Unusual Invertebrates and Fish Observed in the Gulf of Alaska, 2004–2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Cycle and Early Development of the Thecosomatous Pteropod Limacina Retroversa in the Gulf of Maine, Including the Effect of Elevated CO2 Levels

Life cycle and early development of the thecosomatous pteropod Limacina retroversa in the Gulf of Maine, including the effect of elevated CO2 levels Ali A. Thabetab, Amy E. Maasac*, Gareth L. Lawsona and Ann M. Tarranta a. Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543 b. Zoology Dept., Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University in Assiut, Assiut, Egypt. c. Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, St. George’s GE01, Bermuda *Corresponding Author, equal contribution with lead author Email: [email protected] Phone: 441-297-1880 x131 Keywords: mollusc, ocean acidification, calcification, mortality, developmental delay Abstract Thecosome pteropods are pelagic molluscs with aragonitic shells. They are considered to be especially vulnerable among plankton to ocean acidification (OA), but to recognize changes due to anthropogenic forcing a baseline understanding of their life history is needed. In the present study, adult Limacina retroversa were collected on five cruises from multiple sites in the Gulf of Maine (between 42° 22.1’–42° 0.0’ N and 69° 42.6’–70° 15.4’ W; water depths of ca. 45–260 m) from October 2013−November 2014. They were maintained in the laboratory under continuous light at 8° C. There was evidence of year-round reproduction and an individual life span in the laboratory of 6 months. Eggs laid in captivity were observed throughout development. Hatching occurred after 3 days, the veliger stage was reached after 6−7 days, and metamorphosis to the juvenile stage was after ~ 1 month. Reproductive individuals were first observed after 3 months. Calcein staining of embryos revealed calcium storage beginning in the late gastrula stage. -

Seasonal and Interannual Patterns of Larvaceans and Pteropods in the Coastal Gulf of Alaska, and Their Relationship to Pink Salmon Survival

Seasonal and interannual patterns of larvaceans and pteropods in the coastal Gulf of Alaska, and their relationship to pink salmon survival Item Type Thesis Authors Doubleday, Ayla Download date 30/09/2021 16:15:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/4451 SEASONAL AND INTERANNUAL PATTERNS OF LARVACEANS AND PTEROPODS IN THE COASTAL GULF OF ALASKA, AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO PINK SALMON SURVIVAL By Ayla Doubleday RECOMMENDED: __________________________________________ Dr. Rolf Gradinger __________________________________________ Dr. Kenneth Coyle __________________________________________ Dr. Russell Hopcroft, Advisory Committee Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Brenda Konar Head, Program, Marine Science and Limnology APPROVED: __________________________________________ Dr. Michael Castellini Dean, School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences __________________________________________ Dr. John Eichelberger Dean of the Graduate School __________________________________________ Date iv SEASONAL AND INTERANNUAL PATTERNS OF LARVACEANS AND PTEROPODS IN THE COASTAL GULF OF ALASKA, AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO PINK SALMON SURVIVAL A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Ayla J. Doubleday, B.S. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2013 vi v Abstract Larvacean (=appendicularians) and pteropod (Limacina helicina) composition and abundance were studied with physical variables each May and late summer across 11 years (2001 to 2011), along one transect that crosses the continental shelf of the subarctic Gulf of Alaska and five stations within Prince William Sound (PWS). Collection with 53- µm plankton nets allowed the identification of larvaceans to species: five occurred in the study area. Temperature was the driving variable in determining larvacean community composition, yielding pronounced differences between spring and late summer, while individual species were also affected differentially by salinity and chlorophyll-a concentration. -

Diel Vertical Distribution Patterns of Zooplankton Along the Western Antarctic Peninsula

