Roe V. Wade: New Questions About Bacdash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1996 Republican Party Primary Election March 12, 1996

Texas Secretary of State Antonio O. Garza, Jr. Race Summary Report Unofficial Election Tabulation 1996 Republican Party Primary Election March 12, 1996 President/Vice President Precincts Reporting 8,179 Total Precincts 8,179 Percent Reporting100.0% Vote Total % of Vote Early Voting % of Early Vote Delegates Lamar Alexander 18,615 1.8% 11,432 5.0% Patrick J. 'Pat' Buchanan 217,778 21.4% 45,954 20.2% Charles E. Collins 628 0.1% 153 0.1% Bob Dole 566,658 55.6% 126,645 55.8% Susan Ducey 1,123 0.1% 295 0.1% Steve Forbes 130,787 12.8% 27,206 12.0% Phil Gramm 19,176 1.9% 4,094 1.8% Alan L. Keyes 41,697 4.1% 5,192 2.3% Mary 'France' LeTulle 651 0.1% 196 0.1% Richard G. Lugar 2,219 0.2% 866 0.4% Morry Taylor 454 0.0% 124 0.1% Uncommitted 18,903 1.9% 4,963 2.2% Vote Total 1,018,689 227,120 Voter Registration 9,698,506 % VR Voting 10.5 % % Voting Early 2.3 % U. S. Senator Precincts Reporting 8,179 Total Precincts 8,179 Percent Reporting100.0% Vote Total % of Vote Early Voting % of Early Vote Phil Gramm - Incumbent 837,417 85.0% 185,875 83.9% Henry C. (Hank) Grover 71,780 7.3% 17,312 7.8% David Young 75,976 7.7% 18,392 8.3% Vote Total 985,173 221,579 Voter Registration 9,698,506 % VR Voting 10.2 % % Voting Early 2.3 % 02/03/1998 04:16 pm Page 1 of 45 Texas Secretary of State Antonio O. -

Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected]

Mississippi College School of Law MC Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Publications 2018 Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control Jonathan Will Mississippi College School of Law, [email protected] I. Glenn Cohen Harvard Law School, [email protected] Eli Y. Adashi Brown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/faculty-journals Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons Recommended Citation 93 Ind. L. J. 499 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personhood Seeking New Life with Republican Control* JONATHAN F. WILL, JD, MA, 1. GLENN COHEN, JD & ELI Y. ADASHI, MD, MSt Just three days prior to the inaugurationof DonaldJ. Trump as President of the United States, Representative Jody B. Hice (R-GA) introducedthe Sanctity of Human Life Act (H R. 586), which, if enacted, would provide that the rights associatedwith legal personhood begin at fertilization. Then, in October 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services releasedits draft strategicplan, which identifies a core policy of protectingAmericans at every stage of life, beginning at conception. While often touted as a means to outlaw abortion, protecting the "lives" of single-celled zygotes may also have implicationsfor the practice of reproductive medicine and research Indeedt such personhoodefforts stand apart anddistinct from more incre- mental attempts to restrictabortion that target the abortionprocedure and those who would perform it. -

Excerpts from Mackinnon/Schlafly Debate

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 4 December 1983 Excerpts from MacKinnon/Schlafly Debate Catharine A. MacKinnon Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Catharine A. MacKinnon, Excerpts from MacKinnon/Schlafly Debate, 1(2) LAW & INEQ. 341 (1983). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol1/iss2/4 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Excerpts from MacKinnon/Schlafly Debate Catharine A. MacKinnon Introduction In the waning months of the most recent attempt to ratify a federal Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), I twice debated Phyllis Schlafly, its leading opponent since 1973 '-once at Stanford Law School', once in Los Angeles.' The argument printed here is from my presentations. I had not been actively involved in the ratification effort, had not spoken on ERA before, and had been persuaded to modify my criticism of its leading interpretation' because I did not want to undercut its chances for approval. I still do not know if it was right to remain silent while the debate on the meaning of sex equality was defined in liberal terms, thereby excluding the issues most central to the status of women and the issues most crucial to most women. Pursuing an untried, if more true, analysis of sex inequality risked losing something that might, once gained, be more meaningfully interpreted. Acquiescence in this calculation overcame the sense that ERA's theory, and strategies based on it, would not only limit its value if won, but insure its loss--a conviction that grew with each setback. -

