The Northern Negev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

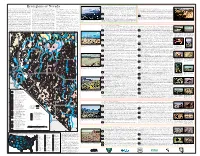

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Synoptic-Scale Control Over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates

JUNE 2018 ARMONETAL. 1077 Synoptic-Scale Control over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates MOSHE ARMON Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel ELAD DENTE Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, and Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel JAMES A. SMITH Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey YEHOUDA ENZEL AND EFRAT MORIN Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel (Manuscript received 23 January 2018, in final form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT Rainfall in the Levant drylands is scarce but can potentially generate high-magnitude flash floods. Rainstorms are caused by distinct synoptic-scale circulation patterns: Mediterranean cyclone (MC), active Red Sea trough (ARST), and subtropical jet stream (STJ) disturbances, also termed tropical plumes (TPs). The unique spatiotemporal char- acteristics of rainstorms and floods for each circulation pattern were identified. Meteorological reanalyses, quantitative precipitation estimates from weather radars, hydrological data, and indicators of geomorphic changes from remote sensing imagery were used to characterize the chain of hydrometeorological processes leading to distinct flood patterns in the region. Significant differences in the hydrometeorology of these three flood-producing synoptic systems were identified: MC storms draw moisture from the Mediterranean and generate moderate rainfall in the northern part of the region. ARST and TP storms transfer large amounts of moisture from the south, which is converted to rainfall in the hyperarid southernmost parts of the Levant. -

Polio October 2014

Europe’s journal on infectious disease epidemiology, prevention and control Special edition: Polio October 2014 Featuring • The polio eradication end game: what it means for Europe • Molecular epidemiology of silent introduction and sustained transmission of wild poliovirus type 1, Israel, 2013 • The 2010 outbreak of poliomyelitis in Tajikistan: epidemiology and lessons learnt www.eurosurveillance.org Editorial team Editorial advisors Based at the European Centre for Albania: Alban Ylli, Tirana Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Austria: Reinhild Strauss, Vienna 171 83 Stockholm, Sweden Belgium: Koen De Schrijver, Antwerp Telephone number Belgium: Sophie Quoilin, Brussels +46 (0)8 58 60 11 38 Bosnia and Herzogovina: Nina Rodić Vukmir, Banja Luka E-mail Bulgaria: Mira Kojouharova, Sofia [email protected] Croatia: Sanja Musić Milanović, Zagreb Cyprus: to be nominated Editor-in-chief Czech Republic: Bohumir Križ, Prague Ines Steffens Denmark: Peter Henrik Andersen, Copenhagen Senior editor Estonia: Kuulo Kutsar, Tallinn Kathrin Hagmaier Finland: Outi Lyytikäinen, Helsinki France: Judith Benrekassa, Paris Scientific editors Germany: Jamela Seedat, Berlin Karen Wilson Greece: Rengina Vorou, Athens Williamina Wilson Hungary: Ágnes Csohán, Budapest Assistant editors Iceland: Haraldur Briem, Reykjavik Alina Buzdugan Ireland: Lelia Thornton, Dublin Ingela Söderlund Italy: Paola De Castro, Rome Associate editors Kosovo under UN Security Council Resolution 1244: Lul Raka, Pristina Andrea Ammon, Stockholm, Sweden Latvia: Jurijs Perevoščikovs, -