W&M ScholarWorks Presentations 10-9-2015 Diel Vertical Distribution Patterns of Zooplankton along the Western Antarctic Peninsula Patricia S. Thibodeau Virginia Institute of Marine Science John A. Conroy Virginia Institute of Marine Science Deborah K. Steinberg Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/presentations Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Oceanography Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Thibodeau, Patricia S.; Conroy, John A.; and Steinberg, Deborah K.. "Diel Vertical Distribution Patterns of Zooplankton along the Western Antarctic Peninsula". 10-9-2015. VIMS 75th Anniversary Alumni Research Symposium. This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diel Vertical Distribution Patterns of Zooplankton along the Western Antarctic Peninsula Patricia S. Thibodeau, John A. Conroy & Deborah K. Steinberg Introduction & Objectives Results: vertically migrating zooplankton Conclusions The Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) region has undergone significant Metridia gerlachei (copepod) Ostracods • Regardless of near continuous light in austral summer, some zooplankton warming and decrease in sea ice cover over the past several decades species still undergo DVM along the WAP. This is supported by one other (Ducklow et al. 2013). The ongoing Palmer Antarctica Long-Term Ecological North North study (Marrari et al., 2011) for a location in Marguerite Bay. Research (PAL LTER) study indicates these environmental changes are • The strength of DVM differed along a latitudinal gradient with some species affecting the WAP marine pelagic ecosystem, including long-term and spatial showing stronger migration in the north (e.g., krill) and some in the south shifts in relative abundances of some dominant zooplankton (Ross et al. -

Umitaka-Maru" Expedition, Part 3 Thecosomatous Pteropoda Collected by the Training Vessel "Umitaka-Maru" from the Antarctic Waters in 1957

J. Fac. Fish. Anim. Husb. Hiroshima Univ. (1%3), 5 (1): 95-105 Reports on the Biology of the "Umitaka-Maru" Expedition, Part 3 Thecosomatous Pteropoda Collected by the Training Vessel "Umitaka-Maru" from the Antarctic Waters in 1957 Iwao TAKI Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Fisheries and Animal Husbandry, Hiroshima University, Fukuyama, Japan and Takashi OKUTANI Tokai Regional Fisheries Research Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan INTRODUCTION Considerable works on the antarctic Pteropodan fauna have been published until to-day. The important contributions among them are those by MEISENHEIMER (1906) on the samples of the "Deutsche Siidpolar-Expedition", by ELIOT (1907) of the "National Antarctic Expedition" and by MASSY (1920, 1932) of the "Terra Nova" and "Discovery" Expeditions. Materials of the "Challenger" Expedition reported by PELSENEER (1888), those of the "Valdivia" Expedition by MEISENHEIMER (1905) and the "Dana" Expedition by TESCH ( 1946, 1948) include some specimens found in the sub-antarctic and arctic areas. The Training Vessel "Umitaka-Maru" of the Tokyo University of Fisheries made some plankton-net tows in the Antarctic waters during her cruise in the service of escortship of the R. V. "Soya" for the Japanese Antarctic Expedition in 1956. By the courtesy of Professor Jiro SENO of the University, gastropods were sorted out from the plankton samples then collected and thereafter placed under our disposal. The present material mainly consists of thecosomatous pteropods. Their shells are mostly worn out by the action of formalin. We wish to express our sincere gratitude to Prof. J. SENO of the Tokyo University of Fisheries, who managed in field collection of the present samples and arranged them for us to study. -

The Influence of Depth on Mercury Levels in Pelagic Fishes and Their Prey

The influence of depth on mercury levels in pelagic fishes and their prey C. Anela Choya,1, Brian N. Poppb, J. John Kanekoc, and Jeffrey C. Drazena aDepartment of Oceanography, University of Hawaii, 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, HI 96822; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii, 1680 East-West Road, Honolulu, HI 96822; and cPacMar Inc., 3615 Harding Avenue, Suite 409, Honolulu, HI 96816 Edited by David M. Karl, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved June 23, 2009 (received for review January 21, 2009) Mercury distribution in the oceans is controlled by complex bio- temperature, algal concentrations) (11), and perhaps most com- geochemical cycles, resulting in retention of trace amounts of this monly, size (12). Despite extensive measurements of mercury in metal in plants and animals. Inter- and intra-specific variations in both the environment and biota, it is still not known why, mercury levels of predatory pelagic fish have been previously irrespective of size, some fish species have elevated mercury linked to size, age, trophic position, physical and chemical envi- concentrations and others do not. ronmental parameters, and location of capture; however, consid- Biogeochemical studies detailing the movement of mercury erable variation remains unexplained. In this paper, we focus on between air, land, and ocean reservoirs have offered insight into differences in ecology, depth of occurrence, and total mercury where mercury may be distributed in the marine environment levels in 9 species of commercially important -