Marching Through '64

MARCHING THROUGH '64 David J. Garrow Wilson Quarterly Spring 1998, Volume 22, pp. 98-101. Section: Current Books PILLAR OF FIRE: America in the King Years, 1963-65. By Taylor Branch. Simon & Schuster. 746 pp. $30 Pillar of Fire is the second volume of Taylor Branch's projected threevolume history of the American black freedom struggle during the 1950s and 1960s. Ten years ago, Branch published his first volume, Parting the Waters, a richly detailed account of the civil rights movement that covered the years 1954-63 in 922 pages of text. Ending with the aftermath of John F. Kennedy's November 22 assassination, Parting the Waters was intended to be the first of two volumes that would carry the story forward until Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination on April 4, 1968. But Branch changed plans, expanding his history from two volumes to three. Pillar of Fire covers the movement's history from December 1963 until February 1965 in 613 pages of text. Or, to be more precise, about 419 pages of text, for the first 194 pages are devoted to recapitulating much of the 1962-63 history that the author comprehensively treated in Parting the Waters. Should Pillar of Fire be evaluated by itself, or should it be assessed in tandem with Parting the Waters? As King often said, most "either-or" questions-this one included-are best answered with "bothand" responses. Comparing Pillar with Parting raises two questions: why devote almost one-third of Pillar to a reprise of Parting, and why allocate 400-plus pages to essentially just 1964, when all of 1954 through 1963 merited "only" 900? In the author's defense, his readers- whether or not they read Parting the Waters a decade ago-deserve some recapitulation, and 1963 and 1964 almost inarguably were the crucial years of the civil rights movement. -

The New Right

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The New Right Elizabeth Julia Reiley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Reiley, Elizabeth Julia, "The New Right" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625286. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mnnb-at94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW RIGHT 'f A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Elizabeth Reiley 1984 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Elizabeth Approved, May 1984 Edwin H . Rhyn< Satoshi Ito Dedicated to Pat Thanks, brother, for sharing your love, your life, and for making us laugh. We feel you with us still. Presente! iii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................... v ABSTRACT.................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................ s 1 CHAPTER I. THE NEW RIGHT . '............ 6 CHAPTER II. THE 1980 ELECTIONS . 52 CHAPTER III. THE PRO-FAMILY COALITION . 69 CHAPTER IV. THE NEW RIGHT: BEYOND 1980 95 CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION ............... 114 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................. 130 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her appreciation to all the members of her committee for the time they gave to the reading and criticism of the manuscript, especially Dr. -

Ken Guindon Has Written a Well-Documented Account of His Theological Foray Into the Liturgical Churches That Is Both Relevant and Insightful

Ken Guindon has written a well-documented account of his theological foray into the liturgical churches that is both relevant and insightful. His impeccable scholarship and convincing argumentation demands the attention of everyone enamored with Catholicism or Orthodoxy. This is a book that needed to be written, and we should be grateful that one so competent and intelligent has done just that. More than a mental exercise or academic investigation, the substance of this book stems from the crucible of personal experience. Sharing personal lessons from his cross-cultural immersion into sacerdotalism, he attacks no straw men, but carefully and candidly documents ecclesiastical distinctions long recognized, but frequently overlooked. Like David returning from the Philistines, the author has returned to the evangelical fold with a greater appreciation of the gospel. More pioneer than prodigal, the author “came to his senses” with a reaffirmation of faith that is both inspiring and sobering. We welcome him back with honor and kudos for a sensitive critique of Orthodoxy and Catholicism that is both transparent and courageous. —Stephen Brown Professor of Bible and History, Shasta Bible College and Graduate School Because of a number of recent accounts of evangelicals joining the Roman Catholic or the Eastern Orthodox Church, this is an important and much-needed book. Through the examination of church history, theology and Scripture, Ken Guindon shares his spiritual journey and explains why he returned to evangelical Christianity. His study is fair-minded and well-written, and provides a sound defense for his decision. —Edmond C. Gruss, Professor Emeritus, The Master’s College This is a very pertinent book for our time when many prize church history and personal experience above Biblical truth in their search for spiritual vitality. -

Presidential Handwriting File, 1981-1989

PRESIDENTIAL HANDWRITING FILE: PRESIDENTIAL RECORDS: 1981-1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS This collection is available in whole for research use. Some folders may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. PRESIDENTIAL HANDWRITING FILE: PRESIDENTIAL RECORDS: 1981-1989 The Presidential Handwriting File is an artificial collection created by the White House Office of Records Management (WHORM). The Presidential Handwriting File consists of a variety of documents that Ronald Reagan either annotated, edited, or wrote in his own hand. When documents containing the president's handwriting were received at WHORM for filing, the original was placed in the Presidential Handwriting File and arranged by the order received. A photocopy of the document was placed in the appropriate category of the WHORM: Subject File. The first page of the casefile was stamped Handwriting File, indicating the location of the original documents. However, WHORM often failed to indicate on the original documents the original location (i.e. the six digit tracking number, Subject Category Code). The Presidential Handwriting File, as created by the White House, did not contain handwriting found in staff and office files. The Library will be creating a further series of handwriting material from staff and office files. In order to provide better access to the Presidential Handwriting File, the collection has been arranged into six series. Each series is arranged chronologically by the date of the document. Each document has been marked with the appropriate WHORM: Subject File category and a six digit tracking number. -

