The Trial of the Peacock Generation Troupe: Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS MYANMA RAILWAYS Expert Group Meeting on the Use of New Technologies for Facilitation of International Railway Transport 9-12 December, 2019 Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar Ba Myint Managing Director Myanma Railways Ministry of Transport and Communications MYANMAR Contents . Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar . Formulation of National Transport Master Plan . Preparation for the National Logistics Master Plan Study (MYL‐Plan) . Status of Myanma Railways and Current Rail Infrastructure Development Projects . Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar 2 Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar Myanma’s Profile . Population – 54.283 Million(March,2018) India . Area ‐676,578 Km² China . Coastal Line ‐ 2800 km . Road Length ‐ approximately 150,000 km . Railways Route Length ‐ 6110.5 Km . GDP per Capita – 1285 USD in 2018 Current Status Lao . Myanmar’s Transport system lags behind ASEAN . 60% of highways and rail lines in poor condition Thailand . 20 million People without basic road access . $45‐60 Billion investments needs (2016‐ 2030) Reduce transport costs by 30% Raise GDP by 13% Provide basic road access to 10 million people and save People’s lives on the roads. 4 Notable Geographical Feature of MYANMAR India China Bangaladesh Lao Thailand . As land ‐ bridge between South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as with China . Steep and long mountain ranges hamper the development of transport links with neighbors. 5 Notable Geographical Feature China 1,340 Mil. India 1,210 mil. Situated at a cross‐road of 3 large economic centers. -

1 538055 / (+95) 1 2304999

Rangoon Private Hospitals Asia Royal Hospital 14 Baho Road, Sanchaung Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 538055 / (+95) 1 2304999 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.asiaroyalhospital.com/ Bumrungrad Clinic 77 Pyidaungsu Yeiktha Road, Dagon Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 2302420, 21, 22, 23 Website: www.bumrungrad.com/yangon-1 Note: Not open 24 hours International SOS Clinic Dusit Inya Lake Resort, 37 Kaba Aye Pagoda Road, Rangoon (+95) 1 657922 / (+95) 1 667866 Website: www.internationalsos.com/en/about-our-clinics_myanmar_3333.htm Pun Hlaing Siloam Hospital Pun Hlain Golf Estate Avenue, Hlaing Tharyar Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 3684336 Emergency Ambulance: (+95) 1 684411 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.punhlaingsiloamhospitals.com Samitivej International Clinic at Parami Hospital 11th Floor of Parami Hospital, 60 (G-1) New Parami Road, Mayangon Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 657987 / (+95) 1 657592 / +95 1 656732 / (+95) 1 660545 / (+95) 9 3333259 Email address: info@[email protected] Victoria (Witoriya) Hospital/LEO Medicare 68 Taw Win Street, 9 Mile, Mayangone Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 9666141 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.victoriahospitalmyanmar.com/ Rangoon Public Hospitals Yangon General Hospital Bogyoke Aung San Road 9 Ward, Latha Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 256112-131 Yangon Childrens Hospital (Ahlone) 2 Pyidaungsu Yeiktha Road, Ahlone Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 221421 / (+95) 1 222807 Yangon Mental Health Hospital Yhar Tar Gyi Ward, East Dagon Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 2306400 Yankin Childrens Hospital 90 Thitsa Road, Yankin Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 8550684-9 Rangoon Dental Care Dental Clinic Sakura Tower, 2nd Floor, 339 Bogyoke Aung San Street, Kyauktada Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 255118 Email address: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.dentist-myanmar.com Evergreen Dental Care No. -

REGLUGERÐ Um Þvingunaraðgerðir Varðandi Mjanmar (Búrma)

