Northampton 1460

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Football Clubs and Teams

APPENDIX 1: FOOTBALL CLUBS AND TEAMS Team Main Ground Team Team Age Team Gender Category Group Billing United - Adult Ladies GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 11v11 Open Aged Female Billing United - Adult Mens GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 11v11 Open Aged Male Billing United - Adult Vets GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 11v11 Veterans Male Billing United Youth U10 GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 7v7 U10 Mixed Billing United Youth U12 GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 9v9 U12 Mixed Billing United Youth U13 RECTORY FARM OPEN SPACE 11v11 Youth U13 Mixed Billing United Youth U14 RECTORY FARM OPEN SPACE 11v11 Youth U14 Mixed Billing United Youth U7 GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 5v5 U7 Male Billing United Youth U8 GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 5v5 U8 Mixed Billing United Youth U9 GREAT BILLING POCKET PARK 7v7 U9 Mixed Brixworth Juniors U9 Girls DALLINGTON PARK 5v5 U9 Female Duston Dynamo First DUSTON SPORTS CENTRE 11v11 Open Aged Male East Hunsbury FC U9 GOALS SOCCER CENTRE (NORTHAMPTON) Mini Soccer U9 Male Hardingstone Sun Inn 1st Victoria Park 11v11 Open Aged Male Northampton 303 Polish Mini Soccer U7 DALLINGTON PARK 5v5 U7 Male Northampton 303 Polish Mini Soccer U7 blues DALLINGTON PARK 5v5 U7 Male Northampton 303 Polish Mini Soccer U8 RACECOURSE 5v5 U9 Male Northampton 303 Polish Mini Soccer U8 reds RACECOURSE 5v5 U8 Male Northampton A.C. Squirrels First DUSTON SPORTS CENTRE 11v11 Open Aged Male Northampton Abington FC First KINGSTHORPE RECREATION GROUND 11v11 Open Aged Male Northampton Abington Stanley First RACECOURSE 11v11 Open Aged Male Northampton AFC Becket Blues RACECOURSE -

Your Rubbish Is Your Responsibility

Remember, we are cracking down on fly tipping – it is a crime that affects you, your family and your community, and more importantly your pocket as a Northamptonshire tax payer. We need your help to track down fly tipping offenders. Is th is y o Find your nearest Household Waste Recycling Centres Tip off your local council in total confidence if you u There are ten sites across the county, check online witness fly tipping or have any suspicions. r s at www.northamptonshire.gov.uk/recyclingcentres for ? opening times. All sites are closed on Christmas Day, Further Information Boxing Day and New Years Day. For further information contact your local council or check their website. Brixworth Corby Scaldwell Road Kettering Road Contact details for your local council: Brixworth Weldon Northants, NN6 9RB Northants, NN17 3JG Daventry Kettering Corby Borough Council: Browns Road Garrard Way Northampton Borough Off Staverton Road Telford Way Industrial Estate Council: 01536 464000 Daventry Kettering www.corby.gov.uk Northants, NN11 4NS Northants, NN16 8TD 01604 837837 www.northampton.gov.uk Northampton – Ecton Lane Northampton – Sixfields Lower Ecton Lane Walter Tull Way Great Billing Weedon Road Northampton, NN3 5HQ Via Sixfields Leisure roundabout East Northamptonshire Rushden Northampton, NN5 5QL Daventry District Council: Council: Your rubbish is Northampton Road 01832 742000 East of Sanders Lodge on Towcester 01327 871100 www.daventrydc.gov.uk www.east- the old A45 road Old Greens Norton Road northamptonshire.gov.uk your responsibility Rushden Towcester Northants, NN10 6AL Northants, NN12 8AW Make sure it doesn’t get dumped Wellingborough Wollaston Kettering Borough Paterson Road Grendon Road Council: A guide for householders Finedon Road Wollaston, NN29 7PU 01536 410333 Industrial Estate www.kettering.gov.uk South Northamptonshire Wellingborough Council: Northants, NN8 4BZ 01327 322322 This information can be made available in other languages and formats upon request. -

