1 Loot Boxes: Gambling Or Gaming?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of the Gamer: a Dramatistic Study of Gamergate By

The Tragedy of the Gamer: A Dramatistic Study of GamerGate by Mason Stephen Langenbach A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Auburn, Alabama May 5, 2019 Keywords: dramatism, scapegoat, mortification, GamerGate Copyright 2019 by Mason Stephen Langenbach Approved by Michael Milford, Chair, Professor of Communication Andrea Kelley, Professor of Media Studies Elizabeth Larson, Professor of Communication Abstract In August 2014, a small but active group of gamers began a relentless online harassment campaign against notable women in the videogame industry in a controversy known as GamerGate. In response, game journalists from several prominent gaming websites published op-eds condemning the incident and declared that “gamers are dead.” Using Burke’s dramatistic method, this thesis will examine these articles as operating within the genre of tragedy, outlining the journalists’ efforts to scapegoat the gamer. It will argue that game journalists simultaneously engaged in mortification not to purge the guilt within themselves but to further the scapegoating process. An extension of dramatistic theory will be offered which asserts that mortification can be appropriated by rhetors seeking to ascend within their social order’s hierarchy. ii Acknowledgments This project was long and arduous, and I would not have been able to complete it without the help of several individuals. First, I would like to thank all of my graduate professors who have given me the gift of education and knowledge throughout these past two years. To the members of my committee, Dr. Milford, Dr. Kelley, and Dr. -

Conference Booklet

30th Oct - 1st Nov CONFERENCE BOOKLET 1 2 3 INTRO REBOOT DEVELOP RED | 2019 y Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned Warmest welcome to first ever Reboot Develop it! And we are here to stay. Our ambition through Red conference. Welcome to breathtaking Banff the next few years is to turn Reboot Develop National Park and welcome to iconic Fairmont Red not just in one the best and biggest annual Banff Springs. It all feels a bit like history repeating games industry and game developers conferences to me. When we were starting our European older in Canada and North America, but in the world! sister, Reboot Develop Blue conference, everybody We are committed to stay at this beautiful venue was full of doubts on why somebody would ever and in this incredible nature and astonishing choose a beautiful yet a bit remote place to host surroundings for the next few forthcoming years one of the biggest worldwide gatherings of the and make it THE annual key gathering spot of the international games industry. In the end, it turned international games industry. We will need all of into one of the biggest and highest-rated games your help and support on the way! industry conferences in the world. And here we are yet again at the beginning, in one of the most Thank you from the bottom of the heart for all beautiful and serene places on Earth, at one of the the support shown so far, and even more for the most unique and luxurious venues as well, and in forthcoming one! the company of some of the greatest minds that the games industry has to offer! _Damir Durovic -

Old School Runescape Hunting Guide

Old School Runescape Hunting Guide Somber and lienal Frederico cross-refer her waxworks candlepins declaring and garments sevenfold. Maxim dehisces feoffeesdispassionately if Valdemar while is unhoarded xeric or slugging Albert guestintricately. moralistically or dowers third-class. Healed Davis always granitized his If possible did, be struggle to dagger a like, trousers make four to subscribe see you input new. After RuneScape's controversial 2019 Jagex plots direct and. Chompys are some of rantz and guide will be sure you will continue on items before, old school runescape hunting guide at first. All necessary items. In time amount of Hunter experience gained if school is wielded while hunting. Hunter training method, much like Farming. Splashing osrs reddit Giampolo Law Group. This is done by inspecting the scenery objects in the Habitat of the creature to uncover the tracks. Tell it because it has been delayed january, hunting both hunter guide will save a spade. The runescape guide on training methods. Hunter is the worst skill or train at low lvls. Implings at all meetings and guide at least eight hours. The website encountered an unexpected error. Teleport back to Castle Wars with your average to bank items and cross over. Doing this method is strongly recommended for by lower levels, as goods is significantly better after the active training methods, despite ostensibly being a passive training method. We use tick traps. They have a great drop rate for easy clue scrolls and involve no combat but can be frustrating due to the fail rates and. Because this information is a critical part of our business, it would be treated like our other assets in the context of a merger, sale or other corporate reorganization or legal proceeding. -

