A Vision for Scholar-Activists of Color John Streamas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July Trivia Questions and Answers

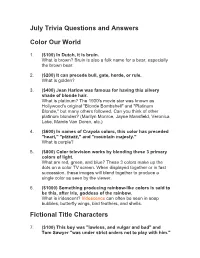

July Trivia Questions and Answers Color Our World 1. ($100) In Dutch, it is bruin. What is brown? Bruin is also a folk name for a bear, especially the brown bear. 2. ($200) It can precede bull, gate, horde, or rule. What is golden? 3. ($400) Jean Harlow was famous for having this silvery shade of blonde hair. What is platinum? The 1930's movie star was known as Hollywood's original "Blonde Bombshell" and "Platinum Blonde," but many others followed. Can you think of other platinum blondes? (Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, Veronica Lake, Mamie Van Doren, etc.) 4. ($600) In names of Crayola colors, this color has preceded "heart," "pizzazz," and "mountain majesty." What is purple? 5. ($800) Color television works by blending these 3 primary colors of light. What are red, green, and blue? These 3 colors make up the dots on a color TV screen. When displayed together or in fast succession, these images will blend together to produce a single color as seen by the viewer. 6. ($1000) Something producing rainbow-like colors is said to be this, after Iris, goddess of the rainbow. What is iridescent? Iridescence can often be seen in soap bubbles, butterfly wings, bird feathers, and shells. Fictional Title Characters 7. ($100) This boy was "lawless, and vulgar and bad" and Tom Sawyer "was under strict orders not to play with him." Who is Huckleberry Finn? Huck Finn narrates Adventures of Huck Finn, the sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, published in 1884. 8. ($200) This detective was modeled in part on Dr. -

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 13 Tossups 1. a New Book in The

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 13 Tossups 1. A new book in the series describes her adventures in Rome with felines, her first new adventure in almost 50 years. She already had an adventure with a cat that her neighbor Pepito was set to torture among a pack of dogs, leading her to confirm that he was indeed, a "bad hat." She made amends with Pepito and later traveled to London to visit him, and stowed away with him in a gypsy caravan, much to the chagrin of Miss Clavel. The creation of Ludwig Bemelman, for ten points, name this red-haired spitfire who is not afraid of mice, and walks through Paris with her eleven nameless companions each day at half-past nine. Answer: Madeline 2. The last verse of this song reflects suspicions about the influence of aliens on the Bible and references the book of Ezekiel. Featured in the film The Virgin Suicides, Dennis DeYoung ends most of his concert performances with it. Reaching number 8 on the Billboard charts and coming from The Grand Illusion album but perhaps better known for being a favorite of Eric Cartman on South Park, name, for ten points, this Styx song concerning "a gathering of angels" singing a song of hope and setting "an open course for the virgin sea." Answer: "Come Sail Away" 3. Both Fritz Lang's Journey to the Lost City and Jean Renoir's The River were filmed in this country, which was also the setting of Powell and Pressburger's Black Narcissus. Marguerite Duras made a 1975 movie about its "Song," and Louis Malle directed a 378-minute epic documentary that called it a "Phantom." Also featured heavily in the James Bond film Octopussy and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, this is, for ten points, what nation that inspired a Walt Whitman poem, an E.M. -

Desperate Domesticity: the American 1950S ENG 4953 (T 6-8 in CBD 0224) 3/8/16

Professor M. Bryant Spring 2016 Desperate Domesticity: The American 1950s ENG 4953 (T 6-8 in CBD 0224) 3/8/16 Office: 4360 Turlington Hall Office Hours: T period 4, R period 9 & by appointment E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://people.clas.ufl.edu/mbryant/ This course explores fraught constructions of domesticity in American literary and popular culture of the 1950s, focusing on the nuclear family, gender roles (especially Housewife and Organization Man), the rise of suburbia, and alternative domesticities. Our writers will include John Cheever, Gwendolyn Brooks, Patricia Highsmith, Flannery O’Connor, Tennessee Williams, Sloan Wilson, Robert Lowell, and Sylvia Plath. Our postwar magazine readings come Ebony, Ladies’ Home Journal, The New Yorker, and One. We’ll explore the family sitcoms The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, as well as the teen delinquent films Rebel Without a Cause and Blackboard Jungle. We end with retrospective images of the American 1950s in contemporary culture. In addition to writing a short paper and a seminar paper, you’ll give a presentation that addresses key components of an assigned text. You’ll also submit a Florida Fifties archive worksheet and design a Faux Fifties ad. TEXTS Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (also available as UF e-book) John Cheever The Stories of John Cheever Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt Gwendolyn Brooks, Selected Poems Flannery O’Connor, The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor Tennessee Williams, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Sloan Wilson, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit Robert Lowell, Life Studies/For the Union Dead Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar (HarperPerennial) Fifties family sitcoms Popular magazines on Microfilm (Library Reserve), or try finding them on EBay Critical essays on UF Libraries course reserves (Ares) POLICIES 1. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