Nr. 911 26. október 2009 REGLUGERÐ um þvingunaraðgerðir varðandi Mjanmar (Búrma). 1. gr. Almenn ákvæði. Með reglugerð þessari eru sett ákvæði um þvingunaraðgerðir varðandi Mjanmar sem íslensk stjórnvöld hafa ákveðið að framfylgja á grundvelli yfirlýsingar ríkisstjórna aðildarríkja Evrópu- sambandsins og Fríverslunarsamtaka Evrópu um pólitísk skoðanaskipti, sem er hluti samningsins um Evrópska efnahagssvæðið, sbr. lög nr. 2/1993. Þvingunaraðgerðir Evrópusambandsins varðandi Mjanmar byggja á sameiginlegri afstöðu ráðs Evrópusambandsins 2006/318/CFSP frá 27. apríl 2006 ásamt síðari breytingum, uppfærslum og viðbótum: sameiginleg afstaða 2007/750/CFSP, 2008/349/CFSP, 2009/351/CFSP og 2009/615/CFSP. Gerðir Evrópusambandsins, þ.m.t. uppfærðir listar yfir aðila og hluti sem þvingunaraðgerðir beinast að eða varða, eftir því sem við á, eru birtar á vefsetri þess (http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/cfsp/sanctions/index_en.htm). Ákvæði reglugerðar nr. 119/2009 um framkvæmd alþjóðlegra þvingunaraðgerða skulu gilda um framkvæmd reglugerðar þessarar. 2. gr. Vopnasölubann. Vopnasölubann skal gilda gagnvart Mjanmar, sbr. 1. og 2. gr. 2006/318/CFSP og síðari breyt- ingar, uppfærslur og viðbætur. 3. gr. Viðskiptabann. Bannað er að selja, útvega, yfirfæra eða flytja út búnað eða tækni til fyrirtækja í Mjanmar sem stunda eftirgreindan iðnað ef sá búnaður eða tækni tengist starfsemi þeirra: a) skógarhögg og timburvinnslu, b) námuvinnslu gulls, tins, járns, kopars, volframs, silfurs, kola, blýs, mangans, nikkels og sinks, c) námuvinnslu og vinnslu eðal- eða hálfeðalsteina, þ.m.t. demanta, rúbínsteina, saffíra, jaði- steina og smaragða. Bannað er að kaupa, flytja inn eða flytja til landsins eftirgreindar vörur frá Mjanmar: a) trjáboli, timbur og timburvörur, b) gull, tin, járn, kopar, volfram, silfur, kol, blý, mangan, nikkel og sink, c) eðal- eða hálfeðalsteina, þ.m.t. -

Myanmar's Oldest and Largest Research Agency

Myanmar’s oldest and largest research agency Established in 1992 to produce Yangon Directory Has 24 branches around the country Supports government ministries with policy decision-making Provides rigorous M&E services to international and local NGOs Has assisted 300+ multinational and local companies with industrial and social research Current portfolio: Current portfolio: social and business research, social and business research, consumer, market, media, and consumer, market, media, and industrial research industrial research Proud to be an information provider and facilitator of public-private partnerships through research WHAT WE OFFER Quality Check and Data Analysis Specialized social research services for humanitarian and community-based development agencies. Our specialties: Services provided: Baseline studies Project Training Impact Monitoring Studies Pre-Testing / Piloting Program Evaluations Field Data Collection Participatory & Rapid Rural Appraisals Data Entry & Processing Feasibility Studies Reporting Social Impact Assessments Dissemination Workshops SI CLIENTS (I)NGOs UN Agencies 1) CARE 17) Supply Chain Management 2) Center for Vocational Training Services 3) GRET 18) Swiss Contact 1) UNDP 4) Help Age Int’l 19) Thadar Consortium 2) UNFPA 5) Int’l Development Enterprises 20) The Leprosy Mission Int’l 3) UNICEF 6) International Water 21) Tripartite Core Group Management Institute 4) UNOPS 22) Trocaire 7) Malteser 5) WHO 23) World Fish 8) Mercy Corps 6) FAO 24) World Vision 9) Merlin 7) ILO 25) The Asia Foundation 10) Myanmar -

