A Brief Introduction to the Saga of the Labor Movement for Emerging Militants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Labor Merchant

DAVE BECK: Labor Merchant By Eric Hass Published Online by Socialist Labor Party of America www.slp.org November 2006 Dave Beck: Labor Merchant The Case History of a Labor Leader By Eric Hass PUBLISHING HISTORY FIRST PRINTED EDITION ..................... August 19, 1955 SECOND PRINTED EDITION ................... April 17, 1957 ONLINE EDITION .................................... November 2006 NEW YORK LABOR NEWS P.O. BOX 218 MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA 94042-0218 http://www.slp.org/nyln.htm Dave Beck: Labor Merchant The Case History of a Labor Leader By Eric Hass ERIC HASS (1905–1980) 1. A Labor Merchandising Concern “Labor organization is a business; like any other business, it is run primarily to produce a living for those who make it their vocation.” —Wall Street Journal, March 9, 1939. To start a business, the first thing you must have is capital. If it is a factory, you need capital for machinery, plant space and raw material. If it is a mine, you need capital for mining equipment. If it is a store, you need capital for merchandise and rent. And, if it is any of these, or any other kind of business you can name—except one—you must have capital to lay out for labor as well as for other things. The lone exception is a “union” business. A labor leader can go into the “union”—labor-merchandising—business with very little. He gets his stock-in- trade—workingmen and workingwomen, the human embodiment of labor power—free, gratis and for nothing. If things go right, and enough employers are lined up and contracts signed, thereby giving the labor leader control of jobs, the money rolls in. -

Walkouts Teach U.S. Labor a New Grammar for Struggle

Walkouts teach U.S. labor a new grammar for struggle This article will appear in the Summer 2018 issue of New Politics. Like the Arab Spring, the U.S. “education Spring,” was an explosive wave of protests. State-wide teacher walkouts seemed to arise out of nowhere, organized in Facebook groups, with demands for increased school funding and political voice for teachers. Though the walkouts confounded national media outlets, which had little idea how to explain or report on the movements, for parent and teacher activists who have been organizing against reforms in public education in the past four decades, the protests were both unexpected and understandable. What was surprising was their breadth of support (state-wide), their organizing strategy (Facebook), and their breathtakingly rapid spread. For most of the far-Right, the West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and North Carolina walkouts showed greedy public employees exploiting their job security to get pay and benefits better than hard-working taxpayers have. However, teachers won wide popular support, even from Republicans, forcing the media-savvier elements of the Right to alter their tone. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) posted a blog with a sympathetic tone pushing the same stance. “While teachers are justly frustrated by take-home pay, their total compensation is typically a lot higher than many teachers realize. That’s because teacher retirement and health-care systems are much more expensive than those of the taxpayers who pay for them — whether those taxpayers work in the private or public sector.” Shedding crocodile teachers for teachers who are underpaid and retirees without adequate pensions, AEI rejects the idea more school funding would help. -

Working Class

A NEW WORKING CLASS Students for a Democratic Society and the United Auto Workers in the Sixties Amanda L. Bullock A NEW WORKING CLASS: Students for a Democratic Society and the United Auto Workers in the Sixties by Amanda Leigh Bullock A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelors of the Arts with Honors Department of History University of Michigan March 27, 2006 Advised by: Professor Matthew D. Lassiter © 2006 Amanda Leigh Bullock TABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS II INTRODUCTION: STUDENTS, MIDDLE AMERICANS, AND CLASS CONSCIOUSNESS 1 DEMOCRATIC DISSENT 4 HISTORIOGRAPHY 7 CHAPTER ONE: NATURAL ALLIES? 15 THE LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 17 THE PORT HURON STATEMENT: “AN AGENDA FOR A GENERATION” 19 THE “OLD” LEFT 23 THE NEW LEFT: THE NATURAL ALLIANCE OF THE LABOR AND CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENTS? 27 STUDENTS AND LABOR 30 AUTONOMY 36 CHAPTER TWO: THE WAR ON POVERTY AND THE NEW INSURGENCY 42 THE CITIZENS’ CRUSADE AGAINST POVERTY 46 INSURGENCY TO THE WAR ON POVERTY 53 FROM FAYETTE COUNTY TO THE GHETTO 56 “AN INTERRACIAL MOVEMENT OF THE POOR” 60 THE FAILURE OF ERAP 67 FAILURE: THE CAMPUS VERSUS THE COMMUNITY 67 FAILURE: THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF AN EXPERIMENTAL PROJECT 71 FAILURE: THE ESCALATION OF THE VIETNAM WAR 73 THE LEGACY OF THE ECONOMIC RESEARCH AND ACTION PROJECT 75 CHAPTER THREE: IMPLOSION 79 THE ANTI-WAR MOVEMENT: SDS OUTGROWS ITSELF 81 STUDENTS FOR A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY’S 1968 WORK-IN 90 THE 1968 DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION 94 THE DEATH OF SDS 101 THE TROUBLED AMERICANS 106 PRIMARY SOURCES 113 BIBLIOGRAPHY 115 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I am indebted to Professor Matt Lassiter, without whose guidance and patience I never could have accomplished this. -