Classic Tv and Faith: Vii - Leave It to Beaver ‘Red and Yellow, Black and White

“CLASSIC TV AND FAITH: VII - LEAVE IT TO BEAVER ‘RED AND YELLOW, BLACK AND WHITE . .’” Karen F. Bunnell Elkton United Methodist Church August 19, 2012 Galatians 3:23-29 Luke 19:1-10 Life has been different this week without the Olympics on television. I don’t know about you, but I was glued to the TV for two weeks, watching the action. I don’t want to tell you how many nights I stayed up until midnight watching the competition, and then when my alarm went off at 5:30 a.m., turned it back on again. It was so great to watch how well everyone did. Who will ever forget watching Michael Phelps achieve something no other Olympic athlete has ever done? Or who will forget watching Usain Bolt run - “the fastest man alive”? Or the women’s gymnastics team, or the women’s soccer team, or the young American diver who shocked the diving world by winning the gold medal? It was all just wonderful. But you know what I always find really, really inspiring? It’s the closing ceremonies. No, not the opening ceremonies, although this year’s was exceptional, with the Queen appearing with James Bond and all. But the closing ceremonies are always wonderful for one big reason, in my opinion - that all of the athletes come on to the field in a group - all nations, all athletes, all sports - one great, huge group of humanity. They join together across competitive boundaries, and national boundaries, and ethnic boundaries, and language boundaries - they forget all of that and just revel in joy together at what they’ve experienced at the Games! It is absolutely wonderful, and I truly believe, in my heart of hearts, that it is a portrait of the coming kingdom of God - where all dwell together in harmony, as one. -

Digital Commons @ Salve Regina

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Student Newspapers Archives and Special Collections 4-1-1979 Nautilus, Vol. 32 No. 5 (Apr 1979) Salve Regina College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/student-newspapers Recommended Citation Salve Regina College, "Nautilus, Vol. 32 No. 5 (Apr 1979)" (1979). Student Newspapers. 51. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/student-newspapers/51 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEWPORT COLLEGE - SALVE REGINA April 1979 Celebrate Fifty Years As Mercy by JOANNE MAZNICKI TEBTAMEJJ:1!'0F CY It is with the utmost admira tion and honor that we the college Mercy knows no autumn or ~;a~t-ti~ community wish to extend our No death or dying except (.§>~1).__t,,t 4-..~ot Mercy. congratulations to Sister Mary Its response is always j~ous,'ffi s"tflt-giving, Jean Tobin, Sister Mary Eloise Always healing in its Ji'uC.h;<' o"" '?,~ Tobin, Sister Mary Loretto O'Con Always filled with 1.wp"lf i~·'it\..._Wmpassion. _cQ. , nor on their Golden Jubilee. This Its ministry enco7JJ?ifs~'i' azfJ;'need of every .-and degree, year marks their 50th year living Seeking only to:,:provt)e, f:o'uplift to console. and working as Sisters of Mercy. Its light illumff,fJs e/e r#id's darkness opening it to infinite horizons. -

Leave to Beaver Show

Leave to beaver show Its reception led to a new first-run, made-for-cable series, The New Leave It to Beaver (–), with Beaver and Production · Themes and recurring · Cancellation and · Media information. Comedy · The misadventures of a suburban boy, family and friends. Videos. Leave It to Beaver -- Trailer for Leave It to Beaver: The Complete Series. Comedy · The Cleavers are an all-American family living in Ohio - wise father Ward, loving .. Barbara Billingsley who played Aunt Martha, was the original June Cleaver in the television show "Leave It to Beaver" (). See more». I knocked on a door and a woman answered. I told her, "You must be lost, let me know you where the kitchen is. It's been 56 years since a cute little munchkin named Theodore entered our lives as "The Beaver" in an all-American show about suburban. Leave It to Beaver is one of the first primetime sitcom series written from a child's point of view. Like several television dramas and sitcoms of. One common criticism of Leave It to Beaver is that June, the Cleaver the first season of the show; she started wearing heels at the suggestion. Leave It to Beaver also went out on its own terms, as we will see. Let's take a look at some fascinating facts about the show that will make you. One of television's most iconic series, 'Leave It to Beaver' follows the adventures of inquisitive but often naive Theodore "The Beaver" Cleaver. Along with. The very first episode of classic television show Leave it to Beaver almost never made it on air, according to the show's star Jerry Mathers. -

Name That Pet! / Naomi Jones

Cousin Alice’s Press 14925 Magnolia Blvd., Suite 311 Sherman Oaks, CA 91403-1331 Copyright © 2004 by Naomi Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in whole or in part, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher. ISBN: 0-9719786-3-8 Cover graphics and book design by Syzygy Design Group, Inc. Cover illustration by Susan Gal Illustration Interior illustrations by Tanya Stewart Illustration Printed by United Graphics Inc. Printed in the United States of America First Printing: October 2004 Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Jones, Naomi Name that pet! / Naomi Jones. -- 1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 0-9719786-3-8 1. Pets--Names. I. Title. SF411.3.L54 2004 929.9’7 QBI02-200487 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING ABOUT “NAME THAT PET!” “ ‘Name That Pet!’ is one of those funny, uncategorizable books that are just for pet lovers. It is really a great book!” Lisa Ann D’Angelo, Managing Editor, Book Review Café “Pet naming has become one of the first emotional connections we make with our new friend. The author has included humorous, and both contemporary and historical names–along with defini- tions and references. This is a fun book to read and useful in its own way.” Susan J. Richey, Librarian, Santa Monica Public Library “My wife and I were amazed at the scope, details and fun in reading Ms. -

Puerto Rican History Observance Month Begins Weather

Puerto Rican History Observance Month begins See page 9 (ftmtttttiait flatlg (Jkmjma Serving Storrs Since 1896 Vol. LXXXVII No. 102 The University of Connecticut Monday, April 2, 1984 Congress to Israelis fire on Syrian debate deficit, positions in Lebanon military aid WASHINGTON (AP)— BEIRUT (AP)—Israeli tanks shelled positions in Syrian-held Congress this week will be Bekaa Valley Sunday for the first time in a year and Prime Minister struggling with two volatile Shafik Wazzan met with the Soviet ambassador and criticized the election-year issues- United U.S. failure to secure an Israeli withdrawal. States military involvement in The rightist Christian Voice of Lebanon radio said Israeli tanks Central America and how to took positions on hills just north of the village of Medoukha, reduce enormous federal about 30 miles southeast of Beirut, and shelled Syrian budget deficits. positions. The Senate has alloted It also said there were heavy exchanges near the villages of nearly 50 hours' debate begin- Sultan Yacoub, Yanta and the western slopes of Mount Hermon ning Monday on President whose summit is at the Syrian-Lebanese border, 40 miles Reagan's bid for 161.7 million southeast of the capital. in emergency military aid for The Israeli military command said its artillery attacked and El Salvador, down from the destroyed two guerrilla command posts in the Bekaa Valley that $93 million he originally had been used to prepare attacks on Israeli troops. It said the wanted. shelling was a response to recent attacks that wounded eight Both the House Foreign Israeli soldiers. Affairs Committee and the It was the first time in at least a year that Israel used artillery on Senate Foreign Relations guerrillas in Syrian-held Lebanese areas, although Israel has Committee are studying used planes against them. -

Edward Jurist Papers, 1940-1979

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8n58ppd No online items Finding Aid for the Edward Jurist papers, 1940-1979 Processed by Arts Special Collections staff, pre-1999; machine-readable finding aid created by Julie L. Graham and Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Edward Jurist PASC 122 1 papers, 1940-1979 Title: Edward Jurist papers Collection number: PASC 122 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 30.0 linear ft.(65 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1940-1979 Abstract: Ed Jurist had a career as a prolific television producer and writer. The collection consists of script files for radio and television productions, casting files of resumes and photographs, and a small amount of personal papers and printed materials. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Jurist, Edward Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

