07 Estep.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Molecular Tools to Guide Management of Invasive Alien

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2015) 1–14 BIODIVERSITY Using molecular tools to guide RESEARCH management of invasive alien species: assessing the genetic impact of a recently introduced island bird population J. van de Crommenacker1,2*, Y. X. C. Bourgeois3, B. H. Warren4, H. Jackson2, F. Fleischer-Dogley1, J. Groombridge2 and N. Bunbury1 1Seychelles Islands Foundation, La Ciotat ABSTRACT Building, Mont Fleuri, Mahe, Victoria, Aim Biological invasions are a major threat to island biodiversity and are Seychelles, 2Durrell Institute of Conservation responsible for a large proportion of species declines and extinctions world- and Ecology (DICE), School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, wide. The process of hybridization between invasive and native species is a Marlowe Building, Canterbury, Kent, UK, major factor that contributes to the loss of endemic genetic diversity. The issue 3Zoologisches Institut, Evolutionsbiologie, of hybridization is often overlooked in the management of introduced species A Journal of Conservation Biogeography University of Basel, Vesalgasse 1, 4051 Basel, because morphological evidence of hybridization may be difficult to recognize Switzerland, 4Institute of Systematic Botany, in the field. Molecular techniques, however, facilitate identification of specific University of Zurich, Zollikerstrasse 107, hybridization events and assessment of the direction and timing of introgres- 8008 Zurich, Switzerland sion. We use molecular markers to track hybridization in a population of an island endemic bird, the Aldabra fody (Foudia aldabrana), following the recent discovery of a co-occurring population of non-native Madagascar fodies (Foudia madagascariensis). Location Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles. Methods We combine phylogenetic analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear markers to assess whether hybridization has occurred between F. -

Increasing Use of Exotic Forestry Tree Species As Refuges from Nest Predation by the Critically Endangered Mauritius Fody Foudia Rubra a Ndrew C Ristinacce,Richard A

Increasing use of exotic forestry tree species as refuges from nest predation by the Critically Endangered Mauritius fody Foudia rubra A ndrew C ristinacce,Richard A. Switzer,Ruth E. Cole,Carl G. Jones and D iana J. Bell Abstract The population of the Critically Endangered threatened bird species (Butchart et al., 2006). Rats are the Mauritius fody Foudia rubra fell by 55% over 1975–1993 most widespread and successful invaders on islands, capa- because of habitat destruction and predation. The species ble of causing dramatic declines in local bird populations was believed to be dependent on a small grove of intro- (Penloup et al., 1997; Towns et al., 2006). The Mauritian duced, non-invasive Cryptomeria japonica trees that of- avifauna has also been adversely affected by introduced fered protection from nest predation. We investigated the crab-eating macaques Macaca fascicularis, a predator rarely current population size and distribution of the fody and found as an exotic pest species on oceanic islands (Johnson compared nesting success in forestry plantations to that of & Stattersfield, 1990). a released population on an offshore island. The popula- The population size of the Mauritius fody Foudia rubra, tion size on the mainland has remained stable over the past categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List 10 years, with increases in pine Pinus spp. plantations, but (IUCN, 2007), decreased by 55%over1975–1993 from an esti- continues to decline in areas of predominantly native vege- mated 247–260 to 104–120 pairs, with a parallel contraction 2 2 tation. Only 16% of pairs found were estimated to nest in in extent of occurrence from c. -