Seattle AFL Convention Delegate Scores Beck Gangsterism

Seattle AFL Convention Delegate Scores Beck Gangsterism Read This Issue for FARMERS! Oregon Election The Voice of Action ~ News VOICE OF ACTION Is Your Paper 2 SEATTLE, WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, 12, FIVECENTS VOLUME TELEPHONE MAIN 1525 OCTOBER 1934 OFFICERREPORTSANTI-WARMOVEINARMY OFFICER REPORTS ANTI-WAR MOVE IN ARMY The Central Labor Correll Opens League Men FRONT Demands A.F.L - - ’Uniformed_S?pok_esmen BY Council Balks Campaign Catch Union - for LINE ALAN MAX '])allas~ Support General Strike AtGreen Edict Oregon Gov. Label Forger Chi. Congress Sensation SEATTLE, Oct. 10-The AF ‘ of L. Central Council here last SEATTLE, Oct. 10 Forgery - Continental . week unanimously refused to SALEM, Ore, Oet. 11-—-Runn- and fraudulent use of the Allied Committee on Rank and File, Regular Flour, Cereal Unionist act on a communication from ing on an independent ticket, en- Trades union printing label by a Anti-War Congress Is Guardsman Says Men To g president, . - William Green AFL dorsed by the Communist Party seab printing shop was unearthed Technocracy Conventions Are Introduces Militant calling for expulsion of all and the United Farmers League, Largest In U. §. Fight Shooting of ! carry- last week when Bill McHale and ‘ » - ~ - Communists and those which he is State Organizer, of Benditi, of the Printers’ ing on Communist activity Harry Correll, of Salem, opened William Technoeracy | Resolutions League (AFL). History ‘ Strikers Howard Scott is Contras ted or propaganda. his campaign in the Italian Fed- Label Promotion openly } forger, a Japanese, K. Sa- fascist. But what about bureaucratie command eration hall, 4th and Madison The the Continental Committee on By of Action Special By Voice of Action The ito, manager of the G. -

David Beck CV

David Beck Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin- Stout School of Art and Design College of Arts, Communications, Humanities and Social Sciences Office: 235 Applied Arts Phone: 715-232-1287 Email: [email protected] Personal website: www.davebeck.org Brief Biography Dave Beck is a practicing 3D digital and new media artist, living in Wisconsin. He is the recipient of the 2010 International Science & Engineering Visualization Challenge Award, given by the National Science Foundation. Beck's artwork has been featured in publications such as the New York Times, Sculpture Magazine, National Geographic, the journal Science, and the book GameScenes: Art in the Age of Videogames. Research Interests: Dave is currently working on an art video game, titled Tombeaux. This interactive experience investigates the convergence between cultures and the environment across a few hundred years of midwestern American history. Visit the official game site at: http://www.tombeauxgame.com/ Education o MFA Sculpture & Extended Media University of Wisconsin- Madison Madison, WI, United States, 2007 o MA Studio Art University of Wisconsin- Madison Madison, WI, United States, 2006 o BA Studio Arts & Ancient Studies St. Olaf College 2002 Work Experience Academic - Post-Secondary ▪ University of Wisconsin- Stout Associate Professor 2011 - ▪ Clarkson University Assistant Professor of Digital Art & Sciences 2007 - 2011 ▪ University of Wisconsin- Madison, Art Department Instructor of 3D Design 2004 - 2007 Artistic and Professional Performances and Exhibits Art - Exhibition, One-Person o Beck, D. (Present) Tombeaux. Phipps Center for the Arts. Hudson, WI, United States. o Beck, D. (Present) Northern Lights. 50 ft. Projection on MCAD Building. Minneapolis, MN, United States. o Beck, D. -

