Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Dominique Townsend All rights reserved ABSTRACT Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend This dissertation investigates the relationships between Buddhism and culture as exemplified at Mindroling Monastery. Focusing on the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, I argue that Mindroling was a seminal religio-cultural institution that played a key role in cultivating the ruling elite class during a critical moment of Tibet’s history. This analysis demonstrates that the connections between Buddhism and high culture have been salient throughout the history of Buddhism, rendering the project relevant to a broad range of fields within Asian Studies and the Study of Religion. As the first extensive Western-language study of Mindroling, this project employs an interdisciplinary methodology combining historical, sociological, cultural and religious studies, and makes use of diverse Tibetan sources. Mindroling was founded in 1676 with ties to Tibet’s nobility and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s newly centralized government. It was a center for elite education until the twentieth century, and in this regard it was comparable to a Western university where young members of the nobility spent two to four years training in the arts and sciences and being shaped for positions of authority. This comparison serves to highlight commonalities between distant and familiar educational models and undercuts the tendency to diminish Tibetan culture to an exoticized imagining of Buddhism as a purely ascetic, world renouncing tradition. -

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

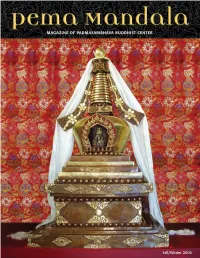

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

K. Lim Studies in Later Buddhist Iconography In

K. Lim Studies in later Buddhist iconography In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 120 (1964), no: 3, Leiden, 327-341 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/03/2021 12:58:57AM via free access STUDIES IN LATER BUDDHIST ICONOGRAPHY 1. The Vajradhütu-mandala of Nganjuk n interesting study by F. D. K. Bosch on Buddhist iconography was published in 1929 under the title: Buddhistische Gegevens uitA Balische Handschriften,1 in which by manuscripts are meant: I. the Sang hyang Nagabayusütra 2; II. the Kalpabuddha.3 No. 1 is a prayer to the five Jinas mentioning their names with their corresponding jnanas, colours, mudras, simhasanas, paradises, krodha-forms, Taras, Bodhisattvas and mystic syllables. The Kalpabuddha (in Old-Javanese) contains an enumeration of the principal qualities and characteristics of the five Jinas which for the greater part correspond with those of the Sang hyang Nagabayusütra. However, the names of their krodha- forms are lacking, instead of which one finds the names of their emblems (sanjatas = weapons), of their cosmic places, of their saktis, of the sense-organs, and of the places in the body having relations with the quintet. Both mss. are closely allied and treat on the same subject, except some points in which they complement each other. In comparing them with the Sang hyang KamahaySnikan Bosch stated that both mss. are independant of this text, and that, where other sources keep silent, they contain the complete list of the paradises of the five Jinas, viz. Sukhavatï of Amitabha, Abhirati of Aksobhya, Ratnavatï of Ratnasam- bhava, Kusumitaloka of Amoghasiddha and Sahavatiloka of Vairocana. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

A Sorrowful Song to Palden Lhamo Kün-Kyab Tro

A SORROWFUL SONG TO PALDEN LHAMO KÜN-KYAB TRO- DREL A PRAISE BY HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA Expanse of great bliss, all-pervading, free from elaborations, with either angry or desirous forms related to those to be subdued. You overpower the whole apparent world, samsara and nirvana. Sole mother, lady victorious over the three worlds, please pay attention here and now! During numberless eons, By relying upon and accustoming yourself to the extensive conduct of the bodhisattvas, which others find difficult to follow, you obtained the power of the sublime vajra enlightenment; loving mother, you watch and don’t miss the [right] time. The winds of conceptuality dissolve into space. Vajra-dance of the mind that produces all the animate and inanimate world, as the sole friend yielding the pleasures of existence and peace, having conquered them all, you are well praised as the triumphant mother. By heroically guarding the Dharma and dharma- holders, with the four types of actions, flashing like lightning, You soar up openly, like the full moon in the midst of a garland of powerful Dharma protectors. When from the troublesome nature of this most degenerated time The hosts of evil omens — desire, anger, ignorance — increasingly rise, even then your power is unimpeded, sharp, swift and limitless. How wonderful! Longingly remembering you, O Goddess, from my heart, I confess my broken vows and satisfy all your pleasures. Having enthroned you as the supreme protector, greatest among the great, accomplish your appointed tasks with unflinching energy! Fierce protecting deities and your retinues who, in accordance with the instructions of the supreme siddha, the lotus-born vajra, and by the power of karma and prayers, have a close connection as guardians of Tibet, heighten your majesty and increase your powers! All beings in the country of Tibet, although destroyed by the enemy and tormented by unbearable suffering, abide in the constant hope of glorious freedom. -

Pre-Proto-Iranians of Afghanistan As Initiators of Sakta Tantrism: on the Scythian/Saka Affiliation of the Dasas, Nuristanis and Magadhans

Iranica Antiqua, vol. XXXVII, 2002 PRE-PROTO-IRANIANS OF AFGHANISTAN AS INITIATORS OF SAKTA TANTRISM: ON THE SCYTHIAN/SAKA AFFILIATION OF THE DASAS, NURISTANIS AND MAGADHANS BY Asko PARPOLA (Helsinki) 1. Introduction 1.1 Preliminary notice Professor C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky is a scholar striving at integrated understanding of wide-ranging historical processes, extending from Mesopotamia and Elam to Central Asia and the Indus Valley (cf. Lamberg- Karlovsky 1985; 1996) and even further, to the Altai. The present study has similar ambitions and deals with much the same area, although the approach is from the opposite direction, north to south. I am grateful to Dan Potts for the opportunity to present the paper in Karl's Festschrift. It extends and complements another recent essay of mine, ‘From the dialects of Old Indo-Aryan to Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian', to appear in a volume in the memory of Sir Harold Bailey (Parpola in press a). To com- pensate for that wider framework which otherwise would be missing here, the main conclusions are summarized (with some further elaboration) below in section 1.2. Some fundamental ideas elaborated here were presented for the first time in 1988 in a paper entitled ‘The coming of the Aryans to Iran and India and the cultural and ethnic identity of the Dasas’ (Parpola 1988). Briefly stated, I suggested that the fortresses of the inimical Dasas raided by ¤gvedic Aryans in the Indo-Iranian borderlands have an archaeological counterpart in the Bronze Age ‘temple-fort’ of Dashly-3 in northern Afghanistan, and that those fortresses were the venue of the autumnal festival of the protoform of Durga, the feline-escorted Hindu goddess of war and victory, who appears to be of ancient Near Eastern origin. -

2019 YAMANTAKA Drubchen at Drikung Rinchen Choling Led By

2019 YAMANTAKA Drubchen at Drikung Rinchen Choling Led by: His Eminance Garchen Rinpoche, Ven. Lama Thupten Nima & Garchen Institute lamas Hosted by: Drikung Rinchen Choling at 4048 E. Live Oak Avenue, Arcadia, CA 91006 Date: March 28 (Thursday) to April 3 (Wednesday) Registration by e-mail: send registration form to [email protected] on Saturday, 12/15/2018 starting at 9:00 am Los Angeles time. Any e-mails that arrive earlier than 9:00 am Los Angeles time on 12/15 will not be accepted. Fee: US $380 Please note that only ONE PERSON may register PER e-mail. A separate e-mail message must be made for each person wishing to register, including for each member of a married couple. If you are unable to send in your registration via email, you may have someone else e-mail on your behalf. Once the drubchen is full, a waiting list will be created in the same way. We plan to contact you by the end of Monday, December 22, to let you know if you receive a place in the drubchen or are on the waiting list. The fee for participating in the drubchen is $380, and a NONREFUNDABLE and NONTRANSFERABLE deposit of $180 is due by January 4, 2019 to hold your place. Please make the check payable to Rinchen Choling and mail it to: 4048 E. Live Oak Ave., Arcadia, CA 91006. The balance should be paid by March 18 before the start of the drubchen. VERY IMPORTANT: If you have not participated in the Yamantaka Drubchen led by Garchen Rinpoche or the Garchen Institute lamas before, the following information must also be provided at the time you register: A reference from a monastic member with knowledge of the Yamantaka Drubchen who knows you and your practice well and will vouch for your ability to complete the drubchen practice. -

Transcendent Spirituality in Tibetan Tantric Buddhism Bruce M

RETN1313289 Techset Composition India (P) Ltd., Bangalore and Chennai, India 4/3/2017 ETHNOS, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2017.1313289 5 Self-possessed and Self-governed: Transcendent Spirituality in Tibetan Tantric Buddhism Bruce M. Knauft 10 Emory University, USA ABSTRACT Among Tibetan Buddhist tantric practitioners, including in the U.S., visualisation and incorporation of mandala deities imparts a parallel world against which conventional 15 reality is considered impermanent and afflicted. Tantric adepts aspire through meditation, visualisation, and mind-training to dissolve normal selfhood and simultaneously embrace both ‘conventional’ and ‘ultimate’ reality. Ethics of compassion encourage efficient reengagement with conventional world dynamics rather than escaping them: the transcendental ‘non-self’ is perceived to inform efficient and compassionate waking consciousness. Transformation of subjective 20 ontology in tantric self-possession resonates with Foucault’s late exploration of ethical self-relationship in alternative technologies of subjectivation and with Luhrmann’s notion of transcendent spiritual absorption through skilled learning and internalisation. Incorporating recent developments in American Tibetan Buddhism, this paper draws upon information derived from a range of scholarly visits to rural and urban areas of the Himalayas, teachings by and practices with contemporary 25 Tibetan lamas, including in the U.S., and historical and philosophical Buddhist literature and commentaries. CE: PV QA: Coll: KEYWORDS Tibetan Buddhism; tantra; spirituality; selfhood; ontology; spirit possession 30 This paper considers dynamics of transcendent spirituality in a cultural context that has often remained outside received considerations of spirit possession: Tibetan Buddhist tantras. I am concerned especially the Sarma or ‘new translation’ generation and com- pletion stage practices associated with highest yoga tantra in Tibetan Buddhist Gelug and Kagyü sects. -

The Dalai Lama

THE INSTITUTION OF THE DALAI LAMA 1 THE DALAI LAMAS 1st Dalai Lama: Gendun Drub 8th Dalai Lama: Jampel Gyatso b. 1391 – d. 1474 b. 1758 – d. 1804 Enthroned: 1762 f. Gonpo Dorje – m. Jomo Namkyi f. Sonam Dargye - m. Phuntsok Wangmo Birth Place: Sakya, Tsang, Tibet Birth Place: Lhari Gang, Tsang 2nd Dalai Lama: Gendun Gyatso 9th Dalai Lama: Lungtok Gyatso b. 1476 – d. 1542 b. 1805 – d. 1815 Enthroned: 1487 Enthroned: 1810 f. Kunga Gyaltsen - m. Kunga Palmo f. Tenzin Choekyong Birth Place: Tsang Tanak, Tibet m. Dhondup Dolma Birth Place: Dan Chokhor, Kham 3rd Dalai Lama: Sonam Gyatso b. 1543 – d. 1588 10th Dalai Lama: Tsultrim Gyatso Enthroned: 1546 b. 1816 – d. 1837 f. Namgyal Drakpa – m. Pelzom Bhuti Enthroned: 1822 Birth Place: Tolung, Central Tibet f. Lobsang Drakpa – m. Namgyal Bhuti Birth Place: Lithang, Kham 4th Dalai Lama: Yonten Gyatso b. 1589 – d. 1617 11th Dalai Lama: Khedrub Gyatso Enthroned: 1601 b. 1838– d. 1855 f. Sumbur Secen Cugukur Enthroned 1842 m. Bighcogh Bikiji f. Tseten Dhondup – m. Yungdrung Bhuti Birth Place: Mongolia Birth Place: Gathar, Kham 5th Dalai Lama: 12th Dalai Lama: Trinley Gyatso Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso b. 1856 – d. 1875 b. 1617 – d. 1682 Enthroned: 1860 Enthroned: 1638 f. Phuntsok Tsewang – m. Tsering Yudon f. Dudul Rapten – m. Kunga Lhadze Birth Place: Lhoka Birth Place: Lhoka, Central Tibet 13th Dalai Lama: Thupten Gyatso 6th Dalai Lama: Tseyang Gyatso b. 1876 – d. 1933 b. 1683 – d. 1706 Enthroned: 1879 Enthroned: 1697 f. Kunga Rinchen – m. Lobsang Dolma f. Tashi Tenzin – m. Tsewang Lhamo Birth Place: Langdun, Central Tibet Birth Place: Mon Tawang, India 14th Dalai Lama: Tenzin Gyatso 7th Dalai Lama: Kalsang Gyatso b. -

Yamantaka Drubchen

DRIKUNG GARCHEN INSTITUT e.V. Yamantaka Drubchen The Yamantaka Drubchen differs in many ways from other drubchens and practices. In the past in Tibet this drubchen was only open to those who had taken vows of ordination and who had completed the common preliminary practices (Ngöndro) as well as the particular preliminary practices of Yamantaka. General Rules: The deity practiced in this drubchen is very wrath- and powerful, and therefore the practice must be done with great care. It is a very rigorous practice with strict rules of conduct. The sole purpose of these rules is to avoid being engaged in accustomed daily distraction during the drubchen and to direct the mind inwardly. To keep to the rules will create a very helpful atmosphere for all participants and moreover an immeasurable benefit for the sake of all sentient beings and the entire world. It is especially important that everybody takes care not to disturb anybody through their behavior and to ignore any disturbance by others, so anger cannot arise. Please be aware, that one single moment of negative emotions, especially anger, destroys the merit of the entire group and the entire drubchen. Therefore it is of utmost importance to adhere to the guidelines as closely as possible and to keep to the rules. Once the practice has begun nobody can leave the house and nobody will be allowed to enter thereafter. Nobody may leave the temple for any other reason than to go to the toilet, for the three daily meals and to sleep during the nightshifts. You cannot leave the house even if you don’t feel well or health problems arise (except for an emergency situation), as the Yamantaka Mandala must not be broken.