MADAGASCAR TRIP REPORT Aug.-‐Sept 2012 John Clark

MADAGASCAR TRIP REPORT Aug.-Sept 2012 John Clark ([email protected]) Our London friends, Dick and Liz Turner, Mary Ward-Jackson and I spent almost 4 weeks in Madagascar. Our primary focus was Birds, But we were also interested in nature more Broadly and culture. The tour was excellently prepared By our guide, Fanomezantsoa Andrianirina (Fano) – who was a perfect guide as well as Being great fun to travel with. The trip was excellent and we ended up seeing 122 of the endemic (and endemic Breeding) Birds of Madagascar, plus 54 non-endemics. Fano was not only an excellent Bird-guide himself, But he had lined up local guides in most of the locations – most of whom were terrific (especially, perhaps, Jaqui in Ampijoroa). Fano is doing much to help develop these local guides as more experienced and confident bird-guides in their own right. The logistics and places to stay were excellent – well, as excellent as an inevitaBle dependence on Madagascar Air permits! (They don’t call it Mad. Air for nothing; it is quite the worst airline I have ever had to use!). Fano’s drivers were also terrific (and keen budding birders!) So our main advice, for those planning a birding (or indeed broader nature/wildlife) trip to Mad. is to use Fano if at all possible. He was totally professional, accurate, dogged, scientifically knowledgeaBle about the Bird, mammals and other species and became a good friend. He can Be contacted By email on [email protected], phone: (+261)32 02 017 91 or website: www.madagascar-funtourguide.com If you want more info on the trip, please email me, and if you’d like to see some of our photos go to: https://picasaweb.google.com/104472367063381721824/Madagascar2012?authkey=Gv1sRgcJH0nYK-wenN9AE# Itinerary Aug. -

The Firefronted Bishop (Euplectes Diadematus)

Focus on African Finches: The Firefronted Bishop (Euplectes diadematus) byJosefH. Lindholm, III Keeper WBirds Fort Worth Zoological Park "So! Now we're a pet store? Well At the same time, we were also mak marked contrast to its close, but gimme a couple of those $3.95 spe ing plans of an entirely different smaller and less spectacular relatives, cials!" Doug Pernikoff, our zoo veter nature. While still Assistant Curator, the West Nile Red Bishop (or Orange inarian, never misses an opportunity long before his promotion in 1991, Weaver) (E. franciscanaJ and the to be clever, and an opportunity it Chris Brown, our Curator of Birds, Yellow-crowned (or Napoleon) certainly was. In the early evening of was keenly interested in establishing Bishop (E. afer), the two most fre January 23, 1992, a hundred birds of long-term breeding programs. In quently encountered weavers in pri sixteen species arrived simultaneously December, 1991, while making vate collections. I have never seen a at our zoo hospital, filling a quarantine arrangements for birds for the new Black-winged Bishop in a pet store, room improvised from a large animal primate building, we were told repeat and only once in a dealer's com holding cage, now hung with rows of edly by prospective suppliers, that a pound. The only zoos where I've seen shiny new bird cages. long-talked-about embargo by com any were the Bronx Zoo and Cincin mercial airlines on shipping birds nati, and the only one I ever saw in As our assembled bird staff hastily from Africa was imminent. -

Download Download

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Paper Editor: Les G. Underhill OVERVIEW OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE WEAVERS H. Dieter Oschadleus Recommended citation format: Oschadleus HD 2016. Overview of the discovery of the weavers. Biodiversity Observations 7. 92: 1–15. URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=285 Published online: 13 December 2016 – ISSN 2219-0341 – Biodiversity Observations 7.92: 1–15 1 TAXONOMY Currently, 117 living species of weavers in the Ploceidae family are recognised. Hoyo et al. OVERVIEW OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE WEAVERS (2010) listed 116 species but Safford & Hawkins (2013) split the Aldabra Fody Foudia H. Dieter Oschadleus aldabrana from the Red- headed Fody Foudia Animal Demography Unit, Department of Biological Sciences, eminentissima. Dickinson & University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701 South Africa Christidis (2014) also listed 117 species. -

