Communication Accommodation Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructional Communication 8 the Emergence of a Field

Instructional Communication 8 The Emergence of a Field Scott A. Myers ince its inception, the field of instructional communication has Senjoyed a healthy existence. Unlike its related subareas of communi- cation education and developmental communication (Friedrich, 1989), instructional communication is considered to be a unique area of study rooted in the tripartite field of research conducted among educational psychology, pedagogy, and communication studies scholars (Mottet & Beebe, 2006). This tripartite field focuses on the learner (i.e., how students learn affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively), the instructor (i.e., the skills and strategies necessary for effective instruction), and the meaning exchanged in the verbal, nonverbal, and mediated messages between and among instructors and students. As such, the study of instructional com- munication centers on the study of the communicative factors in the teaching-learning process that occur across grade levels (e.g., K–12, post- secondary), instructional settings (e.g., the classroom, the organization), and subject matter (Friedrich, 1989; Staton, 1989). Although some debate exists as to the events that precipitated the emer- gence of instructional communication as a field of study (Rubin & Feezel, 1986; Sprague, 1992), McCroskey and McCroskey (2006) posited that the establishment of instructional communication as a legitimate area of scholarship originated in 1972, when the governing board of the Inter- national Communication Association created the Instructional Communi- cation Division. The purpose of the Division was to “focus attention on the role of communication in all teaching and training contexts, not just the teaching of communication” (p. 35), and provided instructional communication researchers with the opportunity to showcase their scholarship at the Association’s annual convention and to publish their research in Communication Yearbook, a yearly periodical sponsored by the Association. -

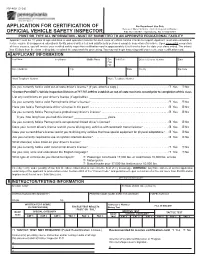

Penndot Form MV-409

MV-409 (3-18) www.dmv.pa.gov APPLICATION FOR CERTIFICATION OF For Department Use Only BureauP.O. Box of Motor 68697 Vehicles Harrisburg, • Vehicle PAInspection 17106-8697 Division OFFICIAL VEHICLE SAFETY INSPECTOR • PRINT OR TYPE ALL INFORMATION - MUST BE SUBMITTED TO AN APPROVED EDUCATIONAL FACILITY Applicant must be 18 years of age and have a valid operator’s license for each class of vehicle he/she intends to inspect. Applicant must also complete a lecture course at an approved educational facility, pass a written test and satisfactorily perform a complete inspection of a vehicle. upon successful completion of these courses, you will receive your certified safety inspection certification card in approximately 6 to 8 weeks from the date your class ended. The school has 35 days from the class ending date to submit the paperwork for processing. You may not begin inspecting until you receive your certification card. A APPLICANT INFORMATION Last Name First Name Middle Name Sex birth Date Driver’s License Number State r M r F Street Address City State County Zip Code Work Telephone Number Home Telephone Number Do you currently hold a valid out-of-state driver’s license? (If yes, attach a copy.) . r Yes r No *Contact PennDOT’s Vehicle Inspection Division at 717-787-2895 to establish an out-of-state mechanic record prior to completion of this class. List any restrictions on your driver’s license (if applicable): ______________________________________________________________ Do you currently hold a valid Pennsylvania driver’s license? . r Yes r No Have you held a Pennsylvania driver’s license in the past? . -

Social Scientific Theories for Media and Communication JMC:6210:0001/ 019:231:001 Spring 2014

Social Scientific Theories for Media and Communication JMC:6210:0001/ 019:231:001 Spring 2014 Professor: Sujatha Sosale Room: E254 AJB Office: W331 AJB Time: M 11:30-2:15 Phone: 319-335-0663 Office hours: Wed. 11:30 – 2:30 E-mail: [email protected] and by appointment Course description and objectives This course explores the ways in which media impact society and how individuals relate to the media by examining social scientific-based theories that relate to media effects, learning, and public opinion. Discussion includes the elements necessary for theory development from a social science perspective, plus historical and current contexts for understanding the major theories of the field. The objectives of this course are: • To learn and critique a variety of social science-based theories • To review mass communication literature in terms of its theoretical relevance • To study the process of theory building Textbook: Bryant, J. & Oliver M.B. (2009). Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. 3rd Ed. New York: Routledge. [Available at the University Bookstore] Additional readings will be posted on the course ICON. Teaching Policies & Resources — CLAS Syllabus Insert (instructor additions in this font) Administrative Home The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences is the administrative home of this course and governs matters such as the add/drop deadlines, the second-grade-only option, and other related issues. Different colleges may have different policies. Questions may be addressed to 120 Schaeffer Hall, or see the CLAS Academic Policies Handbook at http://clas.uiowa.edu/students/handbook. Electronic Communication University policy specifies that students are responsible for all official correspondences sent to their University of Iowa e-mail address (@uiowa.edu). -

LS-CAT: a Large-Scale CUDA Autotuning Dataset

LS-CAT: A Large-Scale CUDA AutoTuning Dataset Lars Bjertnes, Jacob O. Tørring, Anne C. Elster Department of Computer Science Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Trondheim, Norway [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—The effectiveness of Machine Learning (ML) meth- However, these methods are still reliant on compiling and ods depend on access to large suitable datasets. In this article, executing the program to do gradual adjustments, which still we present how we build the LS-CAT (Large-Scale CUDA takes a lot of time. A better alternative would be to have an AutoTuning) dataset sourced from GitHub for the purpose of training NLP-based ML models. Our dataset includes 19 683 autotuner that can find good parameters without compiling or CUDA kernels focused on linear algebra. In addition to the executing the program. CUDA codes, our LS-CAT dataset contains 5 028 536 associated A dataset consisting of the results for each legal combina- runtimes, with different combinations of kernels, block sizes and tion of hardware systems, and all other information that can matrix sizes. The runtime are GPU benchmarks on both Nvidia change the performance or the run-time, could be used to find GTX 980 and Nvidia T4 systems. This information creates a foundation upon which NLP-based models can find correlations the absolute optimal combination of parameters for any given between source-code features and optimal choice of thread block configuration. Unfortunately creating such a dataset would, as sizes. mentioned above, take incredibly long time, and the amount There are several results that can be drawn out of our LS-CAT of data required would make the dataset huge. -

COMMUNICATION STUDIES 20223: Communication Theory TR 11:00-12:20 AM, Moudy South 320, Class #70959

This copy of Andrew Ledbetter’s syllabus for Communication Theory is posted on www.afirstlook.com, the resource website for A First Look at Communication Theory, for which he is one of the co-authors. COMMUNICATION STUDIES 20223: Communication Theory TR 11:00-12:20 AM, Moudy South 320, Class #70959 Syllabus Addendum, Fall Semester 2014 Instructor: Dr. Andrew Ledbetter Office: Moudy South 355 Office Phone: 817-257-4524 (terrible way to reach me) E-mail: [email protected] (best way to reach me) Twitter: @dr_ledbetter (also a good way to reach me more publicly) IM screen name (GoogleTalk): DrAndrewLedbetter (this works too) Office Hours: TR 10:00-10:50 AM & 12:30 PM-2:00 PM; W 11:00 AM-12:00 PM (but check with me first); other times by appointment. When possible, please e-mail me in advance of your desired meeting time. Course Text: Em Griffin, Andrew Ledbetter, & Glenn Sparks (2015), A First Look at Communication Theory (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Course Description From TCU’s course catalog: Applies communication theory and practice to a broad range of communication phenomena in intrapersonal, interpersonal and public communication settings. You are about to embark on an exciting adventure through the world of communication theory. In some sense, you already inhabit this “world”—you communicate every day, and you may even be very good at it. But, if you’re like me, sometimes you might find yourself wondering: Why did she say that? Why did I say that in response? What there something that I could have said that would have been better? How could I communicate better with my friends? My parents? At school? At work? If you’ve ever asked any of these questions—and it would be hard for me to believe that there is anyone who hasn’t!—then this course is for you! By the end of our time together, I hope you will come to a deeper, fuller understanding of the power and mystery of human communication. -