A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon

A Strategic A Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) UrbanDevelopment Plan of Greater The Republic of the Union of Myanmar A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Yangon FINAL REPORT I Part-I: The Current Conditions FINAL REPORT I FINAL Part - I:The Current Conditions April 2013 Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. NJS Consultants Co., Ltd. YACHIYO Engineering Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Inc. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. 2013 April ALMEC Corporation JICA EI JR 13-132 N 0 300km 0 20km INDIA CHINA Yangon Region BANGLADESH MYANMAR LAOS Taikkyi T.S. Yangon Region Greater Yangon THAILAND Hmawbi T.S. Hlegu T.S. Htantabin T.S. Yangon City Kayan T.S. 20km 30km Twantay T.S. Thanlyin T.S. Thongwa T.S. Thilawa Port & SEZ Planning調査対象地域 Area Kyauktan T.S. Kawhmu T.S. Kungyangon T.S. 調査対象地域Greater Yangon (Yangon City and Periphery 6 Townships) ヤンゴン地域Yangon Region Planning調査対象位置図 Area ヤンゴン市Yangon City The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I The Project for The Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I < Part-I: The Current Conditions > The Final Report I consists of three parts as shown below, and this is Part-I. 1. Part-I: The Current Conditions 2. Part-II: The Master Plan 3. Part-III: Appendix TABLE OF CONTENTS Page < Part-I: The Current Conditions > CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Study Period ............................................................................................................. -

Yangon's Heritage

Yangon’s Heritage: Steps Towards Preservation Paula Z. Helfrich When I returned to live in Yangon in 2007, my sense of direction was rooted in my upbringing of the 1950s and 1960s, the bittersweet memories and epic history of those times. I knew everything and nothing – Scott Market, the English Methodist School, St. John’s, St. Mary’s Cathedral, Golden Valley, Kyaikkasan Race Course, the Union Club, Kokine Club, Park Street and the Royal Lakes, and the Rangoon Sailing Club on Victoria Lake. I was familiar with York Road, Halpin, Fraser, Prome Road, Merchant Street and a host of other Anglicized place names, but I was utterly lost in modern Yangon, until I transcribed the Strand Hotel’s antique map of downtown “Rangoon” onto a contemporary map. Finally, I had come home. More correctly, I could find homes and places I’d known, history hiding in plain sight, my favorite being the beautifully refurbished Zoological Gardens, founded in 1924. Myanmar carries the burden and blessing of one of the most romantic histories in the world, shaped by Theravada teachings, Jataka tales and Nat legends, swashbuckling Portuguese sailors and the star-crossed warrior-poet Nat Shin Aung, valiant efforts by monks, writers and students to achieve independence, the death of the Martyrs, the decades of silent national grief, the amazing new beginnings, and the age-old Buddhist principle of freedom from fear. As in most tropical cultures, there are thousands of ancient religious shrines built for the ages, but there are no ancient palaces or public halls, attributable possibly to the Buddhist view of impermanence and the devastations of World War II by three invading forces. -

Ex-Ante Evaluation (For Japanese ODA Loan) Southeast Asia Division 4, Southeast Asia and Pacific Department, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Ex-Ante Evaluation (for Japanese ODA Loan) Southeast Asia Division 4, Southeast Asia and Pacific Department, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) 1. Basic Information Country: The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Project: Yangon-Mandalay Railway Improvement Project Phase I (III) Loan Agreement: March 31, 2020 2. Background and Necessity of the Project (1)Current State and Issues of the Development of the Railway Sector in Myanmar and the Positioning of the Project The total length of the railway network in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (“Myanmar”) is 6,112 km as of 2018, and all railway lines are managed and operated by Myanmar Railways (“MR”). Most of the lines were constructed during the British colonial era, and insufficient maintenance by MR has resulted in the deterioration of railway facilities and equipment, lowering traveling speeds and causing delays, derailments, and other problems. This makes safe, consistent railway operation difficult to achieve. The Yangon-Mandalay Railway is an important railway line that connects Yangon, the country’s largest commercial city, to the capital of Naypyitaw and Mandalay, the country’s second-largest commercial city. The line is double-tracked along a roughly 620-km section, and roughly 40% of the country’s population lives along the line. Demand for the transport of people and goods is rising as the country’s economy develops, and modernizing transport facilities and equipment to improve on obsolescence is an urgent issue for improving response and services to meet further increases in demand. Under these circumstances, the Yangon-Mandalay Railway Improvement Project Phase I (“the Project”) is positioned as a high-priority project for swift implementation as part of the National Transport Master Plan formulated with assistance from JICA and approved by the Cabinet of Myanmar in December 2015. -