MOLLUSCA Nudibranchs, Pteropods, Gastropods, Bivalves, Chitons, Octopus

UNDERWATER FIELD GUIDE TO ROSS ISLAND & MCMURDO SOUND, ANTARCTICA: MOLLUSCA nudibranchs, pteropods, gastropods, bivalves, chitons, octopus Peter Brueggeman Photographs: Steve Alexander, Rod Budd/Antarctica New Zealand, Peter Brueggeman, Kirsten Carlson/National Science Foundation, Canadian Museum of Nature (Kathleen Conlan), Shawn Harper, Luke Hunt, Henry Kaiser, Mike Lucibella/National Science Foundation, Adam G Marsh, Jim Mastro, Bruce A Miller, Eva Philipp, Rob Robbins, Steve Rupp/National Science Foundation, Dirk Schories, M Dale Stokes, and Norbert Wu The National Science Foundation's Office of Polar Programs sponsored Norbert Wu on an Artist's and Writer's Grant project, in which Peter Brueggeman participated. One outcome from Wu's endeavor is this Field Guide, which builds upon principal photography by Norbert Wu, with photos from other photographers, who are credited on their photographs and above. This Field Guide is intended to facilitate underwater/topside field identification from visual characters. Organisms were identified from photographs with no specimen collection, and there can be some uncertainty in identifications solely from photographs. © 1998+; text © Peter Brueggeman; photographs © Steve Alexander, Rod Budd/Antarctica New Zealand Pictorial Collection 159687 & 159713, 2001-2002, Peter Brueggeman, Kirsten Carlson/National Science Foundation, Canadian Museum of Nature (Kathleen Conlan), Shawn Harper, Luke Hunt, Henry Kaiser, Mike Lucibella/National Science Foundation, Adam G Marsh, Jim Mastro, Bruce A Miller, Eva -

Anatomical Considerations of Pectoral Swimming in the Opah, Lampris Guttatus Author(S): Richard H

Anatomical Considerations of Pectoral Swimming in the Opah, Lampris guttatus Author(s): Richard H. Rosenblatt and G. David Johnson Source: Copeia, Vol. 1976, No. 2 (May 17, 1976), pp. 367-370 Published by: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1443963 Accessed: 02/06/2010 14:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asih. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Copeia. http://www.jstor.org ICHTHYOLOGICAL NOTES 367 (1936). -

Genetic Population Structure of the Pelagic Mollusk Limacina Helicina in the Kara Sea

Genetic population structure of the pelagic mollusk Limacina helicina in the Kara Sea Galina Anatolievna Abyzova1, Mikhail Aleksandrovich Nikitin2, Olga Vladimirovna Popova2 and Anna Fedorovna Pasternak1 1 Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 2 Belozersky Institute for Physico-Chemical Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia ABSTRACT Background. Pelagic pteropods Limacina helicina are widespread and can play an important role in the food webs and in biosedimentation in Arctic and Subarctic ecosystems. Previous publications have shown differences in the genetic structure of populations of L. helicina from populations found in the Pacific Ocean and Svalbard area. Currently, there are no data on the genetic structure of L. helicina populations in the seas of the Siberian Arctic. We assessed the genetic structure of L. helicina from the Kara Sea populations and compared them with samples from around Svalbard and the North Pacific. Methods. We examined genetic differences in L. helicina from three different locations in the Kara Sea via analysis of a fragment of the mitochondrial gene COI. We also compared a subset of samples with L. helicina from previous studies to find connections between populations from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Results. 65 individual L. helinica from the Kara Sea were sequenced to produce 19 different haplotypes. This is comparable with numbers of haplotypes found in Svalbard and Pacific samples (24 and 25, respectively). Haplotypes from different locations sampled around the Arctic and Subarctic were combined into two different groups: H1 and H2. The H2 includes sequences from the Kara Sea and Svalbard, was present only in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic. -