Introduction to Communication Theory ❖ ❖ ❖

01-Dainton.qxd 9/16/2004 12:26 PM Page 1 1 Introduction to Communication Theory ❖ ❖ ❖ recent advertisement for the AT&T cellular service has a bold A headline that asserts, “If only communication plans were as simple as communicating.” We respectfully disagree with their assess- ment. Cellular communication plans may indeed be intricate, but the process of communicating is infinitely more so. Unfortunately, much of popular culture tends to minimize the challenges associated with the communication process. We all do it, all of the time. Yet one need only peruse the content of talk shows, classified ads, advice columns, and organizational performance reviews to recognize that communication skill can make or break an individual’s personal and professional lives. Companies want to hire and promote people with excellent communi- cation skills. Divorces occur because spouses believe that they “no longer communicate.” Communication is perceived as a magical elixir, one that can ensure a happy long-term relationship and can guarantee organizational success. Clearly, popular culture holds paradoxical views about communication: It is easy to do yet powerful in its effects, simultaneously simple and magical. 1 01-Dainton.qxd 9/16/2004 12:26 PM Page 2 2 APPLYING COMMUNICATION THEORY FOR PROFESSIONAL LIFE The reality is even more complex. “Good” communication means different things to different people in different situations. Accordingly, simply adopting a set of particular skills is not going to guarantee success. Those who are genuinely good communicators are those who under- stand the underlying principles behind communication and are able to enact, appropriately and effectively, particular communication skills as the situation warrants. -

91 Communication Option Kits

PowerFlex 7-Class and AFE Options Communication Option Kits Used with PowerFlex Drive Description Cat. No. 70 753/755 AFE BACnet/IP Option Module 20-750-BNETIP ✓ BACnet® MS/TP RS485 Communication Adapter 20-COMM-B ✓✓ Coaxial ControlNet™ Option Module 20-750-CNETC ✓ ControlNet™ Communication Adapter (Coax) 20-COMM-C ✓✓ (1) ✓ DeviceNet™ Option Module 20-750-DNET ✓ DeviceNet™ Communication Adapter 20-COMM-D ✓✓ (1) ✓ Dual-port EtherNet/IP Option Module 20-750-ENETR ✓ EtherNet/IP™ Communication Adapter 20-COMM-E ✓✓ (1) ✓ Dual-port EtherNet/IP™ Communication Adapter 20-COMM-ER ✓✓ HVAC Communication Adapter 20-COMM-H ✓✓ (1) ✓ CANopen® Communication Adapter 20-COMM-K ✓✓ (1) ✓ LonWorks® Communication Adapter 20-COMM-L ✓✓ (1) ✓ Modbus/TCP Communication Adapter 20-COMM-M ✓✓ (1) ✓ Profi bus DPV1 Option Module 20-750-PBUS ✓ Single-port Profi net I/O Option Module 20-750-PNET ✓ Dual-port Profi net I/O Option Module 20-750-PNET2P ✓ PROFIBUS™ DP Communication Adapter 20-COMM-P ✓✓ (1) ✓ ControlNet™ Communication Adapter (Fiber) 20-COMM-Q ✓✓ (1) ✓ Remote I/O Communication Adapter (2) 20-COMM-R ✓✓ (1) ✓ RS485 DF1 Communication Adapter 20-COMM-S ✓✓ (1) ✓ External Communications Kit Power Supply 20-XCOMM-AC-PS1 ✓✓✓ DPI External Communications Kit 20-XCOMM-DC-BASE ✓✓✓ External DPI I/O Option Board(3) 20-XCOMM-IO-OPT1 ✓✓✓ Compact I/O Module (3 Channel) 1769-SM1 ✓✓✓ (1) Requires a Communication Carrier Card (20-750-20COMM or 20-750-20COMM-F1). Refer to PowerFlex 750-Series Legacy Communication Compatibility for details. (2) This item has Silver Series status. (3) For use only with DPI External Communications Kits 20-XCOMM-DC-BASE. -