03.2009 174-TR-Histo

TEAMSTERS LOCAL 174 NON PROFIT ORG 14675 Interurban Avenue South US POSTAGE Tukwila, Washington 98168-4614 PAID SEATTLE, WA PERMIT NO. 1104 THE LOCAL 174 Official Publication of Teamsters Local 174 • Tukwila, Washington • Volume 3, Number 1 • January-March 2009 100TH BIRTHDAY Local 174 signed its Charter on February 19, 1909 as an affiliate of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Secretary-Treasurer’s Message HAPPY 100TH BIRTHDAY TO ALL LOCAL 174 MEMBERS AND THEIR FAMILIES Sisters and Brothers: As we look back and celebrate the first 100 years of our great Local Union, we must take the opportunity to acknow- ledge and congratulate those who came before us. Their struggles provided many of the ben- efits we have today. Much of what we take for granted on a daily basis was secured through real blood, sweat and tears. We often overlook the years of struggle our forefathers endured to lay the foundation for many of the best contracts in the Country. Seattle was at the forefront of the Labor Movement when Teamsters Lo- cal 174 was chartered one hundred years ago. It was during those early years when our background of mili- RICK HICKS tancy was born and we have never forgotten our roots. The Local’s members have always been up to the task and we have only gotten stronger as time passes on. Teamsters Local 174 has not only witnessed, but partici- pated in many of the Labor victories over the last Century. Without the sacrifices made by our predecessors, we would still be working seven days a week and twenty hours a day. -

Reclaiming Syndicalism: from Spain to South Africa to Global Labour Today

Global Issues Reclaiming Syndicalism: From Spain to South Africa to global labour today Lucien van der Walt, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa Union politics remain central to the new century. It remains central because of the ongoing importance of unions as mass movements, internationally, and because unions, like other popular movements, are confronted with the very real challenge of articulating an alternative, transformative vision. There is much to be learned from the historic and current tradition of anarcho- and revolutionary syndicalism. This is a tradition with a surprisingly substantial and impressive history, including in the former colonial world; a tradition that envisages anti-bureaucratic and bottom-up trade unions as key means of educating and mobilising workers, and of championing the economic, social and political struggles of the broad working class, independent of parliamentary politics and party tutelage; and that aims, ultimately, at transforming society through union-led workplace occupations that will institute self-management and participatory economic planning, abolishing markets, hierarchies and states. This contribution seeks, firstly, to contribute to the recovery of the historical memory of the working class by drawing attention to its multiple traditions and rich history; secondly, to make a contribution to current debates on the struggles, direction and options for the working class movement (including unions) in a period of flux in which the fixed patterns of the last forty years are slowly melting away; thirdly, it argues that many current union approaches – among them, business unionism, social movement unionism, and political unionism – have substantial failings and limitations; and finally, it points to the need for labour studies and industrial sociology to pay greater attention to labour traditions besides business unionism, social movement unionism, and political unionism. -

Sources for the Working Longshoreman 44

43. George Ginnis Interview. Sources For The Working Longshoreman 44. The term "13 Men" originated in Southern California in 1950. By 1958. "B Men" had become standard usage everywhere on the Pacific Coast. replacing the term "permit men" Interviews in the Pacific Northwest. See Hartman. p. 36. 45. W. G. Rowland, Trade Analysis. in Port and City 01 Tacoma 1921. Tacoma Longshoremen Interviewed: 46. Chester Barker Interview. Initiation Year Initiation Year 47. Annual Port 0/ Tacoma Report jin 1930. 48. Reichl Files. Lyle Ames 1929 George Ginnis 1957 49. Shaun Maloney Interview. Harold R. Anderson 1950 Philip M. Lelli 1957 50. Carl Weber Interview. Tom Anderson 1980 George Liefson 1919 51. Port 0/ Tacoma Annual Reports. /953-/972. Nels Arneson 1929 Paul Lindberg 1930 52. Purt ()( Tacoma Annual Report jin /1)65. Port of Tacoma Annual Report /or /1)74. Al Arnestad 1919 Richard Marzano 1973 53. George Ginnis Interview. Chester Barker 1929 George Mitchell 1918 54. Carl Engels Interview. Lee Barker 1918 John Now 1916 55. Philip I.elli Interview. Lelli served as president of Loeal23 from 1966-1967, 1971-1975, Wardell Canada 1954 Vic Olsen 1926 and 1979-1984. He is currently vice president of the local. Les Clemensen 1929 Frank E. Reichl 1940 56. TNT, July 2, 1971. C C Doyle 1928 Lee L. Reichl 1940 57. Ibid., July 6, 1971. Carl Engels 58. Dai~v Shipping News. July 9, 1971. 1950 Jack Tanner 1942 59. TNT August 28, 1971. Nicholas Engels 1945 Morris Thorsen 1925 60. PI, October 7. 1971. Joseph E. Faker 1965 T. A. -

Convention History Booklet

A Gathering of Teamsters: A Look at the First Five Decades of Convention History ISBn 978-1-935833-00-0 In Celebration of The International Brotherhood of Teamsters 30th Convention | June 2021 Cover photo: Delegates at the1910 Convention A Gathering of Teamsters: A Look at the First Five Decades of Convention History In Celebration of The International Brotherhood of Teamsters 30th Convention | June 2021 James P. Hoffa Ken Hall General President General Secretary-Treasurer Convention Call letter 1920 4 Teamsters Convention 2021 A CALL TO CONVENTION he Call to the Convention has always generated excitement – and rightly so. Not only is it an opportunity to see friends and fellow delegates from around the country, it’s a chance to discuss Timportant issues facing the Union and labor in general. The Convention’s most anticipated event is the nomination of candidates for International office as part of the five-year election cycle. The constitution of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters makes the role of the Convention very clear. It states that: “The International Convention shall be the supreme governing authority of the Inter- national Union and shall have the plenary power to regulate and direct the policies, affairs, and organi- zation of the International Union.” In the early days, the union’s Conventions and elections were held every year. It was thought that, as a young Union founded in 1903, leaders and delegates needed to meet on a frequent basis to guide the union’s path and build a strong foundation. By 1908, the leadership felt the union was steady enough on its feet to meet every two years instead of annually. -

32AB Tape 1 (45)

- #32AB 1. Tape 1 (45) - Side 1 Q: Maybe we can start by you telling me where and when you were born, how you came to Seattle. A: February 5, 1896, in Warsaw, Indiana. I came to Seattle in 1902, when I was six years old. My folks () in Spokane, until I came to the University in 1915. Q: What did your folks do? A: My father and mother were both lawyers. My mother was the first woman to take the bar in Indiana. That was a remarkable exception. It wasn't schooling that they required, it's just take an examination, and my father, being a lawyer, helped her do it, and so on, and she never practiced law, as a matter of fact, but anyway, she had that distinction. Being the first woman in the bar in Indiana, and she became quite a politician, as a matter of fact. She was the first national committee woman, democratic committee woman, of this state. I got my political persuasion from the fact that my mother was very dominant in politics. She toured the state with Franklin D. Roosevelt when he was running for Vice President with Jimmy Cox in 1920. And on a train tour, to Washington. So, as I say, I'm a democrat, a moderate democrat, not a wild-eyed liberal. But a moderate democrate, Jimmy Carter's ( ) althouth I had a ( ) and I voted for McGovern. But I did that because I wanted to vote against Nixon. So there you get a little idea. Q: SO family politics was discussed alot when you were growing up? A: Oh, yes. -

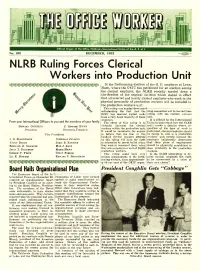

Workers Into Production Unit in the Forthcoming Election of the G

[!) iii t rrrrrrrcr-rmi " 1' r 1""{;11/: HI Official Organ of the Office F.mployes International Union of the A. F. of L. No. 108 DEC1EMBER, 1953 NLRB Ruling Forces Clerical Workers into Production Unit In the forthcoming election of the G. E. employes at Lynn, Mass., where the OEIU has petitioned for an election among the clerical employes, the NLRB recently handed down a clarification of the original decision which stated in effect that all salaried and hourly clerical employes who work in the physical proximity of production workers will be included in the production workers unit. This ruling was handed down not- withstanding the fact that the izing committee will be barred from OEIU has received signed cards voting with the clerical workers from a very large majority of these unit. employes. It is difficult for the International From your International Officers to you and the members of your family The effect of this ruling is to Union to understand how the NLRB HOWARD COUGHLIN J. HOWARD HICKS virtually imprison the clerical could render a decision where, re- President Secretary-Treasurer workers within the production unit. gardless of the type of work is It would be unrealistic for anyone performed, clerical employes should Vice Presidents to believe that the four or five be forced to vote in a uroduction hundred clerical workers affected workers' unit merely because the J. 0. BLOODWORTH NICHOLAS JULIANO by this ruling will have the right employer unilaterally determines EMILY BURNS JOHN B. KINNICK to determine by secret ballot whom that their place of employment BERNARD H. -

Why Not a General Strike David L

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 20 Article 5 Issue 2 Symposium on the American Worker 1-1-2012 Why Not A General Strike David L. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation David L. Gregory, Why Not A General Strike, 20 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 621 (2006). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol20/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHY NOT A GENERAL STRIKE? DAVID L. GREGORY* When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose You're invisible now .... 1 -Bob Dylan INTRODUCTION Why not a general strike? Why not? This essay deliberately goes outside, indeed, shatters, the proverbial box. On the face of things, a general strike seems hopelessly and stupidly naive, idealistic, utopian, romantic, nihil- istic, impossible-insane. Of course, there are a plethora of pru- dential reasons to never call for, let alone engage in, a general strike. Most immediately, most workers, unionized2 or not, in the private and public sectors,' who engaged in a general strike, would be vulnerable to discharge. In an era of record personal bankruptcies virtually every year,4 most workers struggle to live paycheck to paycheck and save nothing. In the daily reality of most workers, labor militancy has been most ruthlessly sup- * Professor of Law, St.