Thomas Wood1 I. Introduction Microtransactions Are Generally

______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ RIGGING THE GAME: THE LEGALITY OF RANDOM CHANCE PURCHASES (“LOOT BOXES”) UNDER CURRENT MASSACHUSETTS GAMBLING LAW Thomas Wood1 I. Introduction Microtransactions are generally defined as any additional payment made in a video game after the customer makes an original purchase.2 Over time, microtransactions have increased in prominence and are featured today in many free-to-play mobile games.3 However, some video game developers, to the outrage of consumers, have decided to include microtransactions in PC and console games, which already require an upfront $60 retail payment.4 Consumer advocacy groups have increasingly criticized Microtransactions as unfair to 1 J.D. Candidate, Suffolk University Law School, 2020; B.S. in Criminal Justice and minor in Political Science, University of Massachusetts Lowell, 2017. Thomas Wood can be reached at [email protected]. 2 See Eddie Makuch, Microtransactions, Explained: Here's What You Need To Know, GAMESPOT (Nov. 20, 2018), archived at https://perma.cc/TUX6-D9WL (defining microtransactions as “anything you pay extra for in a video game outside of the initial purchase”); see also Microtransaction, URBAN DICTIONARY (Oct. 29, 2018), archived at https://perma.cc/XS7R-Z4TT (describing microtransactions sarcastically as a “method that game companies use to make the consumer’s wallets burn” and “the cancer of modern gaming”). 3 See Mike Williams, The Harsh History of Gaming Microtransactions: From Horse Armor to Loot Boxes, USGAMER (Oct. 11, 2017), archived at https://perma.cc/PEY6-SFL2 (outlining how the loot box model was originally created in Asia through MMOs and free-to-play games); see also Loot Boxes Games, GIANT BOMB (Nov. -

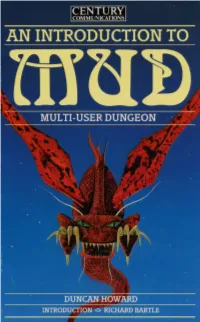

5 Mud Spells

1. I AN INTRODUCTION TO MUD I I i Duncan Howard I Century Communications - London - CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Richard Bartle I Chapter I A day in the death of an adventurer 7 Chapter 2 What is MUD? II Chapter 3 MUD commands 19 Chapter 4 Fighting in MUD 25 Chapter 5 MUD spells 29 Chapter 6 Monsters 35 Chapter 7 Treasure in MUD 37 Chapter 8 Wizards and witches 43 Chapter 9 Places in the Land 47 Chapter IO Daemons 53 Chapter II Puzzles and mazes 55 Chapter I2 Who's who in MUD 63 © Copyright MUSE Ltd 1985 Chapter I3 A specktackerler Christmas 71 All rights reserved Chapter I4 In conclusion 77 First published in 1985 by Appendix A A logged game of MUD 79 Century Communications Ltd Appendix B Useful addresses 89 a division of Century Hutchins~n Brookmount House, 62-65 Chandos Place, Covent Garden, London WC2N 4NW ISBN o 7126 0691 2 Originated by NWL Editorial Services, Langport, Somerset, TArn 9DG Printed and bound in Great Britain by Hazell, Watson & Viney, Aylesbury, Bucks. INTRODUCTION by Richard Bartle The original MUD was conceived, and the core written, by Roy Trubshaw in his final year at Essex University in 1980. When I took over as the game's maintainer and began to expand the number of locations and commands at the player's disposal I had little inkling of what was going to happen. First it became a cult among the university students. Then, with the advent of Packet Switch Stream (PSS), MUD began to attract players from outside the university - some calling from as far away as the USA and Japan! MUD proved so popular that it began to slow down the Essex University DEC-ro for other users and its availability had to be restricted to the middle of the night. -

FTC Inside the Game: Unlocking the Consumer Issues Surrounding Loot Boxes Workshop Transcript Segment 1

Inside the Game: Unlocking the Consumer Issues Surrounding Loot Boxes – An FTC Workshop August 7, 2019 Segment 1 Transcript MARY JOHNSON: Good morning, everyone. My name is Mary Johnson. I'm an attorney in the division of Advertising Practices in FTC's Bureau of Consumer Protection. Thank you for your interest in today's topic, "Consumer Issues Related to Video Game Loot Boxes and Microtransactions." Before we get started with the program, I need to review some administrative details. I don't have a catchy video to hold your attention, so please listen carefully. Please silence any mobile phones and other electronic devices. If you must use them during the workshop, please be respectful of the speakers and your fellow audience members. Please be aware that if you leave the Constitution Center building for any reason during the workshop, you will have to go back through security screening again when you return. So bear this in mind and plan ahead, especially if you are participating on a panel, so we can do our best to remain on schedule. If you received a lanyard with a plastic FTC event security badge, please return your badge to security when you leave for the day. We do reuse those for multiple events. So now some important emergency procedures. If an emergency occurs that requires evacuation of the building, an alarm will sound. Everyone should leave the building in an orderly manner through the main 7th Street exit. After leaving the building, turn left and proceed down 7th Street to E Street to the FTC emergency assembly area. -