Media Influence: Communication Theories

MEDIA INFLUENCE: COMMUNICATION THEORIES Hypodermic Needle Agenda Setting Reinforcement Theory Uses & Gratification Encoding/Decoding Theory Function Theory Theory YEAR 1920 - 1940 1972 1960 1974 1980 THEORIST Various Maxwell McCombs Joseph Klapper Jay Blumler Stuart Hall Donald Shaw Elihu Katz OVERVIEW A linear communication theory This theory suggests that the Klapper argued that the The Uses and Gratification Stuart Hall’s which suggests that the media media can’t tell you what to media has little power to Theory looks at how people Encoding/Decoding Theory has a direct and powerful think but it can tell you what influence people and it just use the media to gratify a suggests that audience influence on audiences, like being to think about. Through a reinforces our pre-existing range of needs – including derive their own meaning injected with a hypodermic process of selection, omission attitudes and beliefs, which the need for information, from media texts. These needle. and framing, the media have been developed by personal identity, meanings can be focuses public discussion on more powerful social integration, social dominant, negotiated or particular issues. institutions like families, interaction and oppositional. schools and religion entertainment. organisations. AUDIENCE Audiences are passive and Audiences are active but, Audiences are active and Audiences are active and Audiences are active in homogenous, this theory does not when it comes to making exist in a society where they can have power over the decoding media account for individual differences. important decisions like who are influenced by important media. If people don’t messages. They can to vote for, they draw on social institutions. -

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D. POOLEY Muhlenberg College, USA Communication theory, like the communication discipline itself, has a long history but a short past. “Communication” as an organized, self-conscious discipline dates to the 1950s in its earliest, US-based incarnation (though cognate fields like the German Zeitungswissenschaft (newspaper science) began decades earlier). The US field’s first readers and textbooks make frequent and weighty reference to “communication theory”—intellectual putty for a would-be discipline that was, at the time, a collage of media-related work from the existing social sciences. Soon the “communication theory” phrase was claimed by US speech and rhetoric scholars too, who in the 1960s started using the same disciplinary label (“communication”) as the social scientists across campus. “Communication theory” was already, in the organized field’s infancy, an unruly subject. By the time Wilbur Schramm (1954) mapped out the theory domain of the new dis- cipline he was trying to forge, however, other traditions had long grappled with the same fundamental questions—notably the entwined, millennia-old “fields” of philos- ophy, religion, and rhetoric (Peters, 1999). Even if mid-century US communication scholars imagined themselves as breaking with the past—and even if “communica- tion theory” is an anachronistic label for, say, Plato’s Phaedrus—no account of thinking about communication could honor the postwar discipline’s borders. Even those half- forgotten fields dismembered in the Western university’s late 19th-century discipline- building project (Philology, for example, or Political Economy)haddevelopedtheir own bodies of thought on the key communication questions. The same is true for the mainline disciplines—the ones we take as unquestionably legitimate,thoughmostwereformedjustafewdecadesbeforeSchramm’smarch through US journalism schools. -