Madagascar 17- 30 November 2017

Madagascar 17- 30 november 2017 Birds (153 species) ♫ = only heard E = Endemic White-faced Whistling Duck Madagascan Rail E Red-breasted Coua E Blue Vanga E Meller's Duck E White-throated Rail Red-fronted Coua E Red-tailed Vanga E Red-billed Teal Common Moorhen Green-capped Coua E Red-shouldered Vanga E Hottentot Teal Red-knobbed Coot Running Coua E Nuthatch Vanga E Madagascan Partridge E Grey Plover Crested Coua E Hook-billed Vanga E Little Grebe Kittlitz's Plover Verreaux's Coua E Helmet Vanga E Madagascan Grebe E Common Ringed Plover Blue Coua E Rufous Vanga E Red-tailed Tropicbird Madagascan Plover E Malagasy Coucal E White-headed Vanga E Grey Heron Three-banded Plover Rainforest Scops Owl Pollen's Vanga E Humblot's Heron E Crab-plover Madagascan Owl E Ward's Flycatcher E Purple Heron Black-winged Stilt White-browed Hawk-Owl E Crossley's Vanga ♫ E Great Egret Common Sandpiper Madagascan Nightjar E Madagascan Cuckooshrike E Dimorphic Egret Green Sandpiper Collared Nightjar E Crested Drongo E Black Heron Common Greenshank Madagascan Spinetail E Malagasy Paradise Flycatcher E Western Cattle Egret Whimbrel Malagasy Black Swift E Pied Crow Squacco Heron Ruddy Turnstone Little Swift Madagascan Lark E Malagasy Pond Heron Sanderling African Palm Swift Brown-throated Martin Striated Heron Curlew Sandpiper Malagasy Kingfisher E Mascarene Martin Black-crowned Night Heron Madagascan Snipe E Madagascan Pygmy Kingfisher E Barn Swallow Madagascan Ibis E Madagascan Buttonquail E Olive Bee-eater Malagasy Bulbul E Hamerkop Madagascan Pratincole E Broad-billed -

Sexual Selection of Multiple Handicaps in the Red‐Collared Widowbird: Female Choice of Tail Length but Not Carotenoid Display

Evolution, 55(7), 2001, pp. 1452±1463 SEXUAL SELECTION OF MULTIPLE HANDICAPS IN THE RED-COLLARED WIDOWBIRD: FEMALE CHOICE OF TAIL LENGTH BUT NOT CAROTENOID DISPLAY SARAH R. PRYKE,1,2 STAFFAN ANDERSSON,3,4 AND MICHAEL J. LAWES1,5 1School of Botany and Zoology, University of Natal, Private Bag X01, Scottsville 3209, South Africa 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Zoology, GoÈteborg University, Box 463, SE-405 30 GoÈteborg, Sweden 4E-mail: [email protected] 5E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Although sexual selection through female choice explains exaggerated male ornaments in many species, the evolution of the multicomponent nature of most sexual displays remains poorly understood. Theoretical models suggest that handicap signaling should converge on a single most informative quality indicator, whereas additional signals are more likely to be arbitrary Fisherian traits, ampli®ers, or exploitations of receiver psychology. Male nuptial plumage in the highly polygynous red-collared widowbird (Euplectes ardens) comprises two of the commonly advocated quality advertisements (handicaps) in birds: a long graduated tail and red carotenoid coloration. Here we use multivariate selection analysis to investigate female choice in relation to male tail length, color (re¯ectance) of the collar, other aspects of morphology, ectoparasite load, display rate, and territory quality. The order and total number of active nests obtained are used as measures of male reproductive success. We demonstrate a strong female preference and net sexual selection for long tails, but marginal or no effects of color, morphology, or territory quality. Tail length explained 47% of male reproductive success, an unusually strong ®tness effect of natural ornament variation. -