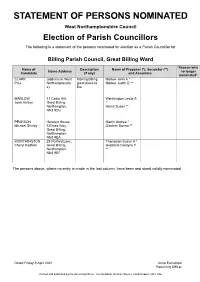

Parish Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Billing Parish Council, Great Billing Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* CLARK (address in West Making Billing Marlow John A * Paul Northamptonshir great place to Marlow Judith E ** e) live MARLOW 11 Cattle Hill, Worthington Leslie S John Ashley Great Billing, * Northampton, Harris Susan ** NN3 9DU PEARSON Herewyt House, Martin Andrea * Michael Shirley 5 Elwes Way, Gardner Donna ** Great Billing, Northampton, NN3 9EA WORTHINGTON 28 Penfold Lane, Thompson Susan A * Cheryl Redfern Great Billing, Goddard Carolyne T Northampton, ** NN3 9EF The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Guildhall, St Giles Square, Northampton, NN1 1DE STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Kingsthorpe, Spring Park Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* AZIZ 201 Abington Conservative Naeem Abdullah * Mohammed Avenue, Party Candidate Virk Naeem R ** Northampton, NN1 4PX BRADY (address in West Halliday Stephen J * Sean Northamptonshir Brady Alannah ** e) KUMAR 11 Crawley Smith Philippa M * Dilip Close, Northfield Smith Alan R ** Way, Kingsthorpe, Northampton, NN2 8BA LEWIN 145 Sherwood Smart Robert M * Bryan Roy Avenue, Mace Jeffrey S ** Northampton, NN2 8TA MILLER 43 Lynton Green Party Ward-Stokes Gillian Elaine Mary Avenue, D * Kingsthorpe, Miller Stephen M ** Northampton, NN2 8LX NEWBURY 4 St Davids Conservative Batchlor Lawrence Arthur John Road, Candidate W.J. -

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering 1 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 INTRODUCTION This locality profile expands on the findings of the main document and aims to build a localised picture of those clusters of indicators which require focus from the Council and partner agencies. Wherever possible, data has been extracted at locality level and comparison with the rest of the county, the region and England has been carried out. MAIN FINDINGS The areas in which Kettering performs very similarly to the national average are detailed below. The district has no indicators in which it performs worse than the national average or the rest of the county: Life expectancy at birth for females (third lowest in the county) School exclusions Under 18 conceptions Smoking at the time of delivery Excess weight in Reception and Year 6 pupils Alcohol specific hospital stays in under 18s (second highest rate in the county) Admissions to A&E due to self-harm in under 18s (second highest in the county) 2 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 KETTERING OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHY As a locality, a number of Kettering’s demographics conform with the Northamptonshire picture, particularly around household deprivation, occupational structure, qualifications and age. Kettering has a population of around 95,700, the second largest in the county, and the second highest number of households, although the average household size is second lowest in Northamptonshire. The area is predominantly White with a small BME population. Rather than spread evenly across a number of ethnic groups, over 50% fall within the Asian community. -

The Art Department Visit London and Northampton

Issue No. 2 JANUARY 2017 Sir Edward Garnier The Art Department visit visits Brooke House College London and Northampton After arriving at the Tate Modern several hours were spent looking carefully at the different exhibitions and paintings. The group were amazed at all of the different ideas, materials and techniques that filled the rooms. From film, sound, and photography to huge three dimensional structures and abstract colourful paintings the students were inspired with how to develop their own work back in the art class. Our Local Member of Parliament, Sir Edward Garnier QC paid the After lunch the group crossed the Millennium Bridge with the school a visit in early December, amazing views of London over the Thames and took the tube to much to the delight of the A Level Leicester Square. After visiting China Town they then went to Government & Politics students. the National Gallery in Trafalger Square where they were able to Sir Edward spoke to the students look closely at paintings from 1600-1940’s. These were a about his role as an MP and then complete contrast to the Tate Modern collection and gave the answered many questions from group the opportunity to be able to contrast materials, the students on topics far and techniques and subject matter in art across time and place. wide. Needless to say Brexit, the On Tuesday 6th December 2016 students from Art Foundation referendum and a recent visit and Art A Level visited the Park Avenue Campus in Northampton from the President of Nigeria were University for an exciting afternoon of printmaking. -