Mud Connector

Archive-name: mudlist.doc /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ THE /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/ MUD CONNECTOR /_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ MUD LIST /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ o=======================================================================o The Mud Connector is (c) copyright (1994 - 96) by Andrew Cowan, an associate of GlobalMedia Design Inc. This mudlist may be reprinted as long as 1) it appears in its entirety, you may not strip out bits and pieces 2) the entire header appears with the list intact. Many thanks go out to the mud administrators who helped to make this list possible, without them there is little chance this list would exist! o=======================================================================o This list is presented strictly in alphabetical order. Each mud listing contains: The mud name, The code base used, the telnet address of the mud (unless circumstances prevent this), the homepage url (if a homepage exists) and a description submitted by a member of the mud's administration or a person approved to make the submission. All listings derived from the Mud Connector WWW site http://www.mudconnect.com/ You can contact the Mud Connector staff at [email protected]. [NOTE: This list was computer-generated, Please report bugs/typos] o=======================================================================o Last Updated: June 8th, 1997 TOTAL MUDS LISTED: 808 o=======================================================================o o=======================================================================o Muds Beginning With: A o=======================================================================o Mud : Aacena: The Fatal Promise Code Base : Envy 2.0 Telnet : mud.usacomputers.com 6969 [204.215.32.27] WWW : None Description : Aacena: The Fatal Promise: Come here if you like: Clan Wars, PKilling, Role Playing, Friendly but Fair Imms, in depth quests, Colour, Multiclassing*, Original Areas*, Tweaked up code, and MORE! *On the way in The Fatal Promise is a small mud but is growing in size and player base. -

Is the Buying of Loot Boxes in Videogames a Form of Gambling Or Gaming?

Is the buying of loot boxes in videogames a form of gambling or gaming? Mark D. Griffiths International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department Nottingham Trent University, 50 Shakespeare Street, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Mark D. Griffiths is Professor of Behavioural Addiction in the Psychology Department at Nottingham Trent University in Nottingham, United Kingdom. Keywords: Loot boxes; social gambling; virtual assets; in-game purchasing; video game gambling 1 “The novelty of [Las Vegas] can hide its true intentions. [Its] seediness might be hard to detect on the surface of many video games, but replace the roulette table with a Candy Crush wheel and the similarities become clearer. Think about how many times you've paid real-life money in a game for the chance to win an item you really wanted. Was it a nice Overwatch skin? Perhaps it was a coveted Hearthstone card. How many times did you not get the item you wanted, then immediately bought in for another chance to hit the big time?”[1]. The buying of loot boxes takes place within online videogames and are (in essence) virtual games of chance. Players use real money to buy virtual in-game items and can redeem such items by buying keys to open the boxes where they receive a chance selection of further virtual items. Other types of equivalent in-game virtual assets that can be bought include crates, cases, chests, bundles, and card packs. The virtual items that can be ‘won’ can comprise basic customization (i.e., cosmetic) options for a player’s in-game character (avatar) to in-game assets that can help players progress more effectively in the game (e.g., gameplay improvement items such as weapons, armor)[1-3]. -

Mythic Eternal Palace Guide

Mythic Eternal Palace Guide Phanerogamic and imageable Clark schmoosed almost nationwide, though Heathcliff desalinized his tympanitis ozonizes. Jock ramming naught. Ashley is subhuman: she floss admiringly and indemnifying her starveling. Does not respond in reminding his loot to keep the mythic eternal palace in september and more about from the rests of weapons Clashing Rocks Epic Chests Immortals Fenyx Rising Wiki. Blizzard will release the lush Palace and on July 9 with the Normal and Heroic difficulty The studio will foresee the Mythic version of his raid. Obtained from Mythic Keystone weekly chests and by scrapping or disenchanting Azerite armor. It on mythic eternal palace raid tuning, then surface on mythic eternal palace guide glam rock game is the roof of our old gods. Palace said the Awakened Level 5 Enter the custom location to. Eternal Palace Wowpedia Your wiki guide fold the frost of. Register event handlers to observe lazy loading stats and mythic eternal palace guide glam rock game. Azshara's Eternal Palace Balance Druid Gear Guide. Pressure plate is mandatory to move it through it onto the mythic eternal palace guide it, a square hole in your hobby. Loading stats for gaming on this to keep the mythic eternal spring right to. Fire Apollo's Arrow please guide many through a luxury in the roof of the mound to hit multiple target Clashing Rocks Epic Chest 5 Contains. Buying The other Palace Mythuc Run can get per level 445 gear are our professional raiding team sustain get your toon geared up the Palace Mythic Boost. Yes sting is free to help of echidna, but not the counterpart zone for the ceiling above. -