Download Report

Tel office: +264 61 379 513 Physical address: Postal address: Fax office: +264 61 22 5371 Agricultural Boards’ Building PO Box 5096 E-mail: [email protected] 30 David Hosea Meroro Road Ausspannplatz Website: www.nab.com.na Windhoek Windhoek Constituted by Act 20 of 1992 Creating a marketing environment that is conducive to growing and processing crops in Namibia AGRONOMY AND HORTICULTURE MARKET DEVELOPMENT DIVISION RESEARCH AND POLICY DEVELOPMENT SUBDIVISION QUELEA BIRDS CONTROL MEASURES IN NAMIBIA: TRIAL USING AGRI-FREQUENCY METHOD 2019 Quelea quelea birds control - Research Report 2019 Page 0 of 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ 2 2. OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................. 2 3. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 2 4. DESCRIPTION............................................................................................................... 2 5. BREEDING .................................................................................................................... 3 6. HABITAT ....................................................................................................................... 4 7. FEEDING ....................................................................................................................... 4 8. POPULATION .............................................................................................................. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Hybridization Between Madagascan Red Fody Foudia Madagascariensis and Seychelles Fody Foudia Sechellarum on Aride Island, Seychelles

Bird Conservation International (1997) 7:1-6 Hybridization between Madagascan Red Fody Foudia madagascariensis and Seychelles Fody Foudia sechellarum on Aride Island, Seychelles ROBERT S. LUCKING Summary On islands where populations of the endemic Seychelles Fody Foudia sechellarum and the introduced Madagascan Red Fody F. madagascariensis coexist, previous studies have concluded that the two species are reproductively isolated. On Aride Island, Seychelles, one female F. sechellarum became established within a population of F. madagascariensis and produced at least two hybrid offspring. This paper describes the first known case of hybridization between the two species and highlights the possible biological consequences. Introduction , The Ploceine genus Foudia is endemic to the western Indian Ocean and is represented by five extant species. Within the granitic islands of the Seychelles, two species of Foudia are present. The Madagascan Red Fody F. madagascariensis was introduced from Madagascar to the granitic Seychelles last century and is now one of the most abundant and widespread passerine bird species in the islands (Penny 1974). The endemic Seychelles Fody F. sechellarum is confined as a breeding species to the islands of Fregate, Cousin and Cousine in the granitic group of islands. In 1965, the Bristol Seychelles Expedition introduced five birds to D'Arros in the Amirantes (Gaymer et al. 1969) but this population was thought to have died out until an estimated 100 pairs were discovered on the island in May 1995 (A. Skerrett pers. comm. ). Historically, the Seychelles Fody was also found on Praslin, La Digue, Marianne and Aride (Collar and Stuart 1985). The species's extinction on these islands has been attributed to a combination of deforestation and the introduction of rats Rattus sp., mice Mus musculus and cats Felis domesticus (Crook 1961) although Diamond and Feare (1980) considered habitat change to have had a minor effect as Fregate Island holds four endemic bird species, is predator free and yet the vegetation is 95% exotic. -

This Regulation Shall Enter Into Force on the Day Of

19 . 10 . 88 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 285 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC ) No 3188 / 88 of 17 October 1988 amending Council Regulation ( EEC ) No 3626 / 82 on the implementation in the Community of the Convention on international trade in endangered species of wild fauna und flora THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Whereas the measures provided for in this Regulation are in accordance with the opinion of the Committee on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora , Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community , HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC ) No 3626 / 82 Article 1 of 3 December 1982 on the implementation in the Corrimunity of the Convention on international trade in Appendix III of Annex A to Regulation ( EEC ) No 3626 / 82 endangered species of wild fauna and flora ( J ), as last is hereby replaced by the Annex to this Regulation . amended by Regulation ( EEC ) No 869 / 88 ( 2 ), and in particular Article 4 , thereof, Article 2 Whereas alterations were made to Appendix III to the This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Convention ; whereas Appendix III of Annex A to Communities . Regulation ( EEC ) No 3626 / 82 should now be amended to incorporate the amendments accepted by the Member States parties to the abovementioned Convention ; It shall apply from 21 September 1988 . This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States . -

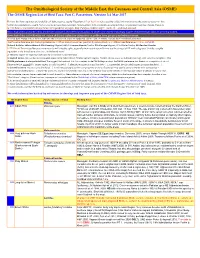

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed.