Qian Qianyi's Reflections on Yellow Mountain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Tourism in China

6th UNWTO Executive Training Program, Bhutan Sustainable Tourism Observatories and Cases in China Prof. BAO Jigang, Ph. D Assistant President, Dean of School of Tourism Management, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, P. R. China Email:[email protected] 25th - 28th, June, 2012 Content Part I: Observatories for Sustainable Tourism Development in China; Part II: Indicators for Sustainable Tourism Development in Yangshuo, China; Part III: Chinese Sustainable Tourism Cases(Some positive and negative examples) Observatories for Sustainable Part I Tourism Development in China Introduction The Observatory for Sustainable Tourism development in China In July 2005, the workshop of “UNWTO Indictors for Sustainable Tourism” was held in Yangshuo, Guilin, China. Yangshou Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development was founded in 2005. The conference of UNWTO indicators for Sustainable Tourism The Destinations as Cases for Sustainable Tourism Development in China In March 2008, the Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain was established. Opening Ceremony of the Observatory for Sustainable Centre for Tourism Planning & Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain Research , Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, takes the responsibility to monitor the indicators for sustainable tourism in Huangshan Mountain . Observatory for Sustainable Tourism Development in Huangshan Mountain The Destinations as Cases for Sustainable Tourism Development in China Collaboration Agreement between UNWTO and Sun Yat-Sen University -

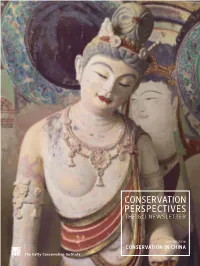

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION MOUNT SANQINGSHAN NATIONAL PARK (CHINA) – ID No. 1292

WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION MOUNT SANQINGSHAN NATIONAL PARK (CHINA) – ID No. 1292 1. DOCUMENTATION i) Date nomination received by IUCN: April 2007 ii) Additional information offi cially requested from and provided by the State Party: IUCN requested supplementary information on 14 November 2007 after the fi eld visit and on 19 December 2007 after the fi rst IUCN World Heritage Panel meeting. The fi rst State Party response was offi cially received by the World Heritage Centre on 6 December 2007, followed by two letters from the State Party to IUCN dated 25 January 2008 and 28 February 2008. iii) UNEP-WCMC Data Sheet: 11 references (including nomination document) iv) Additional literature consulted: Dingwall, P., Weighell, T. and Badman, T. (2005) Geological World Heritage: A Global Framework Strategy. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; Hilton-Taylor, C. (compiler) (2006) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; IUCN (ed.) (2006) Enhancing the IUCN Evaluation Process of World Heritage Nominations: A Contribution to Achieving a Credible and Balanced World Heritage List. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland; Management Committee (2007) Abstract of the Master Plan of Mount Sanqingshan National Park. Mount Sanqingshan National Park; Management Committee (2007) Mount Sanqingshan International Symposium on Granite Geology and Landscapes. Mount Sanqingshan National Park; Migon, P. (2006) Granite Landscapes of the World. Oxford University Press; Migon, P. (2006) Sanqingshan – The Hidden Treasure of China. Available online; Peng, S.L., Liao, W.B., Wang, Y.Y. et al. (2007) Study on Biodiversity of Mount Sanqingshan in China. Science Press, Beijing; Shen, W. (2001) The System of Sacred Mountains in China and their Characteristics. -

3 Days Datong Pingyao Classical Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 3 days Datong Pingyao classical tour https://windhorsetour.com/datong-pingyao-tour/datong-pingyao-classical-tour Datong Pingyao Exploring the highlights of Datong and Pingyao's World Culture Heritage sites gives you a chance to admire the superb artistic attainments of the craftsmen and understand the profound Chinese culture in-depth. Type Private Duration 3 days Theme Culture and Heritage, Family focused, Winter getaways Trip code DP-01 Price From € 304 per person Itinerary This is a 3 days’ culture discovery tour offering the possibility to have a glimpse of the profound culture of Datong and Pingyao and the outstanding artistic attainments of the craftsmen of ancient China in a short time. The World Cultural Heritage Site - Yungang Grottoes, Shanhua Monastery, Hanging Monastery, as well as Yingxian Wooden Pagoda gives you a chance to admire the rich Buddhist culture of ancient China deeply. The Pingyao Ancient City, one of the 4 ancient cities of China and a World Cultural Heritage site, displays a complete picture of the prosperity of culture, economy, and society of the Ming and Qing Dynasties for tourists. Day 01 : Datong arrival - Datong city tour Arrive Datong in the early morning, your experienced private guide, and a comfortable private car with an experienced driver will be ready (non-smoking) to serve for your 3 days ancient China discovery starts. The highlights today include Shanhua Monastery, Nine Dragons Wall, as well as Yungang Grottoes. Shanhua Monastery is the largest and most complete existing monastery in China. The Nine Dragons Wall in Datong is the largest Nine Dragons Wall in China, which embodies the superb carving skills of ancient China. -

Chinese Religious Art

Chinese Religious Art Chinese Religious Art Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky LEXINGTON BOOKS Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK Published by Lexington Books A wholly owned subsidiary of Rowman & Littlefield 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom Copyright © 2014 by Lexington Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Karetzky, Patricia Eichenbaum, 1947– Chinese religious art / Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7391-8058-7 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-7391-8059-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-7391-8060-0 (electronic) 1. Art, Chinese. 2. Confucian art—China. 3. Taoist art—China. 4. Buddhist art—China. I. Title. N8191.C6K37 2014 704.9'489951—dc23 2013036347 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction 1 Part 1: The Beginnings of Chinese Religious Art Chapter 1 Neolithic Period to Shang Dynasty 11 Chapter 2 Ceremonial -

The Many Guises of Xiaoluan: the Legacy of a Girl Poet in Late Imperial China

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Anne Gerritsen Article Title: The Many Guises of Xiaoluan: The Legacy of a Girl Poet in Late Imperial China Year of publication: 2005 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2005.0019 Publisher statement: This article was published as Gerritsen, A. (2005). The Many Guises of Xiaoluan: The Legacy of a Girl Poet in Late Imperial China. Journal of Women's History, 17, 2, pp. 38-61. No part of this article may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or distributed, in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photographic, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Indiana University Press The Many Guises of Xiaoluan: The Legacy of a Girl Poet in Late Imperial China Introduction In recent years the image of the talented woman writer has greatly enhanced our picture of premodern China. Thanks to the work of scholars like Ellen Widmer, Dorothy Ko, Susan Mann and Kang-i Sun Chang, to mention only a few, reference to a woman in China’s imperial past conjures up the image of a strong and sophisticated woman holding a book rather than a picture of the bound foot.1 No student of China’s late imperial period (roughly between 1500 and 1900) could justifiably claim unfamiliarity with the Chinese woman writer. -

Download (3MB)

Lipsey, Eleanor Laura (2018) Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32199 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts Eleanor Laura Lipsey Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2018 Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures China & Inner Asia Section SOAS, University of London 1 Abstract This is a study of the music culture of the Six Dynasties era (220–589 CE), as represented in certain texts of the period, to uncover clues to the music culture that can be found in textual references to music. This study diverges from most scholarship on Six Dynasties music culture in four major ways. The first concerns the type of text examined: since the standard histories have been extensively researched, I work with other types of literature. The second is the casual and indirect nature of the references to music that I analyze: particularly when the focus of research is on ideas, most scholarship is directed at formal essays that explicitly address questions about the nature of music. -

Poh Cheng Khoo Interrogating the Women Warrior

MIT4 Panel: "Asian Warrior Womanhood in Storytelling." Poh Cheng Khoo Interrogating the Women Warrior: War, Patriotism and Family Loyalty in Lady Warriors of the Yang Family (2001). The medieval Chinese are known to be heavily patriarchal, but even such a culture produced many formidable women warriors…Daughters of prominent military families trained in the martial arts. Wives of generals were often chosen for their battle skills. The Yang family of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) was one such military family. When the men were decimated on various military assignments, their wives, mothers, sisters and even maidservants took their places on the battlefield. (“Warriors: Asian women in Asian society”) “No group of women in Chinese history has commanded so much prestige and respect as the ladies of the Yang family. They are revered as great patriots who were willing to lay down their lives for the sake of their country” (Lu Yanguang, 100 Celebrated Chinese Women, 149). The genesis of this paper lies in a 40-part retelling of one of the more enduring woman warrior stories of historical China. When I saw this particular 2001 TV series which loosely translates into Lady Warriors of the Yang Family, I was working on my dissertation involving Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and hence the iconic figure of Fa Mu Lan. Contrary to Mulan’s concealment of gender in battle, here was a family of woman warriors from some ten centuries ago, none of whom had to compromise their true biological identity by cross-dressing or, according to Judith Lorber’s definition, turning “transvestite” (Richardson et al [eds.] 42). -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

Chikurin Shichiken 竹林七賢 Seven Wise Men of the Bamboo Thicket Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove

Notebook, Slide 31 Condensed Visual Classroom Guide to Daikokuten Iconography in Japan. Copyright Mark Schumacher. 2017. Chikurin Shichiken 竹林七賢 Seven Wise Men of the Bamboo Thicket Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove Below text from Japan Architecture and Art Net User System (JAANUS) Chn: Zhulinqixian. Lit. Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. A pictorial theme based on seven Chinese literati who, to escape the social chaos of the Wei-Jin period, fled to a secluded bamboo grove chikurin 竹林 where they could express their personalities freely by the enjoyment of pure conversation seidan 清談, music, and wine. The Seven Sages are: Ruan Ji (Jp: Gen Seki 阮籍; 210-263), Ji Kang (Jp: Kei Kou 稽康; 223-266), Shan Tao (Jp: San Tou 山 涛; 205-266), Xiang Xiu (Jp: Kyou Shuu 向秀; 221-300), Liu Ling (Jp: Ryou Rei 劉伶; ca. 225- 280), Wang Rong (Jp: Oujuu 王戎; 234-305), and, Ruan Xian (Jp: Gen Kan 阮咸, nephew of Ruan Ji). All were famous for the purity of their reclusive spirits, their strong Taoist and anti- Confucian values, and their strikingly eccentric personalities. The Seven Sages are mentioned in several Chinese texts, most notably Shushuoxinyu (Jp: SESETSU SHINGO 世説新語; ca 5c) or New Specimens of Contemporary Talk. The earliest depiction of the subject is found on a set of late 4c or early 5c clay tomb tiles from the Xishanqiao 西善橋 area of Nanjing 南京. Typical Chinese iconography shows gentlemen playing musical instruments and writing poetry as well as drinking wine. The subject was popular with Japanese painters of the Momoyama and early Edo periods who tended to transform the theme into a rather generalized image of reclusive scholars engaging in literary pursuits. -

Gender and the Poetry of Chen Yinke

Nostalgia and Resistance: Gender and the Poetry of Chen Yinke Wai-yee Li 李惠儀 Harvard University On June 2, 1927, the great scholar and poet Wang Guowei 王國維 (1877- 1927) drowned himself at Lake Kunming in the Imperial Summer Palace in Beijing. There was widespread perception at the time that Wang had committed suicide as a martyr for the fallen Qing dynasty, whose young deposed emperor had been Wang’s student. However, Chen Yinke 陳寅恪 (1890-1969), Wang’s friend and colleague at the Qinghua Research Institute of National Learning, offered a different interpretation in the preface to his “Elegy on Wang Guowei” 王觀堂先生輓詞并序: For today’s China is facing calamities and crises without precedents in its several thousand years of history. With these calamities and crises reaching ever more dire extremes, how can those whose very being represents a condensation and realization of the spirit of Chinese culture fail to identify with its fate and perish along with it? This was why Wang Guowei could not but die.1 Two years later, Chen elaborated upon the meaning of Wang’s death in a memorial stele: He died to make manifest his will to independence and freedom. This was neither about personal indebtedness and grudges, nor about the rise or fall of one ruling house… His writings may sink into oblivion; his teachings may yet be debated. But this spirit of independence and freedom of thought…will last for eternity with heaven and earth.2 Between these assertions from 1927 and 1929 is a rhetorical elision of potentially different positions. -

The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: “My

THE DIARY OF A MANCHU SOLDIER IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA The Manchu conquest of China inaugurated one of the most successful and long-living dynasties in Chinese history: the Qing (1644–1911). The wars fought by the Manchus to invade China and consolidate the power of the Qing imperial house spanned over many decades through most of the seventeenth century. This book provides the first Western translation of the diary of Dzengmeo, a young Manchu officer, and recounts the events of the War of the Three Feudatories (1673–1682), fought mostly in southwestern China and widely regarded as the most serious internal military challenge faced by the Manchus before the Taiping rebellion (1851–1864). The author’s participation in the campaign provides the close-up, emotional perspective on what it meant to be in combat, while also providing a rare window into the overall organization of the Qing army, and new data in key areas of military history such as combat, armament, logistics, rank relations, and military culture. The diary represents a fine and rare example of Manchu personal writing, and shows how critical the development of Manchu studies can be for our knowledge of China’s early modern history. Nicola Di Cosmo joined the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Historical Studies, in 2003 as the Luce Foundation Professor in East Asian Studies. He is the author of Ancient China and Its Enemies (Cambridge University Press, 2002) and his research interests are in Mongol and Manchu studies and Sino-Inner Asian relations. ROUTLEDGE STUDIES