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Post-Presidential Collection

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Post-Presidential Collection Box Inventory (Materials listed in bold type are available for research) Collections & Box #s Titles Notes Green - Staff Files 1 John Taylor Staff Files- A-E 2 John Taylor Staff Files- F-L 3 John Taylor Staff Files- M-Q 4 John Taylor Staff Files- Q-V 5 John Taylor Staff Files- W-Z 6 Misc. Staff Files- 1975-1979 7 Misc. Staff Files- 1975-1979 8 Staff- RN's 79th & 80th b-day/ 92 Xmas 9 Misc. Nick Ruwe Files 10 Staff- TD's- 1991 11 Staff- TD's- 1992 12 Staff- TD's- 1993-1994 13 Staff- Auctions & Donations 1990 14 Staff- RN Phone Logs 72-91 15 Staff- Autograph Files 91/92/93 16 Staff- Misc. San Clemente Years 17 Misc. Clippings 18 Misc. Clippings 19 Misc. Clippings 20 Misc. Clippings 21 Staff Files- 1992 22 Staff Files- 1992 23 Chron. Files- 1990-1991 24 Staff- Misc. San Clemente Years 25 Staff- Misc. San Clemente Years 26 Staff- Misc. San Clemente Years 27 Memoirs Autograph Files on Index Cards 28 Autograph Index Cards- Mo-Ro 29 Autograph Index Cards- Ro-Tr 30 Autograph Index Cards- Tu-Z 31 Index Cards- Book Files 32 Autograph Index Cards- K-Mi 33 Autograph Index Cards- H-J 34 Autograph Index Cards- Ch-F 35 Autograph Index Cards- A-Ch 36 Staff- Library Bookplates/91-92 Auctions 37 Autograph/Photo Files - 1977 38 Misc. Staff Files- 1980's 39 Staff Files- TD's 1990 40 Misc. Staff Files- San Clemente 41 Misc. Staff Files- San Clemente 42 Misc. -

Does the Fourteenth Amendment Prohibit Abortion?

PROTECTING PRENATAL PERSONS: DOES THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PROHIBIT ABORTION? What should the legal status of human beings in utero be under an originalist interpretation of the Constitution? Other legal thinkers have explored whether a national “right to abortion” can be justified on originalist grounds.1 Assuming that it cannot, and that Roe v. Wade2 and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylva- nia v. Casey3 were wrongly decided, only two other options are available. Should preborn human beings be considered legal “persons” within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, or do states retain authority to make abortion policy? INTRODUCTION During initial arguments for Roe v. Wade, the state of Texas ar- gued that “the fetus is a ‘person’ within the language and mean- ing of the Fourteenth Amendment.”4 The Supreme Court rejected that conclusion. Nevertheless, it conceded that if prenatal “per- sonhood is established,” the case for a constitutional right to abor- tion “collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaran- teed specifically by the [Fourteenth] Amendment.”5 Justice Harry Blackmun, writing for the majority, observed that Texas could cite “no case . that holds that a fetus is a person within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.”6 1. See Antonin Scalia, God’s Justice and Ours, 156 L. & JUST. - CHRISTIAN L. REV. 3, 4 (2006) (asserting that it cannot); Jack M. Balkin, Abortion and Original Meaning, 24 CONST. COMMENT. 291 (2007) (arguing that it can). 2. 410 U.S. 113 (1973). 3. 505 U.S. 833 (1992). 4. Roe, 410 U.S. at 156. Strangely, the state of Texas later balked from the impli- cations of this position by suggesting that abortion can “be best decided by a [state] legislature.” John D. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

(Pdf) Download

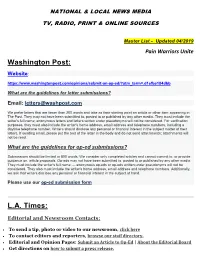

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Social Movement Studies Framing Faith

This article was downloaded by: [Florida State University Libraries] On: 25 January 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 789349894] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Social Movement Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713446651 Framing Faith: Explaining Cooperation and Conflict in the US Conservative Christian Political Movement Deana A. Rohlinger a; Jill Quadagno a a Department of Sociology, Florida State University, Florida, USA To cite this Article Rohlinger, Deana A. and Quadagno, Jill(2009) 'Framing Faith: Explaining Cooperation and Conflict in the US Conservative Christian Political Movement', Social Movement Studies, 8: 4, 341 — 358 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/14742830903234239 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14742830903234239 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.