Interannual Variability of Pteropod Shell Weights in the High-CO2 Southern Ocean

Interannual variability of pteropod shell weights in the high-CO2 Southern Ocean Donna Roberts, Will Howard, Andrew Moy, Jason Roberts, Tom Trull, Stephen Bray & Russ Hopcroft Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems Australian Government Cooperative Research Centre Department of Climate Change Motivation for Research Project • Atmospheric CO2 ⇑ • Ocean pH ⇓ 2- • [CO3 ] ⇓ . models suggest polar regions 2- will experience [CO3 ] below those favourable for aragonite 1 precipitation first . Southern Ocean a good place to look for impacts of ocean acidification on aragonite calcifiers 1 Orr et al. 2005. Nature: 437 Southern Ocean shelled pteropods: now SAZ-SENSE Voyage CEAMARC Voyage 44-54°S 140-155°E 62-67°S 138-146°E 17 Jan - 20 Feb 2007 23 Jan - 16 Feb 2008 1 2 3 1 2 1. Cavolinia tridentata f. atlantica 2. Clio cuspidata 3. Clio pyramidata f. antarctica 4 5 6 4. Clio pyramidata f. sulcata 5. Clio balantium (recurva) 6. Diacria rampali 7. Limacina helicina antarctica 7 8 9 8. Limacina retroversa australis * 9. Peracle cf. valdiviae * 1. Limacina helicina antarctica 2. Clio balantium Southern Ocean shelled pteropods: past • Sediment Traps . 47°S . 142°E . 2000 m trap . 4500 m water . 1997/98 - 2005/06 . each cup (21) treated with dense, buffered, * biocide solution and open from 5 - 60 days Southern Ocean shelled pteropods: past • How will we measure calcification response in Southern Ocean pteropods? 2- 1 . Foram shell weights ⇓ as surface water [CO3 ] ⇓ 1 mm . Pteropod shell weights? - recovered 5 traps in 9 years at 47°S - extracted 150µm - 1mm size fraction - dissolved organics in buffered 3% H2O2 - identified whole pteropod shells - batch weighed discrete taxa per cup (microbalance precision = 0.1µg) - accounted for non-uniform trap intervals 1 Barker & Elderfield. -

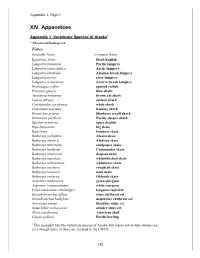

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Notes on the Systematics, Morphology and Biostratigraphy of Fossil Holoplanktonic Mollusca, 22 1

B76-Janssen-Grebnev:Basteria-2010 11/07/2012 19:23 Page 15 Notes on the systematics, morphology and biostratigraphy of fossil holoplanktonic Mollusca, 22 1. Further pelagic gastropods from Viti Levu, Fiji Archipelago Arie W. Janssen Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis (Palaeontology Department), P.O. Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; currently: 12, Triq tal’Hamrija, Xewkija XWK 9033, Gozo, Malta; [email protected] Andrew Grebneff † Formerly : University of Otago, Geology Department, Dunedin, New Zealand himself during holiday trips in 1995 and 1996, also from Viti Two localities in the island of Viti Levu, Fiji Archipelago, Levu, the largest island in the Fiji archipelago. Following an yielded together 28 species of Heteropoda (3 species) and initial evaluation of this material it remained unstudied, 15 Pteropoda (25 species). Two samples from Tabataba, NW however, for a long time . A first inspection acknowledged Viti Levu, indicate an age of late Miocene to early Pliocene. Andrew’s impression that part of the samples was younger Two samples from Waila, SE Viti Levu, signify an age of than the earlier described material and therefore worth Pliocene (Piacenzian) and closely resemble coeval assem - publishing. blages described from Pangasinan, Philippines. After the untimely death of Andrew Grebneff in July 2010 (see the website of the University of Otago, New Key words: Gastropoda, Pterotracheoidea, Limacinoidea, Zealand (http://www.otago.ac.nz/geology/news/files/ Cavolinioidea, Clionoidea, late Miocene, Pliocene, biostratigraphy, andrew_ grebneff.html) it was decided to restart the study Fiji archipelago. of those samples and publish the results with Andrew’s name added as a valuable co-author, as he not only collected the specimens but also participated in discussions on their Introduction taxonomy and age. -

Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Summer 2016 Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Linardich, Christi. "Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes" (2016). Master of Science (MS), Thesis, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/hydh-jp82 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES by Christi Linardich B.A. December 2006, Florida Gulf Coast University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BIOLOGY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2016 Approved by: Kent E. Carpenter (Advisor) Beth Polidoro (Member) Holly Gaff (Member) ABSTRACT HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Kent E. Carpenter Understanding the status of species is important for allocation of resources to redress biodiversity loss.