Flash Alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 24 Sept Evening and 25 Sept Morning Cases Friday, September 25, 2020

Flash alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 24 Sept Evening and 25 Sept Morning Cases Friday, September 25, 2020 As we reported in our previous flash alerts, 5161 new Covid-19 cases were identified yesterday evening at 20:00 Hrs and 171 new cases today at 08:00 Hrs, i.e. a total of 687 cases in 24 hours, the most massive 24-hour increase since the beginning of the pandemic. Since the beginning of the second Covid-19 wave on 16 August, 8,140 positive cases have been identified in Myanmar, i.e. 8,514 people since the beginning of the pandemic in March. Yesterday evening and today morning, 8 deaths were reported, and between this morning and this evening at 18:30, 17 more people died. In total, 172 people have died of Covid-19 since the beginning of the epidemic. At 17:00 Hrs, the MoHS released the spatial breakdown of those 687 cases: 572 in Yangon Region, 32 in Rakhine State, 30 in Ayeyarwaddy Region, 18 in Mandalay Region, 10 in Bago Region, 10 in Mon State, 8 in Sagaing Region, 3 in Thanintaryi Region, 2 in Nay Pyi Taw, 1 in Kayin State and 1 in Chin State. Since 16 August, 5,821 cases have been reported in Yangon Region. In the last 24 hours, the epidemic has surged in Thingangyun Township (+52 cases), Mayangon Township (+47 cases), Mingala Taungnyunt Township (+39 cases). Thingangyun, South and North Okkalapa, Tarmwe, Hlaing, Hlaing Thayar, Insein, Thaketa and Mingaladon Townships stand out as hotspots of the pandemic. -

DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY Office of Foreign Assets Control

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/31/2016 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2016-26124, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Office of Foreign Assets Control Unblocking of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons Resulting from the Termination of the National Emergency and Revocation of Executive Orders Related to Burma AGENCY: Office of Foreign Assets Control, Treasury. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is removing from the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN List) the names of the persons listed below whose property and interests in property had been blocked pursuant to Executive Order 13310 of July 28, 2003 (Blocking Property of the Government of Burma and Prohibiting Certain Transactions), Executive Order 13448 of October 18, 2007 (Blocking Property and Prohibiting Certain Transactions Related to Burma), Executive Order 13464 of April 30, 2008 (Blocking Property and Prohibiting Certain Transactions Related To Burma), and Executive Order 13619 of July 11, 2012 (Blocking Property of Persons Threatening the Peace, Security, or Stability Of Burma). DATES: OFAC’s actions described in this notice are effective as of October 7, 2016. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Associate Director for Global Targeting, tel.: 202/622-2420, Assistant Director for Sanctions Compliance & Evaluation, tel.: 202/622-2490, Assistant Director for Licensing, tel.: 202/622-2480, Office of Foreign Assets Control, or Chief Counsel (Foreign Assets Control), tel.: 202/622-2410 (not toll free numbers). SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Electronic and Facsimile Availability The SDN List and additional information concerning OFAC sanctions programs are available from OFAC’s website (https://www.treasury.gov/resource- center/sanctions/Pages/default.aspx). -