Making the Desert Bloom Facilitators Guide

Jewish National Fund Tu BiShvat in the Schools, 2020/5780 Making the Desert Bloom Facilitators Guide Intro to Jewish Long before there was Earth Day there was Tu BiShvat, the Jewish New Year for Trees, which falls on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shvat. Tu BiShvat marks the time National Fund when trees emerge from their winter sleep and begin a new cycle. It is a celebration and Tu BiShvat of spring’s rebirth and renewal, an appreciation of the interconnectedness of man and nature, and the marker by which a tree’s age is determined. Tu BiShvat has its roots in the Bible: “On the third day of creation, God created ‘seed- bearing plants, fruit trees after their kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it’” (Genesis 1:11). God then put Adam in the garden to “till it and tend it” (2:15), making humans stewards of the earth. Tu BiShvat was the date used by farmers to calculate the year’s crop yield and determine the tithe that the Bible requires. It also marks the beginning and end of the first four years of a tree’s growth, during which it is forbidden to eat its fruit. As the Jewish Arbor Day, Tu BiShvat embodies the strong dedication to ecology, environmentalism, and conservation that Jewish National Fund has championed since its inception in 1901. Since the time of the Kabbalah, Sephardi Jews, originally from Spain, held a special Tu BiShvat Seder at which they ate 30 kinds of fruit from Israel: 10 whose outsides and insides were both eaten (like grapes), 10 whose outsides were eaten but whose insides were thrown away (like carobs), and 10 whose insides were eaten but whose outsides were thrown away (like almonds). -

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave http://www.desertusa.com/desert.html In most modern classifications, the deserts of the United States and northern Mexico are grouped into four distinct categories. These distinctions are made on the basis of floristic composition and distribution -- the species of plants growing in a particular desert region. Plant communities, in turn, are determined by the geologic history of a region, the soil and mineral conditions, the elevation and the patterns of precipitation. Three of these deserts -- the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran and the Mojave -- are called "hot deserts," because of their high temperatures during the long summer and because the evolutionary affinities of their plant life are largely with the subtropical plant communities to the south. The Great Basin Desert is called a "cold desert" because it is generally cooler and its dominant plant life is not subtropical in origin. Chihuahuan Desert: A small area of southeastern New Mexico and extreme western Texas, extending south into a vast area of Mexico. Great Basin Desert: The northern three-quarters of Nevada, western and southern Utah, to the southern third of Idaho and the southeastern corner of Oregon. According to some, it also includes small portions of western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Bordered on the south by the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Mojave Desert: A portion of southern Nevada, extreme southwestern Utah and of eastern California, north of the Sonoran Desert. Sonoran Desert: A relatively small region of extreme south-central California and most of the southern half of Arizona, east to almost the New Mexico line. -

'The Volunteer Tent'

September 2012 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES: 2011-12 AT ‘THE TENT’ – OUR ARAB-JEWISH BEDOUIN VOLUNTEER CENTER Celebrating a decade of social action and active citizenship, the ‘Volunteer Tent’ is NISPED-AJEEC’s flagship youth and young people’s community involvement program. In 2002, a small group of community activists from AJEEC pitched a tent of hope and change, founding the Arab-Bedouin Volunteer Center (The Volunteer Tent). Today, the Tent is a hub of volunteerism, community work and Arab-Jewish cooperation engaging some 700 volunteers and benefitting 10,000 people in the recognized and unrecognized Arab Bedouin villages of the Negev. The ‘Tent’ recruits volunteers from within the Arab-Bedouin community, provides them with professional training and ongoing supervision, identifies community needs and deploys volunteers throughout the Bedouin towns and villages of the Negev in a variety of programs designed to meet these needs. The primary focus of the ‘Tent” programs is on children and youth at risk. 1 In 2011-12, 700 volunteers: Arab Bedouin university and college students, high-school students; Jewish high school graduates from the Scouts youth movement and Arab Bedouin high school graduates, among them 67 full-time gap-year volunteers conducted a wide range of educational and social enrichment programs in which some 7,000 children and youth participated on a regular basis at least once a week throughout the year. Several thousand others – both children and adults- benefited from a variety of special community–based projects and activities organized by the volunteers in the Bedouin towns and villages of the Negev. An important factor contributing to the success of our volunteer programs are the strategic partnerships forged over the years and significantly expanded this year. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Terroir and Territory on the Colonial Frontier: Making New-Old World Wine in the Holy Land1

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2020;62(2):222–261. 0010-4175/20 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0010417520000043 Terroir and Territory on the Colonial Frontier: Making New-Old World Wine in the Holy Land1 DANIEL MONTERESCU Sociology and Social Anthropology, Central European University ARIEL HANDEL Minerva Humanities Center, Tel Aviv University It is hard to believe, but emerging regions that have had little impact on the wine world are forcing consumers to pay attention to a completely different part of the world. Awine epicenter that includes countries like Greece, Israel and Lebanon might look familiar to someone a couple of thousand years old, but it is certainly a new part of the wine world for the rest of us. ———Squires, Wine Advocate, 2008 1 Wine professionals quoted in this article have given their written consent to reveal their real names after receiving the transcriptions of respective interviews and conversations. The project was reviewed by the CEU ethical research committee and received final institutional endorsement in November 2014. Acknowledgements: This article has been fermenting and maturing for almost a decade. Following initial fieldwork in 2011 it was first presented at the conference “Mediterranean Criss-crossed and Constructed” at Harvard University. With age, it was presented in numerous venues in Israel/ Palestine, Europe, and North America. -

The Impact of Sanitation on Child Health in Vulnerable Populations: a Multicountry Analysis Across Income Levels

The Impact of Sanitation on Child Health in Vulnerable Populations: a Multicountry Analysis across Income Levels by Jesse Doyle Contreras A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph N.S. Eisenberg, Chair Associate Professor Veronica Berrocal, University of California, Irvine Associate Professor Rafael Meza Assistant Professor Jon Zelner Jesse D. Contreras [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9766-2945 © Jesse D. Contreras 2020 For my brother, Gabriel Contreras, who ensured that I could be here today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Joe Eisenberg, for your support throughout my master’s and doctoral education. I came to Michigan barely knowing what a Ph.D. was, but your guidance helped me navigate many new worlds without ever feeling lost. Over six years, you have repeatedly helped me find the meaningful story behind my own words, as well as the best local restaurants across three countries, and I am a much better researcher thanks to you. I would like to thank Dr. Rafael Meza for your kindness and for bestowing me with countless lessons, epidemiological and otherwise. Thank you to Dr. Jon Zelner and Dr. Veronica Berrocal for helping me to expand my understanding of statistical methods, which I could not have done without you, and for making this a much better dissertation in the process. I would like to thank the individuals who allowed this research to happen, including all of my co-authors, the Department of Epidemiology administrative team, and the master’s interns who gave key support from the field: Maxwell Salvatore, Grace Christensen, Moira Dickinson, Ruth Thomas, and Marie Kaniecki. -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

The Negev Bedouin Within the Legal and Spatial Conflict with the State of Israel

Fighting for the Community, Tradition, and Culture - The Negev Bedouin within the Legal and Spatial Conflict with the State of Israel Magdalena Lacka Supervisor: Dr. Polly Pallister-Wilkins Student number: 10394362 Second reader: Dr. Martijn Dekker Master: Conflict Resolution and Governance Graduate School of Social Sciences University of Amsterdam Word count: 17499 June 2017 Abstract This thesis will study the Israeli land policies with respect to the Negev Bedouin. The purpose of this study is to investigate how the Israeli land laws and spatial planning policies impact the Negev Bedouin’s ability to access their human and land rights. The empirical part of this study was conducted in May 2017. Data for this research was collected through the methodological triangulation of document analysis and semi-structured qualitative interviews with experts and NGOs’ representatives working with the Negev Bedouin. A theoretical framework based on settler colonialism theory and critical legal geography theory, was used. Another objective of this study was to focus on the issue of indigeneity with respect to the Negev Bedouin, as this issue seemed to be an essential factor in the Bedouin land dispute. The whole conflict between the the Negev Bedouin and the State of Israel will be further illustrated in the case study of the village of Umm al-Hiran, in order to better exemplify the issues at stake. On the basis of the results of this research, it can be concluded that the Israeli modifications to the Ottoman and British land laws have served as a basis for the Negev Bedouin land dispossession, while the other Israeli land laws provided the means to limit the allocation of land to the Bedouin and to pressure the Bedouin population in the Negev.