Cycling Beyond Your Sixties: the Role of Cycling in Later Life and How It Can Be Supported and Promoted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Empirical Study of Bicyclists' Turning Behaviour at Signalized Intersections

An Empirical Study of Bicyclists' Turning Behaviour at Signalized Intersections by Adam James Fraser A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in the fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Applied Science in Civil Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2018 ©Adam James Fraser Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is the true copy of the thesis including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that this thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Efforts to increase cycling mode share have seen some success in North America, though challenges persist due to real and perceived safety issues. Of particular concern are left turns at signalized intersections. Left turns can be particularly challenging to traverse and often leave cyclists feeling unsafe, especially those who are less experienced. To reduce conflict and enhance safe left-turn maneuvering, the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania has initiated a pilot study for the installation of two-phase left turn bike boxes. This thesis investigates how the installation of two-phase left turn bike boxes influence left-turning behaviour at signalized intersections. A literature review found few studies that demonstrate the benefits of two-phase left turn bike boxes, and generally few studies that document left turn behaviour in a North American context. Similarly, few studies differentiate between signal control infractions and road space infractions. The approach used a before and after video analysis of five unique left-turning scenarios of installation of two-phase left turn bike boxes. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Master Plan Study

FINAL REPORT PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE MASTER PLAN STUDY Prepared by: In association with: I N E S T E R N A T Marshall I O Macklin N A Monaghan L PROJECT MANAGERS • ENGINEERS • SURVEYORS • PLANNERS January 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page Chapter Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................1-1 3.2 Study Purpose ................................. 3-3 1.1 About Vaughan................................1-1 3.3 The Master Plan Strategy................ 3-3 1.2 Why Does Vaughan Need a Pedestrian and Bicycle Master 4.0 NETWORK ............................4-1 Plan?..................................................1-2 4.1 Creating a Pedestrian and Cycling 1.3 Vision for Walking and Cycling Network .......................................... 4-1 in the City of Vaughan......................1-3 4.2 Network Goals and Objectives ....... 4-1 2.0 CONTEXT................................2-1 4.3 Objective 4a: Determining a 2.1 Benefits to Walking and Cycling ....2-1 Clearly Defined Network Structure.......................................... 4-1 2.1.1 Transportation Benefits.................2-1 2.1.2 Recreation, Health and Fitness 4.4 Objective 4b: Provide Designated Benefits .........................................2-1 On and Off-Road Pedestrian and 2.1.3 Environmental Benefits.................2-2 Cycling Facilities ............................ 4-3 2.1.4 Economic Benefits........................2-2 4.4.1 Class 1 Facilities: Multi-Use 2.2 Previous City Initiatives ..................2-2 Pathways........................................ 4-3 4.4.2 Class 2 Facilities: Bike Lanes / 2.3 Master Plan Initiatives.....................2-3 Paved Shoulders ............................ 4-5 4.4.3 Class 3 Facilities: Signed-Only 2.3.1 User Survey...................................2-3 Routes............................................ 4-6 2.3.2 Intercept User Surveys ..................2-3 4.4.4 Class 4 Facilities: Footpaths / 2.3.3 General Findings ...........................2-4 Hiking Trails................................. -

Normalising Cycling Mobilities

APPLIED MOBILITIES https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2021.1872206 ARTICLE Normalising cycling mobilities: an age-friendly approach to cycling in the Netherlands Wilbert den Hoed a and Helen Jarvisb aEuropean Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK; bSchool of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Cycling is promoted as a form of urban travel with well-established Received 15 January 2019 benefits to health, liveability and wellbeing. These benefits are Accepted 4 January 2021 comparatively large for older people, a growing segment in many KEYWORDS populations. Yet, support for the normalisation of cycling mobilities Cycling; mobility; ageing; for all ages varies considerably. It is usual to contrast low-cycling active ageing; normalisation; contexts, such as the UK, with high-cycling areas, typically favouring mobile methods highest-rate paradigmatic urban centres. To challenge a too sim plistic imitation and re-creation of engineering solutions elsewhere, we draw attention to diverse cycling habits and norms in residents of a more ordinary high-cycling area (suburban Rotterdam), and observe how cycling is normalised throughout the lifecourse. Using mobile and biographical methods, we argue that a more nuanced appreciation of cycling normalisation is gained from viewing age ing and cycling relationally and biographically. This is because the habit-forming realm of normalisation functions through both con scious decisions and unconscious practice, bound up with life events and the external environment. The findings suggest that age-friendly city strategies and urban mobility policies should more closely consider locally constituted social and cultural processes, beyond providing infrastructure. -