Heritage Assets Tyrley

Loggerheads Parish Tyrley Ward Heritage Assets Tyrley Ward Tyrley A settlement recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086 “lying within Hodnet Hundred (in Shropshire). William also holds Tyrley of the Earl Roger. Wulfric and Ravensward held it as two manors; they were free. One hide paying tax. There is land for two ploughs. There are four villagers and one slave with one plough. The value was 17 shillings and is now 20 shillings.” Recorded as a suspected lost village situated near the modern settlement of Hales by Bate and Palliser. No date of desertion is given. Jonathan Morris, in his book ‘The Shropshire Union Canal’ (1991), explains the origin of the name Tyrley. Tyrley Castle Farm is on the site of a Saxon castle which was built on a man-made mound in a field. The Saxon for mound is ‘tir’ and for field ‘ley’, hence Tirley which has become Tyrley Tyrley Wharf Page 68 Loggerheads Parish Tyrley Ward Heritage Assets Forming part of the Tyrley Conservation Area DC, The delightful collection of grade two listed buildings at Tyrley Wharf on the Shropshire Union Canal was constructed by the Peatswood Estate to coincide with the completion of the canal. There were originally seven individual cottages built to house estate workers and a stable to accommodate the horses used to tow canal barges. Constructed in brown brick with ashlar dressings, slate roof with coped verges on stone kneelers, multi-paned 2- light casements in plastered stone surrounds to first, second and fourth bays from left, blind round-headed brick opening to third; 3 lean-to timber porches on brick dwarf walls with slate roofs to front over cambered doorways with boarded doors; prominent paired and rebated ridge stack to left (shared between Nos.30 and 31) and taller ridge stack to right (to No.32). -

Hardingstone Conservation Area Appraisal

HARDINGSTONE C O N S E R V A T I O N A R E A War Memorial, The Green CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL & MANAGEMENT PLAN Planning Policy & Conservation Section Northampton Borough Council February 2009 Hardingstone Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal & Management Plan Contents Consultation details next page Re-appraisal Introduction...................................................................................................1 The Importance of Conservation Areas Planning policy context Summary of special interest Location & Context......................................................................................2 Historic Development ..................................................................................3 Plan Form .......................................................................................................6 Character ......................................................................................................6 Character Areas...........................................................................................8 Building materials and local details.........................................................11 Trees and green spaces............................................................................11 Important Green Setting of the Conservation Area .............................12 Key views and vistas...................................................................................12 Buildings making a positive contribution to the area...........................12 Summary of issues.......................................................................................13 -

Great Billing, Northamptonshire

Great Billing, Northamptonshire A high specification brick under tile five double bedroom contemporary style detached house with an integral double garage, driveway parking and an enclosed rear garden. The property was built in 2008 and has underfloor heating Contemporary detached house Linrey throughout, and is wired for phone, TV, data and music with Five bedrooms; five bathrooms Five reception rooms Wellingborough Road, Great Billing, speakers fitted in all the ground floor reception rooms and the bedrooms. The entrance hall has engineered oak flooring, an Underfloor heating Northamptonshire, NN3 9BQ under stairs cupboard and a two piece cloakroom. The sitting Oak doors room has an inset gas log effect fire, and leaded light doors and Accommodation of 3,004 sq. ft. windows to the rear, and the dual aspect dining room has Mature gardens Driveway parking and a double garage 5 bedrooms windows to both sides and a door to the garage. There is also a family room, and a study with engineered oak flooring and two 5 reception rooms built-in cupboards. The triple aspect garden room has a vaulted Additional Information ceiling, a tiled floor, and French doors to the patio. Mains water, Gas, Electricity 5 bathrooms The Local Authority is West Northamptonshire Council The master bedroom overlooks the front and has a dressing area The property is in council tax band G To be confirmed with fitted furniture, and a five piece en suite bathroom. There are four further bedrooms which all have fitted wardrobes and en suite shower rooms. Kitchen/Breakfast Room The kitchen/breakfast room has windows to the side and rear. -

October 2004

October 2004 1. INTRODUCTION: 1.1 Space within Northampton is at a premium and is subject to many demands for its use (recreational, residential, retail, wholesale, industrial etc.). This strategy makes the case for protection of open space for formal recreational use, namely sports use. Sports use of open space requires adequate provision of playing pitches and ancillary facilities (changing, showering, and toilet facilities) suitable for the sports being played. 1.2 The analysis on which this strategy is based involves the supply and demand of pitch space for the four main pitch sports played formally within the town: Association Football; Rugby Football; Cricket; and Hockey (hockey is a slightly unusual case as it is no longer played competitively on grass, but requires a specially constructed artificial turf pitch [ATP]). 1.3 The provision and/or loss of playing pitches can be a contentious issue for sport in this country and the current Government has identified, within “A Sporting Future for All: The Government’s Plan for Sport”, that the rate at which playing pitches are being lost to development needs to be greatly reduced. An important tool in achieving this aim is for each local authority to complete a playing pitch audit and develop a local playing fields strategy. This is reinforced within Planning Policy Guidance note PPG17, which states, “to ensure effective planning for open space, sport and recreation it is essential that the needs of local communities are known. Local authorities should undertake robust assessments of the existing and future needs of their communities for open space, sports and recreational facilities”. -

DELAPRE from Medieval Nunnery to Modern Public Park, Delapre Has a Rich and Varied History

DELAPRE From medieval nunnery to modern public park, Delapre has a rich and varied history. Lying within a stone’s throw of Northampton’s busy town centre, the varied paths and trails detailed in this leaflet will lead you via parkland and woods, village streets and ancient buildings, back in time to a medieval world of royalty, religion and war. Delapre Lake DELAPRE Lying on the southern boundary of Northampton, Delapre & Hardingstone Delapre, with its 550 acres of parkland and gardens, has a * long and eventful history. From its beginnings as a Cluniac nunnery, Delapre was destined to become the temporary resting place of an English Queen, a War of the Roses battlefield, an 18th century country house and park, a 20th century home for Northamptonshire records ... until finally it became an attractive public park and home to Delapre Golf Complex. Delapre Park is approximately one mile, and Hardingstone HARDINGSTONE less than three miles from Northampton town centre. Lying on the outskirts of Northampton, Hardingstone’s For information about public transport to Delapre and ironstone and brick buildings are typical of many Hardingstone, please contact Traveline on 0870 608 2608. Northamptonshire villages. Many of the brick terraced Car parking is available at Delapre Abbey (approach via the houses in the High Street were built by the Bouverie driveway from London Road) and south of Delapre Lake Queen Eleanor’s Cross family (owners of Delapre Abbey from 1764 to 1946). (via the Delapre Golf Complex turnoff from the A45). Also in the High Street is the parish church of St. Edmund If you wish to report any problems with any of the routes 10 . -

Northampton Bus Services Town Centre

Northampton Bus Services The below table shows a summary of the Northampton town buses local to the university sites, this information is accurate as of June 2018, however please verify the information here: http://www3.northamptonshire.gov.uk/councilservices/northamptonshire- highways/buses/Pages/default.aspx For up to date information and to see all of the bus networks use the Northants County Council town and county bus maps. Destination Route Route Description Frequency Number Town Centre/Bus 1 Town Centre – Monday – Sunday Station Blackthorn/Rectory Farm (Monday – Saturday (Short walk to: The (Hourly service includes: town daytime only) Platform, The Innovation centre - General Hospital – Centre, St John’s Halls & Grange Park) House and Waterside) 2 Camp Hill - Town Centre - Monday – Sunday Blackthorn/Rectory Farm 5 St. Giles Park - Town Centre – Monday – Saturday Southfields peak 7 / 7A Grange Park - Wootton - Monday – Friday Hardingstone - Town Centre - (Weekends reduced Moulton Park service) 8 Kings Heath – Town Centre – Monday – Saturday Blackthorn/Rectory Farm peak 9/9A Town Centre – Duston Monday – Saturday peak 10/X10 West Hunsbury - Town Centre Monday – Saturday – Parklands - Moulton peak 12 Kings Heath - Town Centre – Monday - Sunday East Hunsbury 15/ 15A Moulton Park* - Acre Lane - Monday - Sunday Town Centre - St. Crispin 16 Obelisk Rise - Town Centre – Monday - Sunday Ecton Brook 31 Town Centre – Kings Heath Monday - Sunday 33/33A Northampton – Milton Keynes Monday – Saturday peak Bedford Rd/Waterside 41 Northampton – -

HP Source Issue 12 April 2021

HPSource Hardingstone’s Newsletter Issue 12 April - May 2021 To be replaced with better picture. HP Source is a bi-monthly newsletter, funded by Hardingstone Parish Council, compiled and edited by a team of volunteers for Hardingstone Village. 1 From your editorial team We are including several articles from villagers which we editor, and if possible should be restricted to around 250 didn’t have room for last time, together with some new words. ones. We hope that you find them interesting, and if you The editor has complete discretion to omit or to edit can help by providing an article or photographs for future submissions. Deadlines for sending items are given below. issues we would welcome your input. Articles, notices and advertisements published in the *On April 1st the Borough and County Councils will be newsletter do not necessarily represent the views of the replaced by West Northamptonshire Council (WNC). As editorial team or the Parish Council, and we take no the councillors to WNC will not be decided until elections responsibility for the content. We do not endorse in May, the former councillors shown in ‘Useful Contacts’ products, services, events, businesses, organisations or below should be able to provide support until then. individuals featured and / or advertised in the newsletter. As we recover from the lockdown, we hope to include KAPH, the editorial team. items and information from Hardingstone organisations Send your items to: [email protected] and clubs again. We work to agreed editorial and or deliver to: The Parish Room High Street NN4 6DA advertising guidelines.