Information Theory and Communication - Tibor Nemetz

PROBABILITY AND STATISTICS – Vol. II - Information Theory and Communication - Tibor Nemetz INFORMATION THEORY AND COMMUNICATION Tibor Nemetz Rényi Mathematical Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary Keywords: Shannon theory, alphabet, capacity, (transmission) channel, channel coding, cryptology, data processing, data compression, digital signature, discrete memoryless source, entropy, error-correcting codes, error-detecting codes, fidelity criterion, hashing, Internet, measures of information, memoryless channel, modulation, multi-user communication, multi-port systems, networks, noise, public key cryptography, quantization, rate-distortion theory, redundancy, reliable communication, (information) source, source coding, (information) transmission, white Gaussian noise. Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. The Origins 1.2. Shannon Theory 1.3. Future in Present 2. Information source 3. Source coding 3.1. Uniquely Decodable Codes 3.2. Entropy 3.3. Source Coding with Small Decoding Error Probability 3.4. Universal Codes 3.5. Facsimile Coding 3.6. Electronic Correspondence 4. Measures of information 5. Transmission channel 5.1. Classification of Channels 5.2. The Noisy Channel Coding Problem 5.3. Error Detecting and Correcting Codes 6. The practice of classical telecommunication 6.1. Analog-to-Digital Conversion 6.2. Quantization 6.3 ModulationUNESCO – EOLSS 6.4. Multiplexing 6.5. Multiple Access 7. Mobile communicationSAMPLE CHAPTERS 8. Cryptology 8.1. Classical Cryptography 8.1.1 Simple Substitution 8.1.2. Transposition 8.1.3. Polyalphabetic Methods 8.1.4. One Time Pad 8.1.5. DES: Data Encryption Standard. AES: Advanced Encryption Standard 8.1.6. Vocoders 8.2. Public Key Cryptography ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) PROBABILITY AND STATISTICS – Vol. II - Information Theory and Communication - Tibor Nemetz 8.2.1. -

Poolcomm Setup Wireless Capability with Water Quality Controllers

Poolcomm Setup Wireless Capability with Water Quality Controllers Contents Registration. .............................. .2 Cell/Satellite. ......................... .2 WIFI. .................................... .3 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS Basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: Failure to fol- low instructions can cause severe injury and/or death. This is the safety-alert symbol. When you see this symbol on your equipment or in this manual, look for one of the following signal words and be alert to the potential for personal injury. WARNING warns about hazards that could cause serious personal injury, death or ma- jor property damage and if ignored presents a potential hazard. CAUTION warns about hazards that will or can cause minor or moderate personal injury and/or property damage and if ignored presents a potential hazard. It can also make con- sumers aware of actions that are unpredictable and unsafe. Hayward Commercial Pool Products 10101 Molecular Drive, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20850 www.haywardcommercialpool.com USE ONLY HAYWARD GENUINE REPLACEMENT PARTS To activate your new CAT 4000 wireless controller on the Poolcomm web site you must first create an account. Register PoolComm Account Go to www.poolcomm.com, and select the “Register Account” link on the top left of the page. Complete all the required company information and press “Register”. You will receive an email containing your 8- letter login in password. This can be changed to a password of your choice after your first login. Register New Unit Once logged in, select the “Register New Unit” tab. Next using the six digit serial number printed on the side of the controller, fill in all the information and then select “Register Unit”. -

RESPONDING to COMPLEXITY a Case Study on the Use of “Developmental Evaluation for Managing Adaptively”

RESPONDING TO COMPLEXITY A Case Study on the Use of “Developmental Evaluation for Managing Adaptively” A Master’s Capstone in partial fulfillment of the Master of Education in International Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Spring 2017 Kayla Boisvert Candidate to Master of Education in International Education University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, Massachusetts May 10, 2017 Abstract Over the past 15 years, the international development field has increasingly emphasized the need to improve aid effectiveness. While there have been many gains as a result of this emphasis, many critique the mechanisms that have emerged to enhance aid effectiveness, particularly claiming that they inappropriately force adherence to predefined plans and hold programs accountable for activities and outputs, not outcomes. However, with growing acceptance of the complexity of development challenges, different ways to design, manage, and evaluate projects are beginning to take hold that better reflect this reality. Many development practitioners explain that Developmental Evaluation (DE) and Adaptive Management (AM) offer alternatives to traditional management and monitoring and evaluation approaches that are better suited to address complex challenges. Both DE and AM are approaches for rapidly and systematically collecting data for the purpose of adapting projects in the face of complexity. There are many advocates for the use of DE and AM in complex development contexts, as well as some case studies on how these approaches are being applied. This study aims to build on existing literature that provides examples of how DE and AM are being customized to address complex development challenges by describing and analyzing how one non-governmental organization, Catalytic Communities (CatComm), working in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, uses DE for Managing Adaptively, a term we have used to name their approach to management and evaluation.