8Th Plenary Meeting of Sixth 47-Member State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee Concludes

Established 1914 Volume XVII, Number 74 8th Waxing of Waso 1371 ME Monday, 29 June, 2009 8th Plenary Meeting of Sixth 47-member State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee concludes YANGON, 28 June – The Eighth Plenary Meeting of Saddhama Jotikadhaja Bhaddanta Veponla Bhivamsa Agga Maha Pandita Bhaddanta Tilawka Bhivamsa the Sixth 47-member State Sangha Maha Nayaka academic affairs. gave his explanation and sought the approval. Committee continued for the second day today at At the afternoon session, members of the State Afterwards, member Sayadaws discussed tasks to Wizaya Mingala Dhamma Thabin Hall on Kaba Aye Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee discussed and be carried out in accord with the Vinaya Dhamma Hill in Mayangon Township here. decided Vinicchaya, religious and academic affairs. procedures Chapter (7), Para 56 (c) and selection of At the meeting, Agga Maha Ganthavaçaka In response to the discussions and decision about State Vinaya Sayadaws. Then the meeting concluded Bhaddanta Veponla discussed Vinicchaya affairs, the report on the activities the second period’s work successfully. Minister for Foreign Affairs U Nyan Agga Maha Saddhama Jotikadhaja Bhaddanta Sirinda progress of the Sixth State Sangha Maha Nayaka Win and wife Daw Myint Myint Soe offered a day religious affairs and Agga Maha Pandita Agga Maha Committee (First Branch), Joint-Secretary Sayadaw meal to the Sayadaws.—MNA Myitkyina in Kachin State getting prosperous Article: Myint Maung Soe; Photos: Myo Min Thein (Mayangon) Council U Tin Maung Oo told the Myanma Alin, “Our township shares the border with Sumprabum in the north, Inganyan and Waingmaw in the east, Moemauk, Bhamo and Shwegu in the south, and Mohnyin, Mogaung, Karmaing, Hpa-kant and Tanai townships in the west. -

Initial Poverty and Social Analysis

INITIAL POVERTY AND SOCIAL ANALYSIS Country: Myanmar Project Title: GMS Highway Modernization Project Lending/Financing Project Department/ SERD/SETC Modality: Division: I. POVERTY IMPACT AND SOCIAL DIMENSIONS A. Links to the National Poverty Reduction Strategy and Country Partnership Strategy The draft Country Partnership Strategy highlights regional connectivity and the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) as a priority for ADB assistance. The government has stressed as a high priority the need to improve national transport infrastructure and reduce the burden of road crashes. The project will support the government in both objectives by rehabilitating key highways, and improving the safety of the Yangon- Mandalay expressway. As such, the project has a strong, indirect poverty reduction aspect. B. Poverty Targeting General Intervention Individual or Household (TI-H) Geographic (TI-G) Non-Income MDGs (TI-M1, M2, etc.) The project will support improved access and connectivity through poor regions of Myanmar, Ayeyarwaddy and Bago, by opening up economic and social opportunities. The project will also improve the safety of the Yangon- Mandalay expressway, which will reduce vulnerability of all road users and communities. The project is classified as general intervention as the improvements will be achieved through indirect actions to address poverty and social issues. C. Poverty and Social Analysis 1. Key issues and potential beneficiaries. The main beneficiaries of the project will be the people of Ayeyarwaddy regions, rural areas of Bago and Yangon regions, users of the Yangon-Mandalay expressway, as well as passengers and shippers along the Greater Mekong East-West corridors. Ayeyarwaddy and the rural regions of Bago and Yangon targeted are among the poorest regions of Myanmar and access there is particularly vulnerable to climate impacts (floods and typhoons). -

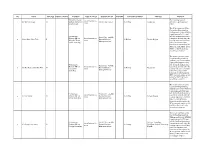

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule.