that the pro- selected through an application gram may create a more classroom- process over the summer and live in like atmosphere in the dormitory, in the vicinity of their associate advis- the end the benefits outweighed the ers, said Next House President costs, Riordan said. MATT YOURST—THE TECH Daniel P. Riordan ’03. The other half About six to seven associate Paula S. Deardon ’03, Maria K. Chan G and Christine Hsu ’03 serve food Saturday at Rosie's of the freshmen living at the dormi- advisers will live in the dormitory, Place, a homeless shelter in Boston. -

THE FASHION Beat Kick Start

THE Beat An eZine for teens...by teens. FASHION BEAT KICK START TO 2007 BEATORIAL Elfwood HIgh MEDIA BEAT NEWS AND MUCH MORE! Kick Start Beatorial Is this person for real? It's that time of the year Cheyne! Time to wear your new clothes, new shoes, listen to your Mp3, play your X-Box™ etc... It's also that time of the year where you can change the path you’re on and the person you’ll be in the future. Didn’t like your attitude So you’ve just came from before the Christmas Holidays? the holidays, and from Now, you can change it by taking having a fight with a Issue 3_Volume_ Be True steps to improve your personality. friend. So what do you do Don’t like your style? Buy new now?You don't want to be clothes, new shoes or get a new the one who goes first and hairstyle. Don’t be afraid to says sorry because you change who you were to didn't do anything,they something that you know everyone started it. Well how about will love, especially yourself. this. Just make eye contact Don’t forget to be yourself, with them or smile, but though. You know the saying: "Be you don't have to talk to who you are"? Well, you can them. But really, why stay have a whole new look and still be in a fight with each other yourself. You don’t have to be when you two can be FASHION Beat something that you don't like. -

It's Not a Fashion Statement

Gielis /1 MASTER THESIS NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES IT’S NOT A FASHION STATEMENT. AN EXPLORATION OF MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY IN CONTEMPORARY EMO MUSIC. Name of student: Claudia Gielis MA Thesis Advisor: Dr. M. Roza MA Thesis 2nd reader: Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Gielis /2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Dr. M. Roza and Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Title of document: It’s Not a Fashion Statement. An exploration of Masculinity and Femininity in Contemporary Emo Music. Name of course: MA Thesis North American Studies Date of submission: 15 August 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Claudia Gielis Gielis /3 Abstract Masculinity and femininity can be performed in many ways. The emo genre explores a variety of ways in which gender can be performed. Theories on gender, masculinity and femininity will be used to analyze both the lyrics and the music videos of these two bands, indicating how they perform gender lyrically and visually. Likewise a short introduction on emo music will be given, to gain a better understanding of the genre and the subculture. It will become clear that the emo subculture allows for men and women to explore their own identity. This is reflected in the music associated to the emo genre as well as their visual representation in their music videos. This essay will explore how both a male fronted band, My Chemical Romance, and a female fronted band, Paramore, perform gender. All studio albums and official music videos will be used to investigate how they have performed gender throughout their career. -

FRANK IERO and the PATIENCE's NEW EP

FRANK IERO and the PATIENCE’S NEW EP “KEEP THE COFFINS COMING” AVAILABLE TODAY U.S. TOUR KICKS OFF IN NOVEMBER September 22, 2017 – Los Angeles, CA – Today, FRANK IERO and the PATIENCE released their new EP, “Keep The Coffins Coming.” The four-track EP was recorded with Frank Iero’s lifelong hero, the iconic Steve Albini (Nirvana, Pixies, PJ Harvey), at Electrical Audio in Chicago, IL. Heartfelt and raw, while still maintaining a fiery punk rock identity, “Keep The Coffins Coming” is a classic Iero album that connects Stomachaches and Parachutes, the band’s debut and sophomore efforts. In light of their accident in Sydney, Australia last year, the guys jokingly call themselves FRANK IERO & ‘THE PATIENTS’ on this release. “Keep The Coffins Coming” is streaming on Apple Music and Spotify and available for purchase on iTunes, Amazon, and Google Play. Yesterday, FRANK IERO and the PATIENCE teamed up with Alternative Press to premiere “No Fun Club,” their new track from the EP. If you were able to catch the band on tour this summer, you may have seen them perform this one live. Check it out HERE. In celebration of “Keep The Coffins Coming,” FRANK IERO and the PATIENCE will head back to the U.S. after their European headline trek for their run of Midwest and East Coast shows, sharing the stage with Descendents, Thursday, and PUP. The tour kicks off in Cleveland, OH on November 17th and wraps with a hometown show in Sayreville, NJ on December 30th. All tickets can be purchased HERE, and a full list of dates is included below. -