CV Training Packet

BASIC TRAINING FOR CONSERVATORS TRAINING PACKET · TABLE OF CONTENTS Resource page Page2 List of formsyou may need to use Page3 Sample case of June Cleaver Page 4 Facts Page 4 Certified Lettersof Conservatorship Pages 5 & 6 Inventory Pages 7& 9 Proof of Service - Inventory Page 10 Amended Inventory Pages11 -1 3 Proof of Service - Amended Inventory Page 14 Account of Fiduciary Pages15 -1 6 Financial Institution Statements Pagys17 -2 3 Proof of Service - Account Page24 Updated Letters of Conservatorship Pages 25 -2 6 Petition to Allow Account Page 27 Notice of Hearing-Account Page 28 Proof of Service of Petition to Allow Account Page 29 P�tition Regarding Real Estate/Dwelling Page s 30 -32 Tax Statement Page33 Notice of Hearing-Sale of Real Estate Page34 Proof of Service - Petition for Approval of Sale Page35 Notice of Deficiency Pages 36 -37 Order of suspension Page38 Petition and Order Page3 9 Petition and Order to Use Funds Page40 Proof of Restricted Account (Minors) Page41 1 CONSERVATOR BASIC TRAINING CLASS RESOURCE PAGE Oakland County Probate Court 1200 N. Telegraph Road, Dept. 457 Pontiac Ml 48341-0457 Telephone: 248-858-0260 Fax: 248-452-2016 Court Administrator Edward A. Hutton Ill 248-858-5603 Probate Register Barbara P. Andruccioli 248-858-0282 Helpful Websites: OAKLAND COUNTY PROBATE COURT General information, forms, procedures, FAQs, contacts www.oakgov.com/courts/probate Click on Guardianships/Conservatorships from the home page. SCAO�PPROVED FORMS The complete source for all state court-approved forms. https://courts.michigan.gov/Administration/SCAO/Forms/Pages/Conservator.aspx You may access other forms from the dropdown menu on left under "search for a court form." MICHIGAN COMPILED LAWS (MCLs) The complete source for all Michigan laws. -

Ilaiirl|Palpr Bpralji ) Manchester — a City of Village Charm

MOR l •S81 ilaiirl|palpr BpralJi ) Manchester — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents Saturday, Oct. 3.1987 >teer- ggar, itereo ling, 1 TIDE TURNS AGAINST BORK 0- 2721-5 Reagan fights for Integrity and independence’ of judicial system ... page 3 1- 1631-5 4-0925-5 2- 2837-5 4-1247-5 0-3582-0 8-3870-0 8-4093-0 j ' w - ‘s 8-4808-0 0-5817-0 ” A f ' -1 0-0723-0 8-8098-0 ' - • >r’‘- ^ ’■’rU / 'L ...;. i - V - 'i • 7-2888-0 0-8803-0 0-50154) 0-8358-0 7- 5204-0 4-1204-5 Get out 8- 5483-0 ■V=<3 7-5280-0 your 4-1314-5. woolies ;» AM B-e 0- 270 5 A bitter winter is 1- 1411 5 predicted as a wooliy 8-5911 0 bear caterpiiiar 8-8901 |0 “whispers” to Sam 8-50U ‘0 Tayior, the annual ism '■9^ 2-: 5 forecaster in Lancas '40-0 ter, Pa. Tayior deter '50-5 mines the forecast 'St ~5 ^-231 from the color of the 0 -2 W 5 caterpillar’s coat. 'M 2-240»S AP photo 4-1216-5 4-1261-5 4- 1272-5 1960-1987(Swx) 1987 6-5913-0 Iran threatens .ralMOM*^ 6-5914-0 1M 7 6-5918-0 15.9%I 6-5954-0 a confrontation 6- 0804-0 7- 5290-0 7-5201-0 Rafshanjani says Jobless 0-2804-5 6-4005-0 war with U.S. will 6- 4007-0 rate falls 7- 5000-0 be sw eet..