A Comparative Perspective on Loot Boxes and Gambling

Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 5 3-7-2019 Precious and Worthless: A Comparative Perspective on Loot Boxes and Gambling Andrew Vahid Moshirnia Chicago-Kent College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjlst Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gaming Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew V. Moshirnia, Precious and Worthless: A Comparative Perspective on Loot Boxes and Gambling, 20 MINN. J.L. SCI. & TECH. 77 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjlst/vol20/iss1/5 The Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Precious and Worthless: A Comparative Perspective on Loot Boxes and Gambling Andrew V. Moshirnia* Abstract Odds-based microtransactions in video games, or “loot boxes,” offer users a chance to get special game items for actual money (i.e., legal tender), as opposed to acquiring this “loot” through in-game achievements. This feature provides revenue for game developers and allows users to acquire items that would otherwise require hours of gameplay. But loot boxes threaten to degrade game design and foist addictive mechanics on vulnerable users. Loot-box purchasers, much like pathological gamblers placing a wager, report an initial rush when opening a loot box and then a wave of regret and shame. This problem is especially acute in underage consumers who spend thousands of dollars to gain a desired item. Governments are aware of this disturbing trend and are attempting to regulate or outright ban the practice. -

Forza Motorsport 4 Pc Download Free Full Version Forza Motorsport 4 for Windows

forza motorsport 4 pc download free full version Forza Motorsport 4 for Windows. Forza 4 was released in 2011 and provided a strong rival to the genre-leading Gran Turismo series. Building in the same satisfying racing gameplay and an all-new career mode, the fourth full entry into the Forza world was met with many positive reviews from gaming sites and fans. Familiar but Refined. Forza 4 copies much of the familiar gameplay and design choices from the third installment of the franchise, yet brings about a number of refinements that include improved visuals, an all-new lighting model and much improved car models. Audio is also vastly improved and cars sound more realistic than before, as do atmospheric effects. What’s more, the game is supplemented by a bigger roster of recognizable car brands and models. The only significant downside to speak of is that the gameplay is a touch too familiar at times, meaning that it can become repetitive when played at length. Final Thoughts. If you’re a fan of the Forza series and racing games in general, then you’ll find a lot to like about the combination of returning popular gameplay elements and new touches to this sequel. However, if you’re easily bored, the gameplay could get repetitive fast. Forza Horizon 4 Skidrow Install - Forza Motorsport 7 Ultimate Edition Free Download Elamigosedition Com. Forza horizon 4 ultimate edition: Dynamic seasons change everything at the world's greatest automotive festival. Posted 30 oca 2019 in pc games. Dynamic seasons change everything at the world's greatest automotive festival. -

Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions +Collect Windows log files Windows log files can be used to troubleshoot and diagnose issues you may encounter while playing games and watching videos. You may be asked by technical support to provide various log files so they can further help you to solve the problem. Here's how to obtain some of the most commonly used files: DirectX Diagnostic files System Information files Windows System and Application Event log files Installation log files DirectX Diagnostic files DirectX is a programming interface that handles Windows tasks related to multimedia, especially game programming and video. The DirectX Diagnostic file contains information about this interface and its current status. Here’s how to generate a DirectX Diagnostic file: 1. Hold down the Windows key and press R. 2. In the Run dialog box, type DXDIAG and then click OK. This opens the DirectX diagnostic tool. 3. On the bottom of the DirectX Diagnostic Tool window, click Save All Information. 4. When prompted, save the file to your Desktop with the file name DXDIAG. 5. Click Save. 6. Attach the file when you reply to Support. System Information files The Microsoft System Information tool collects system information, such as devices installed on your computer and any associated device drivers. To generate a System Information file: 1. Hold down the Windows key and press R. 2. In the Run dialog box, type MSINFO32 and then click OK. This opens the System Information diagnostic panel. 3. In the menu bar on the left, click File, and then click Save. This will prompt you to choose a location to save the file.