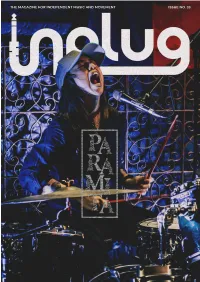

The Magazine for Independent Music and Movement Issue No

THE MAGAZINE FOR INDEPENDENT MUSIC AND MOVEMENT ISSUE NO. 33 ARTISTS 5 THE EARLY EARS, 5 RE:CON, 9 MANILA COUPE D'ETAT, 13 KILLERWEIL, 15 SPOTLIGHT 7 PARAMITA REUNION GIG Photos by Patrick Briones 16 DJ SCENE 24 BAND SCENE 26 GUITARRA & BAJO TUBE MUSIC EVENT PRODUCTION 31 FEATURED MV 33 THE TEAM 4 WRITERS AHMAD TANJI AIMAX MACOY ALFIE VERA MELLA ANNE NICOLE E. LOPEZ ANDREW G. CONTRERAS BENEDICT YABUT BOMBEE DUERME CALVIN MIRALLES CHRISTIANA CARLO YBANEZ JUNE MONGAYA CHOLO ISUNGGA DEXTER KEN AQUINO RIA BAUTISTA DON REX EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDELYNNE MAE ESCARTIN ERVIN R. SALVADOR ESHA BONSOL FROI BATTUING HERB CABRAL HUGINN MUNINN CLARENCE ANTHONY INIGO MORTEL FOUNDER & CEO ISABELLE ROMUALDEZ JAN TERENCE TOLENTINO JANNA LEON JICA LAPENA JOHN BLUES JOHN LEE ARVIN KADIBOY BELARMINO JOHN MATTHEW ACOSTA FILM EDITOR JULIAN SOBREMONTE KHEN CALMA KAMAL MAHTANI JAN TERENCE TOLENTINO KAT CASTRO MUSIC EDITOR KARL KLIATCHKO LYNN JAIRUS MONTILLA MARK ANGELO NOCUM MARK VERZO M. B. SALVANO MIKE TWAIN MIGZ AYUYAO PATRICK BRIONES NIKOS KAZIRES CONTENT WRITER/PHOTOGRAPHER PATRICK BRIONES PEN ISLA ROBERT BESANA FRANCISCO AYUYAO SARAH BUNNY DOMINGUEZ GAMING EDITOR SHIENA CORDERO TERRENCE LYLE TULIO VINA THERESE ARRIESGADO WESLEY VITAN WINA PUANGCO YOGI PAJARILLO PHOTOGRAPHERS CHRIS QUINTANA KIMMY BAROAIDAN RED RIVERA PATRICK BRIONES MAY CEDILLA-VILLACORTA DAWN MONTOYA CONTRIBUTING EDITOR (DJ) GRAPHIC DESIGNER PRESS RELEASE 5 THE EARLY EARS LUMANG PAG-IBIG EP Focus Track: LLDR Release Date: Nov 8, 2019 SGT Platforms: Spotify, Apple Music and iTunes 6 “BAGONG HIMIG, LUMANG PAG-IBIG” The Early Ears is a rock-and-roll band from Quezon City. -