Where Everyday Mobility Meets Tourism: an Age-Friendly Perspective on Cycling in the Netherlands and the UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Strathclyde Institutional Repository JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1656727 Where everyday mobility meets tourism: an age-friendly perspective on cycling in the Netherlands and the UK Wilbert den Hoed European Policies Research Centre, School of Government and Public Policy, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Tourism is traditionally presented as an escape from daily life and Received 31 May 2018 located at places we do not normally visit. Against a backdrop of prob- Revised 5 July 2019 lematic pressures on (urban) tourist centres and mobility systems, some Accepted 12 August 2019 scholars have explored the possibility of tourism nearer the home. Such KEYWORDS locations, however, are often perceived too mundane or are not suffi- Tourism; active mobility; ciently equipped as tourist destinations. In addition, the study of tourist cycling; well-being; ageing experiences is often dominated by motorised transport, and with limited consideration of older age groups. This article combines different strands of literature to consider the role of active mobility among older people and its contribution to age-friendliness and more proximate forms of tourism. Two case studies in the contrasting mobility contexts of the Netherlands and the United Kingdom show how everyday mobili- ties contain implicit and explicit tourism elements. Commutes, local vis- its, and active travel itself may act as springboards for tourism close(r) to home. Using biographical and mobile methods, this article shows how local tourism roots in individual lifecourses, is shaped by the trans- port environment, and supports social and physical well-being. -

Shared Speed for Safe Transportation and Sustainable Cities

Shared speed for safe transportation and sustainable cities A study from a cyclist perspective on how traffic design can promote shared speed and the acceptance of mixed traffic Master’s thesis in Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering PONTUS JÖRGENSEN DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND CIVIL ENGINEERING CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2020 www.chalmers.se DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND CIVIL ENGINEERING Division of Geology and Geotechnics, Research Group Urban Mobility Systems CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2020 www.chalmers.se Master’s Thesis ACEX30 Shared speed for safe transportation and sustainable cities A study from a cyclist perspective on how traffic design can promote shared speed and the acceptance of mixed traffic PONTUS JÖRGENSEN Shared speed for safe transportation and sustainable cities A study from a cyclist perspective on how traffic design can promote shared speed and the acceptance of mixed traffic Master’s Thesis in the Master’s Programme Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering PONTUS JÖRGENSEN © PONTUS JÖRGENSEN, 2020. Supervisor: Charlotte Berglund, Roger Johansson, Sweco Examiner: Xiaobo Qu, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Examensarbete ACEX30 Institutionen för arkitektur och samhällsbyggnadsteknik Chalmers tekniska högskola, 2020 Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Geology and Geotechnics Research Group Urban Mobility Systems Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Sweden Telephone: +46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: Shared -

How Infrastructures Can Promote Cycling in Mediterranean Cities

Title: How infrastructures can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Sevilla. Keywords: Bicycling. Cycling infrastructure. Active mobility. Sustainable transport. Sevilla (Seville). Spain. Europe. Corresponding Author: Dr. Ricardo Marques, Full Professor Corresponding Author's Institution: Universidad de Sevilla Corresponding Author's postal address and contact: Sistema Integral de la Bicicleta de la Universidad de Sevilla (SIBUS) Vicerrectorado de Infraestructuras, Universidad de Sevilla Pabellón de Brasil, Paseo de las Delicias s/n 41012 Sevilla – Spain Phone: (34)954550961, Cell phone: (34)665534446 E-mail: [email protected] First Author: Ricardo Marques, Full Professor Authors: Ricardo Marques. Full Professor. SIBUS - University of Sevilla. Spain. E-mail: [email protected] Vicente Hernandez-Herrador. Student. SIBUS - University of Sevilla. Spain E-mail: [email protected] Manuel Calvo-Salazar. Mobility consultant. Sevilla. Spain. E-mail: [email protected] Jose-Antonio García-Cebrián. Urban manager. E-mail: [email protected] Order of authors: Marqués, R., Hernández-Herrador, V., Calvo-Salazar, M., and García-Cebrián, J. A. ABSTRACT In this paper we analyze the development of a separated cycling infrastructure in Sevilla during the period 2006 – 2011, as well as its consequences for the city mobility. The development in such a short period of time of a fully segregated network of cycle paths has proven to be a valuable tool for the promotion of bicycle mobility in a city without previous tradition of utilitarian cycling. Besides segregation from motorized traffic, connectivity, continuity, visibility, uniformity, bi- directionality and comfort have proven to be good criteria for the design of such infrastructure. All these criteria are aimed to make cycling not just safe, but also easy and comfortable for everybody. -

Abstracting Mobility Flows from Bike-Sharing Systems

Senseable City Lab :.:: Massachusetts Institute of Technology This paper might be a pre-copy-editing or a post-print author-produced .pdf of an article accepted for publication. For the definitive publisher-authenticated version, please refer directly to publishing house’s archive system SENSEABLE CITY LAB Public Transport https://doi.org/10.1007/s12469-020-00259-5(0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL RESEARCH Abstracting mobility flows from bike-sharing systems 1,2 1 1 Fabio Kon • E´derson Ca´ssio Ferreira • Higor Amario de Souza • 2,3 2,4 2 Fa´bio Duarte • Paolo Santi • Carlo Ratti Accepted: 9 November 2020 Ó Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2021 Abstract Bicycling has grown significantly in the past ten years. In some regions, the implementation of large-scale bike-sharing systems and improved cycling infra- structure are two of the factors enabling this growth. An increase in non-motorized modes of transportation makes our cities more human, decreases pollution, traffic, and improves quality of life. In many cities around the world, urban planners and policymakers are looking at cycling as a sustainable way of improving urban mobility. Although bike-sharing systems generate abundant data about their users’ travel habits, most cities still rely on traditional tools and methods for planning and policy-making. Recent technological advances enable the collection and analysis of large amounts of data about urban mobility, which can serve as a solid basis for evidence-based policy-making. In this paper, we introduce a novel analytical method that can be used to process millions of bike-sharing trips and analyze bike- sharing mobility, abstracting relevant mobility flows across specific urban areas. -

Approaching Bike Hazards Via Crowdsourcing of Volunteered Geographic Information

sustainability Article Approaching Bike Hazards via Crowdsourcing of Volunteered Geographic Information Rafael Hologa *,† and Nils Riach † Physical Geography, University of Freiburg, Schreiberstraße 20, 79085 Freiburg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 25 August 2020; Published: 28 August 2020 Abstract: Information on individual hazard perception while cycling and the associated feeling of safety are key aspects to foster sustainable urban cycling mobility. Although cyclist’s perceptions must also be critically reviewed, such crowdsourced Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) provides wide-ranging insights on diverse hazard categories in cycling. In this case study in the city of Freiburg, Germany, hazard perceptions, information about lane types, and the underlying routes were crowdsourced via an open source smartphone application by a small group with the aim of providing cyclists with effective solutions. By dealing with levels of reliability, we show that even a small group of laypersons can generate an extensive and valuable set of VGI consisting of comprehensive hazard categories. We demonstrate that (1) certain hazards are interlinked to specific lane types, and (2) the individual hazard perceptions and objective parameters, i.e., accident data, are often congruent spatially; consequently, (3) dangerous hot spots can be derived. By considering cyclists’ needs, this approach outlines how a people-based perspective can supplement regional planning on the local scale. Keywords: crowdsourcing; Volunteered Geographic Information; safety; hazards; cycling; perception; GIScience; regional planning 1. Introduction In their daily routines, cyclists are often confronted with dangerous situations while commuting in an urban context. -

Bikeability and Emerging Phenomena in Cycling: Exploratory Analysis and Review

sustainability Review Bikeability and Emerging Phenomena in Cycling: Exploratory Analysis and Review Ugo N. Castañon * and Paulo J. G. Ribeiro * Centre of Territory Environment and Construction (CTAC), University of Minho, 4800-058 Guimarães, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (U.N.C.); [email protected] (P.J.G.R.) Abstract: Recent strategies to improve the performance of the cycling mode of transport are based on infrastructural, behavioral, and multimodal measures, which are related to the concept of bikeability. A literature review on “bikeability indexes” was conducted focusing on indicators, using a four-step systematic process. Fourteen studies were included for the final analysis and provided 138 indicators, 17 criteria, and four domains. The exploratory analysis evidenced limited application of indicators related to pollution, scarce use of indicators related to bicycle sharing systems (BSS), absence of indicators related to electric bicycles, lack of indicators related to digital solutions, and the need of a calibration and validation process for bikeability indexes. Considering the changes and opportunities created by emerging innovations (namely BSS and electric bicycles) and the health trade-off related to pollution reduction, this research reveals that the current bikeability indexes do not fully address the real potential of a cycle network, limiting its use as a comprehensive tool for the promotion of sustainable mobility. Keywords: systematic review; bikeability index; bicycle sharing systems; electric bicycles; sustain- able mobility Citation: Castañon, U.N.; Ribeiro, P.J.G. Bikeability and Emerging Phenomena in Cycling: Exploratory 1. Introduction Analysis and Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2394. https://doi.org/ Bikeability is a broad concept that relates different factors to bicycle use, depending 10.3390/su13042394 on the focus and interest of the research. -

Promotion and Development of Non-Motorized Transport in Baku

JUNE 2019 WORLD BANK GROUP Development of non-motorized transportation in Baku City ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The report was prepared by a World Bank team led by Nijat Valiyev (Senior Infrastructure Specialist) and Henrik Grell (Consultant, COWI). The report benefited from the comments of Aymen Ali (Senior Transport Specialist), Antonio Nunez (Senior Transport Specialist), Ross Pavis (Senior Operations Officer), and Hatem Chahbani (Senior Transport Specialist). The team is grateful for the guidance provided by Karla Gonzalez Carvajal (Practice Manager) and Naveed Naqvi (Country Manager). The World Bank team would like to thank its counterparts in Azerbaijan including Baku Transport Agency, State Committee for City Planning and Architecture, and others for fruitful discussions, consultations, ideas and access to data and information. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This report, created by the World Bank, is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CCBY3.0) license. DEVELOPMENT OF NON-MOTORIZED TRANSPORTATION IN BAKU CITY 3 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ....................................................................... 7 PUBLIC PERCEPTION AND DEMAND FOR NMT ............................................. 9 NMT POLICY OBJECTIVES FOR BAKU -

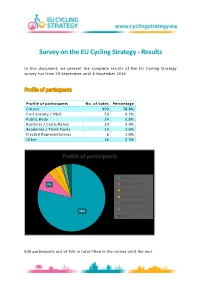

Survey on the EU Cycling Strategy - Results

Survey on the EU Cycling Strategy - Results In this document, we present the complete results of the EU Cycling Strategy survey run from 29 September until 6 November 2016. Profile of participants Profile of participants No. of votes Percentage Citizen 499 78.8% Civil Society / NGO 59 9.3% Public Body 24 3.8% Business / Consultancy 19 3.0% Academia / Think Tanks 10 1.6% Elected Representatives 6 1.0% Other 16 2.5% Profile of participants Citizen 9% Civil society / NGO Public body Business / Consultancy Elected representatives Academia / Think tanks 79% Other 630 participants out of 635 in total filled in the survey until the end. Survey on the EU Cycling Strategy - Results If applicable, organisation active on: 9% Local level 10% National level 41% 13% Regional level European level 27% International/global level 10 most represented countries 40.26% 8.47% 5.59% 4.79% 3.99% 3.51% 3.51% 3.35% 3.04% 2.88% Netherlands Germany Belgium United Kingdom Austria France Ireland Finland Malta Spain The participants come from in total 37 countries including 8 non -European countries such as Canada, Colombia or Vietnam. 2 Survey on the EU Cycling Strategy - Results List of proposed policy actions 1. The EU should prioritize active modes (walking and cycling) over individual motorized transport. 2. The EU should set a target of doubling cycling across the EU over the next 10 years. 3. Every relevant infrastructure project should take cycling into consideration as much as possible. 4. Minimum EU cycling infrastructure quality criteria should be established for relevant projects co-funded with EU money. -

Cycling Plans, Strategies and Design Guidelines Contact Armin Wagner Transport Policy Advisor GIZ Transport and Mobility [email protected]

Cycling Plans, Strategies and Design Guidelines Contact Armin Wagner Transport Policy Advisor GIZ Transport and Mobility [email protected] Compiled by Adriana Lopez Hernadez JanuaryPage 2014 1 Content 1. Europe 2. America 3. Asia 4. Australia and Oceania region 5. Africa Page 2 Austria 1. Europe Czech Republic Denmark Finland France Germany Ireland Netherlands Norway Portugal Slovak Republic Spain Sweden Picture: Manfred Breithaupt Switzerland United Kingdom Page 3 Austria Cycling Master Plan. Strategy to promote cycling in Austria (Masterplan Radfahren Strategie zur Förderung des Radverkehrs in Österreich – Only available in German) The master plan includes milestone programs such as "Shutdown on Cycling" and the enterprise competition "Bike to Business “ to promote more environmentally friendly and healthy mobility in everyday life. Mobility ought to be efficient and environmentally friendly, but it should also be healthy and safe. Fields of action: *enhanced cooperation / coordination of the cycling competent Actors, *attractive and safe cycling infrastructure, *bicycling friendly and safe transport organization *Mobility management, *Optimize the intermodal network, Published in 2006 *Awareness and traffic education, *biking and generally friendly framework conditions http://www.komobile.at/download/ka_masterplan_radfahren.pdf Page 4 Czech Republic National Cycling Development Strategy of the Czech Republic The Cycling Strategy aims at creating the conditions to transform the “popular unregulated” cycling towards a “cultivated and systematically supported cycling”. The entire process of planning of the Czech Cycling Strategy and the resulted strategic plan emerge several important conclusions: In the Czech Republic, there exist resources, which could be used in a well organized way, to support the cycle transport nation-wide.