Com As Mãos Sujas De Sangue: Música, Emoções E Romantismos Raphael Bispo 1

Com as mãos sujas de sangue: música, emoções e romantismos Raphael Bispo 1 Resumo O presente artigo tem como proposta analisar as canções produzidas por bandas de rock classificadas de “emo” na atualidade. Resgatando contrastivamente o imaginário romântico do século XVIII – que tem no livro Os sofrimentos do Jovem Werther, de Johann Wolfgang Goethe, uma de suas melhores elaborações –, busca- se compreender mais precisamente as diferentes estratégias e inflexões no processo histórico de elaboração de uma subjetividade interiorizada e autonomizada, típica da modernidade ocidental, tendo como base duas experiências artísticas distintas. Assim, apontando as semelhanças, diferenças e especificidades existentes entre dois momentos de registros estéticos de nossa cultura (a literatura romântica “clássica” de Goethe e a música emo da banda My Chemical Romance), além de se constatar a permanência de uma espécie de “sombra romântica” (DUARTE, 2004) nas artes de hoje, o artigo procura também jogar luz sobre as configurações da vida íntima no Ocidente moderno, mais precisamente sobre como têm operado historicamente nossas experiências amorosas, a partir de narrativas sobre o amor e o self formuladas em momentos históricos específicos. Palavras-chave: emo, amor, romantismo, antropologia das emoções. 1 Doutor em Antropologia Social (Museu Nacional/UFRJ), pesquisador do Centro de Estudos Sociais Aplicados (CESAP/ IUPERJ/ UCAM). Revista Tendências: Caderno de Ciências Sociais. Nº 7, 2013 ISSN: 1677-9460 Com as mãos sujas de sangue: música, emoções e romantismos Abstract This article aims to analyze the songs produced by rock bands classified as “emo” nowadays. Rescuing the romantic imagination of the eighteenth century – which has in the book The Sorrows of Young Werther, by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, one of your best elaborations – we seek to understand more precisely the different strategies and inflections in the historical process of developing a subjectivity internalized and autonomously, typical of western modernity, based on two distinct artistic experiences. -

Loyola Marymount University Presents

Loyola Marymount University ATTIC SALT 2017 Volume 8 Loyola Marymount University Presents Loyola Loyola Marymount University Presents 1 Published by Loyola Marymount University The University Honors Program One LMU Drive, Suite 4400 Los Angeles, CA 90045-2659 All correspondence should be sent to the above address. ©2017 Attic Salt. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design and Layout by Yazmin Delgado-Castellanos [email protected] Printed by DSJ Printing, Inc. in Santa Monica, California 2 ATTIC SALT noun 18th Century: A translation of the Latin Sal Atticum. Graceful, piercing, Athenian wit. Attic Salt is an interdisciplinary journal which accepts submissions in any genre, format, or medium – essays, original research, creative writing, videos, artwork, etc. – from the entire LMU undergraduate and graduate community. Visit www.atticsaltlmu.com for full-length works, past journals, and other information. Attic Salt is published annually in the spring semester. 3 Co-Editors-in-Chief: 2017 Staff Alfredo Hernandez Isabel Ngo Jordan Rehbock Media Editors: Jordan Woods Mary Alverson Editorial Staff: Cameron Bellamoroso Carrie Callaway Alexander Dulak Gillian Ebersole Erin Hood Publication Design: Yazmin Delgado-Castellanos Faculty Advisor: Dr. Alexandra Neel 4 Dear Attic Salt Readers, This year begins a new chapter in the life of the journal as we welcome our new editorial staff. Despite the transition, we still Editors’ garnered more than 140 submissions from the LMU community. We redesigned and launched a new website that documents our past issues and serves as an archive of premier interdisciplinary work. Letter In this year's edition of Attic Salt, the one theme we felt ran through the selected works was a sense of alternative reviewing and editing the numerous submissions we received perspective.